Alex Young

The Civil Appetites, 2013, Rochester Contemporary Art Center, Rochester, NY.

Alex Young: I want to start by asking what might seem like a fairly simple — yet perhaps-not-so-simple — question, namely: how would SPURSE describe itself to someone who might be unfamiliar with its activities?

SPURSE: You’re right, descriptions are never that easy. We are always evolving as an organization and often going in a few different directions. That aside, descriptions are about connecting and so we try to stick to useful off-the-self descriptors. These days we like to introduce ourselves as an environmental design firm or consultancy. When people ask us what we do we usually say: we help compose and recompose ecosystems with communities both human and non-human.

We quite often have at least half a foot in the world of the arts and so we get asked quite frequently (in these contexts) how is this art? It’s a fair question. We are happy to strategically circulate in the worlds of the arts, but we don’t describe ourselves as artists. A big interest of ours is how our culture evolves into new practices “after art”. We draw upon what could be called traditional art skills: sculpting, composition, and beauty. Without any sense of irony we describe what we do as collaborative sculptors of systems — and that to work with dynamic systems one needs to have a really good sense of composition (by which we mean ‘how things can work together’). Composition is no easy task. When a new system ‘works’ it is literally a work of beauty — it creates a new form of beauty which we can come to sense and learn to appreciate. Beauty is, for us, the outward expression of a new mode-of-being. This is our abiding concern – sculpting beauty via systems in a collaborative processes. So we constantly think of sculpting, co-composing and being artful, in the old sense of ‘skillful’ practices. But neither Art nor Sculpture in the capital A — Art sense of the term are that relevant to our practice or good descriptors of what we do.

Interestingly, if we happen to be in an art context when we say things like this we tend to quickly get categorized as conceptual or social practice artists. We are neither. We believe that all making is social and conceptual. Of course we understand how these terms are being used, but that said — these terms make no sense, and produce false dichotomies. Going further, the dichotomy between makers and thinkers, that the conceptual term articulates misses that we are all always physical makers. We as SPURSE collaboratively make things: landscapes, meals, cups, books, research labs, concepts, and systems. All of these involve a great deal of careful, skillful, and artful making. We are ultimately not that concerned if people see this as art, craft, design, or something else — or none of these.

These days we stay away from art labels. For us what really counts is asking ‘what needs to be done?’ and then figuring out how to do it collectively. This is why we are drawn to terms like “consultant” — we like to consult and then collaborate with the world from bacteria to buildings.

All of this is really a long way of saying that when asked “who we are”, we just explain what we are doing in that moment in a simple understandable manner so as to expand the circle of collaboration. So we usually say something simple, “we are writing a cookbook” or “we are working on developing a commons”. Ultimately, we try to describe ourselves in a way that can get people involved in the issue, or project directly.

The Civil Appetites, 2013, Rochester Contemporary Art Center, Rochester, NY.

AY: I have read that the group originated as more-or-less a band of architecture grad students eschewing the formalist tendencies of the field and the idea that ‘good looking’ design can change the world. I was wondering if you could briefly elaborate on how SPURSE developed, the scope of who was involved then and now.

SPURSE: We developed twenty years ago as a group of architectural grad students interested in alternative means of building. For us building has always been focused on building the conditions to open up the possibility of something interesting happening. It was never about fetishizing things as things but always thinking about effecting systems (which does involve a lot of the making of things as tools).

We began by experimenting with various forms of urban interventions: A wall that slowly moved over time, or giant tower that just appeared without explanation on a contested piece of land, or renaming areas with conventional looking signage. Our ethos was experimental: ‘what could happen if….?’ And then when something began to happen: ‘what could we add to this…?’, ‘And now what….?’, ‘And now what…?’ We have always been interested in probing, following, joining, catalyzing and responding to complex emergent situations.

Back then, there was a core group of maybe seven of us and a larger group of up to sixty that came in and out of projects. Over time this has changed. Now there are ten of us and four of us have been hanging around since the beginning.

sub-mergings: a wetland project, 2006, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN.

