Yoanna (Yoli) Terziyska

Why are we fascinated by ruins? They recall the glory of dead civilizations and the certain end of our own. They stand as monuments to historic disasters, but also provoke dreams about futures born from destruction and decay. Ruins are bleak but alluring reminders of our vulnerable place in time and space.

-Brian Dillon[1]

Ruin Lust was an exhibition that recently took place at London’s Tate Britain; it presented its viewers with a narrative of artists’ fascination with ruins. The participating artists in the exhibit were predominantly British, from J.M.W. Turner and John Constable to contemporary figures such as members of the Young British Artists, Rachel Whiteread and music journalist Jon Savage. Curators Brian Dillon, Emma Chambers and Amy Concannon divided the show into eight sections. The audience was guided through the museum’s spaces, where the exhibition’s intent is clearly stated: to create an historical overview of the ways in which ‘the ruin’ is understood and perceived as an object and carrier of symbols. This history begins in the eighteenth century, when European culture was gripped with an intense fascination for this subject, as seen through the first series of works displayed at the exhibition’s entrance.

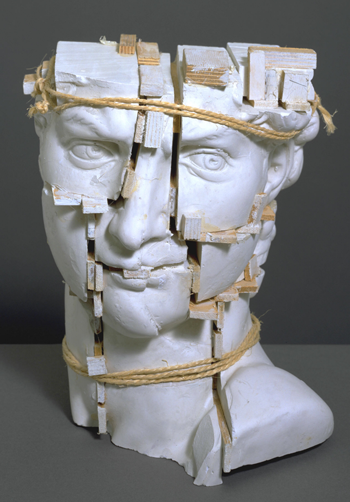

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, Michelangelo’s ‘David’, 1987, Ruin Lust: 4 March – 18 May 2014. Image courtesy of Tate Britain. Tate © DACS 2013.

Although the first group of works seen when entering the space date from the seventeenth century—works by artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Constable—the show does not follow a linear chronological pattern that maps out an evolving relationship with ruination. Rather, it groups works from different epochs that share a symbolic thematic, bringing in a wide range of pre-modern, modern and contemporary artists next to each other in their exploration of this seductive and curious object and idea. The artworks’ mediums vary as much as their specific subject matter: painting, photography, drawing, new media, multimedia art and installation were all present.

There were a few key themes concerning ‘the ruin’ present here; the German term ruinenlust (ruin lust) was resurrected by Rose Macaulay in her 1953 study, Pleasure of Ruins[2], temporally situating the phenomenon in the Modern period. She argues that ruinenlust is associated with the pleasure found in ruins—a pleasure that may derive from the beauty found in desolation and decay, from an imagining of a past (and thus a future), from destruction and the hope for rebirth or from an understanding of the passage of time and the inevitability of death.

John Piper, St Mary le Port, Bristol, 1940, Ruin Lust: 4 March – 18 May 2014. Image courtesy of Tate Britain.

Ruin Lust proposed that one of the sources of inspiration for artists’ treatment of ruins is derived from Classical ruins—those of ancient Greece and Rome. These ruins compelled Romantic painters such as Turner and Peter van Lerberghe to produce works that demonstrated an enthusiasm for the picturesque. In their works, ‘the ruin’ is depicted as an authentic object set in a natural landscape. These enchanting images show the decay of spoils and the triumph of nature.[3] For such Romantic artists, ‘the ruin’ evoked the past and stood as a relic of a great culture; they painted nobility wandering through imaginary mystical gardens, marveling at the beautiful symbols of a fading Classical history.

Beauty and wonderment, however, were not the only thematic ties to ruin in the exhibition. Some artists also depicted ‘the ruin’ as a symbol of commemoration, or perhaps mourning, of near and distant pasts. Tacita Dean’s Kodak (2006) is a film installation that studies the medium used for the production of her work. Kodak is a 44-minute video made using the 16mm Kodak film stock that is, today, an obsolete product. Through the use of a dying medium, Dean expresses the process of technological revolution and change that transforms objects that once symbolized social, cultural and economic progress, into relics. These objects, once replaced by their upgraded successors, are left behind as ruins of technological development that can be consumed fetishistically as ‘retro’ items—or as ruins of a more recent, romanticized past.

