Chris Revelle

On December 21st 1989, a day after the United States invaded Panama, three networks, ABC, CBS, and CNN, all broadcasted the same split-screen images. On one side of the screen, the somber ceremony taking place at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware as the first flag-draped coffins of American casualties were returned home. On the other side, President George H. W. Bush made jokes and laughed with the media correspondents at his first press conference since the invasion. The broadcast triggered a heated reaction from the public and media. [1] Despite the United States easily overwhelming the Panama Defense Forces, the American public turned its focus towards the U.S. casualties rather then winning the war. [2]

Unknown Author, US war casualties in a C-17 Globemaster II at Dover Air Force Base, Unknown Date, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/USCasualtiesC130DoverAFB.jpg

The public response was not forgotten by the Bush administration as the country once again prepared for an invasion and war with Iraq in 1990. As Operation Desert Storm began on January 16th, 1991, the Department of Defense issued a ban on February 2nd that “prohibit[ed] media coverage, including photographs, of public soldiers’ remains when they are returned to the United States.” [3] The ban and similar bans since have come to be known as the Dover Bans. Yet these bans are part of a long history of censorship and control over images and videos of war.

Jacques Callot, The miseries of war; No. 11, “The Hanging”, 1632, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Callothanging.jpg/800px-Callothanging.jpg

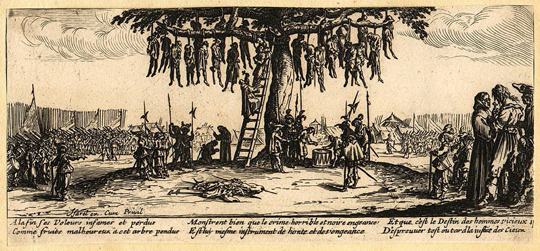

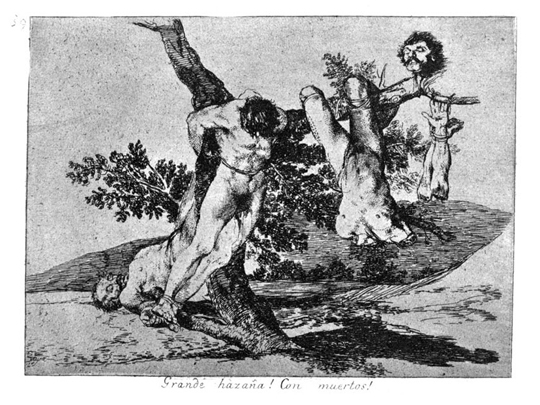

It has always been a struggle to capture war through images, attempting to explain its horror and violence without the experience. Before photographs and photojournalism, some artists took the responsibility to show the atrocities of war. Jacques Callot, a baroque printmaker, published a series of etchings entitled Les Misères De La Guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War). The etchings documented the French invasion and occupation of Lorraine (now part of France) during the 1630s. From 1810 to 1820 Francisco Goya, the court painter to the Spanish Crown, created a series of etchings Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), depicting the violence of the Peninsula War in which the Spanish revolted against French occupation. The etchings were kept private and never printed until 35 years after his death, at a time when the works were “less likely to offend.” [4] Goya’s etchings are divided into three sequential events—war, famine, and the return of Fernando VII and the Spanish Inquisition to power. The group of etched plates depicts women and children executed, girls raped, slaughters with piles of bodies, and desecrated and mutilated bodies as well as the despair of a famine that followed. [5] Susan Sontag writes in the book Regarding the Pain of Others, “The ghoulish cruelties in The Disasters of War are meant to awaken, shock, wound, the viewer . . . With Goya, a new standard for responsiveness to suffering enters art . . . The account of war’s cruelties is fashioned as an assault on the sensibility of the viewer.” [6] Sontag argues that though works like Goya’s, and other drawings and paintings, are “made” while photographs are “taken,” the photographer still decides what to frame—what to include and exclude. But photographs, unlike handmade images, can act as evidence. [7]

Francisco Goya, Los Desatres de la Guerra, Plate 39, Grande hazaña! Con muertos! (Great deeds! Against the dead!), 1810, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Goya-Guerra_%2839%29.jpg/800px-Goya-Guerra_%2839%29.jpg

Because of this, war images are often controlled and used to show the evidence of patriotism and sacrifice for the good of the nation. In 1853, the Crimean War began as the European Powers sought control over territories of the weakening Ottoman Empire. Roger Fenton, a well-known British photographer, was sent to the frontlines as the first war photographer, making the Crimean War the first war to ever be photographed. Fenton, funded and employed by the British War Office, was given the task of drumming up popularity for the war, which was dragging on and accumulating a massive British death toll. Fenton, as requested by the War Office, staged a collection of photographs portraying the war as a “dignified all-male group outing,” devoid of any pain or death. [8] Repeatedly showing the victories and successes of the happy and upbeat British troops far from the battlefield. These images were used to mislead the public by “distorting the real facts of the events.” [9]

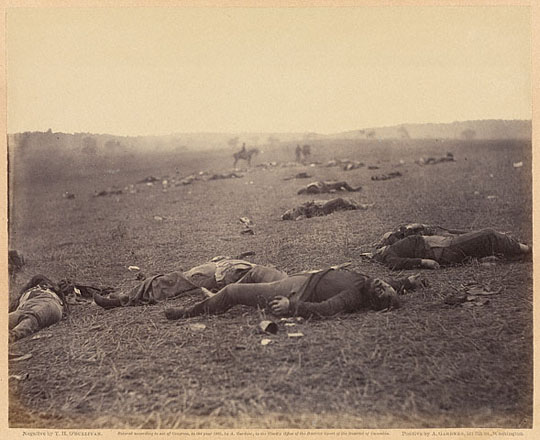

Despite the distortion of the first war photography, the American Civil War was documented with the intent to display the horror of blood soaked fields and the faces of the dead. The war was documented by a group of photographers organized by Mathew Brady, a photographer best known for his portraits of President Abraham Lincoln. Brady was given access to battlefields by President Lincoln but was not commissioned as Fenton had been by the British. The photographs, majority of them taken by Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, confronted audiences with distorted and twisted bodies of Union and Confederate soldiers. Once again Susan Sontag explains, “The first justification for the brutally legible pictures of dead soldiers, which clearly violated a taboo, was the simple duty to record. ‘The camera is the eye of history’ Brady is supposed to have said . . . In the name of realism, one was permitted—required—to show unpleasant, hard facts.” [10] Though the photographs illustrated war in a completely new way, the images still had similarities with the photographs of Crimean War and the images of wars to come; they were staged.

