Amy Kazymerchyk

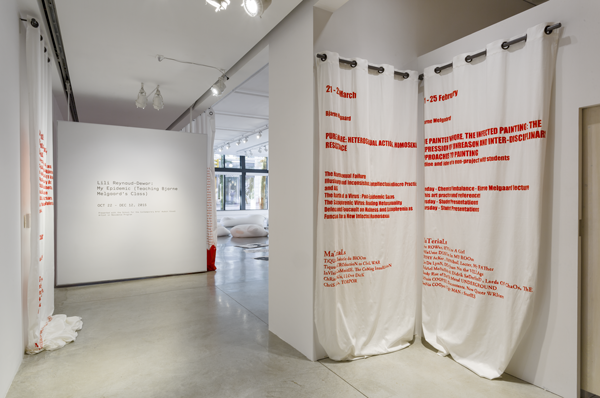

All images: Lili Reynaud-Dewar, My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class). SFU SCA Seminar with Alexandra Best, Kayla Elderton, Jorma Kujala, Siena Locher-Lo, Chris Mark, Emily Marston, Weifeng Tang, Cory Woodcock, Sitong Wu, Viki Wu, Nicholas Yu. Installation view, Audain Gallery, 2015. Photos by Blaine Campbell.

In her essay Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag argues that the production of symbolic values around illnesses such as cancer compromise an ill person’s welfare.[1] She focuses on the production of metaphors, a figure of speech which makes a comparison between two things that are unrelated to evoke the quality, feeling, or value of one in the other. Western psychology has contrived spiritual and psychological metaphors about an ill person’s constitution; religious institutions have articulated moral and punitive metaphors about an ill person’s actions; and governments have endorsed militaristic metaphors for an illness’s transmission.[2] These metaphors are dangerous because they distort public impression and response to an illness by confusing the specificity of its condition. Ten years later, Sontag wrote an addendum essay titled AIDS and Its Metaphors that highlights the metaphors that have been attributed to the bodies, subjectivities, and actions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and their broad effects on kinship, citizenship, and economics.[3] Sontag refutes these metaphors’ value, citing the ideological and scientific paradigm shifts that have inspired then disputed them, as evidence of their fallacy. She supports the position that an illness is just a biological mutation that modulates biological signals, and therefore thinking about them figuratively only impedes medical attention.[4]

Holding Sontag’s thesis in mind, what does it mean for artists to take up epidemics, and AIDS in particular, in the context of contemporary art, which is premised on symbolic production? And what does it mean for this symbolic production to be staged in a white cube, which is not unlike the institutions such as psychiatric wards, courthouses, and lecture halls where the lives of people living with AIDS are negotiated, often based on unstable metaphors?

Even if artists refuse the unstable metaphors attributed to persons living with AIDS in their work, are there ways in which these metaphors and their permutations have been transmitted through juridical, educational, religious, medical, and financial institutions, that are worth reflecting on? Could the operations of these metaphors be exposed by taking up epidemic—an illness that spreads rapidly by infection to a large number of people in a shared geography at a given time—as a metaphor for the complex social conditions that produced them? Could viral—the spread of an infectious virus—be a meaningful metaphor for the production of identity, collective action, and artistic production in resistance to them?

In her serial project My Epidemic, French artist Lili Reynaud-Dewar considers these questions by teasing out the material and figurative language of AIDS and its impact on bodies and culture. She applies the clinical language of epidemiology—the study of contagion, transmission, and effects of disease—to artistic, intellectual, and social life, to demonstrate how ideologies spread virally, far beyond ill bodies, through all social institutions. The possessive My in the project’s title implicates Reynaud-Dewar’s own life, art, and politics in AIDS, along with all the ideological, aesthetic, and political epidemics she has lived through, been formed by, and contributed to.[5] My also suggests that every participant in a society both possesses an epidemic via ideological infection and propels its transmission. It suspends the negotiation of singular and collective identity without prematurely erecting the façade of our.

