Malcolm Doidge

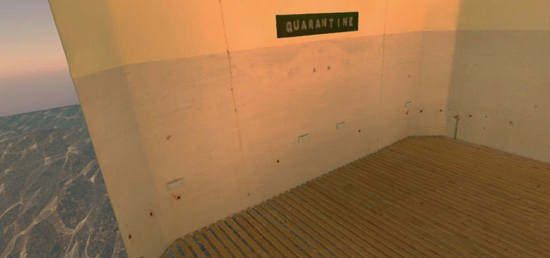

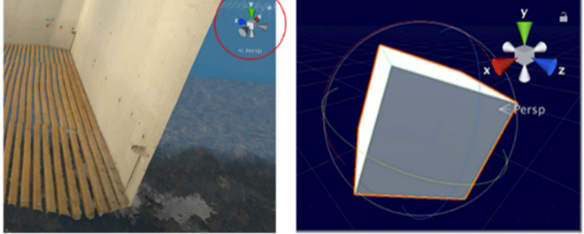

(fig.1) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia: The Vestibule, 2022, photogrammetry 3D model and clipping plane. Image courtesy the artist.

“Cutting off the outer edges or boundaries of a word, signal or image.” (n.d)

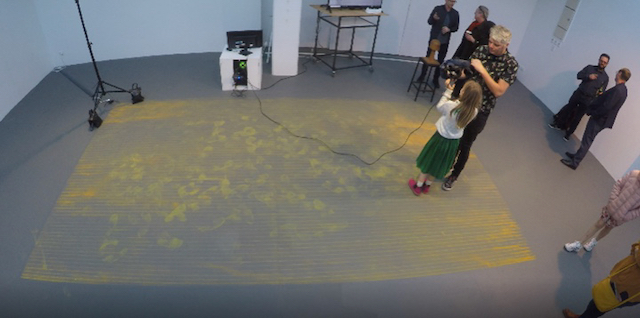

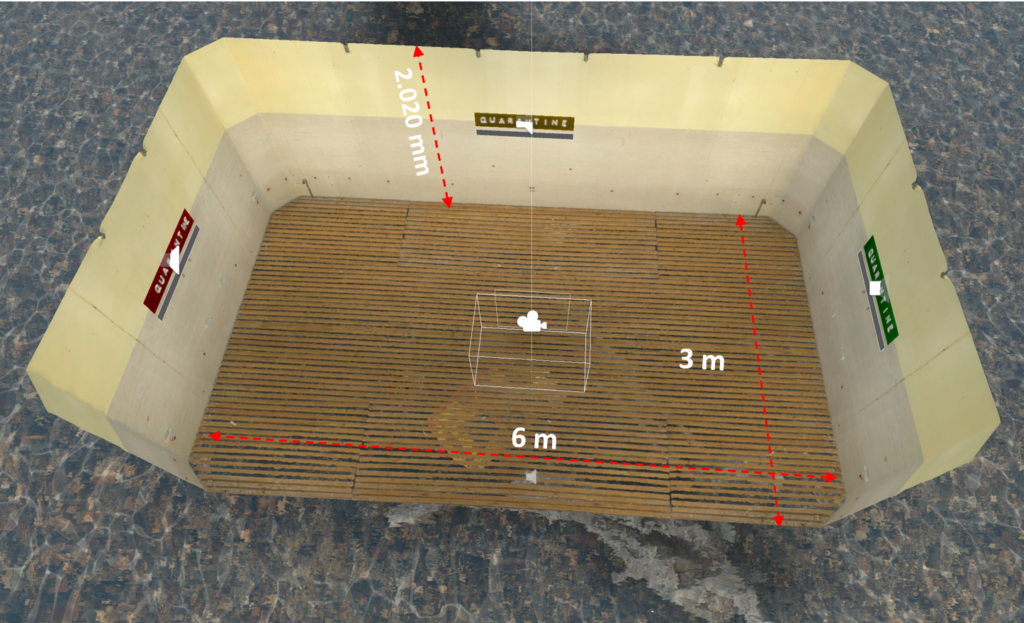

For gamers—anyone wearing an immersive, virtual reality headset (HMD) — ‘clipping’ virtual objects occurs leaning headfirst into VR digital scenography, then suddenly, going through it. Clipping-out is a motif for this thought experiment—the ghostly experience wearing a VR headset—being a virtual avatar walking through virtual walls. To borrow from Karl Marx, ‘all that is solid melts into air’ (Marx & Engels, 1848) when penetrating a near clipping plane revealing a world hidden behind digital scenography (fig.1). I’ll expand on this motif throughout this thought piece. Disclosure: I’m not a game designer. My interests combine sculptural installation, performance design and digital scenography. I discuss these in relation to my installation of Inside Arcadia (2020-21), an immersive VR experience wearing a Vive head mounted display (HMD) nested within a 6 x 3 metre yellow chalked floor installation (fig. 2, left). Putting on the HMD, the viewer is immersed in a digital scenography – the Vestibule – a model scanned from an animal quarantine pen (fig. 2, right), its virtual floor area matches that of the installation chalk floor together forming a virtual departing point for three other digital scenographies.

(fig. 2) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia: The Vestibule, 2022, Left. 6 x 3 m chalked floor Opening night 5th August 2021, video still. Right, The vestibule 3D model. Its area corresponds with the 6 x 3 metre chalked floor. Image courtesy the artist.

To make these four digital scenographies, I scanned historic quarantine and defence interiors using photogrammetry. This digital technique takes hundreds of photographs recombined within dedicated software to make a 3D digital model, a digital simulacra of a real place. That digital copy is combined with 360˚ audio field recordings, 360˚ timelapse videos, all within an immersive, virtual reality (IVR) game engine, a virtual space in which game designers utilise these same techniques for ‘world building’. World building, in game design, is about making virtual space productive