Timothy O’Sullivan, A Harvest of Death, 1863, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/86/Timothy_H._O%27Sullivan_-_A_Harvest_of_Death.jpg

Brady’s photographers arranged the scenes that they photographed, moving bodies into more aesthetic scenery. This practice of staging images continued throughout the World Wars to produce desired responses. The famous Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima photograph taken on February 23rd, 1945, by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal, depicted five U.S. Marines and a U.S. Navy corpsman raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. Associated Press describes the influential photograph,

It has been called the greatest photograph of all time. It may well be the most widely reproduced. It served as the symbol for the Seventh War Loan Drive [during World War II], for which it was plastered on 3.5 million posters. It was used on a postage stamp and on the cover of countless magazines and newspapers. It served as the model for the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Va., a symbol forever of the valor and sacrifices of the U.S. Marines. [11]

And though Rosenthal still remains firm that the raising was not posed, the photograph did not capture the first American flag to be raised on Mount Suribachi that day. Associated Press explains, “The fact is that neither set of flag-raisers encountered serious resistance from the Japanese as they scaled Mount Suribachi that day. And in retrospect, the scaling of Mount Suribachi was not the great turning point in the battle that it may have seemed: The fighting at Iwo Jima continued for 31 more days.” [12] In the end, 6,821 Americans died, 5,931 of them U.S. Marines, nearly one-third of all Marine casualties during the war. Of the 21,000 Japanese soldiers stationed on the island, only 1,000 survived. [13]

(From Left to Right)

US Post Office, Battle of Iwo Jima, 1945, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/3c-Iwo_Jima.jpg/411px-3c-Iwo_Jima.jpg.

Department of the Treasury, Now All Together, 1945, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/76/7WarLoan.jpg/423px-7WarLoan.jpg.

Felix de Weldon (Artist), Tiffini M. Jones (Photographer), Marine Corps War Memorial, Arlington, VA, 1954, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia

/commonsavy_071110N8273J126_U.S._Marines_conduct_a_wreath_laying_ceremony_in_honor_of_the_232nd_Marine_Corps_birthday_at_the_Marine_Corps_War_Memorial.jpg

Even today, “journalism’s images become a key tool for interpreting the war in ways consonant with long-standing understandings about how war is supposed to be waged—notions about patriotism, sacrifice, humanity, the nation-state, and fairness,” says Barbie Zelizer, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. [14] In the lead up to Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, the average budget for war coverage by major networks was $23 to $30 million. [15] While newspapers traditionally publish more photographs and print them larger during wartime, the New York Times more than doubled the number of photographs in the paper during the first year of the Iraq War. Often the photographs published serve “patriotic and not journalistic purposes” and become “tools of public consensus that [facilitate] U.S. military and political ends.” [16] The images of war rarely show the true face of its brutality, and more often are used to “mask the darkness of death.” [17]

The images of heroism and patriotism do not come only from photojournalism and the frontlines. The public is consistently saturated with pro-military recruitment messages and advertisements from television commercials and NASCAR to video games and blockbuster movies. Commercials about “Army Strong” and “The Few, The Proud” are meant to remind of the sacrifice given by generations before. Yet the images do not display the price the previous generations paid or what they experienced. When images of fighting and battle are used within the advertisements it is theatrical with a clear sense of good and evil, such as the U.S. Marines commercial with a finale between a Marine armed with a sword and a dragon made of fire. The Department of Defense (referred to as the DoD or the Pentagon, and formerly the War Department until 1947) floods the public with a variety of campaigns with the latest technology and spends more on recruitment advertising then any other corporation, including Coca-Cola, Nike, and Wal-Mart. [18]

The DoD currently employs “27,000 people just for recruitment, advertising and public relations — almost as many as the total 30,000-person work force in the State Department.” [19] The current staffing cost for this force is $2.1 billion, with $1.6 billion going for advertisement and recruitment, $547 million for public relations, and another $489 million into what is known as “psychological operations” that is directed at foreign audiences, totaling over $4.7 billion annually. [20]

William Thurmond, U.S. Army Top Fuel, 2006, Public Domain

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/75/Tony_Schumacher_CSA-2006-09-26-090353.jpg and http://web.archive.org/web/20070701032555/http://www4.army.mil/armyimages/armyimage.php?photo=11513,

The billions of dollars for recruitment and advertising are used to create a strong public image and brand recognition for each of the military branches. Today the Army, Air Force, Marines, Navy, Amy National Guard/Air Reserve, Marine Corps Military Reserve, and Air National Guard/Air Force Reserve all have NASCAR teams, at a cost of $38 million in 2005. [21] The U.S. Army also uses a flame throwing black and yellow dragster and a “tricked out” humvee (High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle) with custom paint and interior, and an entertainment system with a DVD player and massive speakers to grab attention. In addition to sponsoring a range of sporting events, the Pentagon offers an assortment of websites for all military branches on the Internet where visiters can download screen savers, read comic books, play games, order free t-shirts, watch the latest commercials, and join online chat rooms with live recruiters. The video game has become one of the most popular features as well as one of the most controversial.

America’s Army (AA) is the U.S. Army’s own first person shooter video game. The game, which was first released on July 4th 2002, is free to download and for pick up at recruitment centers, and is available at arcades and for PC, X-Box, or Playstation. The training and combat game is one of the top five most popular online games, [22] and has over 10 million registered players. [23] Criticized for using a toy to interest older children and younger teenagers, America’s Army turns real life horror into a virtual experience. The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) has rated the game safe for teens, saying, “Titles rated T (Teen) have content that may be suitable for ages 13 and older. Titles in this category may contain violence . . . [and] minimal blood.” [24] In an attempt to bring the reality of war to the video game, artist Joseph DeLappe began a virtual final roll call in March 2004, the first anniversary of the Iraq War, for the soldiers who have lost their lives in Iraq. While players continue to fight, DeLappe, using the call sign “dead-in-Iraq”, does nothing except type the names of the soldiers who have died in Iraq into the game’s chat interface. [25] Despite DeLappe’s “annoying” performance, the video game has continued to grow in popularity and has been called a 21st century “I Want You” poster. [26] But the video game and influential “I Want You for the U.S. Army” poster are much more than recruiting tools, they are part of a long history of war propaganda within the United States.