My Epidemic emerged in 2015 as a series of artworks, exhibitions, seminars, and a publication that highlight the intimate and social lives and politics of artists, writers, and activists. The series evolved from her earlier exhibitions Vivre Avec Ça?! / Live Through That?! (2014) and I Am Intact And I Don’t Care (2013), which took up the life and work of Guillaume Dustan, a French writer and a controversial figure within Paris’s queer milieu whose books include Dans ma chambre/In my room (1996) and Nicolas Pages (1999).[6] In my room is an intimate and explicit account of his sexual and emotional relationships set within his apartment, the apartments of his lovers, and the shared nest of gay nightclubs and social sex rooms. In these installations the formal language of the room occupies the public gallery with belongings from the private realm, such as curtains, small beds, and men’s pajamas. In these installations the spilled ink of Dustan’s personal life soaks the blank pages of the bed sheets and a voice reading from his books emanates from speakers in the bed frames. These iterations reflect on the tension between the intimacy and politics of the singular body and the social body; between the maker’s body, the body of work, and its reader.

Reynaud-Dewar’s reading of Dustan’s life and work expanded to address the public tension between himself and French writer, journalist, and Act-Up activist Didier Lestrade around conflicting personal and collective politics regarding social sex culture and barebacking. Dustan challenged Act-Up France’s regulation of queer sexual culture, and supported radical queer autonomy against state management, communal surveillance, and moral control of queer bodies and health. Reynaud-Dewar scripted a libretto about their turmoil titled My Epidemic (small modest bad blood opera) and presented it in All the World’s Futures at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015.[7] Parallel to her installation she hosted a seminar with her students from the Haute École d’art et design in Geneva, in which the group read aloud from Leo Bersani’s Sociability and Cruising (2002), Douglas Crimp’s De-Moralizing Representation of AIDS (1994), Tim Dean’s Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking (2009), Samuel R. Delany’s Three, Two, One, Contact: Times Square Red (1999), Guillaume Dustan’s Dans ma chambre/In my room (1996/98), and Scott O’Hara’s Rarely Pure and Never Simple (1999).

While producing (small modest bad blood opera), Reynaud-Dewar encountered a similar artwork produced for the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011. A Norwegian artist had conceived of a project that took up the AIDS epidemic as a way of entering a discussion on the production of identity, collective action, and artistic production that was organized as a series of classes culminating in a collaboratively produced exhibition. The artist was Bjarne Melgaard and his seminar, titled Beyond Death: Viral Discontents and Contemporary Notions about AIDS, featured books and videos on a range of topics including abortion rights, gay marriage, police brutality, and depression. In the weeks leading up to the Biennale, students at the Università IUAV di Venezia read texts and produced their own writing and artwork that became part of Melgaard’s installation Baton Sinister, commissioned by the Office for Contemporary Art, Norway, as part of their national representation.[8] A catalogue of his project, which included the seminar’s syllabus, was produced by the Hauger Art Museum.[9]

For her iteration of the My Epidemic series at SFU Galleries’ Audain Gallery in 2015, titled My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class), Reynaud-Dewar took up Melgaard’s discussion on the production of identity, collective action, and artistic production, via the autobiography, prose, and critical theory of writers living with, responding to, and circulating around AIDS.[10] She facilitated this discussion through the transmission of his seminar as well as his persona. For the exhibition, which was presented in tandem with her teaching post as the Audain Visual Artist in Residence in Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts (SCA), Reynaud-Dewar performed Melgaard and interpreted his syllabus as she encountered it in the Baton Sinister catalogue. She edited his seminar into a course of eight, six-hour sessions that were held in the gallery for undergraduate and graduate SCA students.[11] During the sessions students read aloud from the texts, presented on their own practices, and produced their own images in response to the readings. (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class) encompassed Reynaud-Dewar’s installation, the performance of the seminar which took place during gallery hours, a guest lecture and performance by Swiss artist Ramaya Tegegne, a video by BOOK TV, and the images that the students produced and contributed to the installation.[12]

