Bertha Husband

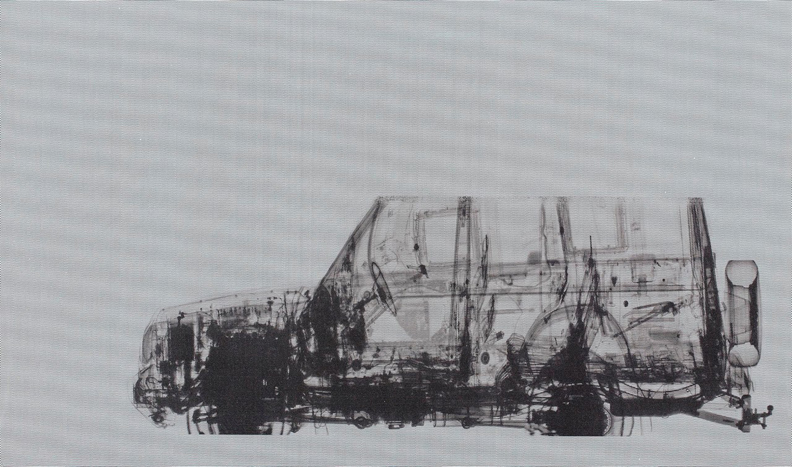

SUV-Mesh, 2010, Archival digital print on vinyl mesh, 28” x 47

All images in this interview courtesy of the artist

Bertha Husband: Before we discuss the works in your exhibition, Blazo, could you say a little bit about your background? I know you were born in Montenegro.

Blazo Kovacevic: Yes. I was born in 1973 in Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro. At that time it was called, ‘Titograd.’ After Tito’s death, it reverted to its original name. I went to art school in Cetinje, which is a very ancient and very quiet city, with few distractions.

BH: And you studied painting there?

BK: Yes. And it was very tough to get into the painting program. They generally only accept five painters a year. We had to draw and paint for a week just to pass the entrance exam. It is so tough, that when you pass and get admitted, it is such an achievement that it feels as if you have already finished school and graduated!

BH: I’m curious. With that sort of background, how did you develop from traditional painting to working more conceptually, with computers? I mean, you don’t really paint much any more, do you?

BK: Well, I do paint. But I consider it important to have all the tools available, and the computer is a very powerful tool. But this technology came to me in the US, because back then, in Montenegro, we couldn’t afford computers. In 1998, I applied and was accepted into the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) MFA program, at the same time as I was drafted, and if I hadn’t been accepted at PAFA, I would have ended up fighting Americans and Albanians in the Kosovo conflict. Instead, I watched it on CNN. It was at PAFA that I started doing more conceptual things, when I was exposed to the work of my professor, Osvaldo Romberg. He helped me liberate myself and to realize that everything is possible. That is very important, because you can get isolated if you are not exposed to other things – or don’t seek new exposures because you believe in the notion that you are what you are, and you can’t be anything else.

BH: But sometimes, it seems to me that art schools set out to destroy the student’s unique way of looking and try to remake them ….

BK: …in compliance.

BH: Yes. In compliance with the current art world fashion. It can be a destructive process for some people.

BK: I don’t know. I think artists have to be open to all other influences. Not to accept them, per se, but to be open. Openness is very important for my work because I get provoked by events – and then I do some work based on that.

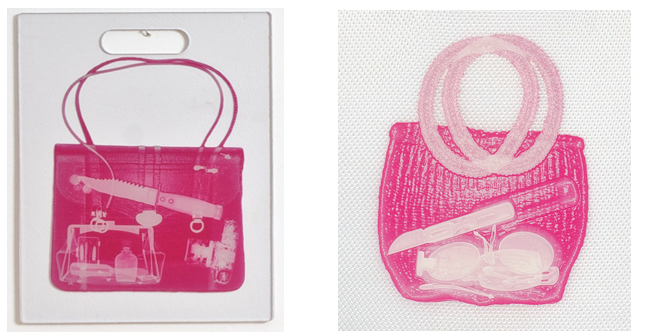

Pink Hand Bag, 2010, Digital print on polycarbonate, 25”x31”

BH: What would you say provoked you into working with the security x-ray images that have resulted in the ‘Probe’ works?

