Courtney Kemp

Colin and I are both trained metalsmiths who choose to work in other media: it is this foundation that has been the bedrock of our conversations over the past five years. We have both arrived at studio practices that push against the rigid, meticulous world of the jeweler, yet we still retain a sense of refinement and poise within our respective ways of working.

The following has been reworked from the interview that appeared in the Portland2016 Biennial Reader.

Convoluted I, 2017, Cement, acrylic paint, wire mesh, Tobasco caddy. 25″x21″x6″. Photo by Jason Horvath.

Courtney Kemp: I bet you are tired of answering this question, but since I haven’t asked you before…as a contemporary example of someone who is indexing spaces, what do you think differentiates your pieces from Rachel Whiteread, who is taking negative casts of spaces as an index, displaying them in a white box outside of the spectrum of their original sites? Do you feel that there’s a similar conversation in those ideas of indexing to what you are doing, or do you believe there’s something exacting and different about using disposable materials?

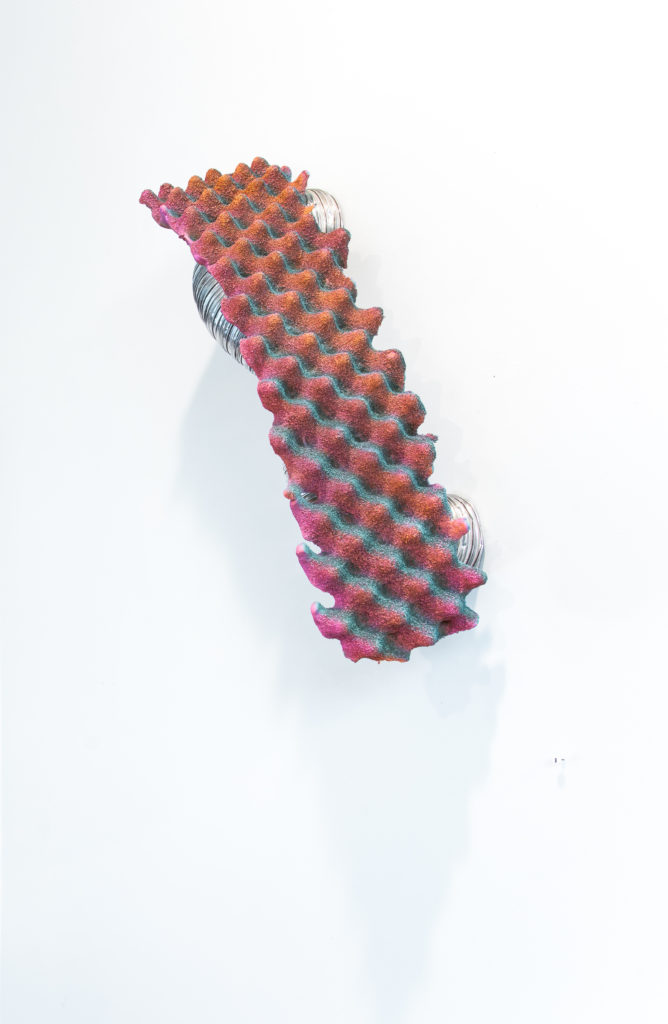

Convoluted II, 2017, Cement, acrylic paint, wire mesh, aluminum flex pipe. 20.5″x14″x8″. Photo by Jason Horvath.

Colin Kippen: I think there is a difference: these are casts of things that are a part of the waste stream. You only need the fruit divider for shipping apples and since this is all Styrofoam it’s completely spent after one or two uses. I like to think about things we see so often, or what the guy working at New Seasons [grocery store] sees so often that they mean nothing to him. I think there’s a reverse, these things we see all the time that mean nothing, I’m trying to have you see a few of them and have them mean something more. The things I’m collecting are all boundary textures—they separate something. Bubble wrap separates the fragile piece on the inside from the careless Fedex workers who could crumble it. The fruit dividers protect the fruit from the shipping. The to-go container nestles your Thai food. But it’s always something that’s discarded once the meal is done. The rotisserie chicken dinner tray, for instance, allows you to have a great meal with your family but it’s tossed away right after.

