Lindsey French and Willy Smart

Cautionary Signage in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. 7 January 2016.

Water becomes more saline as it approaches the Salton Sea. It is a lake with no outlet and no input either, other than what is diverted into the lake inadvertently or slyly advertently from irrigation waters. After our visit to the lake sea, we skim Google search results for ‘salton sea,’ ‘salton sea salinity,’ ‘salton sea salinity agriculture,’ ‘agricultural runoff salinity’ and so on. I cannot understand where the salt has come from—whether a residue of industrial agriculture or a more ancient residue of sea floors. Salinity is insidious. The example sentence the dictionary provides for “insidious” concerns sexually transmitted diseases: they too proceed in gradual, subtle ways, and result in harmful effects.

As the sea evaporates, its influence becomes atmospheric. I dream about a sleep hotel: a spa with all its facilities devoted to indulgent environments and technologies for repose. After the Salton Sea evaporates some years from now, clouds of dust and a rotten egg smell will kick off the dried lake floor and travel to nearby cities and resort towns.[1] Closer to the flat, a kind of grass grows out of the salt bloom. I lie on that queer grass. Tired, not exhausted. But tiredness can generate new genres as well—not the genres of limit-pushing but of easy sleep and itinerant attraction. There is no need here to ride into full depletion nor to be always on.

Waterfall Water (non-saline), 36ml. Hellhole Canyon, Anza-Borrego Desert, Borrego Springs. Received 7 January 2016.

As the reservoir becomes more saline from the particulates carried by currents of agriculture and water reapportioning agreements laid out in 2003,[2] it becomes uninhabitable to birds and fish and unsavory to humans. In its postcard apex in the 1960s, the Salton Sea was populated and played by boaters and bathers. Today still the lake is a site of play, though now with a creativity and flexibility that rides not in the wake of boats but in the swirl of zoning regulations: the exemplary player then the waterskier, and now the member of the board of the San Diego County Water Authority.

If you like to exhaust a set and I like to list, we may enjoy opening an expanse. If you like to be trapped and I am holding a charged space, we might enjoy a slow release. If you like to recede and I enjoy disappearance we may find mutual solace in a wide landscape. If you value communicativity in excess of sensibility and I like edges we may enjoy deconstructing a landscape.[3]

Snow Melt (non-saline), 149ml. Snow from Route 38, San Bernardino, CA. Received 9 January 2016.

In the downpour that breaks the drought, we run across the wet sand to the water in order to sample the sea. And later, we will receive other samples of waters as our moods and the weather will allow: a saline puddle, a receding reservoir, a desert spring, and so on. We are following a logic of water, we say: water which would not want our rules rigid and regular. Instead of taking samples, we receive.

The development of the figurative sense of ‘undermine’ is coterminous with that of its literal sense—and both date several hundred years before the Industrial Revolution.[4] Of course now both valences are colored by the regularity of industrial mining. Dry lake beds often hold deposits of minerals that cannot be undermined, both literally and figuratively. Roadside signage today in the town of Trona, California, adjacent to Searles Dry Lake, claims that during the lake’s mining in the early 20th century, surface deposits of Borax would continually replenish every five years. Borax mining at Searles Dry Lake ceases in 1996,[5] belying whatever claims of unlimited value could be made on behalf of such replenishment.

Rain Puddle Water (non-saline), 265ml. Storm 2 of 3. Oceanside Beach, Oceanside, CA. Received 6 January, 2016.

I need a relatively flat surface to sleep on. Geology notwithstanding I mean that in a figurative sense too. Some days later, we read aloud in our tent and fall asleep. A flat and cold surface. In the morning you shift your weight and it snows. Our condensed breath has risen and crystallized cold on the nylon ceiling. Now it releases.

As the water level has fallen and the salinity risen, algae, bacteria, and virus populations have spiked in the Salton Sea—organisms which, as the nonprofit Pacific Institute points out in a 2014 report on the predicted costs of human inaction at the Salton Sea, ‘provide no value to birds or people’[6]—that is, to the more charismatic actors and victims of an environment. One blob’s toxic cloud of rotten egg smell is another’s Salton Sea booming beachfront circa 1960.

Rain Puddle Water (non-saline), 259ml. Trona Pinnacles, CA. Received 10 January 2016.

