Pat Badani

Entrée

Spanning three decades of engagement with food in artistic research-creation, I’ve steadily explored networked ecosystems and entangled becomings expressed through narratives of care. Interweaving different connections, forms of knowledge and sensitivities, the artworks complicate the role of matter in determining form and meaning. Imagining and visualizing ecological systems in which humans and non-humans might engage sustainably, the artworks attempt to register and activate the affective everydayness of life, replete with uncomfortable realities and conundrums – recognizing complexity, uncertainty and hope.

The current essay discusses a dozen projects incorporating food created between 1994 and 2020. An attentive study of material worlds has led me to question how matter and meaning are entangled in the so-called subject, the so-called instrument, and the so-called object of research. Seen as artistic arguments blending aesthetics and criticism, each project has involved a repositioning on my part as the knowing subject. Aware of the complexities involved, the material form adopted in each project is indicative of the evolving relationship between art, technology, science, society, its objects and its subjects.

Drawing connections between theories related to art as object, art as medium, and art as critique of political and technological networks, the projects reveal how these ideas have evolved in my practice around the following questions: How do my artworks allow objects to speak, and what do they say about perceived utopias/dystopias? What is the cultural significance of the materials chosen? What are their histories and affects? Are they representative of specific kinds of labor or industry? How have new technologies reconfigured my research-creation? How do my works engage notions of agency and vitality of the non-human realm? Last and not least, cognizant of theories addressing the unique ontological and ethical challenges concerning a looming ecological collapse, how do my works respond to new discursive registers?

Something to chew on

Vegetables and fruit in art and their status as inanimate subjects that the artist organizes into a composition exemplify –throughout art historical periods– the progress of ideas, the use of new tools and techniques, and the desire to know through the study of the everyday. In the twentieth century the use of food in art becomes a suitable instrument for avant-garde artists in search of new forms, and representations of vegetables and fruit are seen to cross the whole of the century from surrealism to pop-art (where depictions of foodstuffs are often used to denote consumer society), not to mention the use of food in staged photography, in the moving image, in 3D computer generated images, and last but not least, in community art and in social media where meal photos promoting an array of eating habits become emblematized in the ‘food selfie’ phenomenon. Furthermore, the reassessment of our relationship with the material world prompted by developments in quantum physics showing that matter we previously thought of as ‘inert’ is in fact made up of vibrating strands of energy – prompts a revision of relationships between matter and materials. Correspondingly, connections with the material world are stretched or ruptured in art. Then, “Live” bio-art that often combines the aesthetic and the artistic with organic, often living matter, further complicates this association. These practices reflect the progression of ideas linking art, technology, science, society, its objects and subjects; ideas that embody moral, economic, and social codes of meaning, and which offer me a reflective handle to think about how the ‘material’ intersects with the ‘aesthetic’ in numerous projects that I’ve created since the 1990s.

Food is integral to existence yet its manipulation since the Industrial Revolution has caused the world’s greatest imbalance. An investigation into discourses driving nutritional diets from WW2 to the present, has led me to evaluate the quest for mastery over bodies and environments – behavior conceptualized through ideas of progress, beauty, domestication, and profit. These ideas permeated by the dominance of humans over non-humans – supported by systems like the agricultural and food processing industries – have resulted in the collapse of ecologies large and small. Additionally, in my quest to understand the changing status of the art object in my work, my research has led me to ponder over issues of materiality, and how new configurations reveal the intimate connection between the material conditions of a society and the forms of art that are produced in it.

The projects discussed below, incorporating food, exemplify changing practices – form material engagement in sculpture and installation to digital media (an arguably ‘dematerialized’ form) to Live bacteria. The connective thread running through them is an attempt to reconcile notions of alterity by making visible the vulnerable encounter between variable forms – be they organic or electronic. Using food as material and subject, my search is driven by concepts such as social disparity, climate change, creature welfare, and food inequality–with plenty more “on my plate.”

