Stéphanie McKnight (Stéfy)

Since the start of the War on Terror, scholars, journalists, and artists have been actively engaging and contending with theories of privacy, preemption, data security, and contemporary surveillance.[1] Drawing from ongoing conversations relating surveillance to concepts of affect and visibility, I have begun building a body of work that questions surveillance as an invisible practice and uses art as a method of hypothetically shifting the ‘surveillant’ gaze through visual objects. My experimental photographs ALIEN, LEITRIM, and CODED, I AM, are a few of the works I’ve produced that bring into view surveillance spaces that are conventionally hidden and unseen. As part of my recent exhibition Hawk Eye View, these objects prove that art and cultural productions can contribute to larger academic and scholarly research of surveillance in North America post 9/11. These works act as a catalyst of understanding and questioning surveillance as a preemptive method of ensuring a survival state. This project considers production, cultural objects, and creation as a methodology that contributes to larger theoretical fields of study. Moreover, because of its visual nature, these works allow viewers to experience and interact with these cultural structures affectively and critically. What separates my practice from conventional surveillance studies interventions is my ability to produce visual works as methodology. Ultimately, my work aims to address how research creation and cultural objects contribute to current conversations about surveillance as a preemptive method of securing and policing Canada post 9/11; and how art and cultural objects function to critique and intervene with surveillance practices and technologies in a surveillance society.

As an artist and cultural producer, I explore the ways that visual images interpret political, cultural, and social divergences to facilitate audience involvement, interaction, and affect. Furthermore, my work considers how cultural productions translate knowledge in a way that encourages critical engagement, critique, and intervention. This paper will look at the research I have undertaken to retrieve this information and how I have rendered it—in two- or three-dimensional objects and a final exhibition. I am also interested in how surveillance technologies serve as a critical method of art production. This paper will examine the ways I’ve included technology such as QR codes and Google Earth images in my work to effectively critique surveillance technologies and metadata processes.

Hawk Eye View was exhibited in October 2015 at the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning in Kingston, Ontario, curated by Queen’s University doctoral student Michelle Smith. Consisting of experimental photographs, sculptural objects, and light installations, Hawk Eye View visually interrogates contemporary preemptive surveillance strategies integrated throughout North America. Focusing on Canada and the United States, Hawk Eye View considers how third-party data mining has compromised North Americans’ privacy. Predominantly, this body of work looks at Google Maps & Earth as a central mechanism for data mining and dataveillance because of its privacy policies and metadata retrieval processes.[2] Ultimately this project aims to bring attention to the specific ways Canadian citizens’ privacy has been negotiated through political and international agreements.

TERMS AND CONDITIONS MAY APPLY

I am drawn to how Google Maps & Earth allows users the opportunity to visually and virtually engage with sites, spaces, coordinates, and destinations. While it is obvious that Google Inc. retains cached information about coordinates, GPS tracking, and address searches, the implications of this on citizens’ and users’ personal information is hidden through its user-friendly interface. Web-based search engines such as google.ca are precarious in the way their privacy and terms of conditions constantly change without users being notified. I’ve made the striking discovery in my research that if I use google.maps.ca as a search engine, and then click on the Terms of Use or the Privacy section of the website, my web domain automatically shifted to google.com.[3] This signals that although Canadians rely on google.maps.ca as a primary tool for navigation and searches, because the program is created in the United States, Canadians must follow certain US codes and regulations. This claim has also been proven by a contemporary interactive web-based art installation by artist James Bridle—Citizen ex.[4]

This discovery led me to think about Google Earth & Maps as a direct link to how Canadians information is shared with other government parties, and the visual tools Google Inc. offers to its users. Artistic productions and creations allow artists and viewers to critique and engage with technologies by shifting their intended use. For example, artists have the opportunity to use a drone—historically created for surveillance, military and warfare use, and aerial viewing—as a method for creating art that critiques the drone’s original use.[5] By using the drone or technology as the medium for critique, the artist(s) and viewer(s) can visually contend with and understand the usage of the device. Similarly, I use Google Maps & Earth to critique how Google Inc. retrieves metadata that is shared with international governmental parties.

