Emmanuel Burdeau

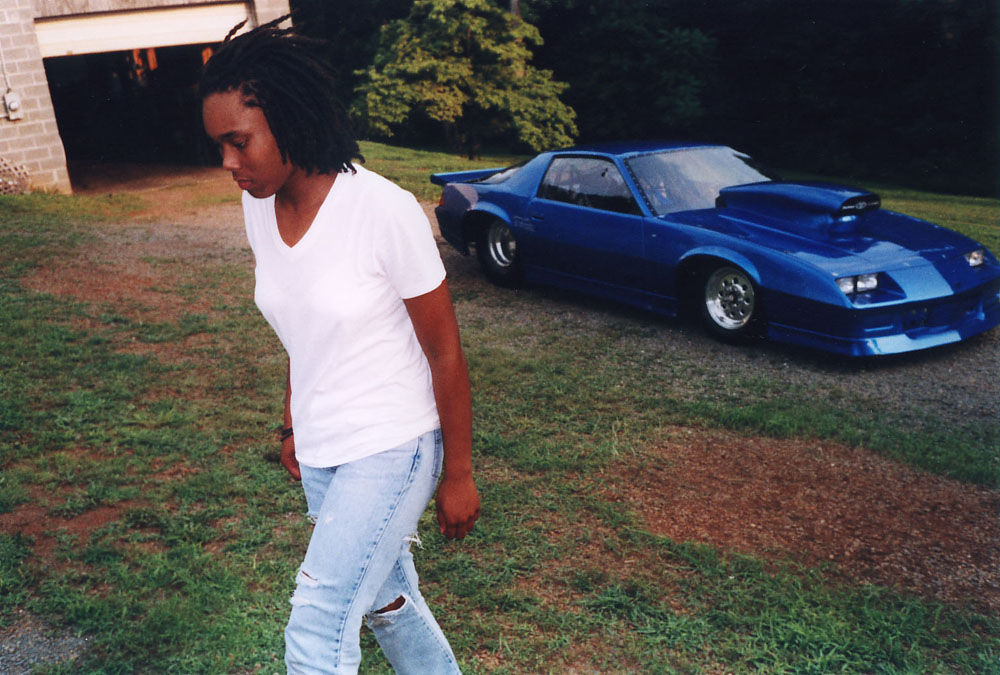

Film still from Company Line, 2009, 30:00, 16mm, mini-DV, B&W, color

©kje

What do we see in the films of Kevin Jerome Everson? We see what cinema rarely, if ever, shows. We see the ordinary gestures of America’s Black population, the gestures of work and sport, of the taxi driver, the trucker, the policeman, of the amateur and the champion. We see men and women talking to the filmmaker’s microphone or that of a TV station, going and coming with the rhythm of works and days, but also with the rhythm of images that originate as waves: flux and reflux, broad day and lights out, visibility and invisibility, etc. We see them inside-outside, on the porch of their home (Fifeville), alternating between two passions or two professions (Cinnamon, 72), or between vacation time and tasks that have to be performed before returning to work (Two-Week Vacation); in the incongruous interval between the numbers in a medical report and in newspaper discount coupons (140 Over 90); in the interval — unstable because of economic upheavals — between house and factory (Merger). We see them upside down, head above water now, now on the contrary seeming to be swallowed up by depths from which they will never emerge again. We see them driving, hands on the wheel, eyes fixed on the road ahead (Cinnamon, 72, Company Line…). We also see one with his head in the car-machine (Twenty Minutes, Undefeated), the other boxing and skipping in place to fight off the cold while his friend repairs, or tries to repair, the vehicle (Undefeated again).

Film still from Undefeated, 2008, 1:30, 16mm, B&W

©kje

We see them. We don’t see them. We see them again. We see them in 16mm, Super-8, Mini-DV, Hi-Def… We see them in color here, there in black and white, or alternating between them. We see the colors of the outside, of nature (Cinnamon, Blind Huber). Above all we see the shadows of the inside, of the factory (Lead, A Week in the Hole). There is not a single film by Kevin Jerome Everson that doesn’t return, at some point, to the black screen. This indicates the vast bedrock from which this cinema draws most of its images: America’s archives, televised or private. The documentary effect functions identically whether the found footage is real or simulated. The black screen is the abyss where this cinema catches its breath: an annihilation, but also a reservoir of images, the neutral gear through which every film passes before starting up again. The blackness alternates readily, and to marvelous effect, with the snow covering the lawns, the windshield and the roads (Merger, Company Line…). But just as the former is the blackness of the image, the latter evokes other granulations than the harsh winters of Ohio: the grain of images brought back from the past, souvenirs of the viewfinders of yesteryear, the pattering hail of an engine or a radio. Black and white aren’t just colors — they are also emissions, temporalities, depths of images. They speak of a temporal conjunction, the encounter between historical time (the History of America, the History of Black people in America, the History of how that people has been represented) and the time of what has been torn from that History.