From creating worlds of bread to cultivating friendships with mold spores, these projects explore how cultures intersect with each other around notions of a ‘better-life’, using food to more fully understand worldviews through the lens of a ‘dietic utopia/dystopia’. By means of photography, sculpture, media installation, 3D computer animation, graphic and interactive design, culinary arts, creative writing, and book arts, food-associated projects examine subject positions and webs of intersections between humans and non-humans; exposing tensions between corporate dictations of the ‘good life’ contrasted with worldviews that resist subjugation of bodies and lands.

Pat Badani, Borderlines with Snake, 1997, Staged photography, bread-bowls, rope. Image courtesy Pat Badani.

Hors d’oeuvre(s): hot, cool, glitched, and moist

In Tower Tour and Borderlines (1994-97), I created a world of bread out of a Parisian bakery. A civilization of flour and yeast, my baked society came complete with ecological catastrophes and techno-futurist renewal. This led to the exploration of an interactive and participatory world in Home Transfer (2000-2002) where networked structures and a codified online architecture allowed global migrants to redefine notions of ‘home’ and ‘touch’. Next, AL GRANO (2010-2016) used the corn seed as symbol of Mesoamerican history and culture. The project highlighted forgotten native histories and connected Maize culture to today’s debates about foods containing GMO corn. With elements ranging from a mobile app to Glitch Art to integrated Latin American manifestoes, projects exposed diverging power relations: one that considers food symbolically and one that considers it a commodity. Continuing to explore food, in 2016, I cast a critical eye on the food web and consumer-resource systems with Comestible, a multi-part project. It includes Comestible Process Promise, a work that matches images of industrial foodstuffs (whose methods of mass production adversely impact ecology) with environmental counterparts. In Comestible Fortune Chocolates, I made candy containing slips of paper with presumed truisms about eating habits, parodying Instagram ads falsely representing beauty, dreams, or better life. Then, in another installment of my survey into how ‘nutrimental’ structures spread through networks and shape ecosystem, @Comestiblemealplan incorporates an interactive Instagram-based archive problematizing narrative that animate the voracious circulation and consumption of food images in social media.

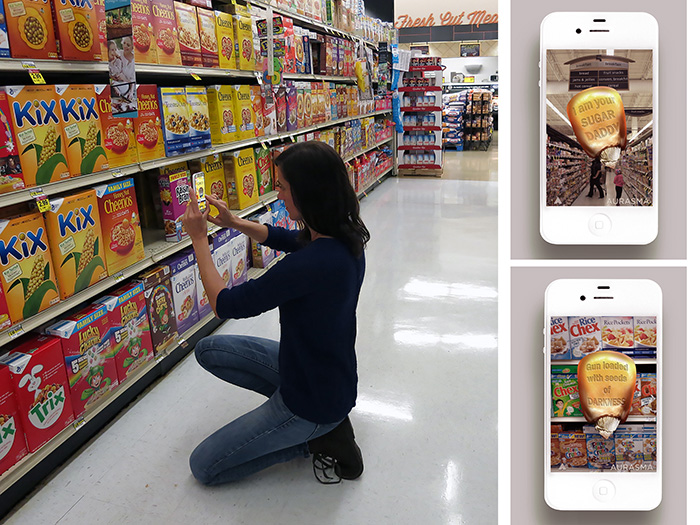

Pat Badani, AL GRANO: Augmented Cereals, 2016, Intervention in a supermarket using an Augmented Reality app for smartphones & tablets (AURASMA). Image courtesy Pat Badani.

