Jondi Keane and Katie Lee

The embodied practice of cognitive reading

From a creative practice point of view, it would be fair to characterize the cognitive turn[1] as one that has universalized and naturalized how thought and experience are understood. However, this tendency works against cognitive readings produced through creative arts practice (also described as creative practice research, research creation and practice-led research), which are embodied, situated, distributed and enculturated. If we accept that reading the world through the lens of cognitive theories is an aspect of, and the product of, the complex creative practice research environment, then these embodied practices of cognitive reading must be at the forefront of discussions of Australian art’s impact upon social affect.

We would propose that cognitive reading, that is a search for evidence of embodied orientation, is in fact a cultural practice sensitized to affect. The affects of distributed awareness and attention, as they come to bear upon social-cultural-historical relationships and artefacts, inflect the direction of change, formation and reception of material ecologies. Whether the practices emerge from within a community, a national culture or a research culture, the way in which we co-construct our shared environment cannot be separated from the contexts in which they arise. Environments in this instance are dynamic systems in which the processes of affecting and being affected, play out. It is this notion of affect, as a non-personal field event rather than an aspect of individual psychology that will prove useful for our discussions.[2]

In ‘The Translator’s Foreword’ to Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus (1987) Massumi projects an image of the sustained intensity of affect, which is an accurate description of field events and applies to the way affect theory and enactive theories of cognition operate. Regarding the intensity of plateau activity, Massumi states ‘The heightening of energies is sustained long enough to leave a kind of afterimage of its dynamism that can be reactivated or injected into other activities, creating a fabric of intensive states between which any number of connecting routes could exist.[3] The afterimage becomes a useful lens in attempting to perceive how art has the capacity to inflect the tendencies and selective processes of cognition.

This paper will draw out, emphasize and articulate the ways that arts research is informed by and can inform the study of individual, interpersonal and social cognition, affecting in turn the relationships that congeal as the social. In particular, we propose that the reflective practices of art researchers find affinity with enaction, or enactive theories of cognition, which emphasizes body-environment relationships, dynamic systems and cognitive ecologies. This framing offers insights into the formation and dissipation of affective fields[4] around the intersection of artistic and scientific approaches to embodiment. It is our contention that practitioners of arts research are drawn to cognitive research because, taken in tandem, these two modes of enquiry set up a direct relationship between the feeling / experience of what is happening (art research) with descriptions of what has been or is happening (cognitive research). The first part of our tandem equation focuses on feeling and experience, proposing that practitioners extract concepts to construct creative methodologies and, in doing so, art research participates in the construction of the environment with which it engages, observes and studies. This suggest how an affective field forms and can be identified as an event-space in which multiple actants and processes inter-act. Through deliberate and tacit actions, a field of relationships is established and reinforced or held in place. In other words, a network of connections is co-selected and arises as a function of degrees of affectivity.

Philosopher of cognitive science Ingar Brinck notes, ‘… interactive forces make processes unfold over time, while cognitive processing is analyzed as continuous state change in coupled systems. An individual cognitive process is described as the set of possible ways in which the process can develop in a space of possible trajectories.’[5] This notion of cognition aligns with the ethos of art practices and we propose that the coupling of systems is what constitutes practice (cultural and creative); and the attentions, selections and decision-making processes that arise from such couplings are what art practice makes available for use by a community. The cognitive readings of Australian culture for which artists search and research, petition and re-petition, enculturate practices in an effort to produce the conditions for possible trajectories. These creative practices simultaneously read and contribute (write) new trajectories using performative and responsive approaches. These remain agile to affective and changing states, and in so-doing they are able to capture the lived experience of cognition- rather than to presenting fixed states of knowledge that are impervious to other affects and contexts.

Philosopher Evan Thompson, advocates for the re-imagining of research projects to account for the way that creative practitioners contribute to cognitive science. At the end of his 2016 keynote address at the Body of Knowledge: Embodied Cognition and the Arts conference, he concluded by suggesting that creative practitioners: ‘… embody a kind of expertise; the practitioners embody a form of expertise that is itself a form of investigation and research and that needs to be on an equal footing with cognitive science because the tendency in our culture is to valorize and prioritize the science and I don’t think that is going to do justice to what we want to do.’[6] He identifies the tension between neuroscience and enactive approaches as one that inhibits understanding the dynamic properties of cognitive systems and the interrelationship between body, person and environment. He calls for the abandoning of neuro-centric or neuro-scientific approach to cognition and the embrace of an enactive approach, or cognitive ecological perspective.[7] Thompson goes on to say ‘the proper level of description for any cognitive function (for example, attention) is the whole embodied subject or person, not the brain area or neural networks; it is unlikely that there is one a one-to-one mapping between particular cognitive functions in particular brain areas or neural networks’.[8] So, while neurological and brain-oriented research provides insights into the way particular embodied processes occur, it is the enactive theories that spark the interests of artists looking to understand the body-environment relationship and prompt them to explore and perform body-environment interventions and experiments to interact with the active condition of embodied, situated and distributed cognition. Affect and social cognition are an important aspect of cognitive ecologies that influence the type and intensity of the connections within a network of relationships and the tendencies of attentions, perceptions, selections and decisions that may emerge in any dynamic system.