To set the material and conceptual stage for the seminar Reynaud-Dewar pulled quotes from the books in Melgaard’s syllabus and painted them on white curtains that lined the institutional walls, creating an anteroom within the gallery. Quotes were selected from Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (2004), Kathy Acker’s The Birth of the Poet (1981), and Mumia Abu-Jamal’s Panther Daze Remembered (1989), among others.[13] Reynaud-Dewar’s selection and composition of quotes were less faithful to why Melgaard selected the texts and how he taught them, and more invested in how his ideas were transmitted through contemporary art–in this case an exhibition catalogue–for her to receive, interpret, and expand upon. Her selection expressed her interpretation of the relations and contingencies between The Black Panthers and ACT-UP, the pro-choice movement and bareback subculture, and queer marriage and family advocates and skeptics. They also exposed the tensions between the desires and needs of singular and collective bodies, private and public space, and personal and social support. The material presentation of the quotes made visible the transmission of political and cultural values that have infected every aspect of our lives, from women’s reproductive rights to racialized violence. The curtains enveloped the gallery in a suspended timeline of the entwined politics of sexuality, procreation, sovereignty, and death.

The quotations infected each other in the gallery, and in turn infected the students in the seminar and visitors who read and spoke them. For many of the students who were born after 1990, Reynaud-Dewar’s seminar was their first opportunity to talk about AIDS personally and socially. AIDS may have only been a metaphor in their lives until they encountered historical material to ground the epidemic within the exhibition. The white cushions that Reynaud-Dewar designed to be the armatures for the seminar were impressed with the bodies of students and visitors who committed time to reading the curtains that enveloped the room and the seminar books scattered around them. The books’ covers were reimagined by students who translated, edited, and composed their own image works, which were printed out as posters that accumulated across the gallery floor. Each student and visitor who read, reflected, and interpreted the installation contributed their own My to the exhibition.

The alignment of Melgaard’s and Reynaud-Dewar’s projects, which sees production methodologies, formal strategies, and installation vocabularies echoed consciously and unconsciously across time and space, is an example of virality within contemporary art. Artists’ identities and their practices are infected by influences they encounter personally or through text, image, audio, and video documents. These synchronicities are often considered plagiarism, but I think they are productive exchanges in which contagious ideas spread through artists’ quoting, mimicking, and translating each other. The transmission of ideas is a form of epidemic and the virality of discourses influences the production of identity, collective action, and artistic production. This of course includes the refusal to identify, participate collectively, or create productively.

In (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class), Reynaud-Dewar performed Bjarne Melgaard. She wore a finely tailored suit in his approximate size (much too big for her), identical VANS sneakers, a haircut approximating his G.I. short crop, and a ball cap from one of his installations. She studied how to perform Melgaard by looking at images and videos of how he performs himself, similar to how people watch videotaped lectures and adopt speakers’ ideas into their own thinking and producing. Reynaud-Dewar was not being Bjarne Melgaard, she was absorbing how his artistic and pedagogical practice has infected her own. Two videos installed on monitors in the exhibition picture her nude body painted the same hue of red as the quotes on the curtains, dancing, reading, and thinking in the empty gallery and in the installation in progress. They portray how she performs thinking physically, conscious of how her body is being formed by the gallery and the university, and by ideological, aesthetic and political epidemics they proliferate.

For students in the seminar, working in the gallery also offered them the opportunity to think physically about how their bodies are formed by the contemporary art and the post-secondary education; to feel how these institutions, their discourses, and their ideological epidemics infect their own artistic practices; and to contend with how the discourses and policies produced within the white walls of institutions will determine their public and personal lives.

On the last day of the seminar myself, Reynaud-Dewar and the students hosted a public conversation about the project in the gallery. SFU faculty, SFU Galleries staff, members of the contemporary art community, artists, academics, activists, and peers participated in what extended into a three-hour discussion that took seriously the project’s provocation to address the tensions between the intimacy and politics of the singular body and the social body, and between the maker’s body, the body of work, and its reader.