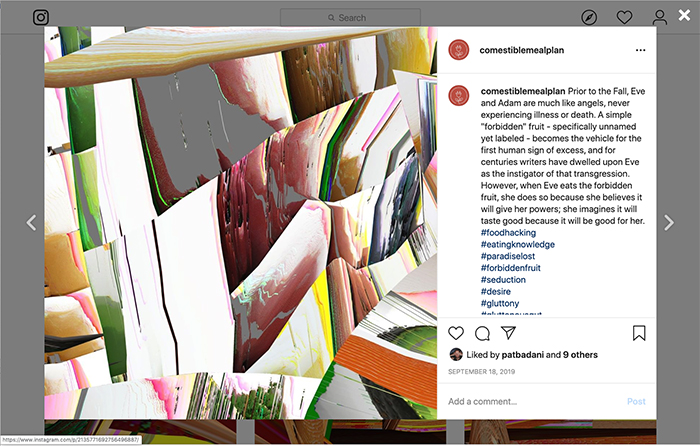

Pat Badani, @Comestiblemealplan, 2019, Screenshot of the interactive Instagram platform. Image courtesy Pat Badani.

Further, my 2020 artist’s book Comestible 7-Day Meal Plan: Food as Text is an illustrated manifesto for cultural change in which I playfully embed geopolitical, environmental, labor, and economic narratives into 7 recipes to be ‘digested’ in the mind. Currently, in a DIY bio science work titled Comestible Colonies, I involve culturing bacteria and deliberately invite microorganisms to propagate and flourish. Like in an alchemist kitchen where substances continually act with one another to shape new things, these works are in transition. They unfold through different states of transformation, and in turn, my observation of these phenomena propagates ideas for new artworks.

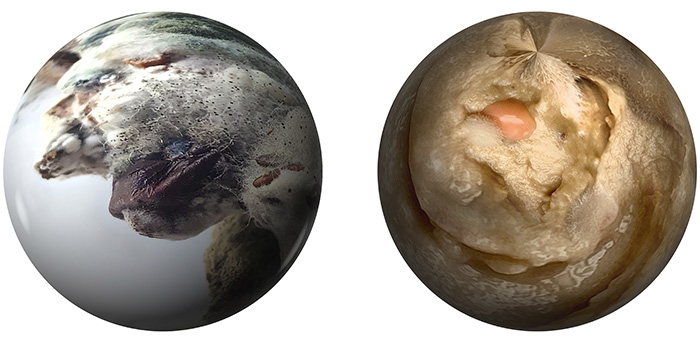

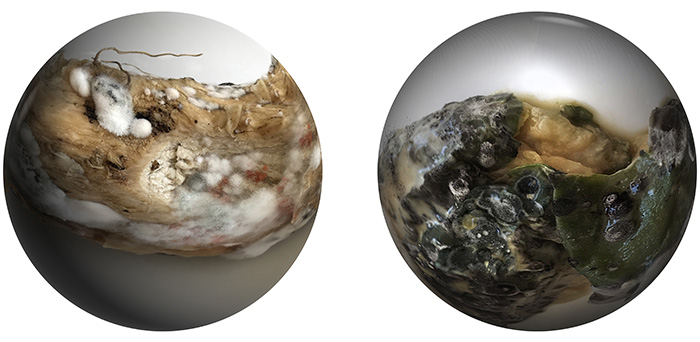

Pat Badani, Comestible Colonies, 2019-2020, staged photography of molding vegetables and fruit. Image courtesy, Pat Badani.

Pat Badani, Comestible Colonies, 2019-2020, staged photography of molding vegetables and fruit. Image courtesy, Pat Badani.

Life & In-digestion in Eden

One of the major questions of our day is how the array of existing world species will be transformed by rapidly changing conditions as humans continue to alter ecologies and to design new life-forms through artificial life, synthetic biology, and genetic engineering. Whether officially regulated, or unregulated –as with the push by biohacker groups to democratize regulation– complex human-made systems of technology and economics often cross safety lines, moral lines, and ethical lines in order to produce bioproducts used in different fields like agriculture, environmental remediation, and healthcare. These human-made systems have a nature of their own – they combine and evolve with biology, catalyzing debates on emerging biotechnologies and the consequences of their fabrications. Correspondingly, the march of biological discovery and the reshaping of ecosystems have spawned new debates about the origin of life and the levels at which knowledge or consciousness exists; about what is regarded as distinct ‘species’; and about the understanding of ‘evolution’. In this context, the definition of ‘Life’ and its unfolding is seen as dynamic – crisscrossing the former divide between the living and non-living, the organic and inorganic, the human and nonhuman, growth and decay, life and death. The need to analyze this rapid development in sciences and technologies and the ways in which they are reconfiguring modes of socialization and subjectivation, provide opportunities for experimental artistic approaches that reveal, speculate and expand upon the issues involved in current mutations; a challenge that I explore in the ongoing, multi part, Bichi project.

