Victoria Wynne-Jones

flesh of stone

her black gown

black McCahon

the door shut

on now

a white shawl

– Joanna Margaret Paul [1]

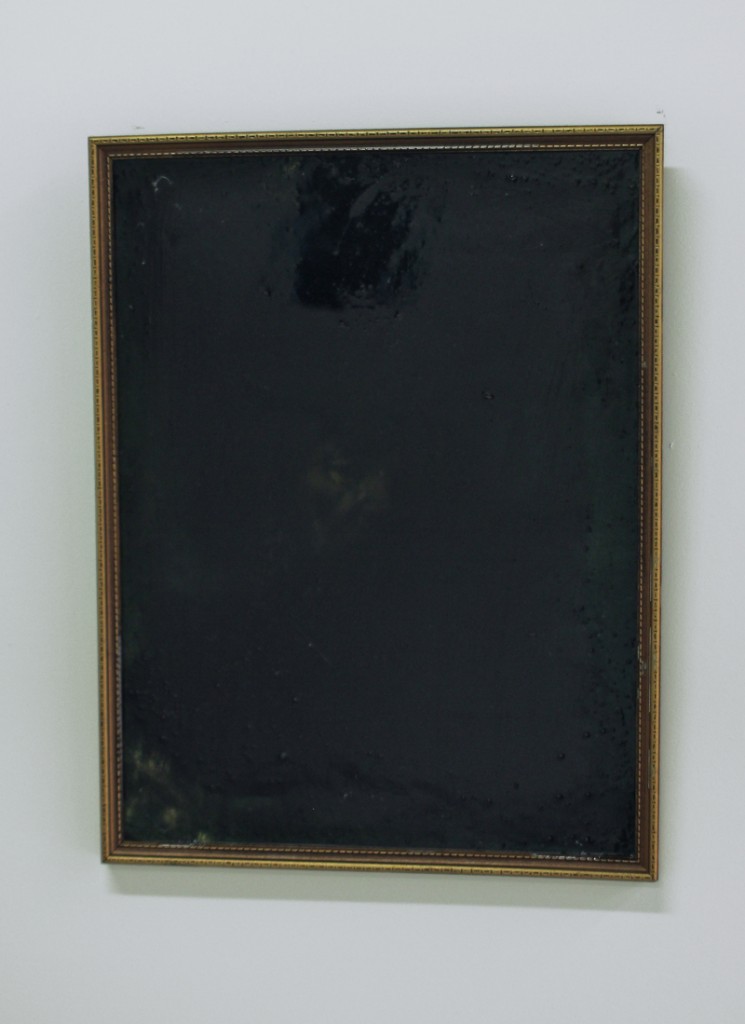

There is a black painting on a white wall. Its surface is slick and licked, quite oily in fact. It has a thin plastic frame that pretends to be ornate wood painted gold. On approaching one can see the peculiarity of this painted surface, it seems to have flowed upon its support, where it has then pooled and become still. The painting seems congealed, capturing the prior act of the application of a substance that has since dried and hardened in its own time. At first glance this is merely a black painting, however upon further inspection a face can be seen in its center, the face of a man.

The face in the center of the black painting is difficult to make out through the obscurity of its resin-coating. Upon squinting and tilting my head I came to a strange realization, the bulbous nose and tenebrous features seemed to signal that the visage had been painted by the Netherlandish old master Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). On reflection I realized that the image beneath the resin is actually a reproduction of Man with a Golden Helmet (c.1650) a work in the Gemäldergalerie of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. This painting, previously attributed to Rembrandt, was famously dis-attributed in 1985 and is now thought to have been painted by one of his students. Auckland artist Scott Satherley found a reproduction in a second-hand store and rehabilitated it into a new work, coating it with a black epoxy tint mixed in with resin. The result is a mysterious object, one that almost appears stained with years of blackened varnish, part apocryphal Rembrandt hidden in the attic, part sculptural assemblage.

Scott Satherley, Untitled, 2011, Resin on found object.

Satherley’s black painting was shown within a group exhibition entitled HOSANNA! in an empty commercial space within St Kevin’s Arcade on Karangahape Road in Auckland.[2] Commissioned by Alleluya bar and café, this exhibition sought to explore beneath the appeal for divine help that is hosanna, contemporary rituals of art-making that toy with various concepts of spirituality. Similar themes are prevalent throughout the history of modern New Zealand painting, with artists like Colin McCahon (1919-1987) and Ralph Hotere (b.1931) known for creating large-scale paintings, predominantly black with biblical references and Christian iconography. In contrast, the artists participating within HOSANNA! proffered a more earthy, ambiguous and sometimes multi-faith approach to this subject matter.