Jane and Louise Wilson, Azeville, 2006, Ruin Lust: 4 March – 18 May 2014. Image courtesy of Tate Britain. Tate © Jane and Louise Wilson.

As well as symbolizing progress, ‘the ruin’ was also shown as a symbol of destruction and desolation in the exhibition. The devastating nature the First and Second World Wars removed romantic associations with ‘the ruin.’ Instead, for postwar artists, ruination signified horrors of a recent history, and as such warranted a different aesthetic approach. This led artists to visually explore new avenues for understanding ‘the ruin’—Keith Arnatt and his photographic series from 1982-4, A.O.N.B. (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty,) being an example of this. These photographs show abandoned roadside locations such as homes, restaurants, outposts and street signs, which convey the lack of presence of humanity—a presence that was there not long ago. What is left of the people that occupied and gave life to these environments are ruins that now show desolation and abandonment. Whiteread and Savage—both native Londoners—similarly explore ruins through this lens. While Arnatt’s photographs serve to document decay, Whiteread and Savage’s dreary images are imbued with the promise of rebirth and a reimagining of ruined environments.

In Demolished-B: Clapton Park Estate (1996), Whiteread shows the tearing down of the Hackney tower blocks. These buildings represent the ruins of a residential community exiled by the decline of industry in London’s Hackney area. In Savage’s series Uninhabited London (1977-2008), the photographer captures different locations in a state of abandonment and fragmentation, scattered throughout London. These areas, however, are understood by Savage as places of great potential for restructuring. ‘The ruin,’ for Whiteread and Savage, is an indicator of regrowth, a symbol of change, and an opportunity for the birth of new histories and meanings.

But, why Ruin Lust?

Discussing the show’s title is as important as discussing its contents in that it holds a significance that has been overlooked in the discussion the exhibition’s aim—mapping out the alternative ways of understanding ‘the ruin’ as a subject and its array of symbolic functions.

Patrick Caulfield, Ruins, 1964, Ruin Lust: 4 March – 18 May 2014. Image courtesy of Tate Britain. Tate © DACS 2013.

The title is undeniably very alluring, given the direct and sensuous nature of the word ‘lust.’ It is comprised of two nouns, ‘ruin’ and ‘lust,’ which share a core commonality: the complex relationship between objecthood and representation. This very relationship informs the particular selection of artworks in the exhibition—artworks that present the ruin’s symbolic power.

Ruin: ‘The ruin’ is a physical object; it is built of matter. This matter bears the scars of time, thus functioning as a marker of its passage and a direct symbol of life and death. ‘The ruin’ is a part of history, and stands as a referent to a specific past. It is a physical fragment that belonged to, and now is severed from, a whole that no longer exists. Because the existence of a fragment of a ruin presupposes the existence of another object, ruins begin to lose their innate qualities as independent physical matter, and instead become symbolic carriers of history’s traces. This places them in the complex position between objecthood and representation.

Lust: The term is saturated with romance and a dismissal of time. Directly associated with desire, lust is an aesthetic experience of yearning for something that is not present for consumption. Its very existence demands the absence, or inability, to fully possess or grasp the object (or subject) of desire. Similar to the relationship felt with lust, ‘the ruin’ presents us with a fascination with a non-present entity that exists as a symbolic trace in our consciousness. Thus, both in lust and ruination, we participate in a futile exercise for grasping the authentic, absent whole.

[1] Dillon, Brian. Ruin Lust, exhibition catalogue, (London: Tate Publishing, 2014), back cover.

[2] Macaulay, Rose. Pleasure of Ruins (London: Nabu Press, 2011).

[3] Dillon, 2014, 10.

Yoanna (Yoli) Terziyska lives and writes in Toronto. She is the co-founder and development officer for the digital art criticism publication, KAPSULA Magazine. She recently began to work for ArtSlant as its Toronto staff writer—starting September, you can find more of her writing on ArtSlant’s website. Terziyska holds an MA in contemporary art history and an arts and business degree from Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London, UK. Feel free to contact her at yoli.terziyska@gmail.com.