for linear narratives, usually viewers or players becoming engrossed in achieving a set task in order to move to the next level. To aid this process, viewers are often immersed within a hyper-realistic digital scenography, the substitution of real space with its simulation in virtual space deploying an aesthetic focus promoting the illusion of ‘being there’. My thought experiment flips this application of digital hyperrealism with a provocation about world (un)building—virtual realities hyperreal bias reinterpreted as a phantasmagoria—where Inside Arcadia’s public exhibition revives ghosts of a quarantine past. The digital phantasmagoria I refer to is a quarantine gothic, my immersive virtual ‘tour’ of four VR digital scenographies experienced standing on the yellow chalk floor installation. My digital scenography is a mash up of site-specific photogrammetry scans, 360˚ media field recordings of historic human and animal quarantine—plus defence sites—made from Mātiu/Somes Island locations (fig. 3). This is a place of ecological and historic conservation near Aotearoa/New Zealand’s capital, Wellington, located inside its deep harbour, Port Nicholson/Te Whānganui-a-Tara. Over 150 years since British colonisation confiscated Mātiu for a quarantine island, Mātiu/Somes Island has been returned to its indigenous owners, the Māori tribal collective Taranaki Whānui ki te Upoko ō te Ika a Maui in 2009 as part of cultural redress, Te Hokitanga Mai ā Mātiu (The Return of Mātiu).

Inside Arcadia references this historic context by reflecting on the zoonotic[1] origin of the recent Covid-19 pandemic, especially given the Islands historic quarantine role, one establishing the economic domination—in the present—of early settler pastoral farming that ecologically devastated a landmass equivalent in area to the British Isles. Despite indigenous Māori already occupying the land for over 700 years, this transformation was promoted by an enlightenment conceit promoting New Zealand as a pastoral arcadia, a trope heralding of a ‘New Britain’ in the South Pacific. This 19th century colonising conceit sponsored mass European migration accompanied by disease, devastating Māori resistance, alongside land wars and indigenous dispossession. Although Mātiu/Somes Island was confiscated for human quarantine mid-19th century, colonisations pastoral legacy was strengthened in the 20th century when, a modern Maximum Security Animal Quarantine Station was built by the Crown in 1968.