AY: Yes, in the past, I have seen SPURSE described as an architectural collective with no fixed members and its ranks basically fluctuating in number between as few as 4 and as many as 40.

SPURSE: We worked then as now as a collaborative. This comes from understanding that all action is a collaboration. To carve a wooden cup it to collaborate with a forest, a tree, tools, histories of objects, hands, drinking and much else. To be a collaborative is not just about people and it is always necessarily open. Our philosophy is to see all of the parts of the system as partners with real agency in the process. I think that this is what differentiates ourselves from many other organizations in art, ecology, or other related fields. Collaboration is the ontological condition of our action.

Our “policy” has always been that anyone can join SPURSE and so the number of self identified “members” has fluctuated like you say from 4 to 40. But saying this gives a false impression of things being really free-wheeling and chaotic with people coming and going freely. It is very self selecting — most people imagine it is far more interesting and glamorous than it is. Usually it is just lots and lots of mundane work. That said, there is now a stable core group of ten of us.

Where things really fluctuate is when we are working on projects. Because we work collaboratively with organizations and communities, most often there are dozens of people involved and in this way there are “no fixed members” as you put it. This can be a challenging to co-ordinate and so developing systems and processes to coordinate everything and still get to innovative ends is one of the most critical skills that we bring to the mix. This is especially true as projects often take many years and take on many different forms.

DeepTime/RapidTime, 2007-2009, Grand Arts, Kansas City, MO.

AY: I am curious how SPURSE negotiates agency, roles, and responsibilities within the group? For instance, Critical Art Ensemble has written somewhat obdurately that collective cultural actions should be approached as a small band that is tightly affiliated with little redundancy in skill sets. How might SPURSE describe its model of group dynamics?

SPURSE: For the members of SPURSE, we don’t have rules to how to participate. Most often someone outside the group invites us to work on something, and if any of us are interested we will accept the invitation. Sometimes this means only two of us are working on something, and sometimes more — it is totally up to each of us to how we participate. What matters is that we are each responsible for following through.

We have been working together for a long time. We all have very different skill sets: some of us can build exceptionally well, others are urban planners and solar energy engineers, others renewable materials or indigenous community design, etc. etc. So, depending on the project, different skills are called upon and different people take the lead. This allows for a pretty open and flexible structure with people coming in and out of projects as makes best sense in terms of what needs to be done. This flexibility really matters — for how does one know what should be done at the beginning of any endeavor? Most of our projects evolve over many years and pivot, leap and shift in all sorts of unknowable ways.

For us friendship and the long-term sense of joy, concern, and love that comes from it really matters.

We have been in museum shows with Critical Art Ensemble but we don’t know them well enough to say much that is meaningful about their methods. No doubt Critical Art Ensemble is right in regards to their interests. But we are not that interested in cultural action if by this we mean human and/or art focused. Our concerns are ecosystemic and, as such, their model would never work for our interests. For us, what matters most is working from within on-going systems with collaborators of all kinds from humans to non-humans at many scales.

Pitzer Multi-Species Commons, 2015, Pitzer College, Claremont, CA.

AY: How has your collective mission and practice transformed or grown over time?

SPURSE: Our practice has definitely evolved and transformed over time. Early on we were experimenting with performance and urban interventionist practices. We did a number of projects that were properly speaking multimedia theatre/dance/movement hybrids. These taught us directly about embodiment, technology, habit, and how ultimately the ‘medium is the message’. Our early interventions were types of urban research probes. We did these all over North America from Mexico City to Montreal and beyond.

This shifted into a lab phase where we set up various types of research centers. We set up a center to study urban systems. The success of this project led us to develop this model and use nomadic research centers as a way to investigate phenomenon that puzzled us in an open collaborative situated and on-going manner. This work focused on an environmental rethinking of our entanglements “after nature”. We looked at urban ecosystems, interior ecosystems, entangled microbiomes, new forms of time with these tools.