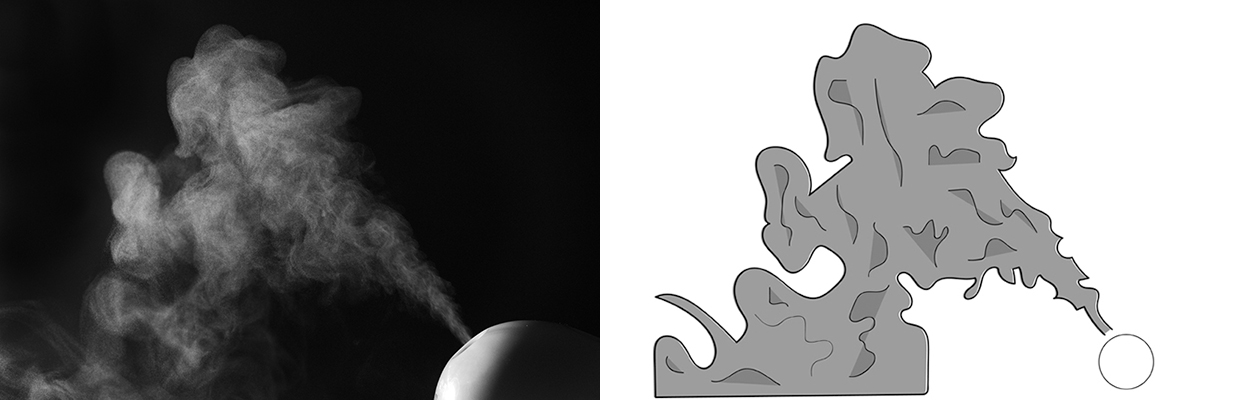

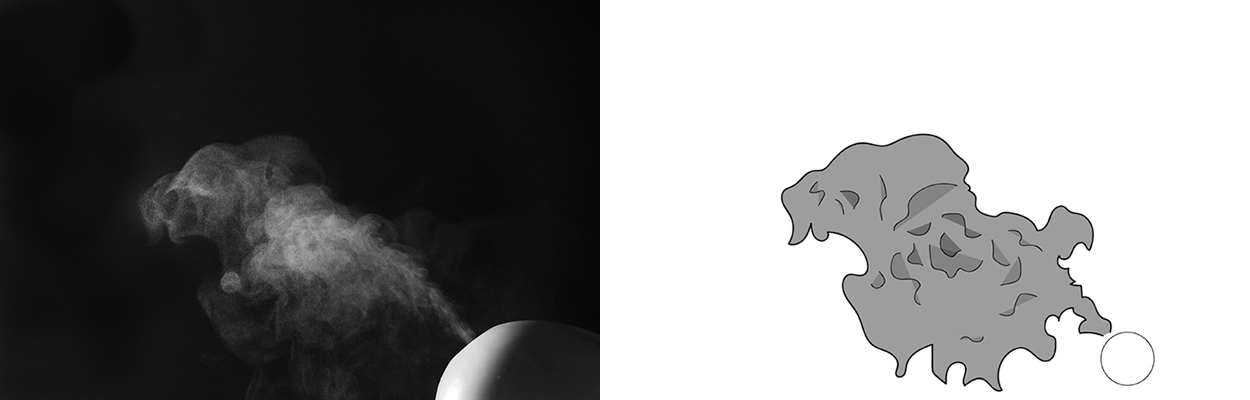

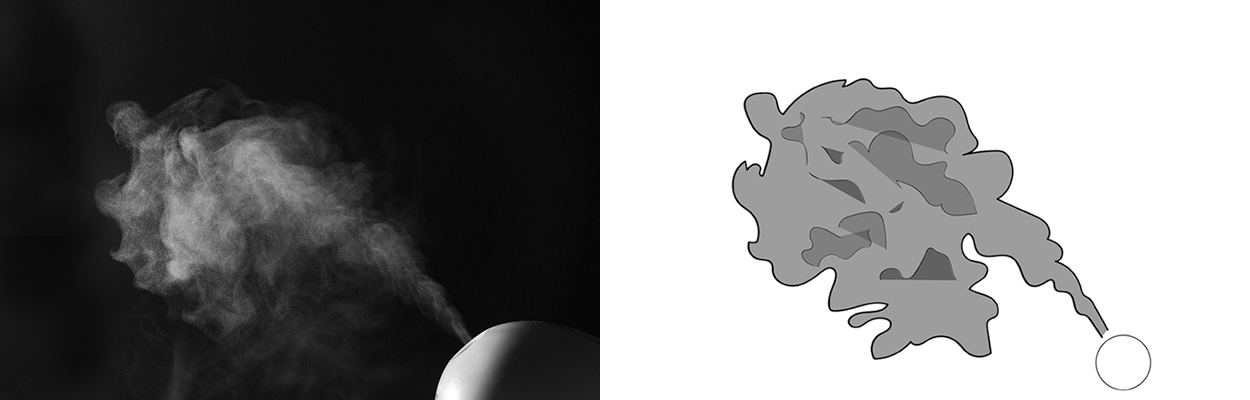

‘Presentness is grace,’ writes Michael Fried.[7] Grace is ambient. That’s not what Fried means. Ambience is a mood, but also a physical atmosphere—that which is present in the air whether we notice or not. According to some models of dispersion,[8] mushroom spores are omnipresent too—released in such quantity they form a part of the substance of the air. The spores then begin their reproductive transformation into fruiting bodies wherever local conditions slant just right. I imagine these spores as releases, eventually received, regardless of our consent. Collecting samples means following a system with set bounds.

Samples of mushroom spores are kept in folded envelopes in the collections of herbariums. With proper credentials, you can receive the original specimen in its folded envelope. The cigarette beetle is a common pest of such collections. After emerging from eggs, larvae feed for a month or two on consumable material at hand—in an herbarium, the samples of dried plant materials. The beetles however are not especially keen on eating plants that have reproduced with spores. After pupation, the beetles live for several more weeks. During this stage, they do not eat.[9] Not having prescribed a systematic approach to our sampling method, we receive what we do ambiently.

Salt-flat Puddle Saltwater, 363ml. Near Trona, CA. Received 10 January 2016.

The force that causes chemical reactions is called affinity. The formula I am more familiar with involves solids melting and becoming liquids: all that is solid melts and so on. As we drive, you read from your phone simple explanations of the chemistry of melting.[10] Even solids need energy to melt into liquid. Tiredness then, as a movement away from rigid alertness, might after all offer more than a loss. I hold rocks and then drop them again in the queer wash. This is unmethodical but not careless. A rock too of course is a record, a sample.