(fig. 3) Malcolm Doidge, Mātiu/Somes Island, 2020, Panorama of Human and animal quarantine sites looking south to Te wāhi o te ahi tipua (Historic heavy AA battery defence site). Image courtesy the artist.

In the decades after Te Hokitanga Mai ā Mātiu, Taranaki Whānui have generously encouraged creative, practice based research on the island – my own included. However, early 2020, the global Covid-19 pandemic emerged to furlough my post graduate study mid-point. Most people in Aotearoa/New Zealand—exempting essential services—followed a necessary government order to go into lockdown. Suddenly, the solid world of research and work disappeared with quarantine imposing a social, political, and academic form of ‘clipping-out’, albeit saving tens of thousands of lives in Aotearoa/New Zealand’s remote islands as the nation clipped-out on the rest of the world[2].

What then emerged—as borders closed—was an uncanny quarantine gothic: silent cities, empty skies and highways leading to eerie abandoned urban locales. Terry Castle, feminist author of The female barometer, wrote of the uncanny in Phantasmagoria: Spectral technology and the metaphorics of modern reverie noting that “ghosts did not exist but, one saw them anyway. Indeed, one could hardly escape them, for they were one’s own thoughts bizarrely externalised” (Castle, 1988, p. 58). She was referring to the 18th century pre Freudian invention of the uncanny via magic lantern technology (later Victorian stereoscopy), ghostly illusions projected for an incredulous, paying public. As Castle noted, the etymology of ‘phantasmagoria’ combined ‘phantasm’ or ghost with ‘agoria’, the latter derived from agoreuein (to speak in public). Together, they represented a mode of allégorie or allegory; ghostliness seen in public spaces (Castle, 1988, p. 237). Inside Arcadia appropriates Castles’ phantasmagoric genealogy for a quarantine gothic, the immersive VR experience replacing VR world building’s anodyne ‘play space’[3] with a chalked floor installation in art galleries.

(fig. 4) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia. Phantasmagoria: The bunker, 2022, HMD Screenshot, Image courtesy the artist.

Bizarrely externalised during lockdown was Mātiu/Somes essential Islandness—its isolation—a spectre of that past now returned in the present experienced as a quarantine gothic (fig. 4). Here Inside Arcadia’s site specificity rubs up against video gaming industries recreation of ancient sites,[4] a hyperreal aesthetic that—mediated by immersive VR—trades off ‘being there’ as a vicarious form of VR tourism, history plus the digital sublime. Ontological speculation aside concerning simulacra i.e., the copy replacing the original’s use value. Hyperreality can achieve a deception so convincing you forget you are physically somewhere else is a world building context that otherwise suppresses the metaphysics of presence by emphasising ‘flow state’, what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called a mental state of intense focus, one induced by game level design insisting that virtual space is also ‘productive’ space. This means forgetting-the-self when focused on tasks like collecting rewards, progressing to the next level, achieving progress. Clipping-out will mess with flow state by disrupting absorption in hyperrealisms visual illusionism. In VR, you simply do that sticking your head through something virtual appearing to be real. All that is solid melts into air, Marx and Engel—in this sentence—recognised artisan and craft worker traditions of the 19th century were being rapidly replaced by industrialised piecemeal work in factories. In 21st century game industries, immaterial Fordism (Schumacher, 2016) works at a transnational scale, tasks are atomised using contracted labour to make the AAA gaming product. Inside Arcadia’s World (un)building is, by contrast, artisan in its studio/cottage scale. My artisan speculation about world (un)building references these contemporary means of production in the context of artists, since 2016, appropriating from a burgeoning of affordable prosumer VR tools and gaming industry techniques while making virtual spaces as painters, sculptors and other creative workers to relocate their work to as VR/AR analogies, in parallel with erstwhile material outputs (Wallis & Ross, 2020).