James Montgomery Flagg, I want you for U.S. Army, 1917, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7e/I_want_you_for_U.S._Army_3b48465u_original.jpg

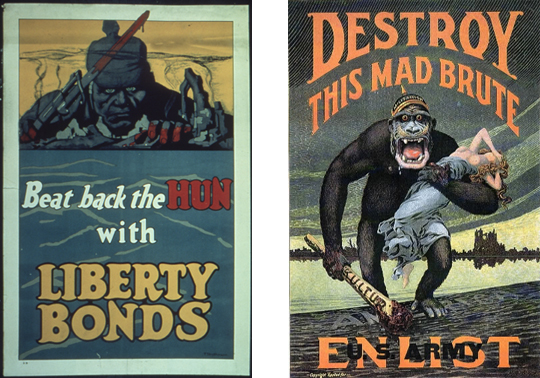

In 1917, Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI); also known as the Creel Commission after George Creel, a government agency employing 150,000 people, created to “engineer consent” for the United State’s intervention in the Great War (the Great War only became World War I after the start of World War II). The CPI’s goal was, “the creation of a ‘war will’ among an ethnically diverse American population, according to its chief George Creel. Abroad, its purpose was to convince publics that America, reliable, honest and invincible, would defeat German militarism and make the world safe for democracy.” [27]

(From Left to Right)

Fred Strothmann/Committee On Public Information, Beat back the Hun, 1918, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/%22Beat_back_the_HUN_with_LIBERTY_BONDS.%22_-_NARA_-_512638.tif/lossy-page1-399px-%22Beat_back_the_HUN_with_LIBERTY_BONDS.%22_-_NARA_-_512638.tif.jpg

H.R. Hopps/Committee On Public Information, Destroy This Mad Brute, 1917, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/%27Destroy_this_mad_brute%27_WWI_propaganda_poster_%28US_version%29.jpg

The committee used nearly the same media venues that the public sees today, newspapers, books, posters, radio, and movies, which became the “blueprint in which marketing strategies for future wars would be based upon” and the foundation for the public relations industry. [28] The CPI also organized and created the Committee of Pictorial Publicity, who employed among other famous illustrators James Montgomery Flagg. Flagg contributed over 46 posters to U.S. war efforts, but his most famous was the portrait of Uncle Sam in the “I Want You for the U.S. Army” (1917), who some consider “the most famous poster in the world.” The poster was used again during World War II because of its popularity and is still displayed at many Armed Forces Career Centers (recruitment centers). [29]

The CPI was also able to enlist the support of Hollywood to build support for the war. As author J. Michael Sproule explains,

As a result of the Creel committee’s liaison with the commercial movie studios, leading directors such as [Academy-Award winning] D.W. Griffith [The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916)] and major producers such as Carl Laemmle [founder of Universal] helped rally the new medium of film to Wilson’s cause. Griffith’s tour de force wartime picture was Hearts of the World, built around scenes of dissolute German troops molesting property and persons in an occupied French village. Laemmle’s The Kaiser, The Beast of Berlin, a movie whose title renders superfluous its producer’s admission that the picture was “a conscious form of propaganda,” similarly prompted excited responses from wartime patrons. [30]

In addition to producers and directors, these films even received the help of Hollywood stars like Charlie Chaplin. [31]

Since their early success, the United States has consistently used Hollywood to promote war and a positive image of the military. Today, every branch of the military has a Los Angeles office to work with and supervise filmmakers and studios. [32] One of the producers for the movie Transformers (2007), Ian Bryce, described the relationship as a “win-win situation.” Bryce went on to say, “We want to cooperate with the Pentagon to show them off in the most positive light, the Pentagon likewise wants to give us the resources to be able to do that.” [33] The DoD has been apart of some of the biggest blockbusters since the early 20th century. Some of the more recent movies include, Top Gun, True Lies, Executive Decision, Black Hawk Down, Pearl Harbor, Behind Enemy Lines, Iron Man, and Transformers 2. These films received full support of the Defense Department, including military extras, latest weaponry and fighter planes, and access to U.S. military bases. [34] Though not every film that applies receives the Pentagon’s full support. Apocalypse Now, G.I. Jane, [35] and A Few Good Men were all denied access to DoD assistance and support because the films did not show U.S. forces as moral and heroic. [36]

The Defense Department does not limit its assistance only to the Hollywood studios for its self-image. Since World War I non-military journalists have been given broad access to the frontlines of war, but were forced to accept censorship in return. The Pentagon maintained strict control over war reporting until the Vietnam War when television technology began to play more of a major role in the reporting. [37] The Museum of Broadcast Communications explains the difference,

Vietnam was the first “television war.” . . . The first “living-room war,” as Michael Arlen called it. . . It brought the “horror of war” night after night into people’s living rooms and eventually inspired revulsion and exhaustion. The argument has often been made that any war reported in an unrestricted way by television would eventually lose public support . . . In August 1965, . . . CBS aired a report by Morley Safer which showed Marines lighting the thatched roofs of the village of Cam Ne with Zippo lighters, and included critical commentary on the treatment of the villagers. This story could never have passed the censorship of World War II or Korea, and it generated an angry reaction from [US President] Lyndon Johnson. [38]

Susan Sontag argues that because of the television war, photojournalists had to adapt and compete with the nightly images. [39] Out of these brutally honest and gruesome photographs, there has been one that has remained one the most vivid of the Vietnam War. It was U.S. Army photographer Ronald L. Haeberle, who captured a massacre in the small Vietnamese village of My Lai in which over 500 unarmed civilians were killed by U.S. Marines, majority of them women, children, and the elderly. [40] The photograph of a dirt road littered with fallen bodies, including babies, was published in Life magazine in 1969. The release of the image became the turning point for public sentiment against the war. Professor and author Camilla Griggers describes the events,

The Army photographer, Ronald Haeberle, assigned to Charlie Company on March 16, 1968 had two cameras. One was an Army standard; one was his personal camera. The film on the Army owned camera, i.e., the official camera of the State, showed standard operations that is “authorized” and “official” operations including interrogating villagers and burning “insurgent” huts . . . Haeberle’s personal images (owned by himself and not the US Government) showed hundreds of villagers who had been killed by U.S. troops. More significantly, they showed that the dead were primarily women and children, including infants. These photographs exposed the fact that the “insurgents” in popular discourse about Vietnam were actually unarmed civilians. The photos made visible to viewers that the “enemy” in Vietnam was actually indigenous Vietnamese population. [41]

Ronald Haeberle, My Lai Massacre, 1968, Public domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/77/My_Lai_massacre.jpg and http://www.krysstal.com/democracy_vietnam_mylai.html

Peter Brandt and the Art Workers’ Coalition later made the photograph into a protest poster. The poster used the original image by Haeberle along with a short quote from an interview with Pvt. Paul Meadlo, one of the U.S. Marines who took part in the My Lai Massacre, with journalist Mike Wallace as transcribed by the New York Times: “Q. And babies? A. And babies.” in translucent blood red text. [42]

The relationship between the U.S. government and journalists changed dramatically following Vietnam. Author Bill Katovsky describes the differences that followed, “When U.S. military forces stormed Grenada in 1983, navy gunboats kept the press away from the island. Six years later, the Panama invasion was hardly more accommodating to journalists, who were either left stranded on airport tarmacs in Miami and San Jose, Costa Rica, or sequestered in a Panama City warehouse throughout most of the fighting.” [43] At the start of the Persian Gulf War in 1991, networks were pleading for access but by then the Defense Department had a dramatically new strategy for war and for the press.