To do this, I found it particularly interesting and successful to use Google Earth images of NSA and CSIS surveillance sites.[6] NSA and CSIS surveillance processes function when they are hidden from view. There has been a lack of documentation and photographs of these sites available to journalists and citizens. Illustrating these sites through visual objects and productions gives viewers the opportunity to experience viewing sites that are normally doing the surveilling. Interestingly, to my knowledge, this is the first time that NSA sites and CSIS sites have been directly and visually represented alongside each other. All of the works in this exhibition are visually inspired and referenced from screen shots of Google Earth imagery of both NSA and CSIS sites found throughout North America. An example of this is Texas, which is a maquette composed of computer parts that re-visualize the NSA Texas intelligence site. The Google Earth images served as a reference, which inspired distorted, abstract reflections of the sites. The re-contextualization and visualization of these images signals some of the limitations found on Google Earth.

Figure 1. Stéfy, ALIEN, 2015. Experimental Photography, 24 x 36 inches. Kingston, ON. Photograph by Chris Miner.

Subsequently, the maquette became a point of reference for a photograph titled ALIEN (Figure 1) that further distorted the site and created a new mode of looking at NSA Texas. I use the term ‘re-visualize’ to emphasize the point that the images found on Google Earth & Maps are limited in the sense that Google Inc., in conjunction with other organizations, chooses what it visually represents on its site. However, it is important to recognize that although Google Maps poses certain visual limitations, the function of these images is to inform viewers and give them pictorial access to locations. By re-visualizing and contending with these images, we can complicate and further investigate their use. Moreover, before there were Google Earth & Map images, coordinates of NSA sites in the Snowden files, or photographs leaked on WikiLeaks, citizens had no direct way of visualizing and imagining these spaces. Information was being shared and sent to invisible clouds,[7] which we now understand to be intelligence sites. These works allow viewers to visualize these clouds and interrogate them. What citizens are historically conditioned to believe is invisible has become visible.

Figure 2. Stéfy, LEITRIM, 2015. Computer parts and light installation, 14 x 14 inches. Kingston, ON. Photograph by Chris Miner.

Works such as ALIEN both realistically and imaginatively illustrate a site, which encourages viewers to insert their own understandings and affective views of the site and photograph. Similarly, LEITRIM (Figure 2) is a maquette of a Canadian Forces Site located in Ottawa, Ontario. CFS Leitrim is the oldest Canadian operational signal intelligence collection station.

LEAKS

Additional, crucial tools used during my research and production were two web-based archives of leaked information: Cryptome.org,[8] the predecessor of WikiLeaks; and Lux Ex Umbra, a Canadian blog that monitors Canadian signals intelligence activities. Specifically, Cryptome’s Eyeball series looks at NSA and intelligence sites in both the United States and the United Kingdom, and provides users with the coordinates and addresses of these intelligence sites. Eyeball also offers screenshots and photographs of NSA sites, spy communities, and 9/11 documentation. The Eyeball series is intentionally visual, allowing viewers to experience sites through images. Lux Ex Umbra provides its users with a list of active and inactive intelligence sites in Canada. These databases are available online for use at any time. While this information has been consistently available to viewers, users often hesitate accessing these websites because of the possibility of being watched and monitored by NSA parties. When accessing these sites it is recommended that users mask their browser IP address to avoid being virtually followed and tracked. Despite this, Cryptome and Lux Ex Umbra are two very informative and enlightening web databases. Hawk Eye View uses technology to purposely give viewers access to this information in the comfort of a gallery space and without the fear of being tracked and monitored through these specific websites.

American artist Trevor Paglen, known for his photography and cinematography, interrogates American surveillance and security by photographing NSA sites in America. Paglen’s work Ft Meade[9] is a brilliant photograph that captures the largest data and information facility in the United States. Paglen’s work singularly brings attention to the lack of documentation of NSA sites in the United States. Paglen’s work asks, ‘What does surveillance look like’,[10] implying that citizens do not have the opportunity to view the sites that are normally doing the ‘surveilling’; or that surveillance is invisible and is only viewable by a higher power. More specifically his intention is ‘to expand the visual vocabulary we use to ‘see’ the U.S. intelligence community’. Nonetheless, he dismisses the circumstance that CSIS sites are also scarcely visually represented throughout history.

ALIEN and LEITRIM aim to fill this absence of CSIS and NSA documentation, by juxtaposing images of both sites. As outlined by David Lyon, NSA and CSIS institutions work closely and cohesively together to ensure a survival state[11]; thus it is necessary to view them as unified entities. Furthermore my work asks theoretical and arduous questions, such as: Why does surveillance appear invisible? Is surveillance invisible because our bodies and minds are normalized to surveillance processes? Or is data mining invisible because it is intentionally hidden behind interfaces?