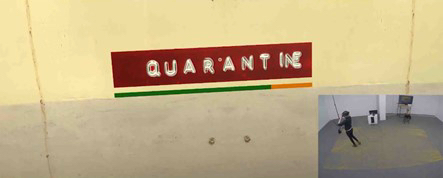

Inside Arcadia’s phantasmagoria of world (un)building rejects flow-state tasks with digital scenographies preplacing these as ‘view only’ scenes, meaning, no interaction is triggered by setting a hierarchy of tasks associated with the digital scenography. Each of Inside Arcadia’s scenes has a duration that times out using various scenographic devices, returning the viewer to the Vestibule hub that allows a viewer’s gaze—wearing the HMD—to then select another of three phantasmagoria. By looking at a ‘QUARANTINE’ ‘hotspot label’, the viewer activates a teleport to that scene and, after visiting all scenes, the experience resets in a different order (fig. 5).

(fig. 5) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia. The Vestibule, 2021, HMD screenshot of hotspot labelled QUARANTINE for teleporting. Inset, video still of viewer activating the hotspot. Image courtesy the artist.

Hyperrealism insists that its illusionism—within virtual space—simply relocates the space of the everyday to 3D realm of ‘virtual space’. Espen Aarseth, video gaming ontologist, wrote in Allegories of space that the ‘virtual space’ of computer games and their hyperreal scenographies are actually allegories of space, “they pretend to portray space in ever more realistic ways, but rely on their deviation from reality to make the illusion playable” (Aarseth, 1998, p. 169). For example, the disembodied illusion wearing the HMD is unachievable outside of immersive, virtual space. The game engine software and computer is a silent performance partner enabling point-of-view experience wearing of the HMD—the metaphysical ‘I am’ of Cartesian logic—to provide an illusion co-ordinated to align the physical body when immersed with the digital void organised as a grid. This is the side-to-side lateral X, the vertical Y, and the front-to-back sagittal Z together co-ordinate a zero point in the RGB (Red/Green/Blue) software void (Davis, 2012, p. 8) (fig. 6). Clipping-out on these RGB channels or signals subverts Cartesian illusionism therefore revealing a little of world building that is hidden.

(fig. 6) Malcolm Doidge, Perspective view of Cartesian space, 2021, GUI screenshot of game engine. Image courtesy the artist.

Aarseth also advocated for a ‘spatial turn’ concerning virtual space by referencing Henri Lefebvre’s The production of space (1991). For Lefebvre, space was socially constructed, thus shared, and argued virtual space is also socially constructed by way of allegory. Therefore, unlike a mathematical grid of Cartesian coordinates devoid of humanity, space is defined by human interactions, virtually, but within a material world. For Inside Arcadia and its VR quarantine gothic, this concept is illustrated with a crossover moment when viewers—wearing the HMD—are immersed in virtual space while contributing footprints, over the duration of the exhibition, to a 6 x 3 metre yellow chalk palimpsest (fig. 7). Allegory here—simply put—describes one thing by pointing to some other, related thing; the trace of ghosts we might imagine becoming externalised.

(fig. 7). Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia installation floor, 2021. Chalk footprints on gallery floor installation. Image courtesy the artist.

Speculating about immersive, virtual world (un)building, the chalk floor is the nexus linking Inside Arcadia’s virtual space with its material world, yellow being the international colour of the maritime quarantine flag flown by an infected ship entering harbour. This is where virtual space exhibits Mātiu/Somes Islands historic quarantine sites allegorically—the digital scenography is performed as part of a public exhibition by viewers—as footprints are material trace of the collective, the virtual and immersed social experience of a quarantine gothic. Wearing the HMD on the chalk floor installation is a performative action corresponding, particularly, to Phantasmagoria: The human quarantine barrack (fig. 8). The performative action of walking a virtual quarantine gothic that has been technologically spectralised as a phantasmagoria.