The Gulf War, as Tom Brokaw stated, “[was fought] at arm’s length with long-range missiles [and] high-tech weapons.” [44] “The unstated but obvious truth was that by carrying out an air war that was unprecedented in its ferocity, U.S. strategy sought to reduce U.S. military losses at the expense of thousands of Iraqi civilian casualties,” Jim Naureckas wrote in his critique of the media coverage for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. The change in strategy and weaponry greatly affected the images of war the public received. Though the media was cut off from the frontline, it was given full access to the videos from the camera-equipped high-tech weaponry. The use of the videos gave the impression of precision and absolute accuracy of the missiles. The British journalist Patrick Cockburn contradicted this claim in the London Independent,

From the beginning, the allies’ bombs and missiles were never as accurate as might have appeared . . . There were craters where missiles had hit houses or waste ground, or were far from any obvious targets . . . The allied air forces have become victims of their own propaganda. They have pretended they can carry out surgical strikes; but mass bombing remains a blunt instrument. [45]

The press was kept at an even further length than the fighting, and without more journalists on the ground to verify the statements by the DoD, the images of perfectly dropped bombs had the final word. When reports and images did surface of civilian casualties after the massive bombings, they were dismissed as propaganda or as Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s fault. These claims and other pro-war analysis were backed by a “one-sided procession of retired military brass, ex-government hawks, right-wing pundits and politicians.” [46] The Museum of Broadcast Communications wrote,

In the aftermath of [the Gulf War], television and other media were criticized for having failed to provide a balanced and complete account of the war. Some critics, most notably Douglass Kellner in The Persian Gulf TV War, argue that television and other media failed to provide a balanced and complete account of the war because the corporate owners of commercial networks felt it was not in their business interest to do so. Other critics suggest that television coverage simply reflects popular prejudices. To a great extent, however, during the actual war, as in previous wars, the various national media had to rely on the military forces for access to events and for access to their broadcast networks. [47]

Department of Defense, Gulf War Target Camera Image, 1990-91, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/57/Gulf_war_target_cam.jpg

The Pentagon’s strategy during the Gulf War of using mass bombings to achieve quick political and military gain without the pressure from the media or the lose of American soldiers was so effective it came to be known as cruise missile diplomacy, referring to the tomahawk cruise missile and gunboat diplomacy of the past centuries. [48] The cruise missile replaced media access and “presented the war visually with dramatic techno-images . . . [with] videos of hi-tech precision bombing and the aerial war over Baghdad.” The Pentagon released a constant stream of videos from the cameras of cruise missiles and other smart bombs, “which were replayed repeatedly, similar to replays of heroics in a sports event.” [49]

Following the Persian Gulf War and the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the Pentagon was heavily pressured to give greater access to reporters. As the Pentagon and media both prepared for the 2003 Iraq War, over 2,700 reporters, photographers, and television and radio crews received media credentials from the DoD, [50] including 700 “embedded” journalists. [51] Operation Iraqi Freedom began in March 2003 with a massive shock and awe bombing campaign and ground invasion, and the media, for the first time since Vietnam, had unprecedented access to the frontline in the form of embedded journalists, or embeds. Journalists, who “embedded” with a group of soldiers, lived, slept, ate, and traveled with them. The journalists had complete access to the soldiers, their missions, and what they saw and experienced. Todd Gitlin, a professor of Journalism and Sociology at Columbia University, observed, “Embeddedness has a built-in swerve toward propaganda . . . because an embedded reporter is on the team. A reporter shares the risk and is dependent on the soldiers he is traveling with for his [or her] very life. The desire to write negative stories about them is quite diminished.” The same could be said about the images they capture and present.

Despite the pressure to report positive stories about the soldiers who are protecting their life, few journalists still managed to write about what they saw and heard without influence. Once again Bill Katovsky from his book Embedded,

Correspondents still found moments of truth and poignancy, even while failing to account for mounting civilian deaths or aggressively challenge the White House’s pretext about making Iraq the second front on the war of terror. Some of the best reporting defied whatever spin the Pentagon tried to achieve when deadly mistakes were made on the battlefield, because an embedded journalist was there taking notes. Nor could the military muzzle its soldiers who spoke openly around embeds. Perhaps the most unforgettable quote of the war was overheard by The New York Times’ Dexter Kilkins who cited two Marine sharpshooter comparing notes about the difficulties they encountered trying to distinguish civilians from fighters: “We dropped a few civilians but what do you do? I’m sorry, but the chick was in the way.” [52]

Many journalists became “disembedded”, or removed from Iraq with military assistance, for writing what the Pentagon deemed negative while giving the convenient excuse of reporters breaking military rules and regulations. Unembdded journalists were also subject to removal from Iraq. Some reporters were even detained for days or even years. [53] Sami Al-Hajj, a cameraman for the Arabic and English Satellite News Network Al Jazeera, was arrested on the border of Afghanistan in Pakistan in December of 2001 during coverage of the media-restricted U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. Al-Hajj was moved to multiple detention centers in Afghanistan and Pakistan before finally being taken to the U.S. base and prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Al-Hajj spent over 6 years and 7 months at the prison for what the U.S. government describes as an “error.” [54]

Al Jazeera has repeatedly come under criticism and under fire by the U.S. government for broadcasting images of dead soldiers and civilians, reporting from beyond battle lines, and messages from head Al Qaeda members such as Osama bin Laden. Two U.S. “smart” bombs hit the station’s headquarters in Kabul, Afghanistan in April 2002. [55] In April 2004, Al Jazeera’s office in Baghdad, Iraq was struck by a missile killing one of the station’s correspondent and wounding another member of its staff. [56] Former U.S. President George W. Bush even discussed bombing the station’s headquarters located in Doha, Qatar, with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2005, which was ultimately ruled out. [57]

It is becoming increasingly dangerous to report or capture images of war. In 2008, 95 journalists in 32 countries died for the information and images they were reporting. The 2008 Press Emblem Campaign (PEC) Report begins with, “On average, nearly two journalists were killed every week in the course of the last three years (96 in 2006; 115 in 2007; 95 in 2008). Many others were injured, kidnapped, threatened, imprisoned or unable to express themselves freely (notably in Burma, China, Zimbabwe and Eritrea).” [58] The International Federation of Journalists begins its 2008 report with, “Across the world journalists and media continue to be in the firing line. From poverty and tribal rivalry in central Africa, to drug wars on the United States border with Mexico, civil strife in Sri Lanka, the never-ending tragedy of Palestine and continuing clashes of culture and politics in Iraq, the uncertainties of unresolved borders between India and Pakistan and rapidly-warming frozen conflicts around the former Soviet Union, all provide stories laced with danger and threats.” [59] Iraq has become and remains the most deadly place for journalists. Since the beginning of the war in 2003, over 265 have lost their lives in the pursuit of reporting war. Many of the murders go unreported in international media because the journalists are Iraqi nationals. [60] The PEC concludes, “The great majority of journalists killed were personally targeted because of their profession. There were deliberate killings aiming to eliminate individuals owing to their investigations or opinions running counter to those of armed groups, political groups criminal networks or local interests.” [61]