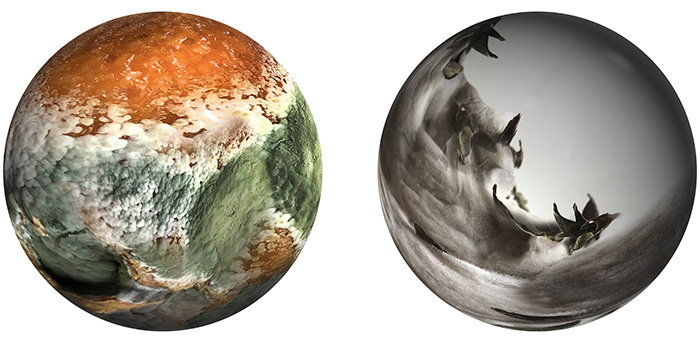

Pat Badani, Comestible Colonies, 2019-2020, staged photography of molding vegetables. Image courtesy, Pat Badani.

Raw ++ Recycled

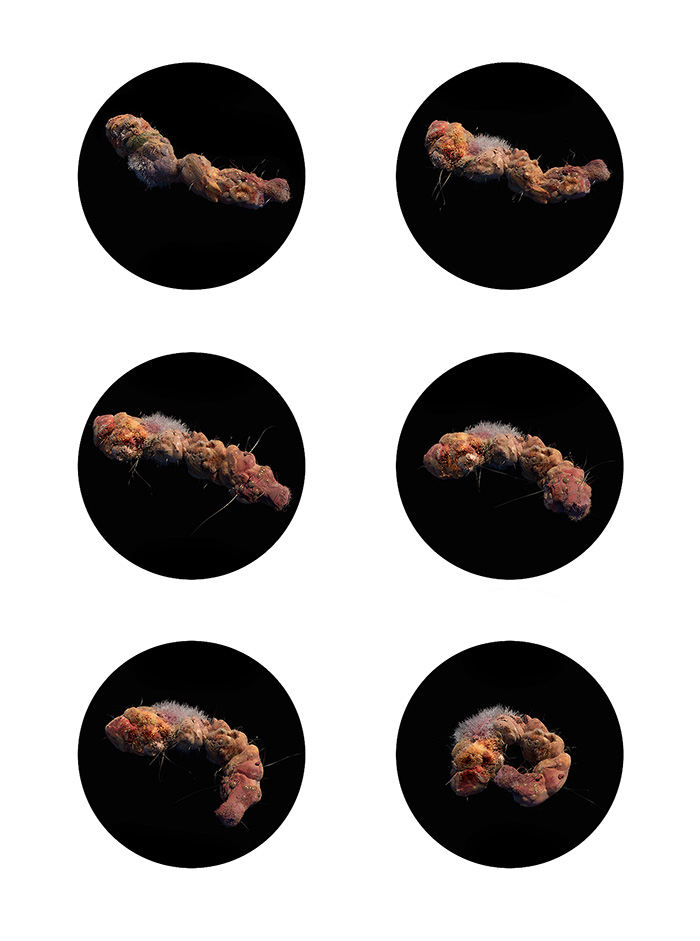

The series of DIY bio forms that grow in an incubator (figures 04, 05 & 06) enable me to study natural processes that, through time, create entities that defy categorization. A bio-based symbiotic interaction unfolds as mold grows and takes over decaying vegetables and fruits that become necessary nutrients to keep microorganisms alive, creating transspecies assemblages. Living and dying, growth and decay, overlap in the space and volume of the contaminated foods. Although the decaying vegetables and fruits are rendered inedible for humans, the death of the organic tissue is accompanied by the thriving growth of the infecting bacteria, mold and fungi, suggesting that different bodies, organisms, and species are in the process of becoming with each other through ongoing negotiations. The work involves interconnections between three actors: disintegrating vegetable matter (the sculpture’s material), thriving recycled matter (bacteria, mold and fungi), and an ecological facilitator (me). With the aim of reinterpreting subjectivities and positions about who/what has the right to exist and thrive, the organic sculptures underscore interconnections and mutual dependence between different organisms and species, perhaps raising ethical questions about whose wellbeing is actually being met.

My observations of the mentioned natural processes enable the evolution of ideas through responding to matter. One could argue that a recycling process is involved – a process whereby ideas and matter are constantly composed, decomposed and recomposed, and in which my observations are converted to representations of the sentient. Three works are nested in the Bichi media installation and the artistic procedure is layered. First, the organic foodstuffs and microorganisms are photographed at evolving stages of composition and decomposition. While the bio forms are dynamic sculptures of live matter, the photographs enter the domain of image-making. Next, both live sculptures and still photography provide a framework for several digital simulation works developed with 3D computer modeling software, further reconfiguring the relationship between material and immaterial processes.

Pat Badani, Incu-Bichu, 2020, 3D computer graphics. Image courtesy, Pat Badani.

Le Crédible (The Credible) in Incu-Bichu ++ Bichicuchitu ++ Bichicu-Chow