(fig. 8) Malcolm Doidge, Phantasmagoria: The human quarantine Barrack, 2021, HMD screenshot photogrammetry software 3D point cloud visualiser model in Unity scene with 360º timelapse video. Image courtesy the artist.

The photogrammetry model here was spectralised by a point cloud treatment[5] (fig, 8) including an immersive, 360˚ binaural audio mix seen and heard here: https://youtu.be/q8uah6bzZTw. This diaphanous expression of world (un)building presents a 360˚ environment that sparkles within a shroud of digital fog—a miasma—in turn hosted within a spherical panoramic shell. Into this sphere, a dawn-to-dusk 360˚ video timelapse is projected, fluttering through the scenography in a looping palimpsest, threading the scene (fig. 8, right). Augmenting this scenography is the recorded voice work of actor and singer Vanessa Stacey (Ngati Kuia/Te Āti awa), reading from a visual-poetry piece written by me for the 2017 ‘Performance, writing’ symposium held on the Island. Treated with an audio stutter mix and digital fuzz overlay, her recording includes some environment field recordings from the island. This audio builds over 170 seconds to the moment of the scenes abrupt cessation, two field recordings of metallic clanging briefly overshoot the fade-to-black finale, the rattling carcass of a colonial past. Each ‘view only’ phantasmagoria layers non-interactive 360˚ media combinations to resist video-game world-building by excluding its linear, hierarchical narratives e.g., completing a score of finished tasks to move to the next level. Another gesture towards world (un)building is included in Phantasmagoria: The animal quarantine boiler room (fig. 9).

(fig. 9) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia. Phantasmagoria: The animal quarantine boiler room 2022, HMD Screenshot. Image courtesy the artist.

This gesture is the scenes duration again treated performatively. That is, entering the scene, the ship’s chain animation ‘weighs anchor’, coinciding with the beginning and end of a single ambisonic or spatialised field recording (fig. 9). The animal quarantine boiler room is in the centre of the actual complex where the ambisonic mic is located. This recording captures me sprinting around the rooms perimeter, past all the animal pens, until exhausted. Running becomes a performative action determining the length of the scene, the only scene where the viewer, wearing the HMD with headphones, loses phenomenological reference—underfoot—to a virtual floor plane resulting in a ‘phantom subjective’ (Farocki, 2004 p. 17) experience, that of floating in virtual space. An important contribution to this scenes gothic atmosphere is a strong directional light, tracking in an infinity loop against the backdrop of another dawn to dusk 360˚ video timelapse. As if suspended mid-air, this glitching light and shadow play illuminates a chiaroscuro of scrambled textures mapped onto the boiler room models surface (fig. 10).

(fig. 10) Malcolm Doidge, Inside Arcadia. Phantasmagoria: The animal quarantine boiler room. 2022. HMD Screenshot. Image courtesy the artist.

The scenes world (un)building uses these scrambled 360˚ texture maps but, not as a Dadaist impulse toward 360˚ collage as non-sense making, more like collage as a virtual parataxical praxis. In other words, juxtaposition composed without offering connective tissue between visual features where, distorted photogrammetry models collaged with jumbled surface textures spatially nest within looping 360˚ timelapse video. My (Un)worlding approach here is a time based virtual palimpsest that, when exhibited as Inside Arcadia, includes a material trace of footprints deposited by viewers in chalk then erased over time.