In particular, questions regarding the artist and curator’s consideration of, and engagement with the current social and political conditions entwined with AIDS in the neighborhood that the gallery is situated in were raised.[14] These encompass, but are not limited to, conditions of addictions, harm-reduction, gentrification, the stigmatization of mental health illnesses, and the criminalization of street-based sex work. These questions provoked a dialogue regarding the responsibilities that artists, curators, educators, and institutions have to being aware of and responsive to, the conditions of an art work’s presentation and reception. Some expressed the opinion that Reynaud-Dewar and myself did have a responsibility to engage with the site-specificity of her artwork’s presentation and some expressed counter opinions that My Epidemic is precisely an encounter with difference via cultural production, and that the felt distance and intimacy of temporal, spatial, and subjective difference, through encounters with books and art are what motivates the project.[15]

Questions regarding how artistic, cultural, and intellectual work more broadly attends to historical, social and political conditions were also raised. In order to seriously consider what the relations and contingencies are between ideological epidemics such as reproductive rights, systemic racism and pathologized sexuality, whose perspectives on the conditions and consequences of them are speaking and being spoken to? Whose My’s are amplified in volume and repetition, and whose are not even being uttered? Whose books are on our shelves, in our syllabi, and in our artworks? Whose artistic practices are we absorbing? And whose artworks are in our galleries?[16]

It has been seven months since (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class) was de-installed and this conversation is still present with me. At times I’ve questioned whether parts of the conversation were unconsciously grounded on presumptions fueled by a legacy of metaphors about who has AIDS, whose lives are affected by AIDS, and the lifestyle conditions in which AIDS is transmitted. Was an assumption being made that the demographic who were enrolled in Reynaud-Dewar’s seminar–people born after 1990 who attend university and are interested in art––do not live with AIDS? One of the intentions of the project I appreciated most was that it addressed people who are unassuming transmitters of an ideological epidemic. This tactic revealed complex and nuanced ways that people’s lives are entangled with AIDS and the burden of metaphors, and expanded the conversation on what intimate and public signifiers define one’s personal identity and unify people socially and artistically.

On 17 December 2015, Just five days after (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s) Class closed, the Tacoma Action Collective staged a die-in within the exhibition Art AIDS America at the Tacoma Art Museum to protest the under-representation of black artists in the exhibition—five of one hundred seven.[17] The Tacoma Action Collective made three demands, ‘ “more Black staff at all levels of leadership” at the museum; “Undoing Institutional Racism” retraining for staff and board; and greater black representation within the Art AIDS America exhibition for when it tours nationally in 2016.’[18] I had visited the exhibition the week prior, after one of its curators, Jonathan David Katz, spoke about it at Simon Fraser University. ‘How does one attend to history?’ echoed in my mind as I walked through the TAM exhibition, and later when I read journalism on the die-in and the conversation between the Tacoma Action Collective and curators Katz and Rock Hushka that it provoked.

As a participant of a parallel social institution, in this case a gallery, where the lives of people living with AIDS are being negotiated, I continue to think about how to resist unstable metaphors. If epidemic and viral are to be taken up as metaphors for the complex social conditions that produced them, how does one make decisions about what ideologies to spread and to refuse? If they are taken up as metaphors for artistic production, whose artworks and ideas does one choose to absorb and proliferate? Returning to Sontag’s apprehension, how does one choose metaphors that don’t further distort public impression and response to an illness by confusing the specificity of its condition and compromising the medical and social welfare of bodies that are ill?

[1] Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978). She also reflects on the way in which epidemics such as the plague, tuberculosis and syphilis were treated.

[2] Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Doubleday,1989), 94–100, 113.

[3] Ibid., 103–104,109–115. From this point forward I will address HIV/AIDS as AIDS.