The crucial point for a consideration of ‘cognitive readings’ is the emphasis on cognitive ecosystems, and the importance of culture to cognitive ecology in which ‘cultural practices orchestrate cognitive capacities.’[9] Thompson observes that ‘under most conditions, locating cognitive processes at the level of neural networks gets the boundaries of the cognitive system wrong. A better unit of analysis is the coupled and enculturated body-world system’.[10] The crux of the matter for creative practitioners comes back to the question of how one determines the proper unit of investigation and establishes practices through which boundary distinctions are drawn, mapped, superimposed or transposed. Creative practice involves methodologies that explicitly include reflective processes and deliberately confront the problem of embedded cultural practices as a way to attend to the wavering affective lines between inside-outside, body-environment, individual-collective, human-non-human, etc.

One affinity that art researchers have for cognitive research in the Australian context is through the early adoption of the creative practice PhD, relative to Europe, North America and Asia. Artists who undertake a practice-led / practice-based research degrees are keenly aware and explicitly asked to reflect on the problems of languaging experience. Although there is a global trend towards creative research PhDs, there is a marked difference in their histories and the positioning of the creative work in the research as seen when comparing different models, for example, in Canada[11] and Europe[12]. Australia has been a forerunner in creative practice research, recognizing practices and projects that are emergent, process-oriented and trans-disciplinary and operate as equivalent forms of academic research in which creative work is central to the contribution of knowledge.[13] This widely accepted but contested approach has permeated the Australian arts context and artists have come to understand and value creative practices, especially the social, cultural and political impact of art within a research culture and Australian culture more broadly.

When discussing the challenges creative practice research presents, Ross Gibson, professor of creative and culture research at the Australian National University explicitly refers to cognitive awareness, observing that:

… the creative researcher engages in a cognitive two-step, jinking rapidly back and forth between immersed investigation leading to inchoate understanding, on the one hand, and reflective knowing outside and after the event, on the other hand. To use anthropological terms, this means the researcher deliberately shuttles back and forth between the ‘emic’ and the ‘etic’ stances (for example, between being an ‘participant observer’ and being a ‘detached scrutineer’) while appreciating the phenomenon under investigation. The cognitive two-step is most readily understood if we can first agree on definitions of what it means to know something and of creative practice.[14] [emphasis added]

As practitioners, we (the authors) want to emphasize this movement—the rapid and paced jinking back and forth within and between networks of relationships—as the key to creative engagement with cognitive reading, which remains open to affective, embodied encounters as they occur (live).

There are two aspects to the way art practice may contribute to cognitive reading of culture. First has to do with the way knowledge is acquired. The second is the uses to which the information is put (this includes sensations, experiences, insights, data and judgements) which specifically result from the embeddedness of creative practice research in the practices of everyday life. This second issues goes the heart of the contention around whether creative practice constitutes research and generates knowledge by asking: what counts as knowledge; how is knowledge measured (for example, invariance) and how does research participate in the production of the world—are questions that art research directly addresses.

The value of creative practice resides not only in the different ways in which knowledge might be acquired (performatively and materially) but in the production of possibility and new domains for thought-feeling-action, which Enactive theories of cognition[15] and Affect theory[16] allow. This approach prioritizes the production of difference that cannot be separated from life or quarantined from the research, rather than the science driven search for invariance. Techniques that support this approach range from the material and craft-based processes, to immersive and technological, to the pataphysical and speculative. Most all techniques value experiential learning, experimental exploration of site and material. Techniques include ‘cleaving [to adhere (to) / to divide (from)’,[17] ‘cutting together-apart’[18] and catalyzing the ‘adjacent possible’.[19] The resulting domains are both representations (objects/artefact) and prompts (actions) that emerge as a function of movement and the quality and specificity of movement/s in a network of relationships. Placing the boundaries that determine the unit of investigation requires movement across embodied processes; attention, perception, selection, decision judgment; which cascade and trickle down into daily practice. If it is possible to identify the ‘unit of investigation’ for creative practice, we would nominate the organism-environment. Because the boundary condition of an ecology are dynamic, the development of an affective field is cumulative and collective.

Exaption: Tracing Affects on the Evolutionary Scale

The ways in which art participates in the collective construction of embodied and social cognition, ecological dynamics and evolutionary processes, is by embracing complexity and cultivating the production of difference which become part of the world being studied. the crucial role of sense-making point to the need for an expanded and more robust set of indicators to account for the ways systems develop. This is perhaps why learning and research initiatives have added and “A” to their acronyms to include non-linear, non-causal factors. The 4EA school of cognition added Affect to Embodied, Enactive, Embedded and Expanded cognition and STEM added an “A” to include Art in Science, Technology Engineering and Mathematics to produce STEAM. As a result of such modifications, research cannot be separated from cultural production. It is for this reason that contemporary art practices point to emergence. The most far-reaching and speculative image of emergent forms, behaviours and ecosystems, is the concept of preadaptation in Darwin (1859) re-interpreted as exaption in Gould and Vbra (1982).[20] For artists this concept projects an image of unanticipated consequences of selection/co-selection processes, in which we are always participating and already implicated. Gould and Vrba explain pre-adaptation or exaption as the situation in ‘… an appropriate environment, a causal consequence of a part of an organism that had not been of selective significance might come to be of selective significance and hence be selected. Thereupon, the newly causal consequences would be a new function available to the organism’.[21] In formulating how a system might develop into its ‘adjacent possible’ Kaufman suggested that evolutionary theory needed to account for both self-organisation and selection.[22] We would argue that the conditions for selection have an affective dimension, which cultural production, and art in particular, perceives as a powerful catalysing agent. For creative practitioners rich descriptions provide prompts and techniques through with to engage with the world and direct cognitive readings. However, they also prompt pataphysical imaginings and an ethos for through which to understand co-selection and the allure of the unanticipated but meaningful consequences that practitioners explore.