My work contends with these questions by attempting to shift the surveillance gaze through using technology and by providing viewers with visual information. Ultimately surveillance is defined as an accumulation of knowledge and information to gain power of an individual or structure.[12] In a surveillance society, those who know more information are those who are dominant in the hierarchy. Websites such as Cryptome attempt to reclaim power by leaking and bringing attention to systems that are specifically hidden to remain in control. ALIEN and LEITRIM do this by bringing into view spaces that are fundamentally hidden to retain control. Additionally, Hawk Eye View incorporates technology to diversify the methods of looking at these sites.

TECHNOLOGY AS MEDIUM

Hawk Eye View incorporates contemporary technology such as QR codes to further investigate (1) the potential of technology in an art space; (2) surveillance technology as a method of art practice; and (3) how QR codes and cellular apps procure metadata. These codes allow viewers to access virtual representations of these sites without my intervention. The images shown through the codes are real aerial views that have not been artistically modified. They are images found on Google Maps that portray real time images of these coordinates. The images that appear when scanned are the images of reference I’ve used throughout my work. The QR codes act as a medium for viewer interaction, which allows them to experience how metadata functions and where this information is stored. When scanned using a smart phone or tablet, the QR code lead viewers to a Google Earth image of an NSA or CSIS site. The QR codes become a method of sharing normally hidden information. Additionally, by scanning this code, the user receives not only an image of the intelligence site in 360 and aerial view, they also obtain the coordinates, address, and visual and architectural knowledge of the space. If power is measured by information and knowledge, in this instance the viewer or user gains a sliver of control.

I would like to mention that in this moment my role is to provide viewers with the tools to do their own research and analysis of these sites. As a research creation performer, I am interested in how they will react and what they will do with this information. Will they choose to further investigate these claims and discrepancies? Or will they leave it, in plein air and ignore it?

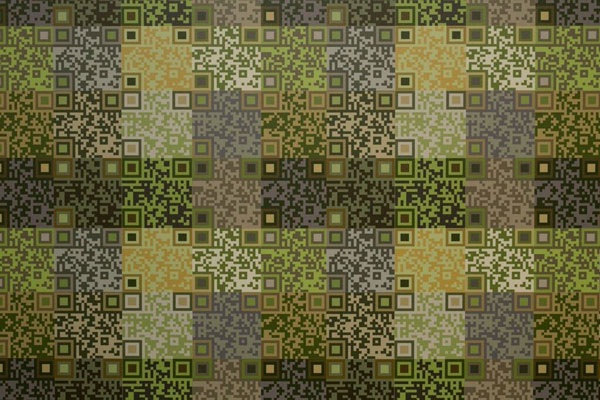

Figure 3. Stéfy, CADpat, 2015. Computer-generated pattern, mounted, 36 x 42 inches. Kingston, ON. Photograph by Chris Miner.

CADpat (Figure 3) receives its name from Canadian Pattern, a contemporary style of digital camouflage. The QR codes bears resemblance to the block-like pattern that is meant to digitally reduce the probability of being detected by night-vision technology.[13] Atypically, CADpat encourages technological intervention to reveal what has been instrumentally hidden. This juxtaposition of QR codes and Canadian Pattern signals, both metaphorically and literally, revealing cloaked spaces. At first glance, the QR codes camouflage and hide the sites that are normally doing the surveilling; however, the sites are revealed after the codes are scanned. This process reveals new ways of looking and engaging with the sites.

QR codes are consistently found throughout the series in the form of patterns, wallpapers, and tattoos. CODED is a wallpaper pattern, designed on Photoshop, filled with QR codes. Each of the codes found throughout the exhibition bring viewers to one of the ten Google Earth images of CSIS or NSA sites. Wallpaper is a domestic craft form. The QR codes work well with this notion of domesticity since most of the information of citizens that is being cached and stored is from the private sphere—from their computers and cellphones. Additionally, CODED, I AM (Figure 4) is a self-portrait that similarly contends with notions of domesticity, vulnerability, privacy, and personal information.

Figure 4. Stéfy, CODED, I AM, 2015. Experimental Photography, 24 x 36 inches. Kingston, ON. Photograph by Chris Miner.