So despite the riskiness of the rapprochement, how can we not think that the black screen has yet another, more general import? That it serves as a sign, and the absence of a sign, for Black people in America? Not because of an identity of color: that would be a little flip, and morally suspect. It’s something else — a relation to possibility, to what is, has been and could be. The return to blackness enacted by each film like a reflex, a reassuring gesture, a restorative pause, the resource that each film finds and keeps finding in the black screen, as its origin and perhaps its horizon — all that constitutes and sums up the way Kevin Jerome Everson looks at Blacks inside American History: a power that is at once flickering and continuous, immanent and ignored, manifest while escaping the ordinary rules of visibility.

What do we hear in the films of Kevin Jerome Everson? We hear the noise, the music of these waves. We hear a breath. Literally. Take the candles being blown out by the old man in Ninety-Three; the example is rich in something besides its theme: the man bending over the cake is illuminated only by the light of the candles, which also trembles, and now the whole 16mm format seems to imitate a breath. We hear that something is breathing, functioning, in the process of functioning, wishing to function. A rumor. A rumbling as discreet as it is insistent. It’s most often the sound of an engine, but the engine can just as easily be that of a vehicle — taxi, truck, 1984 super pro stock car …— as of a projector. It’s the noise of the work that this cinema has taken as its mission to document, and it’s also the noise of cinema at work. It’s the noise of the image itself, its pattering of hail, its showers, its snows, but its also the noise that real snow makes, real downpours, even storms. The hum of an engine is mixed up with the rattle of music: the opening credits of Cinnamon. The same hum is prolonged and becomes something else. The buzzing of bees, murmur of insects, the original soundtrack of adjoining fields: Blind Huber, and Cinnamon again. The noise of waves and birds is the aural equivalent of the slowing-down of the image, while the scratches add a few more birds to the sky: Aquarius. Appearances and disappearances, again. Goings and comings, this time between machines and nature, the nature of machines — cinema, the automobile, inventions of the Italian Renaissance — and the machines of nature, the insects from which the name of the production company for certain films by Kevin Jerome Everson was taken, Trich Arts.

Film still from Blind Huber, 2005, 16mm, 2:00, B&W, color, B&W

©kje

We hear. We no longer hear. We hear again. Just as each film passes through blackness again, each passes through silence again. Just as each film cuts the engine, each film cuts the sound. It’s hard to isolate the laws of these silences — some come as a surprise in the midst of a shot or a sentence. Like the black screen, they mainly have a respiratory function. They mark the places where the films turn back on themselves to take their own pulse. The sculptor that Kevin Jerome Everson is first and foremost expresses himself through these auditory operations, as he expresses himself through the manipulation of different formats, grains and weights of images. His depths are light, always airy, but they are depths, the addition of a visual and auditory third dimension.

How can we derive a meaning, perhaps even a politics, from the flickering of these sounds and images? The secret, if there is one, should lie somewhere between the extinction of a black screen and the roar of an engine — it’s hard to forget that the artist Kevin Jerome Everson is the son of a mechanic. Somewhere between the obstinately patient repetition of a single gesture and its suspension in silence no sooner than it has finally been accomplished. Here we are thinking of Cinnamon of course. In Cinnamon the bank employee and drag racer Erin Stewart confides that there are two kinds of driver: those who give it all they’ve got at the start, and those who give it all they’ve got at the finish. Like Erin, Everson clearly belongs to the first category: finishing, completing, going the distance, crowning don’t interest him. Starting does: starting, starting again, going back to the drawing board a hundred times, extracting a gesture or images from nothingness, drawing them out so that they are always on the point of returning. Drawing a form out of formlessness, preserving formlessness in form, is perhaps another characteristic of a sculptor…