It is not possible to know all of the human traits and features of the environment that may emerge from co-selection and participatory sense making[23] as when an ancient organism selected the traits for an eye before it had need for an eye. However, through the use of storytelling, pataphysical imaginings, reflective experiential learning it is possible to speculate the on the condition that might re-orient our attentions, selections and decisions. Through this ethos, art research might be considered the science of our own fiction, forming cognitive ecosystems extrapolated from current knowledge. Cultural images depict larger changes at the evolutionary scale of cognition not perceptible in human time frames. Scenarios played out for mass consumption can, at times, offer techniques for living, constantly attuning to networks of relations/relationships.

Examples in Creative Practice

Critically, the cognitive ecosystems to which artworks can draw our attention exceed the boundaries of the work itself. This can operate through language and story-telling, with narratives and meta-narratives exposing the ways complex systems parallel and intercept our lives; or through creative arts practices that reveal exaption-in-process as key to the conceptual framework. In the following section we will refer to both these strategies—beginning with Wim Wenders’ 1991 film Until the End of the World,[24] based on the collaborative screen play with Australian writer Peter Carey, which contains the confluence of several images relevant to this discussion. Films are micro-societies whose cognitive ecology is focused on the production of an outcome with impact. Wender’s film depicts and enacts the crossovers between collective sense-making, social affect and evolutionary inflection points, in which exaptive traits, selected but not activated, provide new human capacities. Art is precisely the selective process that activates affect as an evolutionary factor.

Until the End of the World begins with images of Australia as the ‘end of the world’. This reference is spatial but also ‘beyond time’ with the evocation of the dreamtime. The outback is the quintessential image of the place of intense reflection and the Dreamtime is the ultimate image, embedded in 75000 years of continuous culture and time immemorial. The screen play [story, narrative] acts out two different trajectories, both of which imagine cognitive transformation. One trajectory is traced by the protagonist Claire’s pre-adaptive cognitive ability and connection to her own cognitive processes via innovative technology. The other trajectory is cognitive transformation through the deep connection to storytelling, which links us back to community and social constructed cognitive ecosystems.

The story unfolds through the different approaches to self-invention. A brief discussion of a few of the characters pertains directly to cognitive transformation. The character Sam Farber (William Hurt) records and ‘translates’ brain impulses encoded through his visual cortex on a prototype camera. However, in order for Edith, Sam’s blind mother (Jeanne Moreau) to experience the recorded vision, the images must be reprocessed through the visual cortex of another person. Sam is unable to successfully act as the translator of the images and asks Claire Tourneur (Solveig Dommartin) to perform the translation. She is able to do this quite effectively, interpreting the captured images through the device so that Edith (the mother) can see the images. This is a clear reference to a kind of exaptive ability of which Claire would not have known she was capable. Claire is able to focus on the relation of memory to images and sensations through an innate embodied know-how. After Edith dies, the technology is then turned towards recording dreams.

The group of protagonists trapped at the end of the world (due to a nuclear fallout) become addicted to viewing and reviewing their own dreams. Eugene (Sam Neill) is an author who is the only one able to escape the allure and addictive qualities of dreams. He ultimately breaks the others’ addiction by telling them stories (as a form of cognitive therapy) which brings them out of themselves. The last images of the film show Claire, who has a new job on a space station, deciphering the weather patterns from outer space. Claire’s character is the image of embodied awareness and cognitive transformation that can be triggered by environmental circumstances unexpectedly rising to the surface and flourishing. This is the very definition of exaption and an ethos of experimental emergent art practice.

More broadly the film is a fable that dramatizes the affects of exaptive potential and the possible movements within and across cognitive dispositions, cultural practices and cognitive ecosystems–such as a lab in the Australian outback, or a globe-trotting film production. In such circumstances, images are made into performative attunements and cognitive movement prompt shifts in enculturated practices. In the next section we will discuss Australian artists who either deliberately engage with cognitive research in order to enable movement within and across the different registers and dimension of representation, performance, perception, action cycles and participatory sense-making or that demonstrate that movement within their work or working processes and methodologies.

Australian practitioners of embodied readings and enactments

Even if a unified law of physics appears, the question of life will not be touched, not because life is concrete and law is abstract but because the law is generally abstract and life is uniquely abstract.[25]

Using cognitive research to think about creative arts practices establishes a parallel framework to reflect upon ways that unique systems of knowledge production can be distributed and held within bodies and attuned to affects that influence how we select and co-select features of an environment. The first artist we will discuss is Muruwari, Bundjalung and Kamilaroi artist Brian Martin.