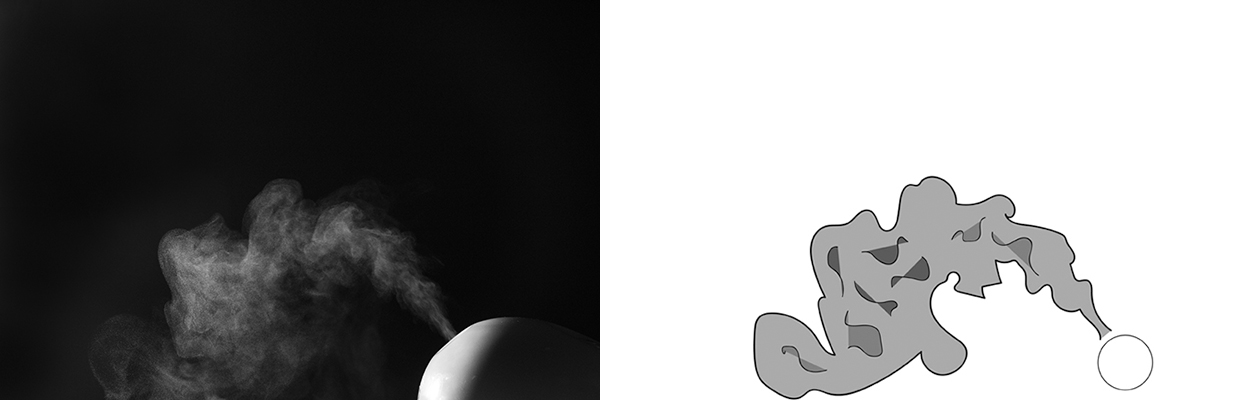

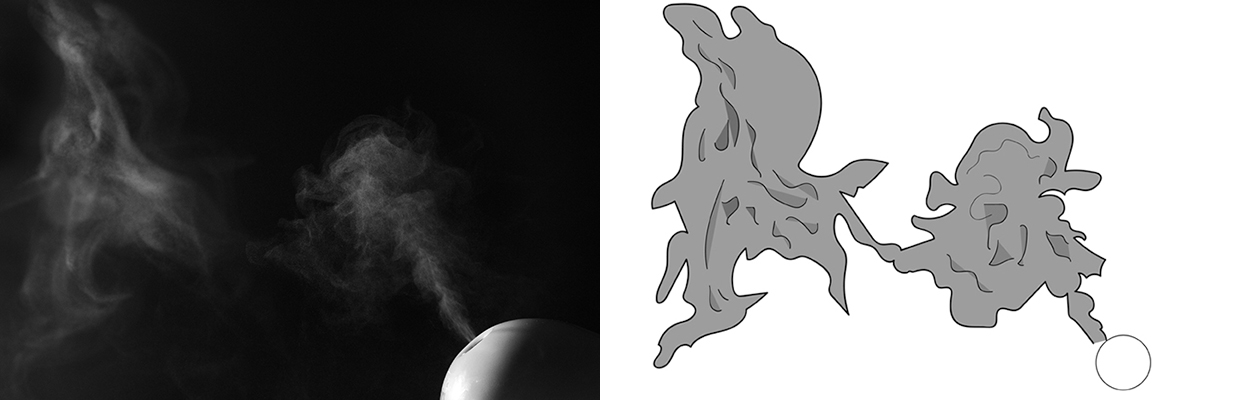

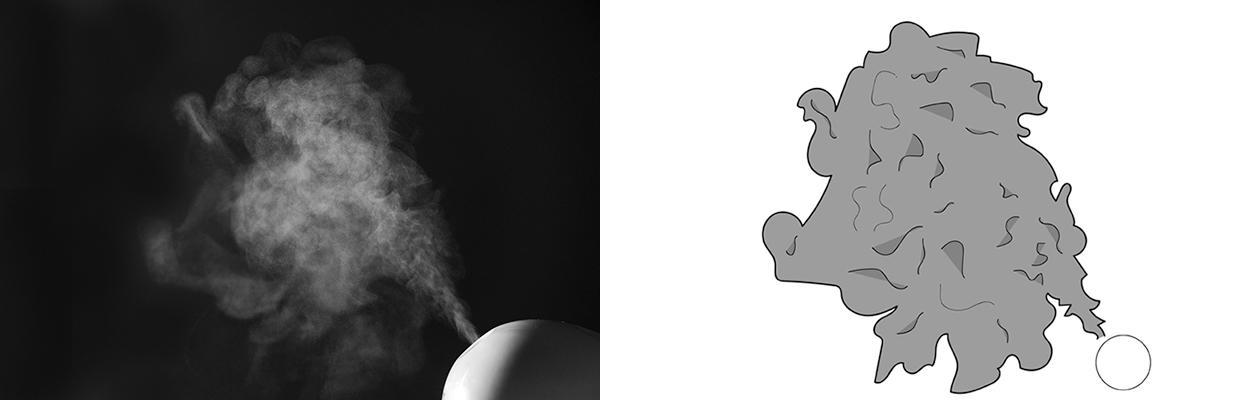

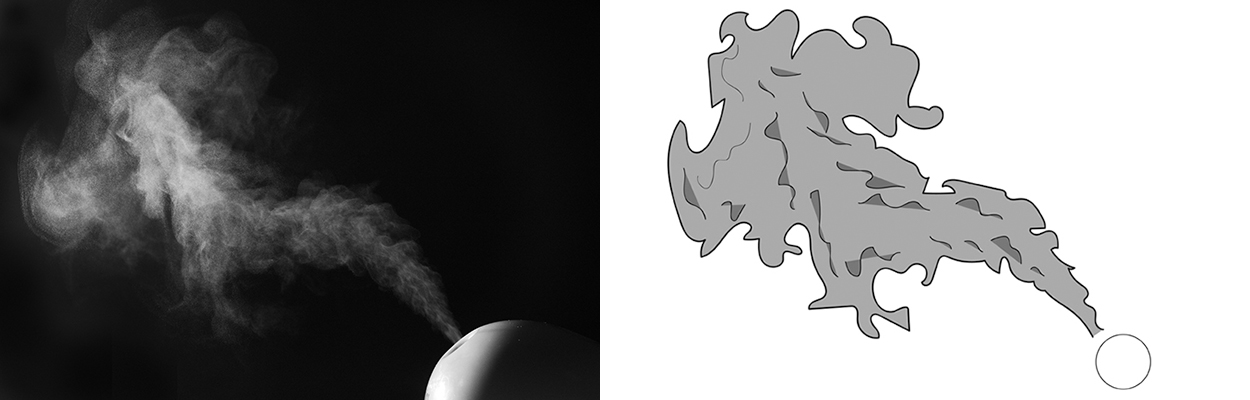

We watch a documentary about the Salton Sea[11] and I remember that John Waters, who narrates the film, lives in Provincetown—a city impossible to end up in by accident, the terminal of a two-hour drive down the arm of Cape Cod. Our sampling method means we too end up in places not on the way to anywhere else. Or instead that we only arrive at places by contingency, moved by atmospheres as much as associations. A methodology defined by fluidity and scarcity then can have no pretense toward rigidity and thoroughness. In other words, the bonds we seek out here aren’t those of solidarity, but liquidarity. When we return home, we empty our water samples into humidifiers and release the water back into the air.[12] The vapor fogs the windows. And then goes elsewhere, becomes atmospheric.

Ocean Water (saline), 359ml. Pacific Ocean, Santa Monica Beach. Received 5 January 2016.

We are informed by the rest stop signage that salt from Searles Lake in Trona “enhanced oil production in peacetime.” Borate was pulled from the lake bed and put into products designed to hold things, like Pyrex containers.[13] PYROBAR, another borate product produced from the resources of the lake bed has no water molecules bound up in it, which makes it resistant to fire but not strong.[14] I don’t care to be strong either. Back online, I watch the videos of water cake.[15] It purports to be a cake but it is a translucent blob, a half-sphere plop bobbing on its plate. We stay in bed the day after my birthday, the remainder of the water cake from the night before stored in a Pyrex container in the fridge. A few miles outside Trona, we dig into a muddy puddle in order to receive another sample.

Ocean Water (saline), 250ml. Pacific ocean, Oceanside Beach, Oceanside, CA. Received 6 January 2016.

