Steph Littlebird

You can learn a lot from the objects a culture leaves behind. This concept is the basis for the entire discipline of Art History. Examining cultural products can give us a greater understanding of any group of people or for the collapse of empires, the rise of Fascism, and the emergence of social change. Art, design, and day-to-day objects are like the fingerprints of culture and reveal their underlying values and beliefs.

According to Merriam-Webster, a monument is “lasting evidence, a reminder, or example of someone or something notable or great.” But who decides what’s “great”? Monument building is practiced by cultures the world over. From the Washington Monument in D.C. to the Pyramids of Giza, humans like to erect objects that will last for generations. Sometimes they’re meant to honor someone in government or a spiritual leader, and sometimes, they commemorate events or ideas—i.e., the Statue of Liberty representing freedom.

But what do we do with expired memorials that have soured over time? How do we interact with monuments of people like Christopher Columbus or Robert E. Lee? Some viewers interpret these statues as a blatant celebration of racism and genocide. And for many communities, the removal of such contentious monuments can become an opportunity for healing, forging new networks, and collectivization.

Many contemporary artists have grappled with how to design intentional and holistic monuments. Arguably the most notable is Maya Lin, best known for designing the Washington D.C. Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Lin has worked on many public and private environmentally driven memorials. Her works are distinctly modern in aesthetic but with an eye toward the ecological.

Maya Lin, Bird Blind at Sandy Delta Confluence Park, 2008. Photo by U.S. Forest Service – Pacific Northwest Region, courtesy Wiki Commons.

Lin’s work with the Pacific Northwest-based Confluence Project is a series of public artworks spanning 430+ miles of the Columbia River, following the path of Lewis and Clark’s famed expedition. Lin is said to have only agreed to helm the multi-site project after Tribal leaders agreed to play a significant role in the planning process. This multi-state collaboration was heavily guided by input from local Tribes, including the Chinook, Umatilla, and Nez Perce.

During the project, Lin wrestled with how to “remember” the historic American explorers and their legacy related to the Doctrine of Discovery and the myth of “Manifest Destiny.” The artist felt it was important to include the voices of Tribal people who were present on the land before and after the time of the historic expedition—those voices which are often excluded from historical recollection. During the design and construction phase of the project, Lin consulted with Indigenous elders and leaders from across multiple Indigenous nations to create thoughtful monuments that were remarkably considerate of the land.

One of the Confluence sites is located at Sacajawea State Park in the Tri-Cities area of Washington State. The park is located at the convergence of the Columbia and Snake Rivers; Lewis and Clark first traversed this area in October 1805. This area is also a long-established gathering place for local Indigenous peoples. Part of Lin’s memorial design included an installation called the story circles. These large concrete circles are embossed with Indigenous words and the history of the land. This park and the intersection of the two rivers represent the collision of cultures and how colonization continues to affect us today.

Besides Lin’s physical installations, she also invested project funds into restoring the park’s shoreline. Not only did the artist create a physical monument, she also repaired some of the damage created post-Oregon Trail.

With the current resurgence of Indigenous discourse might not seem so radical, but the Confluence Project began in 2002. Just 20 years ago, Native voices were not regarded as “authoritative,” particularly within the academic institutions of history, ecology, or fine art. Lin’s inclusion of Indigenous voices in planning these anti-monuments directly opposes the traditional approach to American remembrance, which erases marginalized groups.

Maya Lin, Second view from Vancouver Land Bridge with regional Indigenous motifs and petroglyphs, Washington, 2020. Photo by Another Believer, courtesy Wiki Commons.

While the physical monuments Lin designed in collaboration with Tribes are quite beautiful, Lin and the legacy of the Confluence Project have grown far beyond those physical memorials. The Confluence in the Classroom program is an example of how those static monuments became a catalyst for social change. Now each year, this program enables Pacific Northwest students and teachers to engage with Native educators and creatives. In the program, participants learn about Indigenous systems of knowledge and grow their understanding of local Native life directly from the source.

Over two decades, the program has generated more impact on communities through programming than any monument, frankly, ever could. By investing in public programming and community enrichment opportunities, monuments can become a place for learning and discourse. This supplement to the monuments imbues the objects with more significance because of what the Confluence programming has actually done to advance Indigenous voices and enrich surrounding communities.

One thing that’s always bugged me about the practice of monument building is (at least in American history) has not always been considerate of the landscape. Take Mount Rushmore, for example; an area considered sacred to the Lakota tribe, defaced to commemorate white men. Not only was the mountain permanently disfigured, but the lands were also seized (after treaties were signed) when the U.S. government realized there was gold in the Black Hills. (Not to mention, the history of mining throughout the west is fraught with ecological disasters and irreparable damage to the landscape. See California’s Yuba Gold Fields).

Maya Lin, Entrance to Vancouver Land Bridge over the Lewis and Clark Highway in Washington, 2013. Photo by Visitor7, courtesy Wiki Commons.

It’s easy to spot patterns when you examine America’s tendency to memorialize predominantly white males. Rarely do we see statues of notable people of color, women, or disabled folks. Even more rarely do we see monuments to the land. The concept of “honoring” land is foreign to many people outside of Indigenous cultures. Most tribal societies revolve around Earth’s cycles, and those subtle patterns quietly dictate our lives during the year.

As part of Portland’s Monuments and Memorials Project during the 2021 CONVERGE 45 festival, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Oregon (CTGR) were invited to participate in the exhibition Prototypes. CTGR is comprised of over 30 different bands and tribes from across Oregon. All Indigenous peoples of the area (known as Portland today), including the Clackamas, Cascades, Multnomah, and Tualatin Kalapuya, are part of the confederation that is the Grand Ronde Tribes today. The Grand Ronde reservation is located west of Portland, between McMinnville and Lincoln City.