Martin offers an alternative Indigenous ontology whereby there is no division between the material and the immaterial. This provides access to an expanded particularity of what we think and feel in a present moment, inviting us to re-enter the embodied encounter of the event:

Knowledge is reproduced and preserved as living memory in the performative process of making. In this sense creative arts research is not dissimilar to modes of knowledge production and preservation that occurs in Indigenous culture.[26]

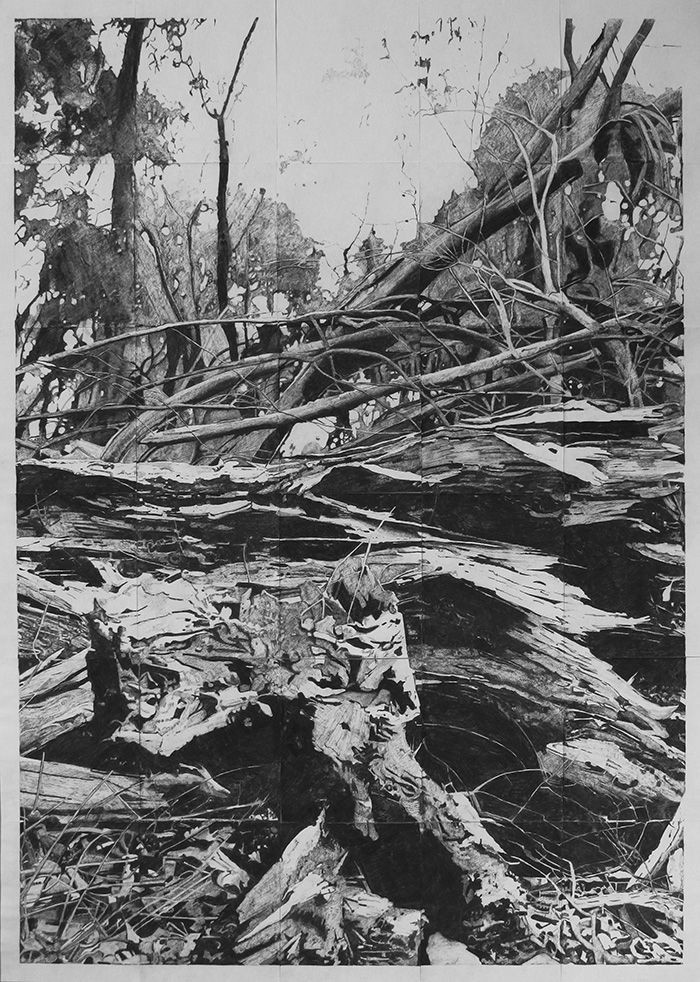

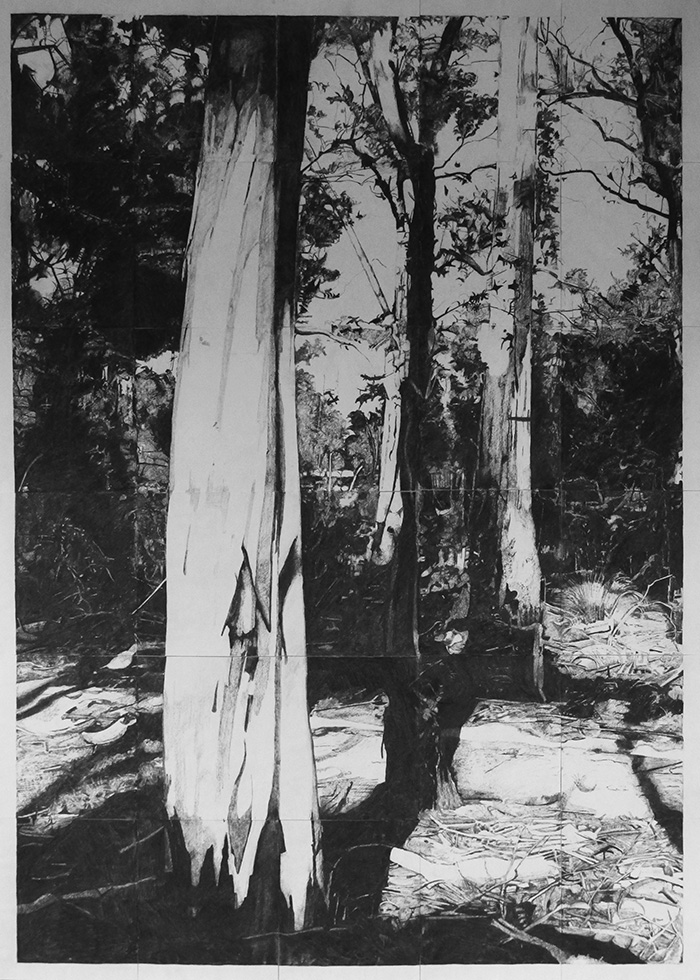

It is precisely this type of movement that represents cognitive cultural ecologies, which Martin extrapolates and registers in his body of charcoal works on paper Methexical Countryscapes. In making these works, Martin describes an active and reciprocal exchange with Country. One that combines his embodied, cultural and historical knowledge of Country with knowledge that he receives from Country, captured through a temporal and performative exchange. Martin says,

The vital point here is that part of this experience is based on the tree or Country imposing its own subjectivity onto me and my own thought processes of looking and feeling the drawings of Country. This is an important aspect of the process as it is the beginning of the journey of making and experiencing and sets up the relationship between Country, myself, drawing, Ways of Being and Ways of Doing.[27]

Rather than representing Country as a scopic image, Martin produces what he calls a ‘diffracted image’, arrived at via various processes of exchange.[28] For example, Martin first travels to Country and spends time there until ‘a tree or part of Country reveals itself [to him]’[29] which he documents with a camera. Upon later reviewing the images, Martin directly ‘re-experience(s) Country’.[30] This exchange enables him to choose an image to work from, which he then enlarges with a photocopier to form a grid of thirty A3 sections. It is only at this point that Martin begins to render the image in charcoal at a 1:1 scale (to the enlargement).[31] This dynamic and reciprocal process requires various layers of cognition and embodied processing, not only of what Martin has captured subjectively, but also what Country has revealed to him in exchange.[32] This reciprocal process allows Martin to capture his embodied knowledge of Country, but also what was always already there, ‘…continually enacting the real relatedness of my existence as opposed to producing an imaginary connection’.[33]

Brian Martin, Methexical Countryscape – Kamilaroi #10, 2017. Photo by Brian Martin.