Film still from Cinnamon, 2006, 70:00, 16mm, HD, B&W, color

©kje

Start what? Start. And hold on. One could say, thinking of the seas of Two-Week Vacation and Aquarius: float, keep your head above water. Or, thinking of the resurrected men in Playing Dead and Second and Lee: pull through, by the most discreet, the least visible means possible. A minute or seventy seconds, the length doesn’t matter: a tempo has to be initiated, a cadence. Hit your stride, to use a sports metaphor that many of these films suggest. Under the friendly, severe, paternal eye of the mechanic John Bowles, Erin spends the whole film looking for a good start. When she finds it, her blue racing car literally takes off toward the vanishing point and the sound is cut. The film will soon be over. The ignition, finally successful, has extinguished everything, by an operation that is like a gentle rewriting of the last seconds of Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop, where a similar screech of tires brings about a conflagration of the celluloid and with it the end of the film.

Everson can film boxing, baseball, car races… but competition isn’t what interests him. His eyes are not on the prize. If it happens that the hurrahs and applause of the crowd are heard in the background, it’s just so that we hear another breath, and no doubt with a certain irony, because these are the last seconds before the defeat of the home team that the camera documents by showing exclusively the scoreboard : Home. The chronometer records a countdown and not a record. The athleticism of numerous films of Everson, the athleticism that is complacently associated with Black Americans, is therefore no doubt a ruse. His cinema doesn’t have that conquering vitality, his images don’t have that facile positivity. They don’t pretend to substitute for other images, they don’t pretend they’re substituting one History for another. They slip into the absences of the winners’ History. The variety of lengths, the abundance of films — around fifty at this point — only trace a comedy of performance and excess. Everson is an artist who works in the interstices, a filmmaker who digs. A sculptor.

Film still from Ring, 2008, 1:30, 16mm, B&W

©kje

Intermittences, suspense, divisions. In keeping with a procedure that Everson likes to employ — dividing the screen into two frames that are slightly out of synch — the man who is aggressively and precisely throwing stones sees his gesture interrupted, his throw never to reach its goal: Ike. By the same procedure the attempt to winch up a damaged engine is put in relationship with the pulleys of another machine, drawn five centuries ago by Leonardo da Vinci: Twenty Minutes. The attempt to present the sweet science ‘in an elegant way’ turns boxers into dancers throwing slow-motion punches in the void: Ring. The family that can finally forget its weeks of labor by romping in the water is cruelly brought back, by means of superimposed titles inscribed on the image, to the tasks to be performed before the end of the stay, repainting the house, working on the roof….: Two-Week Vacation. Leisure time is also work, but in a way contrary to what is shown in Cinnamon.

And on the snowy highway in Undefeated, what is the force, or the lack of force, that circulates between the left and right side of the image, between this “boxer” skipping in place and boxing with the air, and this “mechanic,” his head in the engine? An invisible division is at work here. One can think of the two men as joined by a battery, a plus pole and a minus pole. One seems to be the other’s puppet. Who is repairing what? Who is repairing whom? The white flashes are perhaps more snow, another breakdown. Or perhaps they are sparks, the premises of a new departure. The image tries to stay in shape too. Is it therefore the champion, the real racing car? Circulations among machines, men, forms, again and always. Ironies of performance. Games of action and power, of power in reserve and power in action.

Film still from Second and Lee, 2008, 3:00, 16mm, B&W

©kje

The fables of two very short films, Playing Dead and Second and Lee, 1 minute 30 and 3 minutes respectively, are perceptibly similar. In Playing Dead a man tells a TV mike the ploy that enabled him to escape a shooting: he merely remained lying down without moving. In Second and Lee another Lazarus tells another story to the mike of yet another TV station: when the police ran toward him to arrest him, his reflex was not to move; if he had run, his flight would have given them a perfect excuse to kill him. How far we are from the mythologies of conquest and sport! The car is always there, but decidedly in neutral, au point mort. The exploit becomes the opposite of an exploit, heroism has only one formula: do nothing, lay low, play dead. Stay alive by feigning the interruption of life itself. Does this mean that passivity will be the Black’s victory, his salvation? Does intermittence ultimately give value to neutrality, passive resistance, survival by disappearing into the tapestry of the image?