From this, we have shifted into a more directly ecosystemically engaged practice. Where previously we speculated on how things could happen, now we are interested in working to make things happen. We work at a systems or ecosystems level to catalyze and co-emerge with new possibilities. These projects tend to be more complex, nebulous, and long term. Our ‘Eat Your Sidewalk’ initiative is a good example. I know we are going to talk about this later so I’ll just stop here.

Micromobilia: Machines for the Intensive Research of Interior Bio-Geographies, 2005-08, installation view from Experimental Geography, Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.

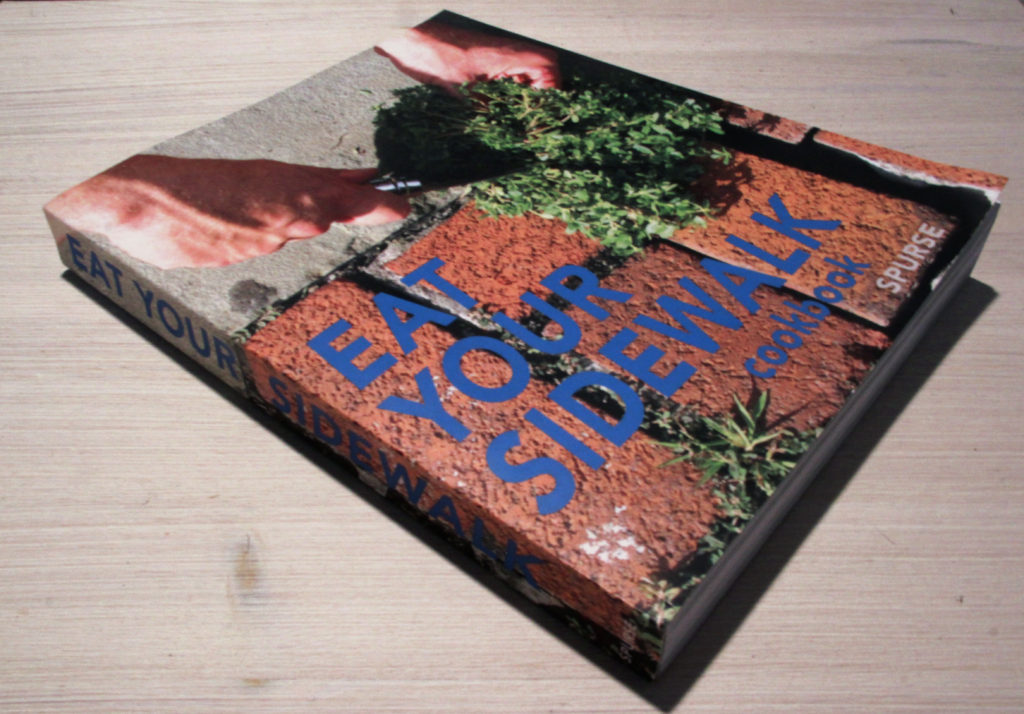

AY: Well, let’s talk about the ‘cookbook’. The ‘Eat Your Sidewalk Cookbook’. It is readily apparent to anyone who has given the book even the most cursory glance that this is not a ‘cookbook’ in the conventional usage of the word. How was it determined that SPURSE would produce a ‘cookbook’ and why retain such a classification?

SPURSE: Cookbooks are amazing! Cookbooks often don’t get the recognition they deserve. They are looked down upon as either too practical or just something commercial. Cookbooks are truly the most experimental of all of the book types. One buys a cookbook on the premise that you will do things. While most books work internally cookbooks ask you to experiment in new ways with the world around you to change your habits, your sense of taste, and even what other species to engage with — is this not wonderful? You open yourself to changing, learning, following. You open yourself to meeting and working with new species. This what we learnt from cookbooks and what came to really interest us in writing a cookbook. Think about it — if we were to write an academic book on ecology and alternative practices it would be at most a tool for intellectual argument — a cookbook on the other hand has a big reach and engages with those will to change themselves and the world around them.