Brian Martin, Methexical Countryscape – Nuenonne #3, 2018. Photo by Brian Martin.

These processes, although deeply significant and culturally specific, nevertheless tell us something about embodied methods of arts practice that capture cognitive movements. By using the constraint of the camera, the photocopy and the grid, Martin’s practice performs the nesting of culture, body and context, and reveals the indivisibility of person from Country. Martin’s work synthesizes two positions; concepts and knowledge that is embedded within and held by Country, and the subjective, embodied process that he brings to Country. William James concept of radical empiricism is useful here in order to foreground the notion that structures are formed from both experiences and their physical properties. Martin’s process of making his works on paper opens up what James describes as ‘… a that which is not yet any definite what, tho’ ready to be all sorts of whats…’.[34] In Martin’s work this radical empiricism exists in the understanding that there is a physical world (not just his personal experience of it), but that it is layered and impacted by all the other previous experiences and knowledge held by ancestors and in Country. Therefore, Martin’s drawings do not only represent an experience he has had himself, but also (and simultaneously) renders Country as it already was and simply is.

This movement evident in Martin’s work can also be seen in other Australian creative practices, that likewise utilize ‘… resources in the environment and [learn] from the interactions in which they participate’.[35] The next Australian artist whose work can be seen to access parallel cognitive and distributed modes of knowledge is Melanie Irwin, who demonstrates this type of movement in her body of work Spherical Approximations: Geodesic Envelopes. In this series of performative installation artworks, Irwin and various guest performers use sections of framework and furniture that Irwin has re-purposed from objects found on the side of the road. From this tangle of potential, Irwin and her performers attempt to create as close-to-perfect version of a geodesic dome that they can within loosely draped fabric geodesic envelopes. Each performer stands inside these flaccid geodesic sacks, armed with a tangled collection of ill-purposed sections of armature and cotton twine with which to bind it. From discarded Ikea clothing racks, walking frames, chair legs and miscellaneous metal frameworks, each performer somewhat clumsily attempts to first untangle and then reposition each piece in order to form a geodesic super-structure. In fact, there is not necessarily a solution to this self-imposed dilemma. For Irwin, this process is a constant enactment unfolding and expanding what could possibly be. Each performer takes what is to hand grappling with that which is not, but that could be. As Brinck reflects, ‘By exploiting resources in the environment and learning from the interactions in which they participate, dynamic systems can develop complex cognitive processes.’[36] (414). Kauffman’s notion of the adjacent possible[37] is useful when examining Irwin’s work and offers an apt way of describing how Irwin’s works are both made and operate in the contexts and conditions she crafts. As Kauffman says, ‘Every new Actual creates a new set of adjacent-possible pathways or opportunities for further exploration. This holds for space grains evolving in the giant molecular clouds in galaxies, for complex chemistry in space and in the evolving biosphere, for life, for geologies and mineral deposits.’[38]

Melanie Irwin, Spherical Approximations: Geodesic Envelopes (Performance Still 09) Performance with textile membranes and modified metal objects. Duration 2 hours. West Space, Melbourne, 8 August 2015. Performers: Danica Chappell, Emma Collard, Klara Kelvy. Photo by Christian Capurro.

Melanie Irwin, Spherical Approximations: Geodesic Envelopes (Performance Still 99) Performance with textile membranes and modified metal objects. Duration 2 hours. West Space, Melbourne, 8 August 2015. Performers: Danica Chappell, Emma Collard, Klara Kelvy. Photo by Christian Capurro.

The third practitioner is Katie Lee, whose work addresses the notion of the ‘adjacent possible’ by employing the notion of a set. In Lee’s performance installation Set Elements, the set refers to a large number of individually constructed sculptural parts, which are (or at least resemble) functional items; ladders, balls, bricks, brooms, stools, ropes, buckets, blackboards, chalk, blankets, steps and timber brackets and frames. It is the shared potential of these objects that creates the set, offering the possibility that through re/arrangement some kind of order will be revealed, or that this set will eventually resolve and settle. Lee and the performers who work alongside contradict the expected or ordinary use of each familiar object. This is because the score they follow directs the performers to constantly locate and enact the potential or the affordances of the elements in relation, rather than to finalize, complete or literally ‘set’ them. In fact, the score asks that the performers never allow these relations to settle in place (be set). Instead by constantly reshuffling and repositioning elements within these sculptural arrangements, Lee effectively proposes a series of blind trials. With each new set of arranged sculptural forms and objects, any functional relationships between these objects are only held by our preexisting expectation of what these items’ purpose or capacities are, rather than their potential for adaptation. Instead, Lee presents and endlessly shifting constellation of relations-in-action.