As Former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney stated in 1991, “I don’t look on the press as an asset. Frankly, I looked on it as a problem to be managed.” [62] And the Pentagon has made it clear what it prefers to hear and see from the battlefields, and which networks and reporters best deliver that message and point and view. In a recent investigative report by Stars and Stripes, an independent newspaper for the military community, the Pentagon was exposed as having screened and profiled reporters who applied as embedded journalists in Iraq and Afghanistan. Stars and Stripes recently obtained documents and reports from the Rendon Group, a Pentagon contractor, that show reporters were being graded as “positive,” “neutral,” or “negative.” The paper writes,

Moreover, the documents — recent confidential profiles of the work of individual reporters prepared by a Pentagon contractor — indicate that the ratings are intended to help Pentagon image-makers manipulate the types of stories that reporters produce while they are embedded with U.S. troops in Afghanistan. One reporter on the staff of one of America’s pre-eminent newspapers is rated in a Pentagon report as ‘neutral to positive’ in his coverage of the U.S. military. Any negative stories he writes ‘could possibly be neutralized’ by feeding him mitigating quotes from military officials.” [63]

The Pentagon and Rendon Group both responded to the report with outrage and denial, but after weeks of reports by Stars and Stripes and a wave of outraged responses, the contract between the two was terminated at the end of August 2009. [64]

Embeds often go through extremes to stay on the frontlines to get their report, but no matter how well they write or how alarming the story might be, pictures are still how wars are remembered. Unfortunately the photographs and images shown during war rarely depict the frightening truth of it. Author and professor Barbie Zelizer explains,

The fact that in times of war, journalism shifts to . . . pictures of the memorable, frequent, dramatic, aesthetically appealing, powerful, and familiar over the newsworthy, and it encourages pictures in a way that facilitates faulty comparisons across events . . . The public sees many pictures of war but what it sees is not necessarily what it needs to see. Seen are shards of wartime presented in a way that forces certain public responses and mutes questions . . . When war is reduced to a photograph, then, its usage depends on journalism being less journalistic than it needs to be. [65]

The images and photographs from the Iraq War are rooted in past propaganda. By striking parallels with previous wars and movements, the images are able to create quick emotional responses based on memory. One of the strongest examples of this is from the first weeks of the ground invasion, when a 40-feet statue of Saddam Hussein was toppled in Baghdad’s al-Firdos Square. The event sparked memories of revolutions and protest in Eastern Europe and was even linked to post Cold War events by the American cable and satellite news channel Fox News. “The enduring symbol of the day was surely the toppling of the towering Saddam statue, a gesture that recalled the frenzied euphoria that swept Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union more than a decade ago. Then, it was a statue of Lenin that came tumbling down,” Fox News reported the following day. [66] The immediate images and reports limit the understanding of the event. The square was actually closed off to the Iraqi public with U.S. forces only allowing in a few pro-American Iraqis, who waited until the U.S. troops, not Iraqis, pulled down the statue. [67]

When the public becomes saturated in these controlled images of “freedom” and “liberty,” it allows the U.S. government and Defense Department to operate with much more freedom and far less resistance and criticism. At the time of writing, the U.S. government is currently fighting an uphill battle to maintain support for the war in Afghanistan and is attempting to censor and criticize any images that might force a quicker end. On September 4th, 2009, the Associated Press (AP) distributed an image and report of Joshua Bernard, a young Marine, fatally wounded after being hit by a rocket propelled grenade in Afghanistan. AP stated that the image, “conveys the grimness of war and the sacrifice of young men and women fighting it,” and it was the responsibility of AP to “show the reality of the war there, however unpleasant and brutal that sometimes is.” [68] The Pentagon and Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, responded with condemnation and disgust, writing,

Why your organization would purposefully defy the [Bernard] family’s wishes knowing full well that it will lead to yet more anguish is beyond me. Your lack of compassion and common sense in choosing to put this image of their maimed and stricken child on the front page of multiple American newspapers is appalling. The issue here is not law, policy or constitutional right – but judgment and common decency.” [69]

The choice to call the Marine a child helps to insist his youth and innocence, making the image even more offensive. But on the other side, the Pentagon still deemed the child and other children to be old enough for combat and death. The photographer Julie Jacobson was quoted in the original article saying, “To ignore a moment like that simply … would have been wrong. I was recording his impending death, just as I had recorded his life moments before walking the point in the bazaar. Death is a part of life and most certainly a part of war. Isn’t that why we’re here? To document for now and for history the events of this war?” [70] However new technology is rapidly changing the events of war and the way it is fought, in hopes of removing soldiers from the battlefield as well as images of their suffering.

As you read this, there at least 35 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, hovering over Iraq and Afghanistan. By 2010, the U.S. Air Force will have at least 50 in the air at any one time. [71] Drones are remotely operated aircrafts used for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), as well as attack missions. Though the plane and ground crew remain in strategic locations throughout the Middle East and South Asia, the pilot that operates the drones is located over 7,500 miles (12,070 km) away linked by a satellite connection. Weighing only 1,130 pounds (512 kg) with the ability to fly for 24 hours and altitudes of 26,000 feet (nearly 8km), the Predator is one of the “most notable” drones. [72] Costing just under $4.5 million, the Predator is equipped with a synthetic-aperture and two variable-aperture TV cameras, giving the drone the ability to see through clouds, smoke, and dust as well as infrared vision during night. [73] The pilots fly and control the drones from air-conditioned trailers in Nellis and Creech Air Force Base just outside of Las Vegas, Nevada, as well as Arizona, California, North Dakota, and by 2010, New York. [74] Sitting behind a “1990s-style computer banks filled with screens, inside dimly lit trailers,” with an arcade style joystick, drone pilots supply over 16,000 hours of surveillance each month. [75]

Chris Revelle, YouTube War, Digital Video (Still) 46’ 39”, 2009-11, Photo Courtesy of the Artist.

Though the drones became operational during the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo, the massive demand for the Predator came “after the military turned to new counterinsurgency techniques in early 2007.” [76] But even before 2007, the Predator was already a major part of operations, flying 2,073 missions totaling 33,833 hours, and surveying 18,490 targets, just from June 2005 to June 2006. Though the Predator has been outfitted with Hellfire missiles, the Predator’s “cousin,” the Reaper, carries out most of the missile attacks. [77] The Reaper is “four times bigger and nine times more powerful,” as P.W. Singer author of Wired for War explains, “Not only can the plane come close to flying itself, but its sensors can also recognize and categorize humans and human-made objects. It can even make sense of the changes in the target it is watching, such as being able to interpret and retrace footprints.” [78] The increase of drones and drone pilots is unprecedented and more importantly, rapidly changing the course of war, as the Christian Science Monitor reports,

- The Air Force will train more officers on remote-controlled aircraft than combat fighters for the first time ever.