Fungi can be found in every pocket of the globe, with substances continually acting with one another and creating networks that shape life – a development that my DIY bio-forms enable me to sample, observe, and document. Incu-Bichu, Bichicuchitu, and Bichicu-Chow give form to my ensuing reflections.

These works nested in the installation titled Bichi present the viewer with imaginary, hypothetical organisms, offered for examination and contemplation as in a scientific display. The uncanny photorealistic 3D renderings are intended to amplify cognitive dissonance in the viewer by suggesting provisional boundaries between entities, organisms, and species. The works make visible and believable what has not yet been accounted for in order to draw attention to life-functions presumed to take place through their entwinement with science and technology. Inspired by factual/fictional narratives about sentient species and the rarity of ecosystems, the Bichi artworks underscore processes associated with cycles of living and dying, composition and disintegration, growth and decay, and adaptability and resilience.

Pat Badani, Bichi installation, 2019-2020, Model looking through a viewer displaying one of the works in the media installation. Image courtesy Pat Badani.

Pat Badani, Bichicuchitu, 2019-2020, Stills from the media installation. Image courtesy Pat Badani.

Pat Badani, Bichicuchitu, 2019, 3D animation, 3:33 duration shown in an infinite loop. Acknowledgement: Mueol Choe assistant 3D Animator. Video courtesy Pat Badani.

An ecosystem is a community or group of living organisms that live in and interact with each other in a specific environment. In a healthy ecosystem, populations interact in balance with each other and with their environment, and taking energy from the sun, decomposers break down substances, returning and recycling vital nutrients. For this to work, each step in the food chain must contain an appropriate number of organisms; but if this chain becomes unbalanced, the likelihood of ecosystem collapse is increased. For example, too much algae blocks sunlight from reaching plants; too few plants mean less food for herbivores; less herbivores means less food for primary consumers, and so on. Currently, the rapidly accelerating loss of plant and animal life on planet earth can be largely attributed to human population pressures and to the demands of economic development. Many species are at risk of extinction because of human activity, changes in climate, and changes in predator-prey relationships that result from introduction of species native to some other part of the world, not to mention the potential risks behind experimental synthetic ecology. Reflexivity based on these concerns shape aesthetic expression in Incu-Bichu, Bichicuchitu, and Bichicu-Chow.