The performative actions that constantly separate-out and reassemble the parts-in-relation, reveal the functionality and possible dis-functionality of various of the objects. However, the trials also present new affordances or activities supported by an environment.[39] This playful engagement with affordances, through constant changes and the unpredictability of the other performers’ actions, invites new combinations. While the combinations of objects do not seem to have a particular purpose, the improvised actions are made live, without a predicted or known outcome. While this is true of all improvisation, Lee extends the idea of a known-unknown into an unknown-unknown by having multiple performers also acting unpredictably. At times, two participants might arrive at the same object, and must split and pivot to form arrangements in ways that could not be known to one or the other. Thus, in the practice, Lee and performance guests are constantly in the process of enacting, and this process, apart from short pauses and rests, never resolves or completes.

Katie Lee, Set Elements 2019, with performer Arabella Frahn-Starkie in the exhibition Temporal Proximities curated by Kelli Alred, Melbourne, Australia. Photo by Anne Moffat.

Katie Lee, Set Elements 2019, with performer Arabella Frahn-Starkie in the exhibition Temporal Proximities curated by Kelli Alred, Melbourne, Australia. Photo by Clare Rae.

The final practitioner is Jondi Keane, whose work touches on the varieties of experience evident in the other artist’s work discussed above, concerning participatory sense making and a re-timing of the affective field. That is to say, the focus of Keane’s performative installations draw attention to the elements in play or that are activated in an event-space, and to how the deliberately shifting relationships are recalibrated by attendees and participants. In the exhibition, All that is solid melts into movement (2018), Keane and collaborating artists (Rea Dennis and Kaya Barry) produced multiple installations that focused on built features (such as a gallery wall or a sidewalk) that are usually fixed in place and provide the given conditions of a built environment—and loosened them from their mooring allowing them to move about and participate in spatial, intersubjective and social experiences.

Jondi Keane, Rea Dennis and Kaya Barry – All that is solid melts into movement 2018, Couniuhan Gallery, Brunswick Victoria, Australia. Photo by Kaya Barry.

Jondi Keane, Rea Dennis and Kaya Barry – All that is solid melts into movement 2018, Couniuhan Gallery, Brunswick Victoria, Australia. Photo by Kaya Barry.

The aim of the work is to allow observers and participants to calibrate the way changes in the pre-set conditions of a space affect their own spatial orientation and links to other body-environment experiences. The artist spoke to gallery goers taking the performative position of worker rather than authority, and interviewed people about the thoughts and feeling prompted by the moving elements. One person, who moved the large 3.5 x 3.2-meter-high wide wall on wheels across the gallery floor, talked about an Alice and Wonderland syndrome like that which they experienced as a child. The syndrome, named such because people have the perception and sensation of becoming larger and smaller in a space in rapid succession. In addition to the material, built elements of wall and sidewalk, a video projection compounded the way in which conceptual information interacted with, augmented or inhibited perceptual information. A large-scale video of Kaya walking on boardwalk and bridges was projected near the 1 x 2m section of concrete sidewalk on wheels, which could be reconfigured by participants alone or by impromptu groups. A video of Keane pulling the wall while reading a book and a video of Keane moving walls in relation to Dennis riding a bike formed a large-scale tango—which was projected onto the moving wall. This video would diminish or expand in size as the wall was moved closer or further from the projector.

While importing images of other spatial environments, the projection also served as a spatial measure that the person pulling the wall could use to measure where they were in the gallery space. Ultimately, it is the complexity of the interactions, the opportunity to talk about connections through one’s own body-environment experiences and spatial intelligence that became the artwork. Rather than producing the outcomes of an experience, the work pointed to and evoked expanded possibilities of body-environment experiences by focusing on the conditions of cognition that become naturalized, and even ritualized, in our daily life.[40]

Martin, Irwin, Lee and Keane are just four poignant examples of Australian artists who demonstrate or actively engage with cognitive research, making cognitive readings of their situation and their context at the intersection of art, science and culture. Australia has been engaged in an open and ongoing debate over the last three decades regarding the relationship of art to research. As with for example a PhD degree, by contesting the boundaries of practice-led, practice-based and practice-as-research as a way to explore the nexus of art-life and theory-practice.

Conclusion

The purpose of cognitive reading is not to describe how things have occurred, but aims to move towards an inclusive, non-reductive embodied cognitive science. This approach might replace the linear causation of ‘sense-think-act with sense-act processing’.[41] The concept that a thing can be unto itself, autonomous and withdrawn must be weighed against the notion that things emerge from dynamic systems, to hold relationships in place. Cognitive readings help us to perceive and modulate the extent of different events that influence the field under observation.

The improvised set of relations in Lee’s work, along with the constant searching for the perfection of the geodesic dome in Irwin’s, means that the possibility for new relations and new structures are being enacted and presented rather than re-presented as knowledge that has already been formed and is simply being displayed or shown. The capacity for artworks is to operate ‘live’ at the intersection of historical observation, perception and action, at the scale in which life happens, and in the time frame of human perception. Creative practitioners experiment with holding the maximum variables and extreme conditions of identity boundaries, avoiding where possible the reduction of experience in space or time, and reified re-presentations. Instead, such images become part of a larger set of events and relationships, as affordances nested with the environment. As Thompson notes, the problem is always getting the boundaries right for the study of live/living, not only because any one perspective misses something or because the boundaries are constantly shifting, but because practitioners are also able to experiment with their own cognitive processes and ecosystems, appropriating, circumventing, repurposing, joining and separating the components, qualities and relationships through the movement of our attention and the direction of our actions. This is what the practice of cognitive reading makes available for use—a full set of dimensions of what is there now and what might become.