One final digital scenography incorporating this theme of walking and trace is Phantasmagoria: The bunker (fig.11). I refer here to poet Hone Tuwhare (1922-2008) (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Korokoro, Ngāti Tautahi, Te Popote and Uri-o-Hau) and Papatūānuku (1975), his love poem to walking the earth – referencing Māori creation narratives of Papatūānuku the Earth mother separated from Ranginui, the sky father. With permission from the poets estate, Vanessa and I recorded Papatūānuku whereupon she recalled the warm timbre of her own father speaking of his ancestral tūrangawaewae (place-to-stand or home base). Tuwhare wrote Papatūānuku in response to a 1975 protest land march, Te Rōpū o te Matakite (Those with foresight) which he participated in while protesting indigenous land alienation – travelling the length of Aotearoa/New Zealand’s North Island – to the Capital, Wellington, and in Parliament grounds.

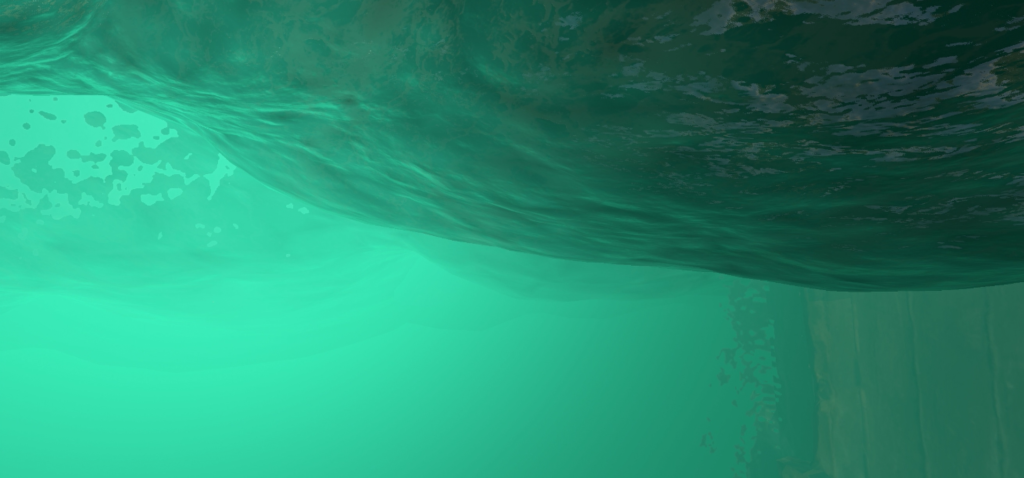

(fig. 11) Malcolm Doidge Inside Arcadia. Phantasmagoria: The bunker, 2021, chalk floor, HMD Screenshot of water shader wave. Image courtesy the artist.

Phantasmagoria: The bunker has an accelerated day/night cycle, speeding from dawn to dusk over 120 seconds signifying time is ‘out of joint’ and, for this scenographies duration, the viewer immersed wearing an HMD stands on a photogrammetry model of ammunition magazine interiors from Mātiu/Somes Island. Digital waves wash over the viewer on this scenographies floor level model that, in reality, is te wāhi o te ahi tipua, the historic WW2 anti-aircraft fortification near the Islands highest point (fig. 11). Some versions of Papatūānuku and Ranginui begin in darkness. Papatūānuku, the earth mother, rises from the water, light then enters the world when Papatūānuku is separated from Ranginui, at last—emerging from between them—their elemental children populate this world including Tangaroa, the sea, who emerges with a rising tide. Te Whanganui a Tara harbours Mātiu/Somes Island along with a strange vibration, an oscillation recorded by me and mixed with Vanessa’s reading of Papatūānuku. This is the ‘Wellington hum’, a low-frequency thrum noted for over half a century, an enigmatic signal that apparently emanates from deep in the Earth. When borders closed the outside world ‘clipped out’ along with background traffic noise, silence elevated the mysterious Wellington hum; inexplicable. Inside Arcadia emerged amidst the Covid-19 pandemic when quarantine temporarily curtailed normalcy. Clipping out also means to remove part of a frequency or barrier, a short circuit to a new horizon, like poking one’s head through the Vestibule wall boundary. My thought experiment for world (un)building, Inside Arcadia, is Phantasmagoria: A quarantine gothic—its allegories of quarantine confinement figuratively ‘clipping-out’ pre-pandemic borders—disrupting productivity including everyday ‘flow’ – momentarily opening a gap in which to stop, stand still and wonder. Wonder about ghosts of colonialism, about global pandemic, about global heating, about global sea level rise in a rebooted world unmaking the Holocene, a world continuing to unravel before our eyes.