Reap/Sow V, 2016, Cement, perlite, shovel handle, wire mesh, binding wire, acrylic paint. 12.5″x7.5″x3.5″. Photo by Evan La Londe.

Rachel Whiteread is doing something where she’s taking the entire inside of a house and trying to equate the feelings of loss and emptiness with the physical size and weight of that internal space. When her father passed away, the overwhelming grief could fill a house, so this was the physical embodiment of that grief. I think there is something similar in my own work—my dad passed when I was 10—and the grief after 25 years is not enough to fill a room but it is enough to fill a rotisserie chicken container. It’s these small things that relate to my experience as a member of a family—it’s part of our daily life—and there is some element of sadness and loss when the meal is done and you’re cleaning it up or recycling it. I’m filling that absence with concrete. I wrote about Whiteread in my thesis and thinking about the index in terms of photography, where she was “3D printing” the void of various objects, whether a stairwell—she’s been doing some smaller things recently…a lot of resins—

CKemp: Yeah, like those transparent pink and purple pieces…but they’re more object-based than space-based.

CKippen: Her work runs the full gamut from small thing-based pieces to massive full-sized houses. I like thinking about these as 3 dimensional photographs with the airbrushing being like the developing of color, or if it’s an analog 3D printing of something, then print development happens with the paint. That’s where the highlighting and the color interest comes in. A lot of the original photographers in the 1830s were scientists sorting out the taxonomy of plants and animals. I’m like the 3D version, now, developing the taxonomy of manufactured castaways.

My work really centers on making the banal interesting—trying to figure out that line between the banal and the special—and that idea of playing with the spectrum of sculpture to painting, or sculpture to photography. There is a definite relation to the waste stream—these things that are so common we don’t see them anymore and we don’t care enough to keep them. I am also attempting to showcase some of the back-story: I think about the dude or the girl who is designing these things: they’re really beautiful textures!

Reap/Sow II, 2016, Cement, perlite, shovel, wire mesh, binding wire, acrylic paint. 19″x14″x9″. Photo by Evan La Londe.

The fact that these are artificial things separating natural pears…there’s some need for those squiggle lines, for the manufacturing of the air cushion, but I don’t know why…

CKemp: As in, what’s the difference between a grid and a lovely organic squiggle?

CKippen: Right, why not just make a structure that’s purely functional? Why design them to be beautiful?

This was a pair of fruit dividers, just cellophane that would not hold the concrete well and, for me is a great example of the concrete giving me only a 30-minute window. I wanted to get a decent cast of the texture so I laid the two trays side by side and was thinking I could just effortlessly drape them over the top of the trashcan and that they would stay there.

Rubbish, 2016, Trash can, concrete, shredded personal documents, wire mesh, spray paint. 20″x26″x15″. Photo by Julia Saltzman.

I didn’t wait long enough for the concrete—there’s a specific time in the curing process where the concrete is soft enough so that you can push through the mesh so that it stays to the form—and it was doing that just fine but that meant it was dripping down, so I was pushing and prodding these little cells so they would gain some of the texture of the cellophane, and it was this 30 minute nightmare where it was just dribbling off. But the result is this form that has a strange pustule look to it that wouldn’t have been there if it was just the even gridding of the original version. The dialog with materials is very important to my practice: the concrete wasn’t letting me do exactly what I wanted but there’s something really nice about having it as the referee in the situation. I think it would have been more boring had it been an organized arrangement of the fruit platters. So that’s the part of me that really has that material-based practice where it’s necessary for my ego to listen to what the concrete tells me. It can’t be just a top-down design…my thought was this would be a neat little row of fruit divider cells, but concrete told me differently. That’s important for how these things manifest themselves.

Bracket, 2016, each piece: roofing bracket, concrete, shredded personal documents, wire mesh, acrylic paint. 15″x23″x15″. Photo by Julia Saltzman.

The pock-marking here…you would never want to hire me as a concrete mason. There’s a lot of shady stuff going on with all of pieces I make: they are not engineering-grade. That’s been one of the more freeing/uncomfortable things about this process…I could do some more research and figure out how to get all the bubbles out, but I think there’s something neat about the material confusion.

CKemp: You have to wonder if some semblance of ‘material perfection’ would actually negate the reality of your processes. There’s something valuable about having those crevices and pockmarks to speak to your process. But then those spray painted plastic skins come in and are wildly different from this original, process-based surface. You have both the recognizably fake and recognizably real in one piece.