The artists mentioned do not claim to produce new objects or networks of relation, rather their processes set up the conditions for unanticipated occurrences and forms to emerge. If the emphasis is focused on continuous variation, then contemporary artists turn towards enaction. The precarity of a body-environment relationship cultivate through art, sets up the potential for making possible trajectories, one of which may escape from an old relation and stray into a new evolutionary development as described by Darwin’s preadaptation (1859) or Gould and Vbra’s exaption.[42] Because they always remain in flux and never settle, they are forever unfolding and potentially productive, rife for creative practice.

We propose that the Australian context is unique in the way it forms the network of relationships between different modes of acquiring, producing and enabling knowledge. The movement and the qualities of movement between the embodied acquisition of knowledge–with place, cultural practices and colonial history–informs how the shared environment is co-constructed. At the intersection of embodied knowledge regimes, a site open for movement can be collectively shaped. It is within the collective shaping that movement within and across modes of learning and knowing are sanctioned, inhibited or generated. Creative practice exemplifies an ethos that emphasizes the lived experience of ideas, requiring an inclusive perspective on what counts as knowledge and how research is already embedded and constitutive of the ‘realization of living’.[43] In order to reconfigure relationships, as they persist and emerge, the cognitive readings we construct and deploy must also be the cognitive reading we enact and absorb as a daily practice. As practice shifts the boundaries and tendencies of the body-environment, potentials for action and interaction therefore become modes of co-selection and co-construction.

Cognitive reading (the practice) and cognitive readings (the enquiry) are the enactments of a field of tendencies and events. The alignment of embodied reading and enactments deliberately de-centralises and disperses awareness and attention throughout the construction and relationships we select, distribute and hold in-place. In turn the alignments become attunement and eventually asocial, cultural and historical affinities on possible futures. This occurs as creative practitioners to extract concepts from their original context, activating them in another site and seizing upon those concepts as springboards, provocations, propositions, inflections or questions articulated or vaguely imagined. Creative practitioners constantly trouble themselves over whether or not they are or are not within the boundaries of their own research, and from which cognitive domain they are operating. To stretch and test the boundaries of the practice of embodied cognition ultimately brings social cognition to bear upon cultures of practice in search of ‘what happens next’.

[1] Varela, Francisco J., Pachoud, Bernard and Roy, Jean-Michel (Eds). Naturalizing Phenomenology Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1999)

[2] Massumi, Brian ‘Notes on the Translation and Acknowledgments’ in Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota, 1987), xvi.

[4] Keane, Jondi and Pia Ednie-Brown. ‘Collapse: Clouds of Affective Dust.’ Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22, no. 1, edited by Lanfranco Aceti, Paul Thomas, and Edward Colless. (Cambridge, MA: LEA/ MIT Press, 2017), N.P

https://contemporaryarts.mit.edu/pub/collapse/release/3

also

Ednie-Brown P, Keane J. Collapse. Contemporary Arts and Cultures [Internet]. (2017 Nov 6) Available from: https://contemporaryarts.mit.edu/pub/collapse

[5] Brinck, Ingar. ‘Situated Cognition, Dynamic Systems, and Art: On Artistic Creativity and Aesthetic Experience.’ Janus Head 9 (2), 2007, 407-431, 413.

[6] Thompson, Evan. ‘Mindfulness and Embodied Cognition’ keynote presentation, Body of Knowledge: Embodied Cognition and the Arts. UC Irvine, 6 June 2020, Online video

https://sites.uci.edu/bok2016/, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6&v=rG3daqNH700&feature=emb_logo. Time code 47:27

[11] Manning, Erin. ‘Ten Propositions for Research Creation’ in Noyale Colin and Stefanie

Sachsenmaier (Eds) Collaboration in Performance Practice. (UK, Palgrave Macmillan). 2016. 133-142.

—. ‘Creative propositions for thought in motion. INFleXions, No1, 2008, pp 1–24. Retrieved

from: http://www.senselab.ca/inflexions/n1_Creative-Propositions-for-Thought-in-Motion-by-Erin-Manning-1.pdf

—. ‘10 Propositions for a Radical Pedagogy, or How to Rethink Value’ In Gerko Egert, Ilona

Hongisto, Michael Hornblow, Katve-Kaisa Kontturi, Mayra Morales, Ronald Rose-Antoinette, Adam Szymanski (Eds.) Inflexions Special issue 2015 ‘Radical Pedagogies’, No 8, 2015, 202-210.

Manning, Erin and Massumi, Brian. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience.

(Minneapolis MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[12] Lury, C., Fensham, R., Heller-Nicholas, A., Lammes, S., Last. A., Michael, M., Uprichard, E. (Eds) Routledge Handbook of Interdisciplinary Research Methods. (London and New York, Routledge, 2018).

[13] (Biggs 2018, 2019; Bolt et al 2007; Bolt and Barrett 2007, 2012, 2014, Butt 2017; Gibson 2015a, 2015b, Keane and Barry 2019; Munster 2006; Murphie 2008 and; Oliver 2018).

