Natasha Chaykowski

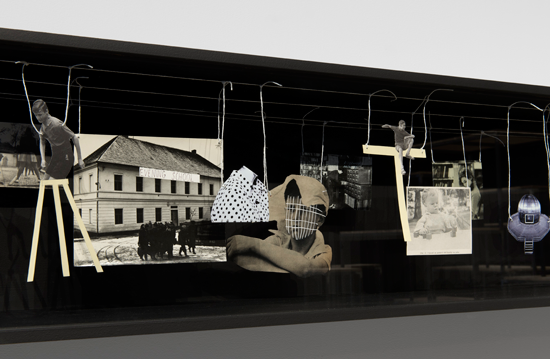

Eva Kot’átková, Untitled, 2014, Wood, collage on paper, glass. 14 feet. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

‘Ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars,’ wrote Walter Benjamin. Benjamin’s whimsical comparison suggests that objects—the solid stuff of the universe—are immutable[1], while ideas exist malleably in the ether, interpreting and making sense of the otherwise chaotic night sky. This logic that sees objects as stable fixtures and ideas as the immaterial stuff between them is troubled in Czech artist Eva Kot’átková‘s recent solo exhibition at Scrap Metal Gallery in Toronto.

Kot’átková‘s relationship to objects and ideas is perhaps best described as irresolute; her use of dated instructional manuals, elementary grammar guides and bits of re-arranged found visual culture in this exhibition suggests that ideas, while making temporary connections among and around objects, also exist within these objects. Such ideas, and their accumulations that create overarching ideologies, live on the weathered pages of books bound by crumbling glue and on the banal surfaces that create schoolrooms, hospitals and many other institutional spaces. In turn, the ways in which these ideologically laden objects exert a sort of control over and indoctrination of those who encounter them—by choice or necessity—is pointed to in Kot’átková‘s surrealist collages, uncanny metal figures and phantasmagoric installations.

Eva Kot’átková, Untitled (from the series Parallel Biography)(installation view), 2011, Mixed media (wheelchair with welded metal cages (2 feet and 1 head), book holders and book), Dimensions variable, collection Dr. Paul Marks, Toronto, Canada. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

In Untitled from the series Parallel Biography (2011), a wheelchair-turned-prison sits vacant and menacing with rough metal cages where ones head and legs would be. This, with its sturdy wooden structure and rusted wheels, recalls the pathos of how a contemporary imagination might (maybe inaccurately) envision a nineteenth-century asylum—it conjures dramatic images of wrought iron bed frames, leather straps to bind limbs and cruel nurses walking down seemingly endless corridors, the sounds of their steps echoing among the rows of rooms. But in Kot’átková’s work there is perhaps some reprieve; attached to the device is a contraption that suspends books in front of the otherwise confined reader. Intellectual escape! This luxury, however, is deceiving; what might initially seem a relief is indeed only further repression, as books, for Kot’átková, are as restrictive as metal cages. In this work, ideological incarceration through reading is equated with physical confinement and each respectively polices the behaviours of those imprisoned by them.

Another of her sculptural works, House Arrest No. 4 (2010), is a colorful knit sweater that bears the weight of a similar metal contraption, this time a sort of corset, that forces its wearer to confront books suspended from its protruding arms. How to be Healthy, Erstes Rechenbuch (My First Arithmetic Book) and other books are propped up by the cool metal arms of the device. The artist’s fascination with books is often attributed to idiosyncratic experience and biographical detail; Kot’átková was a young pupil in Czechoslovakia during the transition from Communist rule to parliamentary republic—a transition that saw textbooks and instructional materials, the stuff of supposed objectivity, change abruptly. Truth here is revealed as fickle, and objectivity is proved false. But can the realization of ideological inconsistency undermine the power of the ideas nestled neatly in the pages of books?

Eva Kot’átková, House Arrest No. 4, 2010, Metal construction, sweater, books. 66 x 13.7 x 34.6 inches, collection Dr. Paul Marks, Toronto, Canada. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

Kot’átková reckons with this question in exercising a sort of controlled violence against these materials that parade under the guise of objectivity, seeking to ensnare unwitting subjects in particular ideological traps. A mounted vitrine spanning the length of an entire gallery wall uses a visual vernacular much in the vein of avant-garde photomontage. While such artists were compelled by the need for a new language to bypass the limits of photographic convention as a means to articulate a foil to inter-war gender politics and to reckon with the unprecedented devastation of the First World War, Kot’átková strives to point to the influence of images and objects on human behavior. The painstakingly crafted cutouts, found photos and other materials are suspended from bits of twine inexactly tied in little knots, evoking elementary school crafts. And unlike the typically two-dimensional photomontage, this work is a diorama, reinforcing the association with childhood bricolage. But these crafts have gone awry: the black and white images and photographs are intervened upon with iridescent white ink. Cages around children’s bodies and masks upon their faces, imaginary ropes anchoring them to the ground and arrows protruding from otherwise innocent eyes are the kind of violence that Kot’átková inflicts upon her faded and de-contextualized image-matter. In dislodging images from their homes—the books, magazines and albums that they once lived in—and intervening upon their surfaces, Kot’átková reverses and makes apparent the otherwise veiled power of objects to collectively enforce the ideologies infused into institutions like education and the nuclear family. In Kot’átková’s dystopic nostalgia, these institutions are stripped bare and the bars that make their cages are exposed.

Eva Kot’átková, Untitled (detail), 2014, Wood, string, collage, glass. 32.5 feet. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

Eva Kot’átková, Untitled, 2014, Wood, string, collage, glass. 32.5 feet. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

What is perhaps most compelling about Kot’átková’s intricately structured critique of institutions is that it relies implicitly and paradoxically on the institutions of art (galleries, curators, collectors, biennales, this publication, etc.), all of which exert their own kinds of power and confinement. But, institutional critique is a well-worn narrative in the art world, and art, after all and if nothing else, is an institution with a remarkable stamina for critical introspection. Better still, perhaps Kot’átková’s cages and weathered books, her unease with the regiment of learning, could only exist in a gallery; its traction is derived from its artful use of other institutions—its admittance that there is no way to exist outside of their confines. This realization, that confinement to a figurative cage is unavoidable, is only eased by the fact that through the bars, the night sky can still be seen.

Eva Kot’átková, Untitled (detail), 2014, Collage, wood, steel, string, pins, antique books, children’s shirt. 74 x 70 x 3.5 inches. Courtesy the artist, Art en Valise, Scrap Metal Gallery and Meyer Riegger.

[1] Except for the odd white dwarf that will perish, slowly fizzling out of existence, every several billion years or so.

Natasha Chaykowski is a Montreal-based writer and curator. She has organized numerous exhibitions, discursive programs and arts-based events. Chaykowski held a curatorial assistant position at Art Gallery of Ontario, co-curated the annual Emerging Artist Exhibition at InterAccess in Toronto with Nancy Webb and is the co-recipient of the 2014 Middlebrook Prize for Young Canadian Curators. She was Editorial Assistant for the Journal of Curatorial Studies and the Editorial Resident at Canadian Art Magazine in 2014. Her writing has been published in Carbon Paper, the Art Gallery of York University, esse: arts + opinions, Canadian Art, Gallery 44, and the Journal of Curatorial Studies.