The Eat Your Sidewalk Cookbook is not your usual cookbook, if by this we mean one that is personality or restaurant driven with most of the space being given over to step by step food based recipes sprinkled with the odd illuminating anecdote.

Just to add a bit of context. We love cooking and how it entangles us with so many critical questions. Eating entangles us directly with other species, environments, pleasures, habits, and practices. Over the years we have opened four, what now would be called, pop-up restaurants. While working on environmental and food related questions we have amassed quite a cookbook collection as well as our own set of recipes, procedures, and games. So cooking, eating and thinking about what, why and how we and all others eat is central to everything we care about.

Our main position in starting any project is that doing shapes thinking. Academic books have this backwards, they function on the opposite premise: thinking comes first and then shapes what is done. Because of this we were never happy with the thought of writing an academic book. We wanted a book that would be integral to someone’s daily life and actions.

Our cookbook is an odd cookbook in that it has recipes for far more than what is usually considered recipe materials. We have recipes for “Scarcity” and “Nature” as well as “Mead”, “Canada Goose Tartare”, and much else. These recipes are part of a sustained effort to re-think and re-shape our basic habits and frameworks. Additionally, it is an odd cookbook in that it is equally a work of speculative anthropology, philosophy, and even travel writing.

So, yes, it is a book that could be dismissed for merely being a ‘cookbook’. But we like the company we keep in this dismissal. In our minds some of the greatest works of philosophy, political science, ecology and erotic literature are cookbooks.

Keeping the classification ‘cookbook’ is really important to us. We intend the Eat Your Sidewalk Cookbook to be something that is used and that meets people where they are. We want to be met and meet others in the middle of everyday life. A cookbook is perfect for this. Philosophy, ecology, politics, cosmology love and curiosity should emerge from the everyday, and return to the everyday — they belong in cookbooks. Obviously, in doing this the ‘cookbook’ changes. We are really pleased with the strange new creature that is the Eat Your Sidewalk Cookbook.

Eat Your Sidewalk Cookbook, 2017.

AY: Throughout SPURSE’s oeuvre there appears to be an underlying tendency to locate abundance in place of perceived scarcity or nothingness. How does SPURSE regard such dualisms as abundance/scarcity, thingness/nothingness?

SPURSE: Yes! Excess: Everything is more-than. Surprising. Swerving. Unexpected. In everything we do is connected to an engagement with an open world of unknowable otherness and newness. But, that said, we are doing something different…

Scarcity/abundance, something/nothing. Binaries are best moved away from. The philosopher Whitehead suggests “turn every opposition into a contrast…” Abundance and scarcity or something and nothing are not in opposition to each other — with one or the other term being ultimate. Rather they are two points of attraction in a much larger field of contrasts and dynamic emergent possibilities. These are points that flip, merge, dissolve and give way to other points… There are ways to shift these fields such that the totality of the binary dissolves into things quite different. This is where we locate our practice.