Biggs, Simon ‘Can we measure the intrinsic value of the creative arts for research assessment?’ Non | Traditional Research Outcomes, (NiTRO, 2019), 1-6. https://nitro.edu.au/articles/2019/6/7/can-we-measure-the-intrinsic-value-of-the-creative-arts-for-research-assessment

Bolt, Barb, and Barrett, Estelle (Eds) Practice-as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. (London and New York, I. B. Tauris, 2007).

—. Carnal Knowledges: Towards a “New Materialism” Through the Arts. (London and New York, I. B. Tauris, 2012).

—. Material Inventions: Applying Creative Arts Research. (London and New York, I. B. Tauris), 2014.

Bolt, B., Coleman, F., Jones, G. and Woodward, A. (Eds) Sensorium: Aesthetics, Art, Life. (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007).

Butt Danny, Artistic Research in the Future Academy.: Intellect, 2017.

Gibson, Ross —. Changescapes: Complexity, Mutability, Aesthetics. (Perth, Australia, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2015a).

—. Memoryscopes: Remnants, Forensics, Aesthetics. (Perth, Australia, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2015b).

Keane, Jondi, and Barry, Kaya. Creative Measures of the Anthropocene: Art, Mobilities and Participatory Geographies. (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Oliver, James. (Ed) Associations: Creative Practice Research. (Melbourne, Australia, Melbourne University Press, 2018).

[14] Gibson, Ross. ‘The Cognitive Two-step’ in Screen Production Research: Creative practice as a mode of Enquiry. edited by Craig Batty and Susan Kerrigan, (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). vii.

[15] Di Paolo, Ezequiel A., Gapenne, Olivier, Stewart, John. Enaction: Toward a New Paradigm for Cognitive Science (Cambridge Massachusetts and London England, MIT Press, 2010).

[16] Gregg, Melissa, Siegthworth Gregory, J. The Affect Theory Reader. (Durham USA, Duke University Press, 2010).

Manning, Erin and Massumi, Brian. 2015.

Massumi. Brian, ‘Introduction’ in Deleuze Gilles and Guattari Félix. A Thousand Plateaus (Minneapolis and London, University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

Deleuze Gilles and Guattari Félix. A Thousand Plateaus (Minneapolis and London, University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

[17] Arakawa, Shusaku. and Gins, Madeline. Pour ne pas mourir. To Not To Die. (Paris, Editions de la Différence, 1987). 44.

[18] Barad, Karen. ‘Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting together apart.’ Parallax, Vol 20 Issue 3:

Diffractive Readings: Onto-Epistemologies and the Critical Humanities, 2014. 168- 187.

[19] Kauffman, Stuart. Investigations. (Oxford UK, Oxford University Press), 2002. 142.

[20] Gould, Stephen Jay and Vrba, Elizabeth, S. ‘Exaption: A Missing Term in the Science of Form’ Paleobiology, 8 (1), 1982. 4-15.

Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species. (London, John Murray, 1859).

[21] Kaufmann, Stuart. Humanity in a Creative Universe. (Oxford UK, Oxford University Press, 2016).130.

[23] De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E.. Participatory Sense-Making: An Enactive Approach to Social Cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6 (4), (2007), 485-507.

[24] Wenders, Wim. (director) Until the End of the World. Warner Brothers Studio, 1991.

[25] Byrd, Don. Abstraction. Unpublished manuscript, 2003, n.p

[26] Martin, Brian. Immaterial Land and Indigenous Ideology: Refiguring Australian Art and Culture. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Deakin University, (Victoria, Australia, 2013). 83.

[34] James, William. Essays in Radical Empiricism. (New York, London, Bombay and Calcutta, Longmans Green and Co., 1912).

[39] Gibson, James, J. ‘The Theory of Affordances’ in The Ecological approach to Visual Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1979, 127-137- p127.

[40] See Stewart, John et al., (Eds) Enaction: Towards a New Paradigm for Cognitive Science. (Massachusetts, MIT Press, 2010).

Varela et al. Naturalizing Phenomenology, 1999.

[41] Shapiro, Lawrence. Embodied Cognition. (New York: Routledge, 2011). 60.

[42] Gould and Vbra. 1982 130.

[43]. Maturana, Humberto and Varela, Francisco, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. (New York, Springer, 1980).

Jondi Keane is an arts practitioner, critical thinker and Associate Professor in Art and Performance at Deakin University. For more than three decades he has exhibited, performed and collaborated on projects in the USA, UK, Europe, Japan and Australia. His research interests include contemporary arts practices, theories of cognition and experimental art and architecture. His creative research consists of studio-based experiments, video and performative-installations. Recent publications include a co-authored book (with Kaya Barry) Creative Measures of the Anthropocene: Art, Mobility and ParticipatoryGeographies (2019 Palgrave), a book chapter in Immediations Anthology (2019 OHP) and has convened the Second International Body of Knowledge: Art and Embodied Cognition Conference (2019 at Deakin University) and co-edited a special Issue of IDEA journal with selected papers from the BoK2019 conference.

Katie Lee is a cross-disciplinary artist whose creative practice includes sculpture, installation, performance, video, sound and drawing. Common to her work is a preoccupation with how our perception of the world around us can shift and flip: from stable to contingent. Her work attempts to reveal and dissect these un/stable relations, along with the various ways that architecture, bodies and form can reflect or break these patterns. Lee has recently completed a PhD at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne and has also studied postgraduate education and urban planning. She is a lecturer in Creative Arts and Expanded Performance at Deakin University.