Coded, I AM explores resistance and affect. As mentioned earlier in this paper, surveillance is most effective when there is a lack of affect. CODED, I AM aims to resist surveillance technologies by embodying and physically engaging with these processes. Resistance begins by acknowledging, contending, and recognizing the implications surveillance tactics have on citizens. In this self-portrait, I am in the process of challenging surveillance technologies by literally embedding them onto my body. My body becomes a system and engine of information and revelation. More concretely, CODED, I AM illustrates surveillance as a bodily process, one that cannot separate itself from technology and metadata retrieval processes.

5i

In 1998, section 215 & 702 of the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) ordered third-parties sites to turn over evidence and data if the US government saw it as relevant to an investigation. Section 215 was revisited and strengthened after the start of the War on Terror, in 2005.[14] Similarly in 2015, the Canadian Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness proposed implementing a new anti-terrorist bill of a similar nature: C-51.[15] By looking at Five Eyes—a negotiated partnership formed by Canada, the US, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand—it is evident that Canada and US surveillance plans are inextricably linked to one another. This project looks at the United States as a method of understanding and analyzing Canada’s surveillance society.

David Lyon writes, ‘the NSA act as the lead “eye” of the Five Eye’s partners’,[16] implying that the NSA is largely integrated into Canada’s policy and procedures. These assertions were also supported and brought to citizen’s attention by Edward Snowden in 2013. 5i, also known as Bug Eye (Figure 5), is a mosaic-like image that tessellates small images of NSA and CSIS sites to create a larger-scale image of Fort Meade. This manipulated image juxtaposes NSA sites and CSIS sites in a way that visually translates the partnerships and negotiations that happen between these sites and governments.

Figure 5. Stéfy, 5i, 2015. Experimental Photography, 24 x 36 inches. Kingston, ON. Photograph by Chris Miner.

Through Five Eyes, Canada, the U.S, UK, Australia and New Zealand cohesively work together to ensure an international survival state. 5i creates a visual way of critiquing, contending, and questioning these partnerships.

AFFECT, RESISTANCE AND AESTHETIC

My interest in surveillance art comes from my personal views on how surveillance and art are comparable practices. Contemporary surveillance is an artistic process in its use of visual mediums such as recordings, visual technologies, and video producing systems. Additionally, surveillance can be compared to contemporary arts through considering voyeurism, observation, looking, and affect. That art produces affect is a concept that has been extensively explored, contemplated, for example, by Simon O’Sullivan in his piece The Aesthetics of Affect. Drawing upon Deleuze’s writing on art, spectatorship, and affect, O’Sullivan writes that art is a bundle of affects or ‘bloc of sensations, waiting to be reactivated by a spectator or participant’.[17] Paradoxically, mass surveillance functions when there is an absence of affect. Affect encourages contemplation, resistance, and confrontation. Therefore only when a participant of mass surveillance is affected by these structures can they begin to negotiate and resist the surveillance mechanisms in place. Using art and research creation as a method of deconstructing surveillance systems is thus both practical and valuable.

Hawk Eye View was inspired by a lack of academic or artistic conversation that contends with contemporary dataveillance in Canada post 9/11 and the Snowden revelations. My intention is to bring attention to how international surveillance processes are affecting Canadians. I also see practicality in looking at international surveillance tactics and artists because, as mentioned and proven throughout this paper, Canada is heavily linked to other government parties. I would like to reiterate the importance of research creation and art when discussing these processes. Again, art gives us creative and innovative ways of experiencing cultural, political, and social matters through interactive and material modes.

While I recognize that Hawk Eye View is not the be all and end all, my objective is to provide viewers with the knowledge to intervene at their own pace. These works are translations of knowledge and fact, though it is the obligation of the viewer to decide how they will intervene and/or resist. It is also suitable to use the systems that are normally doing the surveillance as an artistic medium to better understand and contend with how these processes work and share personal information. Hawk Eye View does this by incorporating images from familiar web-based sites and downloadable apps that are known for procuring and storing user metadata. Interactively, viewers experience metadata retrieval through modern and visual ways.

Hawk Eye View was created as a method of facilitating knowledge and conversation. I anticipate that these conversations will change over time because surveillance society is rhizomatic and constantly adjusts to power institutions and structures. Fortunately, visual objects and cultural productions critically engage with ongoing societal vicissitudes and will continue to encourage viewer affect and negotiations. This conversation is only beginning.