- Last month, the service’s prestigious weapons school graduated its first group of students who know more about munitions for unmanned aerial vehicles than they do weapons for fighter jets.

- And last month, the first group of officers with no formal Air Force pilot training graduated from an Air Force school. [79]

One reason for such a major change in resources is simply that the technology is helping to save U.S. soldiers’ lives, from hovering over a house raid and watching roads for IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devise) to tracking insurgents and launching attacks. The drones are taking soldiers off the battlefield, out of harm’s way, and consequently out of public concern. By removing U.S. soldiers from the frontlines, it dramatically changes the relationship and interest the public has invested into the war. The drones and other robotic systems are removing the sacrifice of soldiers. By removing the human cost of war and the images of soldiers returning home in coffins or their trauma on the frontlines, the Pentagon has made the decision to choose war over diplomacy even easier. Once again P.W. Singer explains, “Unmanned systems represent the ultimate break between the public and its military. With no draft, no need for congressional approval (the last formal declaration of war was in 1941), no tax or war bonds, and now the knowledge that the Americans at risk are mainly just American machines, the already lowering bars to war may hit the ground.” [80] Singer also argues that without public investment into the war, such as support for family members and friends fighting aboard, the public will no longer be concerned about the war. Singer quotes Larry Korb, a former navy flight officer and now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, “[Drones] will further disconnect the military from society. People are more likely to support the use of force as long as they view it as costless.” [81] Despite the problem that future wars and conflicts may be costless for only one side, there will be even less pressure put on the Pentagon and elected officials for better policy and diplomacy, and less war.

Just as new technology is changing the way the public interprets war, it is also changing the images of war. The images and videos beamed 7,500 miles away via military satellites are being uploaded and shown as entertainment. Much like the videos from cameras mounted on missiles during the Gulf War, drone videos transform the violence and destruction into sport highlight reels where the attack is the climax for viewers. The videos are already a part of the vast collection of videos and images of extreme brutality, violence, and humiliation known as “war porn.” As author P.W. Singer explains,

The Iraq war is literally the first war where you could download video of the combat off the Web; as of 2007, there were over seven thousand video clips of combat footage from Iraq on YouTube.com alone. Much of this footage was capture by various drones and unmanned sensors and then posted online. Some of the videos were official, but many were not . . . Inevitably, the ability to download the latest snippets of combat footage to home computers turn war into a sort of entertainment, or ‘war porn,’ . . . such as an insurgent blown up by a UAV . . . A typical example was a clip of people’s bodies being blown up into the air by a Predator strike set to Sugar Ray’s song ‘I Just Want to Fly.’ [82]

In 2004, French social theorist Jean Baudrillard first coined the term “war porn” after digital photographs exposed the brutal humiliation of Iraqi detainees by U.S. soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison, 20 miles west of Baghdad. [83] Many of the detainees “had been picked up in random military sweeps and at highway checkpoints”, [84] and of which 90 percent were innocent, according to Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, who was in charge of all military prisons in Iraq at the time. [85] Iraqi detainees were hooded and striped bare, paraded on dog leashes, bound in stress positions for hours, covered in human feces, forced to masturbate and have simulated sex, and piled into human pyramids. All of these acts and more were carried out and documented by a group of U.S. military prison soldiers, who grinned and posed for the shots. Because most of the pictures had a sexual theme with “crude aesthetics, and low production values, [and] even share[d] the look of modern porn,” the images were labeled as the pornography of war by Baudrillard. [86] The soldiers have since adopted the term and still take, upload, and trade videos and images of humiliated victims and horrific deaths.

Before it was war porn, images and videos taken by soldiers during war were known as trophy photos and videos. And even before video and photo trophies there were war trophies. Despite war trophies being illegal under military law, commanding officers allowed U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq to take rugs, silverware, and crystal from Saddam Hussein’s palaces, as well as Korans, which were classified by U.S. customs as a “piece of history.” Some of these items were even sold on eBay. [87] Erin Steuter and Deborah Wills explain the practice in their book At War With Metaphor,

For many years, soldiers in war have collected trophies of their military conquests, such as weapons, valuables, photos, ordnances, medals, and other keepsakes. Soldiers in many previous wars have taken photos of dead enemy soldiers and sent them home to family and friends with triumphant notes attached. Often these photos would be passed around from soldier to soldier like playing cards. By soldiers’ accounts, the commemorative taking of ears, fingers, even heads was not out of the ordinary. [88]

As reported in TomDispatch.com, a Vietnam veteran describes the human trophies collected by fellow soldiers in the book Bloods, An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans,

[Soldiers] would sometimes take the dog-tag chain and fill that up with ears . . . They would take the ear off to make sure the VC [Viet Cong] was dead . . . And to put some notches on they guns. If we were movin’ through the jungle, they’d just put the bloody ear on the chain and stick the ear in their pocket and keep going. Wouldn’t take time to dry it off. Then when we get back, they would nail ‘em up on the walls of our hootch. [89]

The practice is still carried on today with U.S. soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, with gruesome accounts of soldiers dragging the bodies of insurgents through the streets of Fallujah and “taking ‘trophies’ of brain matter from Iraqis they killed and putting such in their refrigerators on base.” [90]

Photo trophies in previous wars have been no less horrific. During the Boxer Rebellion or Boxer Uprising in China at the beginning of the 20th century, proud Europeans were photographed holding up decapitated Chinese heads as trophies. [91] From the 1880s to the 1930s American lynching mobs took photographs with mutilated and disfigured bodies of African American men and women hanging from trees. In the article Regarding the Torture of Others, Susan Sontag makes a clear connection between these photographs and the ones taken at Abu Ghraib, saying, “The lynching photographs were souvenirs of a collective action whose participants felt perfectly justified in what they have done. So are the pictures from Abu Ghraib.” [92] Sontag then goes onto argue the difference with the Abu Ghraib images is the change in technology, “A digital camera is a common possession among soldiers. Where once photographing war was the province of photojournalists, now the soldiers themselves are all photographers — recording their war, their fun, . . . their atrocities — and swapping images among themselves and e-mailing them around the globe . . . Today’s soldiers instead function like tourists.” [93] Where trophy photos in previous wars were to “memorialize” the moment and the experience, the availability and ease of digital cameras, cell phones, and computers has made them a documentation of the everyday.