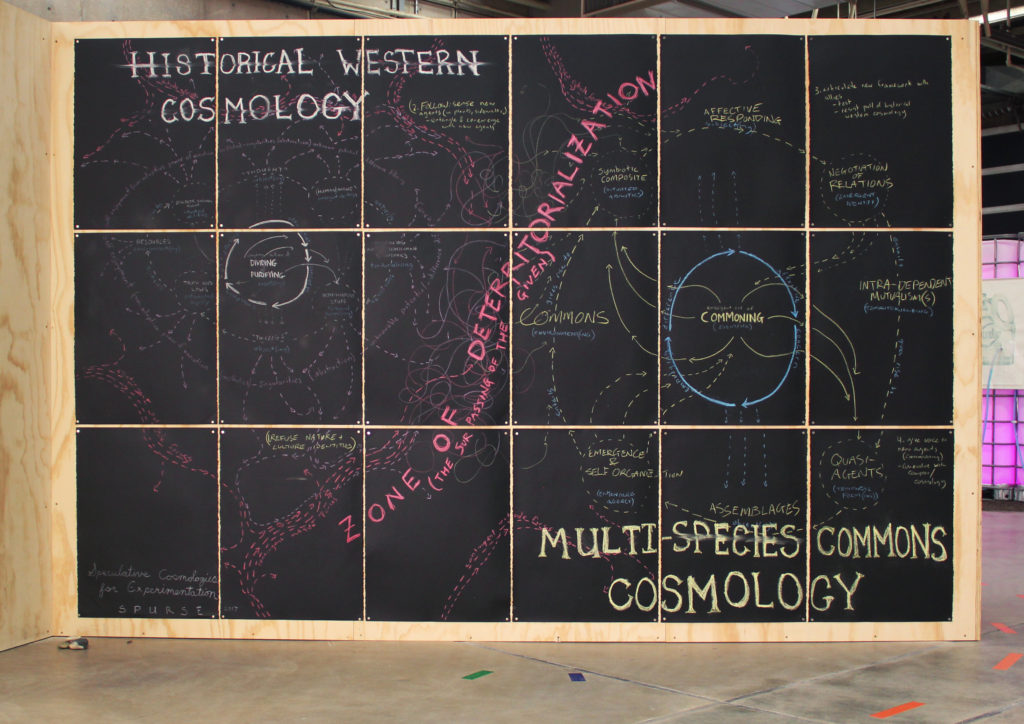

We are always having to work through and out from under Scarcity as the fundamental invisible framework that underlies so much of the Western Cosmology and our default cultural mindset. We, as a culture, are constantly producing scarcity. It is really important to see this. It is not that scarcity exists, we produce it. Privatization, resourcification, are good examples of this. Scarcity is something that is too often misunderstood within the environmental movement — who are ironically one of the great producers of it! The idea that we ‘need to protect scarce resources’ is a flawed one. Our argument is that we need to shift from the “scarcity + abundance” model to one that produces and supports the conditions of fecundity or livingness (which is not the same as ‘abundance’). This shift is one that involves moving from inter-dependence to intra-dependent — from being-with to a being-of.

We understand this project to be one of co-evolving away from the Western Cosmology towards emergent new cosmologies (and connecting to ongoing non-western cosmologies). Key to this is to avoid all of these dualisms (abundance+scarcity, something+nothing, nature+culture, art+craft, human+non-human, etc.). Now, just not to be misunderstood, because this is critical, when we say it is important to avoid these dualisms — we mean that it is important to avoid them in totality — both terms — neither nature nor culture. This is what we mean by “after nature” and “after art” — we wish to work our way out of these frameworks — not just choose one side. We are conscious in our avoidance of slipping into just flipping these binaries on their head: ‘let’s privilege abundance, thingness, and nature’.

How is this done? In happens in our daily lives. The path away from the problems of the Western Cosmology begins for us in doing a few very mundane things which is what the cookbook set out to do.