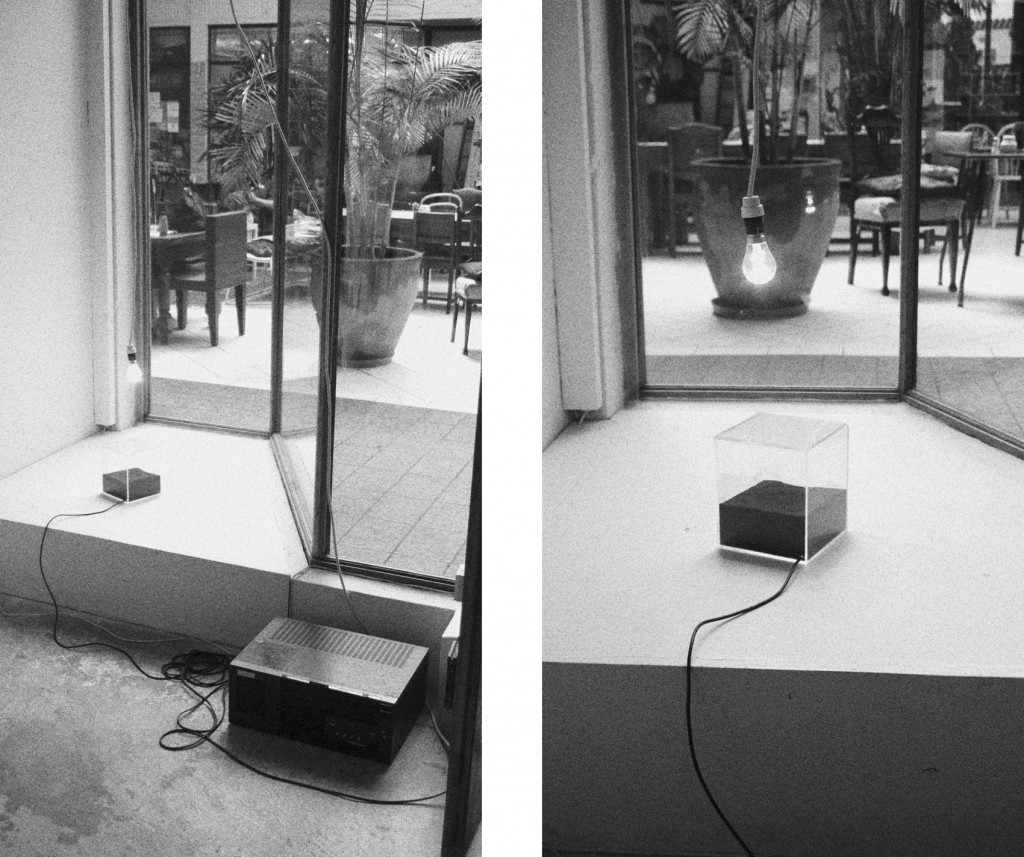

Originally Satherley intended to include another work in this exhibition, a large sheepskin stained in its center with a deep pool of black resin resembling blood, a twenty-first century peau de chagrin or golden fleece. Rather than hanging from an oak tree in the grove of Ares, the plan was for this fleece to sit on display within the shop window in St Kevin’s arcade. However the resin was not dry in time for the exhibition so Satherley included his black painting rather than the sodden fleece. Adjacent to his painting, placed in a nearby window is a work by Charlotte Drayton, a small Perspex box filled with black sand that has an illuminated light bulb suspended just above it. A re-occurring motif within black paintings since Pablo Picasso’s large-scale Guernica (1937), light-bulbs also frequently appear within McCahon’s oeuvre in paintings such as The Lamp in my Studio (1945, Auckland Art Gallery) and in works by another New Zealand painter, Philip Clairmont (1949-1984). In Clairmont’s Scarred Couch, the Auckland Experience (1978, Te Papa Tongarewa) a naked bulb swings above a battered sofa within a frenetic and multi-colored domestic interior. As in Guernica, a light-bulb within a darkened environment whether it be a holocaust, an artist’s studio or a crummy Auckland flat can sometimes symbolise enlightenment, awakening and hope. However it can also be a feeble and artificial light, one that merely serves to emphasise darkness, futility and despair with its inability to fully illuminate or triumph over its situation.

Charlotte Drayton, Untitled, 2011 Mixed media installation.