The time-based animations nested in the Bichi installation are crafted with 3D computer modelling software and extend photographic image-making in a complex durational procedure –a creative collaboration with DIY science and technology. The passage from one to the other in the constellation –live sculpture, digital photography, and 3D computer simulation– reveal differentiated yet interconnected aspects of artistic creation that expose the porousness of boundaries between what might appear as separate entities—subject/object, fact/fiction, science/culture. They involve evolution of new forms that, through transition and transposition, unfold expressive intensity that not only intermingles boundaries but also highlights the role of technology in fathoming emotion in new forms of visual narratives. In this regard, I see art as tool for mediation of knowledge about complex phenomena occurring in times of uncertainty about the future triggered by climate change and ecological crisis.

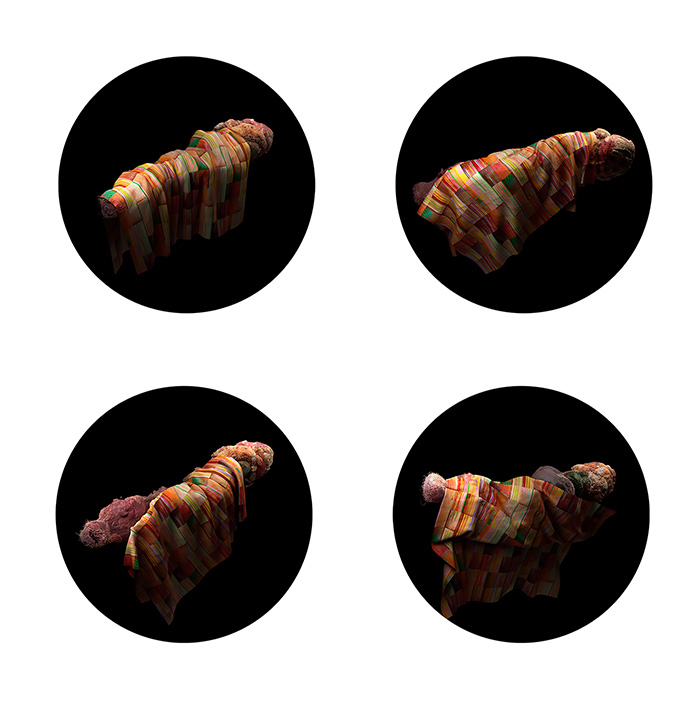

Art is based in the action of artmaking and rooted in both the transformational and the transmutational challenges related to both form and matter. For me, the action of artmaking is like cooking in an alchemist’s kitchen – literally so because many of my projects are born in my kitchen and further developed in other environments and mediums in a process that involves assembling and collecting things together, witnessing rupture or disturbance, and remaining open to unexpected events in order to gain new access to the real. Through the ‘testing’ process, ideas, substances and mediums are continually ‘boiled down’ and remixed. I then separate them and re-mix them again to see how they react with one another and shape new things. For example, as part of this practice and in another ‘recycling’ instance that shows how one project informs and becomes part of another, the patterned cloth covering Bichicu-Chow is taken from @Comestiblemealplan, my Instagram archive of Glitch images in which I re-codified data driving digital images of industrially produced food by inserting texts from literary sources that highlight the role of women in food cultivation, distribution, and consumption: Paradise Lost (Milton, 1667), The Edible Woman (Atwood, 1969), and Como Agua Para Chocolate (Esquivel, 1989). This remixing is more than mere reorganization, it involves a montage that reveals associations, fissures, differences and similarities brought together to form a complex fabric. Matter is not passive, and it matters.

Pat Badani, Bichicu-Chow, 2019-2020, Stills from the media installation. Image courtesy Pat Badani.

Pat Badani, Bichicu-Chow, 2019, 3D animation, 3:33 duration shown in an infinite loop. Acknowledgement: Mueol Choe assistant 3D Animator. Video courtesy Pat Badani.

Biblography

-Braidotti, Rosi, “A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities”, Sage Journals, Theory, Culture & Society, University of London, (2018), Vol. 36 issue: 6, page(s): 31-61, accessed July 28, 2020.

-Bowler, Peter J., Evolution: The History of an Idea (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, U.S.A., 1989).