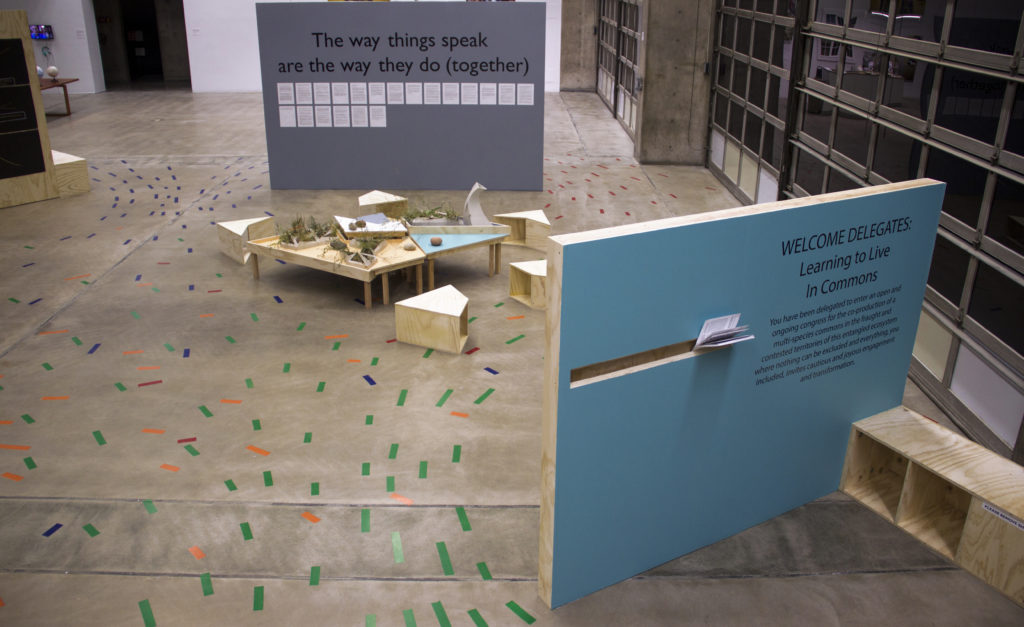

WELCOME DELEGATES: Learning to Live In Commons, 2019, installation view from GROPING in the DARK, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ.

AY: SPURSE has described the act of eating your sidewalk not only as an entanglement across species but also as a means of temporarily transforming space—particularly privately owned space—into commons. Though certain places like the Nordic countries provide protections for such actions with laws permitting the freedom to roam, by United States standards I cannot help but perceive an inherent, albeit quiet, radicalism to the act of eating your sidewalk. Considering the privileges and protections of private property in many places, I imagine it is not inconceivable that one might run afoul of property owners and the law by eating place. I am curious if SPURSE has had any encounters of this nature?

SPURSE: It is wonderful that you see this quiet but insistent radicalism. The book is both an act of cosmological and civil disobedience. We jump fences and occupy space to activate new forms of the commons. From an ecological perspective property boundaries are problematic. Nothing stops at a fence — plants, fungi, weather, pesticides — their boundaries and thresholds are quite different. Reality does not come in discrete units but in dynamic networks. We need to evolve practices that follow and support intra-dependent entanglements.

Eating your sidewalk — or ‘eating place’ — and urban foraging are fundamentally practices of producing intra-dependent networks. We understand this to be at the heart of commoning. We make commons when we refuse, ignore, subvert all forms of ownership with usership. But this means more than the freedom to move across something. We are interested in a reciprocal exchange with a landscape. Foraging is just that: it involves effecting the landscape via picking and eating. We wish to foster practices of producing dependencies, interdependencies, and intradependencies. This is our real radicalism — we do away with the spiritual model of ‘nature’ in which we should ‘only leave footprints’. We do not want to be reduced to tourists, we wish to dwell. What was called the enclosure of the commons — the moving people out of a land is now complete — we are no-where intra-dependent in any active sense of the term. Ownership today is fundamentally about producing independence — separation — and this is something that is always an act of theft.

We meet with resistance all the time. But rarely is it an altercation. We wish to connect. We wish to act as exemplars. We try and talk. We share what is wonderful, pleasurable, and important about foraging. Often there is a connection to parents or grandparents foraging. Or foraging in the country that they might have historically migrated from. Altercations are sometimes critical to politics but the pleasures of food, eating, and connecting to a landscape can be a constructive means around a head-on collision of values, power, and interests. Our worldview is relational and thus negotiated, experimental, and evolutionary.

The Civil Appetites, 2013, Rochester Contemporary Art Center, Rochester, NY.

AY: More broadly speaking, how might SPURSE place ‘eating place’/ ‘eating your sidewalk’ in the general realm of human politics?