Drayton’s light-bulb is a kind of work-light, one that hangs unabashed from an extension cord that is visibly hooked onto the ceiling and then plugged into a neighboring socket. The light-bulb hovers over a box of magnetized black sand the artists harvested from the west coast beach of Karekare. Such iron-rich sand originates from volcanoes and is found on beaches on the West Coast of the North Island of New Zealand from Auckland to Whanganui. The sand is the stuff that both commercial mining operations as well as childhood trips to the beach are made of. Hidden within the box of sand is a speaker playing a slowed-down version of Elton John’s Blue Eyes (1982), a pop-ballad in minor keys. Gary Osborne’s dreamy lyrics intone

Baby’s got blue eyes

Like a deep blue sea

On a blue blue day…

Baby’s got blue eyes

When the morning comes

I’ll be far away…

Blue eyes

Holding back the tears

Holding back the pain…

Baby’s got blue eyes

And I am home

And I am home again.

Drayton’s work combines an artificial light, a sun-surrogate over beach-sand contained within a box and disrupted by the rhythms of Elton John’s wistful and virtuosic performance. Almost inaudible, his song is reduced to slow and fuzzy bass sounds that activate the black sand, displacing it and causing it to tremble. Within her installation Drayton deftly combines this sentimental adult-contemporary song with evocative materials via conventions of 1960s American Minimalism. Her use of Perspex alludes to the cubes of Hans Haacke (b.1936) and Dan Graham (b.1942) yet the clarity and crispness of the material is undermined somewhat by the extension cord that protrudes from it as well as its saccharine and distressed soundtrack.

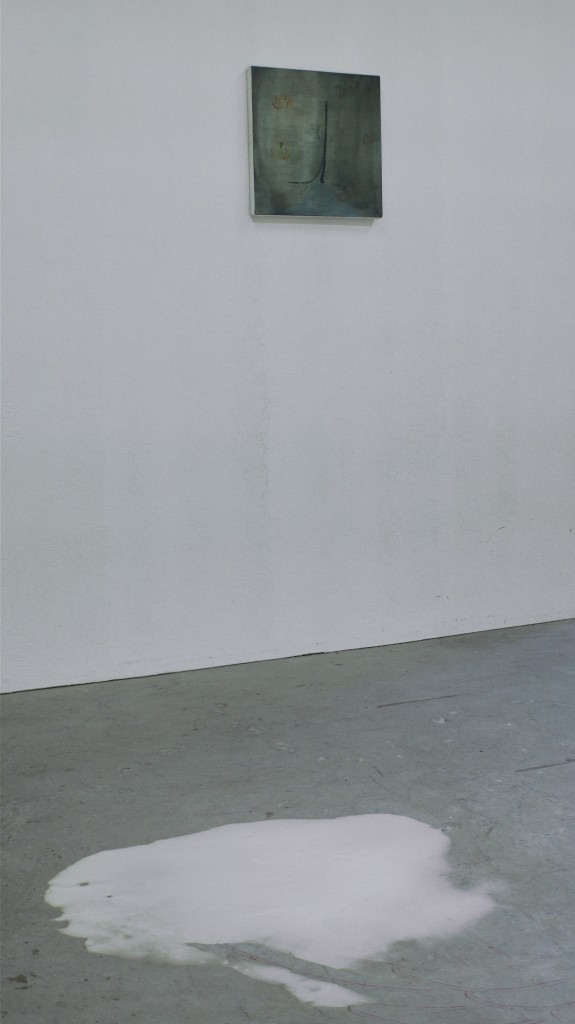

Campbell Patterson, Bathroom, 2011, Acrylic on canvas, Untitled, 2011, Liquid soap.

In the center, towards the back of the space, a painting by Campbell Patterson hangs on a wall that had been decorated by its previous inhabitants with shiny white floral wallpaper. Patterson’s painting is predominantly a faded and dirty sage green upon which stylised orange slices and dark green palm-like shapes have been painted. In the center of the painting is a calligraphic black mark, it almost resembles a cursive letter L or perhaps an aleph, yet it also appears as a mystifying and unknowable symbol. In light of the painting’s title Bathroom, the mark takes on a whole different meaning. On either side of the black painted mark, the dirty green background is slightly faded, and Patterson’s black mark becomes a division or cleft between two buttocks upon which are decorated fragrant and deodorising orange slices and partial tropical plants. Many of Patterson’s video works are secret performances he films in his bathroom and the sculptural objects he subsequently creates are vestiges of these performances often involving substances such as soap or materials like towelling cloth. In his video work Clean Jump (2007) Patterson jumps up and down wearing nothing but a blue towel until it falls off and in Three Attempts (2008) similarly clad, he climbs outside from one bathroom window, then clambers inside from a different one.[3]

Campbell Patterson, Bathroom, 2011, Acrylic on canvas (left), Untitled, 2011, Liquid soap (right).