-Boyd, Madeleine, “Multispecies in the Anthropocene”, Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, Spring Issue 31 (2015).

-Gonzalo, Julio Antonio & Manuel M. Carreira, “Intelligible Design: A Realistic Approach to the Philosophy and History of Science”, Singapore, World Scientific Publishing Company, 2013).

-Latour, Bruno, Reassembling the Social – An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, UK, 2005).

-Mackenzie, Pamela, “Art History and the Matter of Materialism: Networks, Things, Objects and Ontology” (Syllabus, University of British Columbia), Academia, accessed August 1, 2020)

-Mersch, Dieter, “Alchemistic Transpositions: On Artistic Practices of Transmutation and Transition” in Transpositions: Aesthetico-Epistemic Operators in Artistic Research, (Michale Schwab, Ed., Orpheus Institute, Leuven University Press, Belgium, 2018) 267-279.

-Radomska, Marietta, “Transspecies Assemblages (2012)”, in Uncontainable Life: A Biophilosophy of Bioart, (Linkoping, Sweden: Linkoping University, Department of Thematic Studies, 2012) 123-153.

-Raymond, Martin; Chris Sanderson; Gwyneth Holland, Create. Eating, design and future food: The Future Laboratory (Berlin, Germany: The Future Laboratory, Published by Gestalten, 2008).

-Rowell, Margit, Objects of Desire: The Modern Still Life, Exhibition catalogue and book. (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1997).

-Stock, Adam, “Making Art in Dystopia”, Alluvium Journal, 1.3, August 2012, Durham University, Durham, UK. Accessed July 28, 2020)

-Sützl, Wolfgang, Theo Hug (Eds.), “Activist Media and Biopolitics: Critical Media Interventions in the Age of Biopower” (Innsbruck, Austria: Innsbruck University Press, 2012).

-Whitefeather Hunter, Biomateria: Biotextile Craft (Montreal, Canada: Concordia University FOFA Gallery, 2015).

-Zinser, Maria, “A Very Brief History of Still Life”, Sotheby’s 19th Century European Paintings, April 18, 2017, accessed July 28, 2020.

Pat Badani is a visual artist, writer and researcher who explores notions of utopia and dystopia through emergent art practices. Her artworks have been showcased in international festivals and symposia: ISEA; Transmediale; New Forms Festival; ELO (Electronic Literature Organization); Currents; FILE; Festival Internacional de la Imagen; Art Souterrain; Balance-Unbalance; and in venues such as Espacio Fundación Telefónica, Argentina; New York Hall of Science, USA; Guggenheim Gallery Chapman University, USA; Tarble Arts Center-Museum, USA; Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts, USA; UIUC iSpace Gallery, USA; Musée de Bas Saint Laurent, Canada; NSCAD Anna Lenowens Gallery, Canada; Canadian Cultural Center, France; Maison de L’Amerique Latine, France; FRAC Corsica, France; Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico; Museo Universitario del Chopo, Mexico; Museo de Monterrey, Mexico; MECAD\Media Centre of Art & Design, Spain; to name a few. She has received over twenty awards and commissions including a media arts research-creation grant from the Canada Council for the Arts for her project “Where are you from?_Stories” exploring the utopian imagination in human migration; support from the “Robert Heinecken Trust Fund” for her project AL GRANO investigating the dystopian impact of GMO corn on maize in Mexico; a DCASE award and a National Endowment for the Arts MacDowell Fellowship for her project Comestible in which she surveys dietic utopias/dystopias in contemporary food-diets. In 2018 she was nominated for an AWAW merit award recognizing women of creative vision in the USA. In 2020 her work was recognized by the Electronic Literature Lab for Advanced Inquiry into Born Digital Media alongside other international e-lit women pioneer and visionaries. Badani has participated in conferences with her essays and talks in over 15 countries. Essays and reviews examining her works have been published in three languages in international solo and group exhibition catalogues, in thematic anthologies, and in journals.