Acknowledgements:

First I would like to acknowledge Dr. Jakub Zdebik and Zeina Hamod for including this paper in this issue of Drain. I would like to thank Michelle Smith for curating Hawk Eye View and the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning in Kingston Ontario for hosting the exhibition. I would like to extend my thanks to Dr. Susan Cahill from the University Calgary for her comments on this paper and for including me on her panel The Art of Surveillance at UAAC 2015. Further thanks go to Dr. David Murakami Wood and the Surveillance Studies Centre at Queen’s University for their ongoing support and knowledge, and Chris Miner for the documentation of my work.

[1] I use the term preemption as defined by Brian Massumi in his recent publication Ontopower. Massumi defines preemption as preparing for something that may emerge, based on an affective logic of potential. In this paper, contemporary surveillance is used as defined by David Lyon (Queen’s University). Contemporary surveillance includes new technological apparatus, including social media, CCTV, GPS, mobile devices and credit card transactions. Lyon David. ‘Contemporary Surveillance’, Interview published on YouTube, 28 July 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ov05EgnjMy0.

[2] Metadata is the time, location, email or number involved and date, attached to all types of technological activity, i.e.: cellphone texts, social media messages, searches, and transactions. Lyon, David. Surveillance after Snowden (Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, 2015), 66–75; Greenwald, Glenn. No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the US Surveillance State (New York, 2014); Snowden, Edward. Interview, (Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, 2015).

[3] .ca is a Canadian domain. I first came across this finding in August 2015. As of November 2015 this claim is remains valid.

[4] Citizen ex is accessed online at http://citizen-ex.com/. Citizen ex is a web-based app, which is downloaded on personal computers to track the users’ algorithmic citizenship. This installation tracks the users’ metadata and conveys to the user where their information is being sent to in the world.

[5] An example of an artist using a drone as a medium of art can be accessed at: http://smmcknight.com/2015/10/17/fuck/. In this video, I aim to critique global assumptions of surveillance in nature using a drone as a video recorder.

[6] NSA: National Security Agency, CSIS: Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

[7] I use the word ‘cloud’ throughout this paper to represent a Western idea of where our technological metadata and information is being sent. The cloud has been known to be ambiguous and not visible to its users.

[8] Cryptome: https://cryptome.org Lux Ex Umbra: http://luxexumbra.blogspot.ca.

[9] Trevor Paglen, Ft. Meade, 2014. Photograph.

[10] Paglen,Trevor. ‘What Does a Surveillance State Look Like’. The Intercept (2014), https://theintercept.com/2014/02/10/new-photos-of-nsa-and-others/ (26 November 2015).

[12] Lyon, David. ‘Chapter 2: Spreading Surveillance Sites’. Surveillance Studies: An Overview (Cambridge, UK: 2007), 24–25.

[13] Government of Canada. ‘ARCHIVED- Canadian Disruptive Pattern (CADPAT TM) Uniform’, National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces, 4 February 2002, http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/news/article.page?doc=canadian-disruptive-pattern-cadpat-tm-uniform/hnmx1bjg (29 November 2016).

[14] Clarke Richard A., Michael J. Morell, Geoffrey R. Stone, Cass R. Sustein, and Peter Swire. The NSA Report: Liberty and Security in a Changing World (Princeton, 2014).

[15] Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Bill C-51 First Reading (Ottawa, ON, 2015), http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=6932136&Col=1&File=4.

[17] O’Sullivan, Simon. ‘The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art beyond Representation’, Journal of Theoretical Humanities, 6:3, 2001, 125–135.

Stéphanie McKnight (Stéfy) is an artist scholar at Queen’s University. Her creative practice and research focus is policy, activism, governance and surveillance trends in Canada and North America. Within her research, she explores creative research as methodology, and the ways that events and objects produce knowledge and activate their audience. Recent exhibitions include “Park Life” at MalloryTown Landing and Thousand Islands for LandMarks 2017/Repères 2017, “Traces” at Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre, “ORGANIC SURVEILLANCE: Security & Myth in the Rural” at the Centre for Indigenous Research-Creation and “Hawk Eye View” at the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning. She has exhibited solo or group work at Modern Fuel Artist Run-Centre, the Isabel Bader Centre for Performing Arts, the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning, OCAD University, the WKP Kennedy Gallery and White Water Gallery. In 2015, her work Coded, I Am was shortlisted for the Queen’s University Research Photo Contest and Queen’s University 175 Photo Contest. In 2017, her work “hunting for prey” received an honorable mention for the inaugural Surveillance Society Network Arts Fund. Stéfy’s work has been featured in the January 2017 edition of LandEscape Art Review online contemporary art magazine in Europe. Stéfy is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in Cultural Studies at Queen’s University.