SPURSE: Our politics is one of direct action and multi-species co-composition that does not neatly fit into our contemporary political landscape. We imagine the evolution of a new cosmology that does not begin with the individual and its rights as the basic unit of political thought. We begin with the commons defined as “being-of-a-shared-association”. We wish to ask: what needs and rights should this association—this act of commoning have? How do we co-shape and support such emergent associations? Another word for commons or association is place. But place should not be thought of as a container: ‘nature’ or ‘the environment.’ Place is not something extra that surrounds ‘us’ it is this ‘us’ this shared association. Place is a dynamic network of intra-dependencies. This ‘us’ is all species that make up a ‘being-of-a-shared-association’.

Our current investigations are looking at how this alternative ecological framework can — alongside the concept of plentitude — offer alternative possibilities of co-shaping. In this way, we are not part of the traditional environmental movement and its alignment with the institutional left and the politics of top down regulation. A different “we” from the generic “human” we. Our contention is that eating differently — eating as placemaking on this model of the commons is a new and useful form of political engagement. The commons are not forms of space but an activity of commoning. For us an eating place is always multi-species. When we eat our sidewalk we are entangling with the lives of all other creatures who are dependent on each other.

WELCOME DELEGATES: Learning to Live In Commons, 2019, installation view from GROPING in the DARK, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ.

AY: With ‘Eat Your Sidewalk’ being released within the past couple of years and after over half a decade of work, have SPURSE’s tendrils begun reaching out into other projects? Or rather, as I have been following the posts on the accompanying blog, perhaps I should ask: are there plans to develop the cosmology of ‘Eat Your Sidewalk’ into new entanglements?

SPURSE: The cookbook itself began as a tangential outcome of a number of projects and now its tendrils are reaching out in all sorts of interesting directions. That was always our hope and so it is wonderful that this is happening. We are doing many readings and foraging workshops to help catalyze these practices and questions. We are developing urban design templates and other tools that communities can use to re-imagine their eating-places (urban ecosystems). We are building boats to engage our urban marine commons, and trying to develop new tools for intradependence. We are working on how to engage with what normally would be thought to be outside of sentience: rocks, clouds, ideas, and events as as sentient beings…

We In a very real sense we are still at the beginning, we are putting out this work into many different food, ecology, commons, and urbanistic contexts and seeing what impact it has. We follow and grow with these experiments.

All images courtesy the artists.

SPURSE is a creative design consultancy that focuses on social, ecological and ethical transformation. SPURSE works to empower communities, institutions, infrastructures, and ecologies with tools and adaptive solutions for system-wide change. Drawing upon diverse backgrounds that span the fields of science, art, and design, they utilize unique immersive methods to co-produce new ecologies, urban environments, public art, experimental visioning, strategic development, alternative educational models, and expanded configurations of the commons.

Alex Young is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, and curator who explores the interplay of both human and non-human actors as they engage in the collaborative shaping their environments. Presently, Young’s work consists of multi-media, sculptural, engineering, curatorial, and literary projects that explore ruderal futures—or modes of actualizing speculative forms of co-creation with vegetal, animal, and fungal actors best adapted to thrive in environments distressed by human activity. Young’s solo and collaborative works have been presented at numerous venues internationally including Conflux at NYU, Brooklyn International Performance Art Festival, and Flux Factory in New York, NY; Kiasma Museum and Alkovi Galleria in Helsinki, Finland; ACC Galerie in Weimar, Germany; Stadtische Museen Zittau in Zittau, Germany; Spanien 19C in Aarhus, Denmark; SDAI in San Diego, CA; Beyond/ In Western New York Biennial, UB Art Gallery, and Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center in Buffalo, NY amongst others. Past curatorial projects include: GROPING in the DARK at Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson, Universal Dissolvent: Fragments from the Southern California Megalopolis at the San Diego Art Institute, A Haven at ACNY Exhibition Space, and Space Was the Place at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.