Everson’s heroes are workers, proletarians. The emphasis is frequently on the difficulty of working conditions: Company Line, A Week in the Hole, Lead… Poverty is evoked, as well as the complex consequences of social and professional change: Fifeville, Merger… Racism is patent, but it is rarely directly evoked. We also have to pay special attention to the words spoken in Something Else. We’re in Virginia, the images date from the beginning of the 70s. A young woman who was just chosen Miss Black Roanoke speaks into the mike of yet another TV station. After asking her how she feels, the journalist questions her about the next phase, the election of Miss Black Virginia 1971. He wants to know if she thinks it would be a good idea to eliminate the segregation still in effect in such a competition. By asking this the man no doubts wishes to suggest that the young Black woman’s pride could be even greater if she won out over white competitors. But she sees things differently: beauty contests are one of the rare occasions where a black woman can feel “up,” so she thinks it’s preferable to maintain segregation.

This exchange is another fable, and this fable sums up the cinema of Everson. It speaks of victory and defeat. Of victory and defeat in the order of the visible; in everyone’s eyes and in one’s own eyes; inside a community and inside a country. Of victory and defeat in politics. She’s telling us that personal victory and defeat don’t necessarily apply to representation, or even — indeed much less — to emancipation. She’s telling us that they sometimes change places, become impossible to tell apart: to win a competition, you might have to withdraw from another… We are being told again that putting one image in place of another — a young Black woman on the throne of the nation’s beauties, for example — will never be an adequate solution or even a desirable one. Can we say, however, that Miss Black Roanoke’s message is Everson’s? Nothing indicates it with any certainty. Moreover, the message is not entirely clear: pride and humility play equal parts in it.

Film still from Something Else, 2007, 2:00, 16mm, color

©kje

We can nonetheless take a stab at a conclusion. If Everson has given himself the task of paying tribute to the ordinary lives of Black Americans, of documenting relentlessly what his producer Madeleine Molyneaux refers to as “the relentlessness of everyday life,” it is not to transform the defeated of History into victors of the Image by the miracle of cinema alone. Miss Roanoke triumphant on her float in the midst of yet another scintillation must remain ambiguous, possibly ironic, like the title, Something Else. What “something else” are we talking about? We have to come back one more time to intermittence. Its law can only be double: intermittent. On the one hand, Everson shows those that we never see, or see very little. He lights or re-lights a fire that has been seen badly. He makes a motor vroom that we don’t hear elsewhere. He produces or praises unperceived powers. But on the other hand, he never forgets that impotence is lodged in this power, a passivity in activity, a defeat in victory. In point of fact, that is always so, but it’s even more so here.

The constitution or reconstitution, the creation or re-creation of an archive, the invention of a representation for Black people in America should indeed not obliterate the actual place of this people; otherwise the film will fall into preaching, taking words for deeds, naïve belief in the powers of the image… This people must be shown differently, but it must also be shown as it is seen. It mustn’t be shown conquered. But it also mustn’t be shown victorious. One must put all the intervals of the world into play there: infinitesimal, infinite. Intermittences of blackness. Intermittences of power and act, of real and virtual, of politics and art. Let’s sum it up in one word taken from a film that has already been mentioned, one of the most beautiful among the twenty gathered in this collection. In Everson’s cinema, Black people are neither victors nor defeated. Neither defeated, undone nor recomposed. They are and remain undefeated.

English translation: Bill Krohn

Emmanuel Burdeau is a film critic based in Paris. He currently contributes articles to magazines such as Le Magazine, Litteraire, Trafic and Vacarme. He is also the editor of a series of books at Editions Capricci (Paris) that focuses on translations of American authors (J. Hoberman, M. Pomerance, S. Brakhage, S. Zizek, J. Agee, et al). He recently published two books of interviews for Capricci: on Werner Herzog (in collaboration with Herve Aubron) and Luc Mollet (in collaboration with Jean Narboni). Burdeau was the editor of Cahiers du Cinema from 2004 to 2009.

This essay was originally commissioned for the Video Data Bank publication/box set Broad Daylight and Other Times: Selected Works of Kevin Jerome Everson. Thanks to Emmanuel Burdeau and Brigid Reagan Balcom. For more information, please visit www.vdb.org

All images and clips courtesy of the artist; Trilobite-Arts- DAC and Picture Palace Pictures