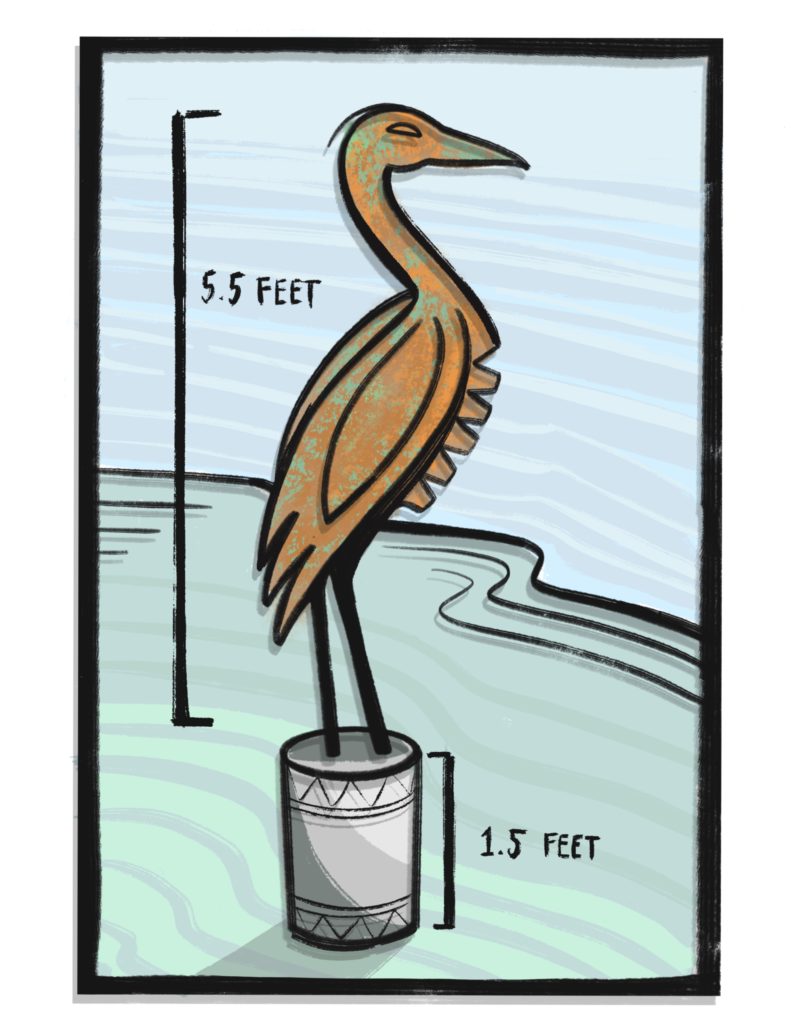

This group show asked participants from diverse backgrounds to propose monuments for “our current time and place” and to rethink a monument’s role within a community. In response to this prompt, CTGR proposed a temporal monument that is adaptive to seasonal changes and continues an ancient tradition of the local Clackamas Tribe. The Clackamas are one of the first peoples of the land we now call Portland. The First Fish Herons proposal is based on a yearly tradition of the Clackamas Tribe, where heron statues are carved from wood and placed along the Willamette River to watch for the first spring Salmon.

The concept submitted by CTGR includes inviting artists from the community (both Native and non-Native) to create new heron sculptures each year, similar to the Clackamas tradition. By opening this tradition up to the community in a Tribe-sanctioned way, people could connect to local Indigenous people’s stories, art, and teachings respectfully and authentically. Through this process, CTGR proposed to create a safe place for the public to learn about the history of the land, the river, and the Indigenous people of that place.

Steph Littlebird, Detail of CTGR Heron concept, 2022.

As we collectively reflect on the purpose and meaning of monuments in our communities, it’s important to consider future generations. It’s also important to understand that community values based in place are likely to have more relevance to current and future generations.

As municipal and federal institutions dole out money each year for public art, they should think more broadly about community values and not just mirror their own. Creating inclusive monuments with purpose should be the goal. While monuments can serve as nationalistic propaganda, their impact could be much more, given the right approach, monuments can be universally accessible.

Consulting marginalized groups about monuments in their communities is a way to begin healing the wounds of American imperialism. Instead of erecting symbols that alienate community members, we should be creating art that is inspirational and aspirational. By making space for those who have been historically excluded from telling their own stories, creating monuments that reflect more diverse values can impact the long-term importance of a cultural artifact to the generations who come after.

Disclaimer: While I was a member of the collaborative group that brought this proposal to life, the ideas and opinions expressed in this article are solely mine and do not reflect the opinions of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

Steph Littlebird is an artist, curator, writer, and a registered member of Oregon’s Grand Ronde Confederated Tribes. She received national recognition as curator of This IS Kalapuyan Land (2020) an exhibition at the Five Oaks Museum in Portland, which was featured by ArtNews and PBS NewsHour. Littlebird is the 2020-2021 Fellow of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A widely published writer, she is currently writing a series about Indigenous Resilience for Oregon Arts Watch Magazine with the support of the Oregon Cultural Trust. As an artist, Littlebird’s work combines traditional aesthetics with contemporary materials and subject matter to forge connections between our collective past and imminent future.

Littlebird earned her B.F.A. in Painting and Printmaking from the Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA) in Portland, she currently lives and works in Las Vegas.