Kate Te Ao

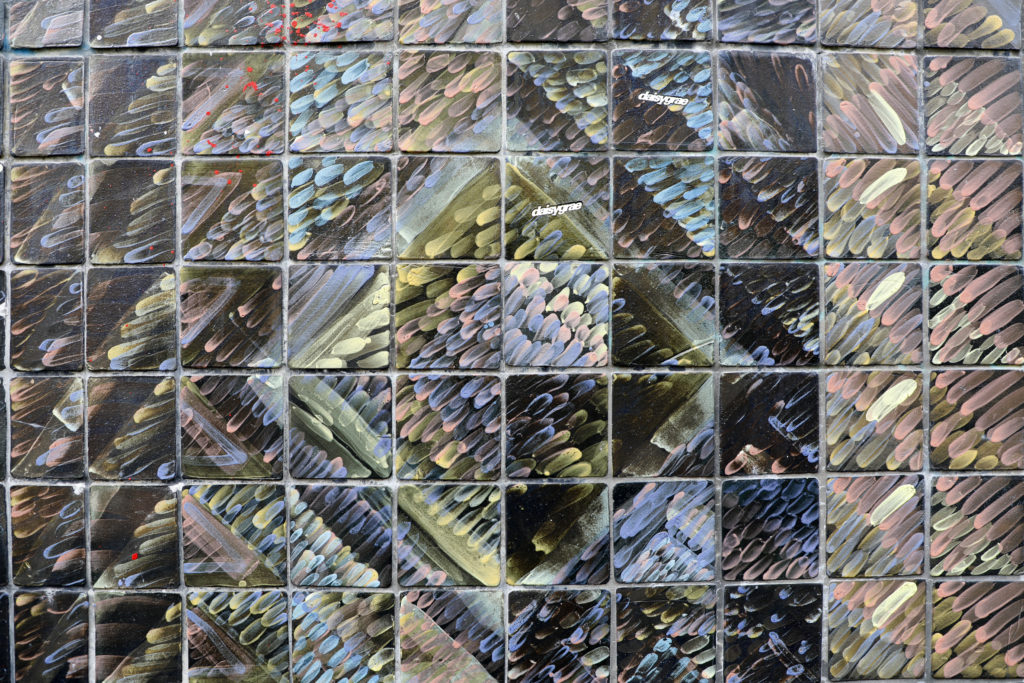

All images from author’s personal archive, Te Waimapihi, Wellington, 2022.

Te Waimapihi is a waka. The prow rises up and pushes against the pavement. Courtney Place, rushing to meet it, divides in two and flows past on either side.

Courtenay Place becomes Manners Street on the port side of the waka.

Manners Street follows the curve of what was once the shoreline. Te Aro pā stood on that shoreline. When my ancestors arrived, becoming Pākehā as they stepped ashore, they built around and eventually over Te Aro pā. The people of the pā left and my ancestors continued. Stealing land and building over it.

Te Waimapihi asks us to remember.

Remember the people who lived here. Remember the plants that grew. Remember the stream that flowed down Aro valley to the sea.

I forgot, I never knew.

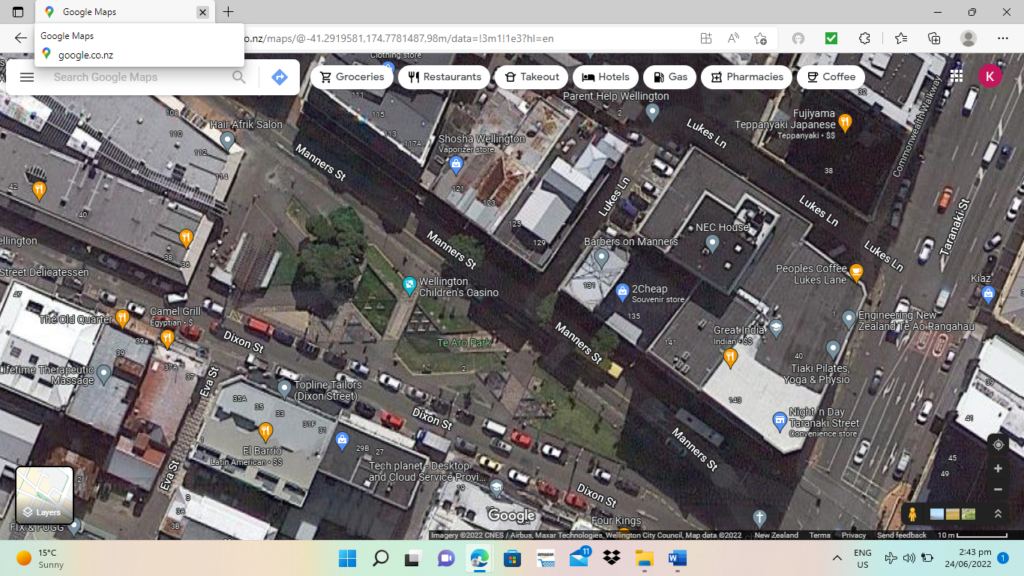

Google Maps, Te Aro Park/Te Waimapihi, Wellington, accessed June 2022.