In front of his painting, in the center of the floor, Patterson left a large white puddle of liquid soap and its sickly vanilla-coconut scent permeated the gallery. Upon the literally “low” and contaminated ground, this synthetic substance with its faux-natural flavors hinted at delusions of cleanliness and its large volume alluded to repetitive and obsessive acts of hand-washing, therapeutic attempts that are made to mask or eliminate the secretions of contagious bodies. The artificiality of certain scents that are thought to be clean brings to mind the work of another New Zealand artist, Dane Mitchell. Mitchell’s 2011 work shown at Artspace in Auckland The Smell of an Empty Space (Vaporised) involved a perfume slowly released into the gallery environment by an immaculate mirrored air pump unit. Designed by Mitchell in collaboration with the perfumer Michel Rounditska, the scent has a watermelon-like aftertaste. Containing synthetically produced ozone meant that it had a sharp, clean, fresh-air note that is often used in cleaning products to give the mistaken impression of cleanliness.[4]

The papered wall on which Patterson’s painting was hung previously functioned as the walls of two changing rooms complete with mirrors, coat hooks and black curtains. Within each of these cubicles were felted hats made by Xin Cheng. Suspended from invisible fishing line, each before a mirror and in a space that could be curtained off and made private, these hats without bodies took on a ghostly aspect. Both hats were made of naturally grey-colored Gotland sheep fleece, the process of felting involved laying out the carded fleece which at first looks like candy floss, sprinkling hot soapy water over the top, then lots of rubbing.[5] Once the fibers were reasonably tangled together, the form was then shaped on a block of sorts. One of the hats was inspired by those worn by Turkish whirling dervishes and the other one was based on a more generic hat form. However the edges of the latter went a big strange in the felting process and the result is a bowler-like hat that seems to be melting or disintegrating on one side, a transient shape that seems to be caught in the process of materializing. There is something haunting and indeterminate about these levitating hats, they are present, yet they hint at their absent owners. A strange indexicality is created, each hat seems to point to a certain absent being, one that is currently hatless.

Xin Cheng, Untitled, 2011, Felted wool and nylon wire.

Also on a wall, opposite Satherley’s black painting were three photographs by Daniel Strang. These photographs were taken with a digital camera and printed with a commercial printer onto blue-colored office paper. The black and white printing process meant that all the white parts of the high-contrast photographs in fact became reserves without ink revealing the blue paper support. In this novel approach to photographic print-making, shapes and images were formed from the presence and absence of black. The subject matter of these images is ambiguous, the first shows a stony wall from which mottled vegetation seems to tumble. On either side of these leaves are what seem like the traces of fingers clawing down the walls, perhaps incised or perhaps painted, recalling the traces of Ana Mendiata’s 1982 performance Body Tracks. Strang’s image seems to document either a desperate attempt to clamber and climb, a trace of falling or a dramatic finger painting. The second and central image is dominated by a large triangle painted upon a speckled surface. In the context of the exhibition premise this simple geometric shape might allude to the Holy Trinity, a New Age triangle, a delta or a Masonic eye of Providence on a stony background. The third image also depicts rocky surfaces and in the center of concrete surround is a cleft where grass or moss seems to grow, a vegetative wound within a rough surface.

Daniel Strang, Untitled, 2011, Ink jet prints on paper.

Here the currently ubiquitous medium of photography is taken to an extreme level of vernacular using the most accessible methods of production. Yet the results are subtle and disquieting and their subject-matter is unknowable. These photographs are suburban abstractions and they are uncanny in that they capture incised fragments of familiar surfaces such as concrete walls, asphalt roads and cement footpaths which are then altered and re-composed. Perspective has been re-configured until the elements within these images become strange and seem to possess alternative meanings. Aside from these ambiguous images constructed with the mundane technologies of office paper and commercial printing, Strang also created two more triangles in the exhibition space, one upon a wall and another upon a window. Each triangle was made up of the multi-colored tags that are used to hold bread bags closed. These square-like shapes were adhered to wall and window as support, repeating the potent geometric shape seen within his second image. Upon a wall are two diagonal lines that construct the shape, and on a window is a more solid, pyramid configuration.

Daniel Strang, Untitled, 2011, Plastic bread tags.