[1] A disease transmitted from animals to humans through intermediary species, often a result of human pressure on wild spaces.

[2] I co-wrote a chapter New Faith in Fakes: Out-takes from a false scenography for ‘Urban Corporis X Unexpected – Special Issue’ in 2021, exploring this political decision, and its creative consequences, for Aotearoa/New Zealand in a lockdown of 5 million people in response to the SARS-CoV-2 until vaccines arrived. Access here https://eprints.qut.edu.au/207473/1/UCX_e_book.pdf.

[3] A ‘play space’ is a physical floor area (a living room) digitally demarcated for moving about in when first setting up the HMD for game play. In this space the computer to track the position of the HMD in relation to the immersive, virtual scenography.

[4] Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed and ancient Greece is an example.

[5] A point cloud is made when data points, forming the digital mesh of a model, are rendered instead as points in space. The plug in code used enlarged these points.

Bibliography

Aarseth, E. (1998). Allegories of space. The Question of Spatiality in Computer Games. In M. Eskelinen & R. Koskimaa (Eds.), Cybertext Yearbook 2000 (pp. 152-171): Jyväskylä: Research Centre for Contemporary Culture.

Castle, T. (1988). Phantasmagoria: Spectral technology and the metaphorics of modern reverie. Critical Enquiry, 15(1), 26-61.

Champion, E. (2019). Norburg-Schulz: Culture, presence and a sense of virtual place. In E. Champion (Ed.), The Phenomonology of real and virtual places Routledge studies in contemporary philosophy (pp. 144-163). New York, NY: Routledge.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. S. (1998). Optimal experience psychological studies of flow in consciousness. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge university press.

Davis, S. B. (2012). History on the Line: Time as Dimension. Design Issues:, 28(4), 4-17.

Dillon, S. (2013). The Palimpsest. Literature, Criticism, Theory. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury.

Farocki, H. (2004). Phantom image (B. Poole, Trans.). In (pp. 13-22). Retrieved from https://monoskop.org/File:Farocki_Harun_2004_Phantom_Images.pdf.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). Manifesto of the Communist Party Chapter I. Bourgeois and Proletarians. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm#:~:text=All%20that%20is%20solid%20melts,entire%20surface%20of%20the%20globe.

n.d. Clipping. In PCMag Encyclopedia: The Computer Language Co Inc.

Moore, M., & Doidge, M. (2021). New Faith in Fakes Out-takes from a false scenography. In M. M. Borlini & A. Califano (Eds.), Urban Corporis X Unexpected – Special Issue (1 ed., pp. 315-324). Conegliano, Italy: Antefirma Edizioni. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/207473/1/UCX_e_book.pdf.

Pettit, H. (2017). Mystery ‘hum’ that has baffled people around the world for decades is recorded in the ocean. NZHerald. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/mystery-hum-that-has-baffled-people-around-the-world-for-decades-is-recorded-in-the-ocean/YEE75VS6YJOZEAUOWEUVIH2M3Y/

Schumacher, L. (2016). Immaterial Fordism: the paradox of game industry labour.

Stallabras, J. (2021). Sublime calculations. New Left Review, 132.

Wallis, K., & Ross, M. (2020). Fourth VR: Indigenous virtual reality pratice. Convergence. The innternational journal of research into New Media Technologies, 21(2), 313-329. doi:10.1177/1354856520943083

Malcolm Doidge is an artist and educator with a background in sculpture and creative technologies and has exhibited widely. Recently he completed a PhD by creative practice, his research, Inside Arcadia: An immersive virtual phantasmagoria, is the basis for this thought piece.