BK: It was just life, I guess. I was traveling more than I would have believed possible – mostly to go back home and see family, and for some residencies in Paris. This was more than I like, because I am afraid of planes. The security restrictions that were introduced after 9/11 hit us particularly hard because as foreigners from a country still perceived as a war-zone, you can imagine how carefully they were searching us. For example, I would always be put on one side for ‘random’ security checks. At first, I felt, ‘How lucky am I, to be ‘randomized’ so often!’ Then, I noticed that there was nothing ‘random’ about it. The only thing random is the word, ‘random.’ I have always been attracted and terrified by the crossing of a line, even the entrance to a theatre. By crossing a borderline, you become at the mercy of someone or some other force. I was never upset about how I was treated. What was really a problem was, ‘Why me?’ And once you are on their ‘List,’ whatever you do, you cannot get yourself removed from it. And my infant son, although an American citizen, was immediately subjected to the search because he was with me. The blindness of this action led me to the imagery of the x-ray machines.

BH: So you’ve actually been through those body x-ray machines?

BK: Actually, no. Because they haven’t had them at the checkpoints where I’ve been. But the baggage x-rays are everywhere, and I was first attracted to those images and then, just by researching, I came across this body scanner pilot program. It’s quite new and not widespread yet in the US, though now it is beginning to spread really fast.

BH: So, basically, you found the body scanner images on the internet?

BK: Yes, I found them on the internet and the images are amazing. They show the body stripped of everything. You don’t even see the body as male or female. You just see the body. You don’t see bones and organs and you don’t see features and you don’t see the hair. They’re almost like manikins. For me it was a really interesting form of figurative art. They’re not naked in a sexy way, but in a stripped down way, where everything not necessary is removed. It is, I think, in the artist’s nature to be a little voyeuristic. Artists are always interested in probing to see what is beneath the surface.

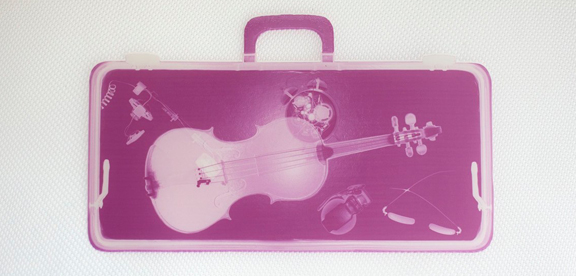

BH: Perhaps you could say something about how these works were made, and the use of color.

BK: The photographic images have been applied to canvas using an acrylic transfer technique. The colors are used straight from the tube. I don’t mix any paint. I don’t believe in color theory. I don’t know, it’s just …

BH: Color used as codes perhaps?

BK: Yes. An x-ray is black and white or a scale of grey, and with this baggage x-ray machine, the different values of grey are coded with different colors. Because the operator needs to see – very quickly – if there is something suspicious there.

BH: So the machine actually shows certain objects in a color?

BK: Yes. First it captures grey, and then different densities of material – metals, cloth, liquids, for example – translate into separate values of grey. And then there is a software program in the machine that assigns a color code to those values of grey that may indicate a danger. It is coded, as everything military is coded. And for my purpose, the color must stand out and I like to use new colors – the paint manufacturers have come out with a new oxide.

BH: Oh, yes. They now have all these metallic colors.

BK: Like iridescent or stainless steel. I mean if a paint is called ‘stainless steel’, that is something I will buy, rather than an ages old color like burnt umber. Thank God we have this paint industry, otherwise we would have to produce our own paints.

Blue Violin Case, 2010, Digital print on polycarbonate, 25”x47”

BH: We would be grinding colors extracted from the earth.

BK: It is interesting because now you can have a traditional painter who is using paint made by a new technology that would not be possible without computers. On the other hand, I really don’t think there is any merit in deciding, ‘I’m just going to be a painter’ or ‘I’m just going to be a conceptual artist.’ I think the only smart way is to be all that is possible.

BH: In fact your ‘Probe’ project is in two parts: the painted images that we see here and the conceptual part that is not yet realized.