CKippen: When you mention that about surface and the fakeness of the front: it doesn’t have to be done on cast concrete. I could just attach the actual thing to the bracket and then paint it. It is something that I am interested in and I do paint actual things like rocks, almost as practice for my painted sculptures. There’s something fun about texture, light and color play that can happen on the actual object but for a sculpture to really work for me, it has to be that index of something that’s absent.

Ironing Doord, 2016, Concrete, ironing board, wire mesh, binding wire, acrylic paint. 70″x32″x32″. Photo by Mario Gallucci.

In my material list, I’m not telling what I cast into, I’m saying this is concrete, spray paint, bracket, and wire mesh. I’m never telling you they index fruit dividers.

CKemp: You don’t have to understand that in order to absorb the piece, which is nice. You’re not asking the materials list to explain the work, like “cast from fruit tray.” There’s something useful about that loss of information…I want to assume everything I can about what this original material was. You know this is not a handmade object because you see those mold lines, where you imagine that Styrofoam or plastic was injected. There’s something exciting about that mystery, where you allow a little bit more breadth in the conversation with your work.

CKippen: And it’s in that sort of shift between banal and special, there’s something about the viewer’s experience that’s really integral to that. I had a piece in my MFA show that was just the casting of the OSB plywood. For most people, you walk by OSB all the time with new construction and various floors that aren’t finished, but for people who work with that stuff all day every day, it is completely banal. There are two different kinds of banality: the kind where it’s so commonplace that you never notice it, and then there’s the kind where you’re working with it all the time and you’re just bored with it…

Zeugma (Ply), 2015, Concrete, wire mesh, tire, spray paint, binding wire. 50″x29″x23″. Photo by Colin Kippen.

CKemp: Some type of ‘hyper-familiarity’?

CKippen: Yes! I think that’s interesting, most people only see the quasi-geological aspects of the cast OSB but for a very small percentage of people they will automatically recognize it as the plywood. I love that variety of visual meaning, that’s true of words too…there’s a part early on in “Little Prince” where the guy says “draw me a sheep” and he draws a sheep and it’s like “no no no, that one has horns”…the word sheep for me, I conjure up very specific sheep in my mind and so do you, and the word sheep is a box that contains an infinite number of sheep conjured in everybody’s minds. We all have sheep in our brain so it works—the word signifies the thing—but there’s a distance between that sheep in my mind and your completely different sheep yet they both share the word…that’s another linguistic corollary that I like to play with, that spectrum between banal and special is the same as the spectrum that any word has for it’s referent. We structure everything by words and yet there’s a slipperiness behind it all that’s kind of daunting.

CKemp: But also exciting, that idea of interpretation of a word, image or object is absolutely endless.

All images courtesy the artist.

Colin Kippen was born in San Francisco and grew up in rural Vermont. Along with a nine-year apprenticeship to a jeweler, he holds an MFA in Craft (2015) and a Post-Bacc Certificate in Metals (2006) from Oregon College of Art and Craft along with a BA in Studio Art (2004) from Carleton College. He recently completed a residency at Bullseye Glass Factory in Portland, OR. Past exhibitions include a solo show at Duplex Gallery, Portland OR, group shows at the Portland2016 Biennial, Portland, OR; SOIL Gallery, Seattle, WA; Dakota Art Gallery, Bellingham, WA, Eastside International, Los Angeles, CA, Paragon Gallery, Portland, OR and Here/There Gallery, Portland, OR. Colin is on the faculty at Portland Community College and Clark College in Vancouver, WA. He lives and works in Portland, OR.

Courtney Kemp is an artist and educator based in Portland, Oregon. Recent exhibitions include Spaceworks (WA), Border Patrol (ME), SOFA New York (NYC), Galleri Puls (Norheimsund, Norway), Disjecta Gallery (OR), Platte Forum (CO), and Heidi Lowe Gallery (DE), among others. She is an alumni member of Ditch Projects, an artist-run collective, and serves as faculty in the graduate programs at Pacific Northwest College of Art. Her practice investigates objects, fiction, and intersections of private and public sites through sculptural works.