It is the re-occurring triangle that returns one to the original premise of the exhibition and each artist inflected it differently. It is an intriguing exercise to briefly re-examine each of the works in relation to the initial premise in tandem with concepts of black, the theme of this issue. Satherley’s painting uses black to create a viscous boundary, one that resembles the varnish of old oil paintings. His tinted resin seems to signify the mysterious obscurity within which historic art dwells, the murkiness through which we peer at centuries-old masterpieces. Here blackness is used, like age to give a cheap reproduction legitimacy and added value.

Drayton combines the somewhat invisible, banal and industrial elements of the lightbulb and extension cords with Minimalist-evoking Perspex and the emotive element of sand. The small collection of black-beach sand is a symbol of optimism and hope regardless of how feeble or misguided it might be, similar to the candles and lamps that appear in McCahon’s black paintings. Her inclusion of Blue Eyes tempers blackness and illumination with another color, the trite blueness of imagined eyes that are deep with pain yet marvelous to behold.

Patterson’s pseudo-primitive black character or painted mark it is the trace of a simple gesture, an up-stroke and a down stroke with a little ascension at the end. But as a mark its significance is unknowable, it seems to be a letter from a lost language. In light of the painting’s title, its grimy colors, the fruity shapes that surround the mark and the pallid circles that it separates, the mark can also be read as the division between buttocks and a hint of the dark orifice between them. In contrast, the pool of white coconut soap Patterson places upon the floor signifies a profane purity or cleanliness. In any discussion of black it seems inevitable that the matter of white is addressed as well and any discussion of whiteness alludes to the white cube of the art gallery space. Patterson’s whiteness points to the art gallery as a pure and neutral tabula rasa, yet this is also undermined by the sickly scent with which the so-called clean substance pervades the entire space.

The wool fibers that Cheng’s ghostly hats are crafted from combines black and white to make grey and with greyness comes indeterminacy and uncertainty. Cheng’s grey hats are suspended in space and caught in the act of apparating, as if photographed in black and white they are colorless. The comfort and warmth of woolen head coverings implies a familiar feeling of protection yet their flotation is other-worldly and supernatural. Here it is difficult not to be reminded of the sacredness or tapu nature of anything pertaining to the head in many Pacific cultures.

Descending from the highness and sacred nature of the head, Strang’s photographs look downwards and create two-dimensional images of incertitude from quotidian subject matter and common materials. The heaviness of photocopied black and its variability is used to make three images that capture aspects of literally earthly elements so that they appear to bear the traces of prior rituals of painting, or ancient growth processes. Black and the absence of black are used to create something from nothing, positive space from the absence of ink.

Similarly this exhibition briefly inhabited a commercial space that was temporarily empty between leases. For a spell, works by five artists toyed with notions of the sacred and profane, the contemporary and the historic, the pure and the impure. With such binary oppositions it is difficult to conceive of one member of each pair without its antithesis, just as in the extract by Joanna Margaret Paul at the start of this text demonstrates, the “black gown” and “black McCahon” are followed by the “white shawl.” Most importantly of all a wide range of materials were utilized including resin, sand, wool, soap, office paper, cheap printed reproductions, acrylic paints and bread tags. In light of the invocation of hosanna, that appeal for divine help, each artist used their materials to inflect and permute grandiose concepts of spirituality or blackness within particular and unique moments.

All images courtesy Daniel Strang

HOSANNA!

2-3 December 2011

Shop 18, St Kevin’s Arcade, Auckland, New Zealand

Xin Cheng, Charlotte Drayton, Campbell Patterson, Scott Satherley and Daniel Strang

(Curated by Georgina Watson and Victoria Wynne-Jones)

[1] Joanna Margaret Paul, like love poems. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006. P. 50.

[2] St Kevin’s Arcade was built in central Auckland during the 1920s. It runs between Myers Park and Karangahape Road, once the red-light district of Auckland, it is now home to scores of art galleries, boutiques, cafes, restaurants and night-clubs.

[3] Campbell Patterson Clean Jump, 2007 (digital video transferred to DVD, duration 1.51min) and Campbell Patterson Three Attempts, 2008 (digital video transferred to DVD, duration 6.55min). In 2011 Patterson also participated within the group exhibition The Bathroom Show at window, University of Auckland.

[4] Aaron Kreisler ‘Radiant Matter III / Artspace’ in Radiant Matter I / II / III / Dane Mitchell. Berlin: Berliner Künstlerprogramm/DAAD; Artspace: Dunedin Public Art Gallery: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2011. P. 66.

[5] See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QL5HbH_-LU4

Victoria Wynne-Jones recently completed a Master of Arts in Art History at the University of Auckland. Her research interests include contemporary art theory, curatorial practice and intersections between dance theory and art history.