Department of Defense, Abu Ghraib, Iraq, 2003, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/17/Abu_Ghraib_11a.jpg

When the news program CBS’s 60 Minutes II and investigative reporter Seymour Hersh in the New Yorker released these images and reports, the George W. Bush and his administration quickly condemned the photographs and the soldiers, calling them “a few bad apples.” [94] And though the photographs supposedly shocked the Bush administration, there had been at least two major reports detailing detainee abuse written and released before the media reports and photos were in late April 2004. The first and most revealing of the abuses at Abu Ghraib has become known as the Taguba Report. Written by Major General Antonio Taguba, the report investigated the conduct of the 800th Military Police Brigade at the prison. In the report Major General Taguba clearly explains the humiliation and abuse performed by the soldiers, and was supported by “written confessions provided by several of the suspects, written statements provided by detainees, and witness statements,” and states that many of the acts were videotaped and photographed. [95] In addition, the Major General also stated he believed that detainees had phosphoric liquid poured on them, were raped or threatened with rape, and were sodomized with a chemical light and a broomstick. [96] Every one of these acts are considered war crimes by the Geneva conventions of 1949 as well the 1984 Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, both of which the United States has signed and agreed to. As Susan Sontag points out, “Apparently it took the photographs to get their attention, when it became clear they could not be suppressed; it was the photographs that made all this ‘real’ . . . Up to then, there had been only words, which are easier to cover up in our age of infinite digital self-reproduction and self-dissemination, and so much easier to forget.” [97]

It is without these images that brutality, war, and even genocide is ignored and forgotten. Prasun Sonwalkar writes in the article Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The non-reporting of small wars and insurgencies, “For every conflict that is well covered or analyzed, there are countless that remain unreported, ignored, or marginalized.” Sonwalkar continues, “Wars and conflicts are not intrinsically newsworthy; they need to be culturally proximate enough to become news, in international as well as national settings. Even a high degree of violence as part of serious conflicts may not always qualify as news if it does not involve the ‘right’ perpetrators or victims in the ‘right’ geographies of culture.” [98] Since 1945, there have been over 250 major wars and conflicts. Because most have taken place in the developing world with only a small number fighting across international boundaries, the media and the public choose to ignore their carnage. [99] The wars in East Timor, Liberia, Rwanda, Sudan, Somalia, Liberia, and Zaire were almost totally unseen by the West. [100] The artist Alfredo Jaar documented the lack of attention given to the Rwanda genocide in the piece Untitled (Newsweek). In the piece, Jaar assembles a chronology of Newsweek covers from April 1994, when the genocide began, through August 1994, when the magazine first dedicated its cover to the Rwanda massacre nearly 3 months after the killing had ended. The Newsweek covers show the importance given to the death of Kurt Cobain and the trial of O.J. Simpson over that of the 1 million slaughtered and another 4 million displaced. [101]

Images have become the war for public opinion. It is the images of war that create our understanding of its history and events. War has changed dramatically during that history. The gun was once considered cowardly because the shooter no longer had to look the victim in the eyes. [102] Just the same, the public no longer has to look into the eyes of war’s victims. War has become sanitized by the images that have come to represent it. When brutality and horror is removed from its images, for the audience it is removed from war itself. By censoring the images of war and controlling what the public sees, it lowers the barrier and resistance to war, as well as its criticism. Yet shocking images like the humiliation at Abu Ghraib are often not enough to create change. In the book A Century of Media, A Century of War, author and professor Robin Andersen comes to the conclusion,

The presentations of death, violence and the brutal images that visually characterize war have not always called forth its end . . . Looking at such pictures with detachment and justification robs the viewing public of its humanity. Another piece of compassion is lost with the acceptance of war’s brutality and the willingness to believe even questionable policies as justification for the deaths of civilians. Without the presence of a humanitarian perspective military conflict and war can always be prosecuted in the place of political diplomacy and policies. [103]

[1] The National Security Archive at GWU, Return of the Fallen, 28 Apr. 2005; 31 Aug. 2009.

[2] Cohen, Jeff and Mark Cook. Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. How Television Sold the Panama Invasion, Feb./Mar. 1990; 31 Aug. 2009.

[3] Gran, Brian. ‘The Dover Ban: wartime control over images of public and private deaths’. Unblinking: New Perspectives on Visual Privacy in the 21st Century, 2006, 5, at: http://www.law.berkeley.edu/bclt.htm

[4] Goya, Francisco. Disasters of War (Dover, 1967), back cover.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others (New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 44-45.

[7] Sontag, 2002, 46-47.

[8] Sontag, 2002, 50.

[9] Zelizer, Barbie. ‘When war is reduced to a photograph’, Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime, ed. Stuart Allen and Barbie Zelizer (Oxon: Routledge, 2004), 118-19.

[10] Sontag, 2002, 52.

[11] Landsberg, Mitchell. Fifty Years Later, Iwo Jima Photographer Fights His Own Battle, Associated Press, 24 Sep. 2009.

[12] Landsberg, 2009.

[13] ‘At 81, Japanese vet makes rare return to Iwo Jima’, AOL News Australia, 22 Sep. 2008; 24 Sep. 2009.

[14] Zelizer, 2004, 115.

[15] Katovsky, Bill and Timothy Carlson. Embedded: The Media at War in Iraq (Guilford: First Lyons Press, 2004), iv.

[16] Kahn, Jeffery. ‘Postmortem: Iraq war media coverage dazzled but it also obscured’, UC Berkeley News, 18 Mar. 2004; 20 Sep. 2009.

[17] Kahn, 2004.

[18] ‘Northern California teens scrutinize billion dollar military recruitment campaign aimed at youth’, ACLU of Northern California, 6 Aug. 2007; 6 Oct 2009.

[19] Hanna, John. CEO urges better press access to military ops, Associated Press, 6 Feb. 2009; 9 Sep. 2009.

[20] ‘Pentagon Spending Billions on PR to Sway World Opinion’, FOX News, 5 Feb. 2009; 9 Sep. 2009.

[21] Turse, Nick. The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2008), 142.

[22] Turse, 2008, 117-18, 157.

[23] Goodman, David. ‘A few good kids’, Mother Jones (Sep./Oct. 2009) 21-22.

[24] ‘Game Ratings & Descriptor Guide’, Entertainment Software Rating Board, 1 Oct. 2009.

[25] Clarren, Rebecca. ‘Virtually dead in Iraq’, Salon.com, 16 Sep. 2006; 13 Oct. 2009.

[26] Walker, James. ‘America’s army and the advergame double-standard’, Bing E Gamer, 24 Mar. 2009; 19 Oct. 2009.

[27] Brown, John. ‘The anti-propaganda tradition in the United States’, Public Diplomacy Alumni Association, 29 Jun. 2003; 16 Oct. 2009.

[28] Bernays, Edward. Propaganda (Brooklyn: Ig publishing, 2005), back cover, 12, 52.

[29] ‘The most famous poster’, American Treasures of the Library of Congress, 20 Sep. 2009.

[30] Sproule, J. Michael. Propaganda And Democracy: The American Experience Of Media And Mass Persuasion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 11.

[31] Woodrow Wilson. Episode 2: The Redemption of the World, dir. Carl Byker and Mitch Wilson, PBS, 2001.

