Karl Burkheimer

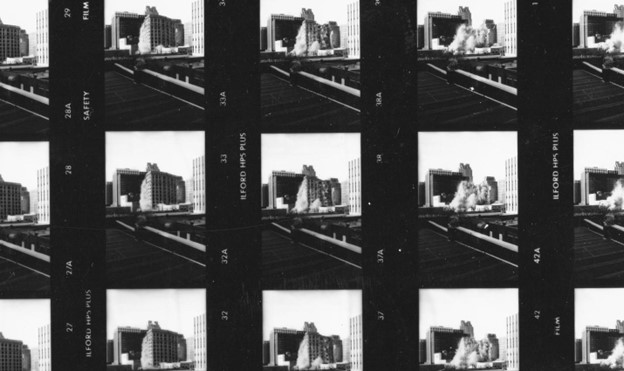

On a spring morning in 1991 I set up my tripod and attached a well-worn secondhand Nikon fitted with a borrowed motor drive and telephoto lens. Thanks to a friend of a friend, I was well situated to witness the impending destruction of the Commercial Bank Building. Despite the building’s historic significance and acknowledged architectural charm, its 80-year tenure as a fixture in a small Southern city was ending. Its removal was deemed essential for progress.

That morning I was among thousands of bystanders scattered across various vantage points awaiting the spectacle. Though I had recently finished my undergraduate degree in architecture, I was only vaguely aware of the controversy surrounding the building’s demolition. While I lacked a developed understanding of the cultural fabric of my city, I did recognize that the event, a first for the city, was functioning as an effective sleight of hand, deflecting social critique of the impending erasure with the promise of carnival-like entertainment. Nevertheless, from my perch I simply wanted to exercise a creative impulse to suspend time with images of twisted and contorted materials of a failing structure.

At 7:30am an unwanted edifice of commerce—including the steel, concrete, terra-cotta, limestone, marble, brass, wood, glass, plaster, and paint that composed it—slid through my viewfinder into a cloud of dust. The proposed 24 story bank headquarters slated to replace the Commercial Bank Building was not built, resulting in a 15-year hole in the urban plan. The 36 images I took that morning yielded seven uninteresting strips of black and white film that were eventually relegated to a cardboard box on the top shelf of a closet.

The inevitable failing of structures and systems that signify human existence should cause little surprise. The conceit of established constructs is constantly besieged by ever-changing conditions, rendering committed outcomes to temporal incarnation of past notions—regardless of the motivations or aspirations associated with these endeavors. Building, marking, developing, installing, maintaining, mending, documenting, replacing, erasing, and destroying only provide illusions of control. Yet, from this futility arises the instinct to create. The perpetual conditions of imperfection and impermanence incite the insatiable desire to dream, to aspire, to commit, to affect. Undoing becomes a necessary component of—if not the impetus for—doing.

This issue of Drain is built on the oblique gaze, peeking behind the surface to reveal glimpses into the alternative or the obfuscated. Abigail Susik begins the (un)built with, D.E. May and the Gift of Unknowable Intimacy. Susik explores the elusive entanglement of artist and place, locating an opacity within the everyday as a point of access into the inexhaustible legacy of May’s art. Gabriela Jauregui’s succinct poem, Sharpen’er Eras’er, concludes this issue of Drain by surrounding emptiness with crisp ambiguities, allowing the ‘page’ to bind and separate. Absences and adjacencies form connective threads throughout the issue, and the ‘spaces’ between each of the submissions build a meaning and structure wholly unique to each reader.

In between Susik’s and Jauregui’s bookends lies a diverse set of experiences, expressions, and endeavors, with recurring themes of process, place, and perception. Through the lens of Sisyphus’s plight Adam Forrester’s essay, Up and Down and Back Again: (un)doing Our Relationship with Success and Failure, confronts the complex cycle of creation and destruction. Anne Bujold’s interview of Travis Townsend further illuminates a perpetual process through Townsend’s practice founded on continually re-working materials and form. Shara Chwaliszewski’s interview with Chris Chandler emphasizes the insertion of rupture into the creative process as a provocation to excite outcomes. Ryan Riss’s unbuilding of a drawing shares the rejection of absolutes, refusing to let outcomes sit idle as stagnant completions. The conflict between resolved and unresolved also permeates Helen T. Abbot’s composition, Basorexia: A Rumination on Unrequited Love.

