William Dendinger III

Abstract

The Catholic Church has held a contentious relationship with the LGBTIQ2+ community. The complicated history between the two groups and current viewpoints of the Church elicit questions on equality and the reasoning behind anti-LGBTIQ2+ rhetoric from the Vatican, such denouncing same-sex marriages. By analyzing queer space and narratives detailing conflict between the Church and Chicago’s LGBTIQ2+ community in the 1980s, this essay questions Catholic viewpoints and the boundaries of sacred space. The conceptual design for the Cappella of Queerness serves as an architectural loophole to current same-sex marriage issues and memorializes clergy members who stood with the LGBTIQ2+ community to fight for equal rights against powerful figures within Chicago’s city government and the Church itself. Through this design exploration, the concept of queer space is revealed as an action of creating and appropriating space rather than a set building typology. The intersection between what makes queer space and sacred space share in the ideas of social narratives created by occupants who activate these places.

Queerness in Catholicism

‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ Matthew 7:12 (ASV). This simple, yet difficult principle to live by found in the Bible is known as the Golden Rule. Those familiar with Christianity may know it as ‘love thy neighbor as thyself’ or ‘treat others as you would like to be treated.’ Simply put, this scriptural statement says we should love and treat each other with the respect and dignity we want for ourselves. If you grew up Catholic, like me, you might remember hearing this preached to you as a child constantly. You may even remember sitting through seemingly endless homilies as a priest droned on about the need to love others and follow the principles outlined in scripture. During Mass, Catholics turn to each other and say ‘Peace be with you, and also with your spirit.’ At the end of Mass, a priest finally concludes the ritual by announcing ‘The Mass is ended. Go in peace.’ These repetitive statements become so engrained into the psyche of Catholics, that at a certain point it is almost second nature as the congregation mindlessly mumbles these phrases in a cult-like trance. How does the Catholic Church live out these statements though? The next week a priest’s homily may be on the topic of homosexuality in the eyes of the Catholic Church, which may take on a much darker tone.

The Catholic Church and the LGBTIQ2+ community have always seemed to be at odds with one another. Homosexuality is viewed as a sin and the Vatican has recently reaffirmed the Church’s stance on same-sex marriage. In March of 2021, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which is responsible for defending Catholic doctrine, released a message when questioned on the Church’s stance on gay marriage that stated the Church cannot bless same-sex unions. This message was then approved by Pope Francis. A portion of the statement reads, ‘Rather, it declares illicit any form of blessing that tends to acknowledge their unions as such. In this case, in fact, the blessing would manifest not the intention to entrust such individual persons to the protection and help of God, in the sense mentioned above, but to approve and encourage a choice and way of life that cannot be recognized as objectively ordered to the revealed plans of God.’[1]

The dichotomy of preaching love for others, yet denying the love of others is odd and somewhat hypocritical. How do we treat others as we want to be treated, yet deny them equality? Is there a loophole in fine print to the Golden Rule that I missed in all my years of Catholic schooling?