If you’ve ever been to Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington, the capital city of Aotearoa/New Zealand, you have probably walked through Te Waimapihi/Te Aro Park. This small slice of land sits at the intersection of Courtenay Place and Taranaki Street, between the strip club Dreamgirls and the public toilets. It is frequented by flocks of raucous seagulls, sometimes flocks of raucous drunks. Considered equally unsavory by the general public, these visitors add an air of neglect to the park.

Living here, you have the sense of one narrative, language, and landscape being slapped on top of another. Tidy grids of streets with names like Churchill Avenue have been placed on vertiginous hillsides. Streams have disappeared into pipes to flow silently under the streets. The rivers are strangers. But there are significant gaps, breaks and slippages in what Pākehā ecologist Geoff Park termed ‘the language of invasion’.[1] Through her work, Te Waimapihi, Shona Rapira Davies has created one of these breaks, piercing the fabric of the city to acknowledge the history of the land.

Shona Rapira Davies was commissioned to create Te Waimapihi by Wellington City Council in the late 1980’s. A Māori woman of Ngāti Wai ki Aotea descent, Rapira Davies began the project in 1988, just five years out of art school. Dogged by budget blowouts and public backlash, the project caused so much controversy that passersby stopped to abuse Rapira Davies as she laid some of the 30,000 handmade ceramic tiles that make up the work.[2] The work Rapira Davies created is an acute triangle shape, the narrowest point marked by a tall, curved form that represents the prow of a waka. Tiled paths, benches, and ponds repeat the triangular form.

Te Waimapihi/Te Aro Park is an example of an artwork firmly rooted in the history of a place while also creating a new space in which one can be present. Prior to the arrival of British settlers and the establishment of the new capital city Wellington, Te Waimapihi was the site of a Māori settlement. A stream ran down the valley to the shoreline on which the settlement was built. The city was built around and eventually over the settlement and the people who lived there were forced to leave. The stream was diverted into a culvert. Te Waimapihi uses a series of triangular ponds to reincarnate the stream. The work invites you to sit with the sound of the water and run your hands over the imprints of leaves, their trees long gone. Rapira Davies provides a model for the way in which an artwork can acknowledge the past while complicating and enriching the present. The strip club, the public toilets, the air of neglect, the long-departed pā, and the shoreline pushed back into the sea. The park embraces the entanglement of our histories with the present. It is not a memorial of the war variety; it does not demand your solemn contemplation. While Rapira Davies’ had no way of knowing how the streets around her work would be changed and developed, the fact that her work is firmly rooted in the history of the land means that Te Waimapihi remains untroubled by the toilets and the traffic.

Geoff Park describes Te Waimapihi as “an exquisite ecological expression of place, a wild almanac of locality in which we can see what is lost when a place is defined with the words of invasion”.[3] Park’s essay, in which he discusses Te Waimapihi, draws together the colonial history of Wellington with the ecosystems, flora, and fauna of the place. He acknowledges the need for a sense of place in these “sudden cities” and suggests that an understanding and clarification of the locally distinctive, the “genius loci”, is the way in which we might find this.[4] This genius loci can be found in Te Waimapihi through the tiles that bear the imprint of leaves and seaweed and those that list names of significant ancestors. Te Waimapihi also shifts our experience of landscape, American essayist Rebecca Solnit describes as “not just a place to picnic but a place we live and die”.[5] People do indeed sit in the park to picnic, but Rapira Davies’ acknowledgment of the history of the land and original inhabitants undoes any notion that this small slice of land is neutral. It was indeed a place people lived and died long before it became a place people sat to drink coffee in takeaway cups.

The park falls into the category of art-making that Solnit describes as conversational, interacting with subject and site in a conversational give-and-take, “assuming meaning is to be found rather than imposed”.[6]

Using the form of the waka as a metaphor for both vessel and journey, distance and time, Rapira Davies opens up a space in which multiplicity and entanglement are both encompassed and embodied. Rather than having a didactic, educational aim, the work has a more subtle and subversive purpose. It places our current experience in conversation with the past. The waka carries the stories of the pā and its people into the noise of the city. The air of neglect that surrounds the memorial resonates with some of the broader societal responses to both the importance of art and artists and the importance of acknowledging our colonial history. Ignorance, willful or otherwise, negligence and the marginalization of Māori remain highly visible in that space.

A quiet challenge, a slippery space. Te Waimapihi is an act of remembrance, reclamation and complication.

[1] Park, Geoff. Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006), 45.

[2] Meekings-Stewart, Pamela. “A Cat Among the Pigeons,” 1992, Television Documentary, 41:48, https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/a-cat-among-the-pigeons-1992.

[3] Park. Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua, 45.

[4] Park. Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua, 46 – 52.

[5] Solnit, Rebecca. As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender and Art (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001), 12.

[6] Solnit, As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender and Art, 5.

Kate Te Ao is an artist who lives and works in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa. She has recently completed her Master of Fine Arts through Toi Rauwharangi College of Creative Arts, Massey University.