[32] Johnson, Chalmers. The Sorrows of Empire (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004), 112.

[33] Turse, 2008, 111-112.

[34] Turse, 2008, 108-111.

[35] Johnson, 2004, 112.

[36] Turse, 2008, 103-111.

[37] Gran, 2006, 5.

[38] Hallin, Daniel. The Vietnam War, Museum of Broadcast Communication, 18 Sep. 2009.

[39] Sontag, 2002, 58.

[40] Democracy Now!, Pacifica Radio, New York, New York, 17 Mar. 2008.

[41] Griggers, Camilla. ‘War and politics of perception’, in Amitava Kumar (ed.), Poetics/Politics: Radical Aesthetics For The Classroom (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 220.

[42] Frascina, Francis. Art, Politics, And Dissent: Aspects Of The Art Left In Sixties America (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999), 171.

[43] Katovsky, 2004, viii.

[44] Naureckas, Jim. ‘Gulf war coverage: the worst censorship was at home’, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, 1991; 16 Sep. 2009.

[45] Naureckas, 1991.

[46] Naureckas, 1991.

[47] Humphreys, Donald. ‘War on television‘, The Museum of Broadcast Communications, 25 Sept. 2009.

[48] Sparks, Timothy. ‘The dawn of cruise missile diplomacy’, Naval Postgraduate School, Jun. 1997; 25 Sep. 2009.

[49] Kellner, Douglas. ‘The Persian Gulf War revisited’, in Stuart Allen and Barbie Zelizer (eds), Reporting War:Journalism in Wartime, (Oxon: Routledge, 2004), 144.

[50] Katovsky, 2004, vii.

[51] Kahn, 2004.

[52] Katovsky, 2004, xx.

[53] Katovsky, 2004, xi, 317-22.

[54] Janabi, Ahmed. ‘Focus: Interview with Sami Al-Hajj’, Al Jazeera English, 30 Jul. 2009; 28 Sep, 2009.

[55] Maguire, Kevin and Andy Lines. ‘Bush plot to bomb his Arab ally’, The Daily Mirror, 22 Nov. 2005; 28 Sep. 2009.

[56] ‘Al-Jazeera ‘hit by missile’’, BBC News, 8 Apr. 2003; 28 Sep. 2009 .

[57] Maguire, 2005.

[58] Press Emblem Campaign Report 2008, Press Emblem Campaign, 15 Dec. 2008, 6 Oct. 2009.

[59] Ernest Sagaga. The International Federation of Journalists 2008 Annual Report on Journalists and Media Staff Killed (Belgium: International Federation of Journalists, 2009), 2.

[60] ‘109 journalists died on assignment in 2008: report’, CBC News, 4 Feb. 2009; 6 Oct. 2009.

[61] Press Emblem Campaign Report 2008, 2008.

[62] Katovsky, 2004, viii.

[63] Reed, Charlie, et al., ‘Files prove Pentagon is profiling reporters’, Stars and Stripes, 27 Aug. 2009; 7 Oct. 2009.

[64] Baron, Kevin. ‘Military terminates Rendon contract’, Stars and Stripes, 31 Aug. 2009; 7 Oct. 2009.

[65] Zelizer, 2004, 131.

[66] ‘Marines help topple statue’; ‘Baghdadis loot city’, Fox News, 10 April 2003; 20 Sep. 2009.

[67] Zelizer, 2004, 117.

[68] ‘The death of a marine’, Associated Press, 4 Sep. 2009; Sep 29 2009.

[69] Shaer, Matthew. ‘AP photo of dying Marine draws fire from Pentagon’, Christian Science Monitor, 4 Sep. 2009; 29 Sep. 2009.

[70] Shaer, 2009.

[71] Lubold, Gordon. ‘The air force’s new poster boys: drone jocks’, Christian Science Monitor, 5 Jul. 2009; 2 Oct 2009.

[72] Singer, Peter W. Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (New York: Penguin Press, 2009), 32-33.

[73] Singer, 2009, 32-33.

[74] Lubold, 2009.

[75] Drew, Christopher. ‘Drones are weapons of choice in fighting Qaeda’, New York Times, 16 Mar. 2009; 2 Oct. 2009.

[76] Drew, 2009.

[77] Drew, 2009.

[78] Singer, 2009, 116.

[79] Lubold, 2009.

[80] Singer, 2009, 319.

[81] Singer, 2009, 316.

[82] Singer, 2009, 320.

[83] Steuter, Erin and Deborah Wills. At War with Metaphor: Media, Propaganda, and Racism in The War on Terror (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008), 89.

[84] Hersh, Seymour. ‘Torture at Abu Ghraib: American soldiers brutalized Iraqis. How far up does the responsibility go?’, New Yorker, 10 May 2004; 9 Sep 2009.

[85] Banbury, Jen. Rummy’s Scapegoat, Salon.com, 10 Nov. 2005; 9 Sep. 2009.

[86] Steuter, 2008, 89.

[87] Smith, Matt. ‘Soldiers put Iraq ‘war trophies‘ on eBay, CNN, 18 Mar. 2004; 6 Oct. 2009.

[88] Steuter, 2008, 87.

[89] Engelhardt, Tom. ‘Tomgram: David Swanson on war porn and Iraq’, TomDispath.com, 13 Jun. 2006; 6 Oct. 2009.

[90] Steuter, 2008, 88-89.

[91] Engelhardt, 2006.

[92] Sontag, Susan. ‘Regarding the torture of others’, New York Times, 23 May 2004; 4 Oct. 2009.

[93] Sontag, 2004.

[94] Zimbardo, Philip. ‘A few good apples’, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 2007; 21 Sep. 2009.

[95] Taguba, Antonio, Article 15-6: ‘Investigation of the 800th Military Police Brigade’ (Department of Defense United States of America, 2004), 5 Oct 2009.

[96] Taguba, 2004.

[97] Sontag, 2004.

[98] Sonwalkar, Prasun. ‘Out of sight, out of mind: The non-reporting of small wars and insurgencies’ in (eds), Stuart Allen and Barbie Zelizer, Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime, (Oxon: Routledge, 2004), 207.

[99] Sonwalkar, 2004, 210.

[100] Zelizer, 2004, 116.

[101] Alfredo Jaar, ‘Artist’s talk’, Tate Gallery London, United Kingdom, 13 Mar. 2008; 10 Oct 2009.

[102] Singer, 2009, 313.

[103] Andersen, Robin. A Century of Media, A Century of War (New York, Peter Lang Publishing, 2007), 102.

Chris Revelle is a conceptual artist who focuses on issues such as war and human and civil rights. He has a Masters of Fine Arts from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA and a Bachelors of Fine Arts from the Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA. Chris has worked with multiple United Nations organizations, as well as exhibited his works at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Santa Ana, CA; White Box, NYC; and the India Habitat Center, New Delhi, India. http://chrisrevelle.com