BK: I first made a few of these works on canvas because I wanted to get peoples reaction to the images. I showed them to Stuart Horodner, curator at The Atlanta Contemporary Arts Center and he liked the idea and encouraged me to work more in that direction. It was then that I came up with a simple concept. I wanted to rent one of these body scanning machines and to place it at the entrance of the gallery. I wanted people to enter the show – that at that point wouldn’t exist – by passing through the machine as if they were at the airport. And if they gave permission, they would have their bodies scanned and we would print the images on magnetized paper and put them on the walls immediately. In this way the exhibition is generated by the audience. I can’t actually get my hands on one of these machines easily, but I haven’t given up the idea.

BH: It occurs to me that in order to work in this way, you would need to have a lot of money.

BK: Or just accept failure. Which is my situation so far. Some projects, of course, become realized, but there are key projects like this that I can’t do because either the technology isn’t ready, or I’m not ready, or I don’t have funding for it.

BH: You have mentioned another idea involving baggage scans.

BK: If you start with a grandiose idea like the one I just mentioned, you soon have to compromise. Right now, I’m working on the compromise version. I’m thinking of attaching the baggage scanning machines at the airport to the internet and having a live feed to the gallery. In this way, I would have a clear picture of peoples’ belongings and a moment when the passengers’ stress is transferred to pleasure.

Pink Handbag, 2010, 16”x13”, Digital print on Lexan (left); Pink Purse, 2010, Digital print on polycarbonate, 25”x22”(right)

BH: Yes. That’s what I like about these ideas – a technology that is used for security and defense is converted into something playful.

BK: It’s one event, but differently perceived. And that is a contradiction that I like, and seems always to be present in my work. It is actually possible to do this project in Montenegro, because it is a small country and everybody knows everybody. The President lives on my street and the Chief of Airport Security is my neighbor. So everything is possible, not for money, but just as a favor. And favor is a currency that never loses value. I like that about Montenegro.

BH: Would you prefer to live there?

BK: Yes, but also I like to live here. Actually I live there and here – but most of the time it is in the airplane between the two I feel most like myself. When you leave home you are frozen in the time when you left. People and things back there are changing, but you remain disconnected; and over here you are always a newcomer. So, however much I might fear flying, I think the plane is actually the perfect place for me.

BH: Well then we will leave you there, Blazo. Thanks for talking to me.

Blazo Kovacevic (b. Podgorica, Montenegro 1973), resides in Savannah, Georgia). He earned a B.F.A. in studio art from the University of Montenegro in 1997, and a M.F.A. in painting from the Pennsylvania Academy of The Fine Arts in 2000. Noteworthy solo exhibitions include: Probe, Nova Gallery, Belgrade, Serbia and Atelier Dado, National Museum of Montenegro, Cetinje, Montenegro; Maps and Cuts, Hurong Lou Gallery, Philadelphia, PA; Continental Breakfast, Gallery Chaos, Belgrade, Serbia; Liquidation, Cultural Center of Serbia and Montenegro, Paris, France; Clearance, Gallery Siano, Philadelphia, PA. Significant group exhibitions include: Impact, Swing Space Gallery, Ohio State University, OH; SUTRA Festival of Science, Belgrade Serbia, Why Go Anywhere Else?, Center for Contemporary Art of Montenegro, Podgorica, Modern Gallery, Budva, Josip-Bepo Benkovic Gallery, Herceg Novi and Kod Homena Gallery, Kotor, the Utopia Station at the 50th Venice Biennial, Italy amongst others. His work has been reviewed in the following media sources in Serbia, Montenegro, France and the United States: Art Centrala, Art Fama, Outlet, Art Newspaper, Modern Painter, Artension, Der Standard, Glas Crnogoraca, House Style, Likovni Zivot, Monitor, Nasa Borba, Novosti, Philadelphia Weekly, Pobjeda, Politika, Publika, Vijesti, TV RTCG, RTS and B92. He has been a member of the Association of Fine Artists of Montenegro since 1997. http://www.blazokovacevic.com/Probe/About.html

Bertha Husband is a painter and a founding member of Axe Street Arena, Chicago (1985-1989). Her critical reviews have appeared in several publications including the Chicago Reader and Art Papers.