Kate Te Ao’s Te Waimapihi | Te Aro Park Memorial, Brian Libby’s 100 Runs, A Pedestal and Transformation, and Steph Littlebird’s Reframing Monuments from an Indigenous Perspective are poignant reflections on the politics of place. Each essay insightfully unbuilds complicated histories of erasure and inequality, while providing thoughtful insight into processes and projects working to reclaim and mend. Clipping-out Inside Arcadia: Reflections on a Quarantine Gothic, Malcolm Doidge’s thought experiment, employs a digital anomaly in virtual reality, ‘clipping,’ to expound on place and conditions of isolation. Unreliable Landscapes by David Cowlard exploits the capricious and untrustworthy metadata of geographical navigation via the failings of ubiquitous web mapping platforms. Jeff Carter’s Psychosomatic Texture Maps and Floorplan Stickers also engages the limitations of web mapping as a foundation of his exploration of the Singer Pavilion, a remnant of Michael Reese Hospital campus in Chicago, yet the digital investigation is re-converted into tactile interventions.

Heidi Schwegler’s Single Use meditates on the sculpted wind-blown polystyrene packing material she collects from the Mojave Desert and utilizes in her practice. Hannah Newman’s work, Pangea: A Multimedia Epoch, weaves geology, technology, and language, generating oddly familiar yet other-worldly forms. The process-based installations of Richard Maloy’s Cardboard Constructions ‘grow’ over time filling their environments, thus affecting change and becoming complicit with their architectural surroundings. Though different in scope and focus from Maloy’s work, Gupi Ranganathan’s trans-form: a study for liminal meanderings shares a similar strategy of unbuilding through subsuming the gallery structure over time with dedicated attentiveness.

The Woman, Examined by Kara McMullen deconstructs narrative through the instability of story within shifting perspectives. Similarly, Thamizh Futurism by Adhavan Sundaramurthy takes control of narrative, interrupting clichéd determinations of traditional art, particularly in response to de-colonization. Marissa Lee Benedict and David Rueter’s BLANK, UNBLANK further challenges narrative while simultaneously requiring a deeper focus from readers to navigate ‘missing’ information. Gabriela Jauregui uses storytelling as a tool of interrupting established understandings in Ahora: La Isla, an excerpt from her first novel Feral.

Squeak Meisel engages the unbuilt through his on-going project of surveying artist sketchbooks. He provides excerpts from three interviews, providing candid insight into how creative structures and systems develop and how they are interrupted. Similarly, Avantika Bawa and Vishwa Shroff demonstrate an ease in their discussion while on a walk. They navigate their familiarity and inquiry into each other’s practice with the interviewer and interviewee casually shifting as the discussion develops. Informality is an opening into the unbuilt, a refusal to mitigate situations and conditions through generalities and simplicities or rules and restrictions. Something as simple as a walk and a discussion becomes an impetus for recalibrating and reconfiguring the rigid ideas, schemes, and methods.

Through the process of working on the (un)built I have come to consider unbuilding far more common than building. After all, those 36 images I took 30 years ago were useless until I wrote this essay.

Karl Burkheimer is an artist and educator with diverse experiences across a spectrum of creative disciplines, methodologies, rationale, and outcomes. Focused on a haptic and tactile understanding of the environment paired with a human need to creatively express, his work is a commitment to practice manifested as investigations of craft. His work has been exhibited nationally, including solo exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles. And, he has received several awards of recognition as well as institutional funding, including an Individual Artist Fellowship, Oregon Arts Commission; a Project Grant, Oregon Arts Commission; the 2013 Contemporary Northwest Art Awards at the Portland Art Museum; 2013 U.S.-Japan Creative Artist Fellowship; and the 2016 Ford Family Fellowship in Visual Art. In 2019 he co-founded Rainmaker Craft Initiative, a non-profit educational platform committed to creative inquiry founded on Craft.