[5] The first chapter of her book My Epidemic (texts about my work and the work of other artists) published by Paraguay Press in 2015, traces her own encounters with AIDS. The subsequent texts exemplify conceptual and material virality within art, literary and activist practices.

[6] Live Through That?! at the Logan Centre for the Arts, Chicago (2014); Emanuel Layr, Vienna (2014); Outpost, Norwich, UK (2014); Index, Stockholm (2014); New Museum, NY (2014). Vivre Avec Ça?! at Kamel Mennour, Paris (2014). I Am Intact And I Don’t Care at 21 er Raume Belvedere, Vienna (2013); CLEARING, Brooklyn, NY (2013); Lyon Biennial (2013); Frieze Projects, London (2013).

[7] All the World’s Futures. Venice: Venice Biennale. Curated by Okwui Enwenzor. 9 May – 22 November, 2015.

[8] Baton Sinister. Venice: Palazzo Contarini Corfù. Coordinated by Office for Contemporary Art Norway. 31 March – 16 May, 2011.

[9] Melgaard, Bjarne. Baton Sinister (Tønsberg, Norway: Haugar Art Museum, 2012).

[10] My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class). Curated by Amy Kazymerchyk. Vancouver: SFU Galleries, Audain Gallery, Simon Fraser University. 22 October– 12 December, 2015. I would like to acknowledge Melanie O’Brian, Director of SFU Galleries; Judy Radul, Coordinator of the Audain Visual Artist in Residence program; and Denise Ryner, SFU Galleries Curatorial Intern, for their contribution to the development and presentation of the exhibition.

[11] Participating SCA students were Alexandra Best, Patrick Blenkarn, Kayla Elderton, Jorma Kujala, Siena Locher-Lo, Chris Mark, Emily Marston, Neo Tang, Cory Woodcock, Sitong Wu, Viki Wu and Nico Yu.

[12] Ramaya Tegegne performed You don’t always have to be you to be yourself: Version#17: Annie Sprinkle at MODEL Projects on 23 October, 2015. BOOK TV is a web-series initiated by Géraldine Beck that features artists, theoreticians, specialists, aficionados or collectors discussing the books they are reading. Beck, Géraldine. “#06: Lili Renaud-Dewar: My Epidemic,” BOOK TV, accessed 28 June, 2015, http://www.booktv.ch 2015.

[13] An exhibition brochure for My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class) that includes a transcription of all the quotations printed on the curtains and their sources, Reynaud-Dewar’s seminar bibliography, and the original version of this text, can be downloaded from the Audain Gallery’s website: http://www.sfu.ca/galleries/audain-gallery/LiliReynaud-DewarMyEpidemic.html

[14] Critical reflection on the relationship between exhibitions held in the Audain Gallery and the social, economic and political conditions of the surrounding downtown, Gastown, Chinatown and Downtown Eastside neighborhoods are frequently raised, in particular because the gallery is visible to the street via a wall of windows, creating a permeable skin between material and symbolic realms. Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts’ lease in the Woodwards redevelopment has also propelled gentrification and increased displacement and precarity in the neighborhood.

[15] I want to acknowledge Althea Thauberger and Jayce Salloum in particular, for their questions and comments within this discussion.

[16] I want to acknowledge Phanuel Antwi and Denise Ryner in particular, for their precipitation and contribution to this part of the discussion.

[17] Art AIDS America. Curated by Jonathan David Katz and Rock Hushka. Tacoma: Tacoma Art Museum. 3 October, 2015 – 10 January, 2016.

[18] Kerr, Ted. “Erasing Black AIDS Histories.” The New Inquiry. 1 January, 2016. http://thenewinquiry.com/features/erasing-black-aids-histories/

Amy Kazymerchyk is the curator of SFU Galleries’ Audain Gallery. Previously she was the Events + Exhibitions Coordinator at VIVO Media Arts Centre, where she also programmed the Signal + Noise Media Arts Festival. In 2008 she initiated DIM Cinema, a monthly evening of artists’ moving images at The Cinematheque, which she directed until 2014.