While Trona’s founding myth is of the nearby lake bed’s inexhaustibility (proven untrue now by the economic downturn evident in the town’s shuttered houses), the Salton Sea’s founding myth is of contingency and temporality, with the sea’s origin literally an accident of a breached dam on the Colorado River.[16] And while the management of Searles Lake has been passed down and shifted through a series of owners and interests all operating under the same industrial facade, the management of the Salton Sea has erratically jerked from agriculture to recreation to resource, awkwardly prototyping the Silicon Valley value of flexibility between work and play. We are not far here from that valley. With no physical inputs and outputs, virtual channels are carved and claimed for the Salton Sea: the 2003 agreement between players in the Imperial Valley set aside an amount of water each year to be redirected to the cities where these players live.[17] Over the 75 years of the agreement, the redirected water will amount to 4,888,500,000,000 gallons of water, which according to some questionable calculations I’ve performed and whose sources I’ve now forgotten, is about 86% of the volume of all the oil we’ve used on earth since 1870.

Inland Sea Saltwater (saline), 331ml. Bombay Beach, Salton Sea, CA. Received 8 January 2016.

If you liked to imagine that you were a solid and I was getting warm, we could have enjoyed a particular kind of erosion.

I leave the soft salt crystals that we collect at the edge of the lake bed. Logistically, they are too large to carry back on the plane, and their tentative crystalline structure would have disassembled. And as well I leave the soft salt crystals that have collected themselves at the edge of the lake bed.

If you do not enjoy distinguishability and I do not notice you we may enjoy our not finding each other. If you like to deflect and I like to deflect, we might enjoy taking slightly different paths.

We take separate planes back from our sample-receiving trip, fossil fuels expended but not exhausted. The oil reserves we now draw on were concentrated over a duration when plants died but there were yet not bacteria and fungi[18] born with the capacity to break them down. I imagine these plants as prehistoric plastics. I imagine that you are a solid. I imagine the energy that propels us into tiredness. Months later, we lie hidden in the dune grass behind Provincetown and read aloud again. I am absorbed and only in the evening realize the sunburn that has bloomed. A sunburn takes water out of me I imagine. Another kind of release, that water going wherever it does. A release doesn’t just go, but comes back. Arrival’s overrated. Circulation isn’t.

Portrait through calcite prism. Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. 8 January 2016.

All images by and courtesy the artists.

[1]Metzler, Chris and Springer, Jeff, dir. Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea. 2004; New York: Docurama/New Video Shanley, 2004.

[2] “Quantification Settlement Agreement.” San Diego County Water Authority. Accessed January 27, 2016. https://www.sdcwa.org/quantification-settlement-agreement

[3] These italicized texts take their form from Tomkins, Silvan. Affect, Imagery, Consciousness (New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2008), 411-12 as cited by Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky and Frank, Adam. “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold: Reading Silvan Tomkins,” Critical Inquiry Vol. 21, No. 2 (Winter, 1995), pp. 496-522 (27 pages).

[4] “undermine, v.”. OED Online. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.proxy.artic.edu/view/Entry/211840?rskey=KtlkWp&result=2 Accessed January 30, 2016.

Also see Lippard, Lucy R. Undermining : A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West. (New York: The New Press, 2014).

[5] “Highlights from Searles Valley Timeline.” About Us – At a Glance, Searles Valley Minerals, www.svminerals.com/About%20Us1/At%20a%20Glance.aspx. Accessed January 27, 2016.

[6] Cohen, “Michael J. The Costs of Inaction at the Salton Sea, A Report of the Pacific Institute.” Pacific Institute, 2014. https://www.iid.com/home/showdocument?id=9256. Accessed January 28, 2016.

[7] Fried, Michael. Art and objecthood: essays and reviews. University of Chicago Press, 1998.

[8] Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press, 2015.

[9] Merrill, E. D. “ON THE CONTROL OF DESTRUCTIVE INSECTS IN THE HERBARIUM.” Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 29, no. 1 (1948): 103-10. www.jstor.org/stable/43781284.

[10] “Changing States of Matter.” Rader’s Chem4Kids.com. Andrew Rader Studios. Accessed January 25 . www.chem4kids.com/files/matter_changes.html.

[11] Metzler, Chris and Springer, Jeff, dir. Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea. 2004; New York: Docurama/New Video Shanley, 2004.

[12] French, Lindsey. “they didn’t bring enough water.” Accessed November 30, 2019. https://lindseyfrench.com/doc/tdbew.html.

[13] Woods, William G. “An introduction to boron: history, sources, uses, and chemistry.” Environmental health perspectives 102, no. suppl 7 (1994): 5-11.

[14] “Our Products – Borax.” Searles Valley Minerals. Accessed January 27, 2016. www.svminerals.com/Our%20Products1/Borax.aspx.

[15] “海外でも話題の「水信玄餅」を食べに行ってみた.” SoraNews24. June 23, 2014. Video, 0:37. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mK8meArYk1s.

[16] Ponce, Victor M. “The Salton Sea: An Assessment” San Diego State University. June 2005. saltonsea.sdsu.edu

[17] “Quantification Settlement Agreement.” San Diego County Water Authority. Accessed January 27, 2016. https://www.sdcwa.org/quantification-settlement-agreement

[18] Biello, David. “White Rot Fungi Slowed Coal Formation,” Scientific American,” June 28, 2012, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mushroom-evolution-breaks-down-lignin-slows-coal-formation/

Lindsey French is an artist and educator whose work engages in gestures of sensual and mediated communication with landscapes and the nonhuman. She has shared her work in places such as Pratt Manhattan Gallery (New York), the Museum of Contemporary Art and the International Museum of Surgical Science (Chicago), and in conjunction with the International Symposium of Electronics Arts (Albuquerque and Vancouver). Lindsey currently teaches as a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Studio Arts at the University Pittsburgh.

Willy Smart is a writer and artist whose work proposes expanded modes and objects of reading and recording—stones, insects, ponds, surfaces, hormones, spores, clouds. Willy directs the conceptual record label, Fake Music.