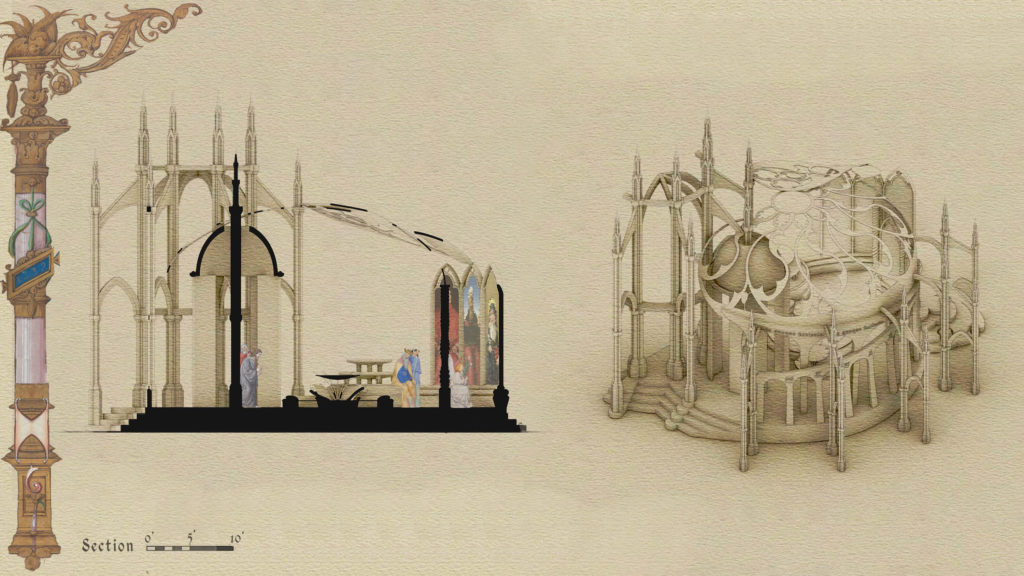

‘Camp’ Methodology

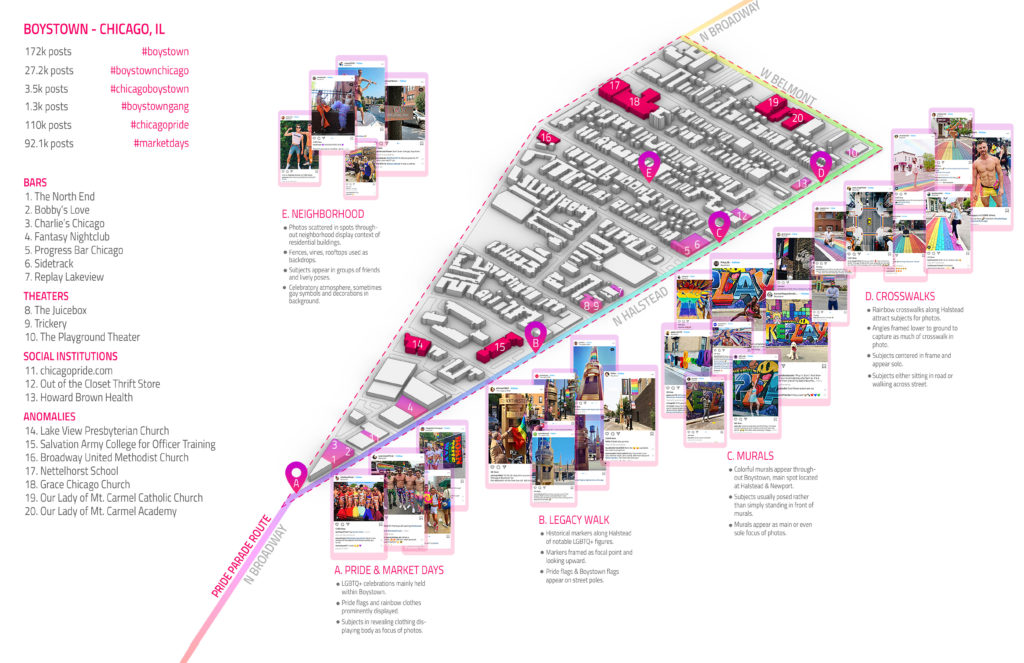

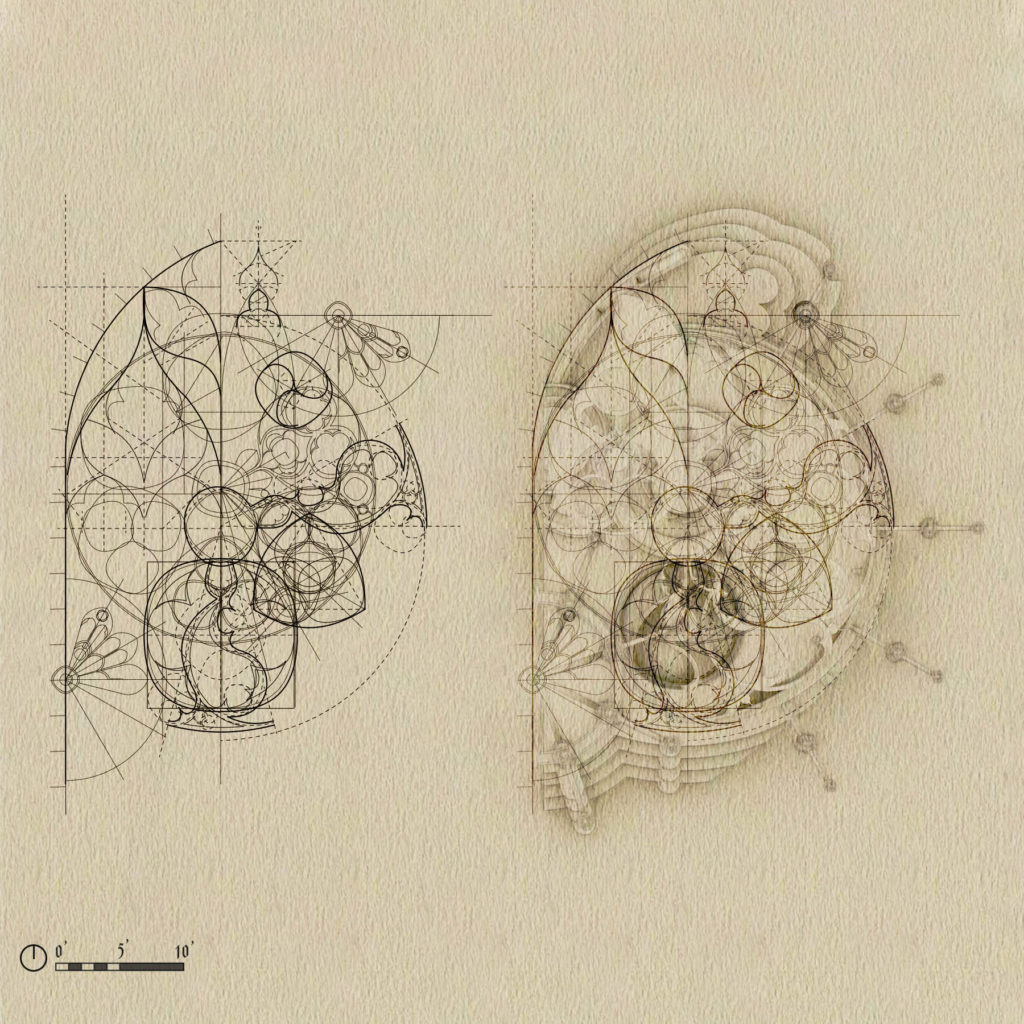

Figure 1

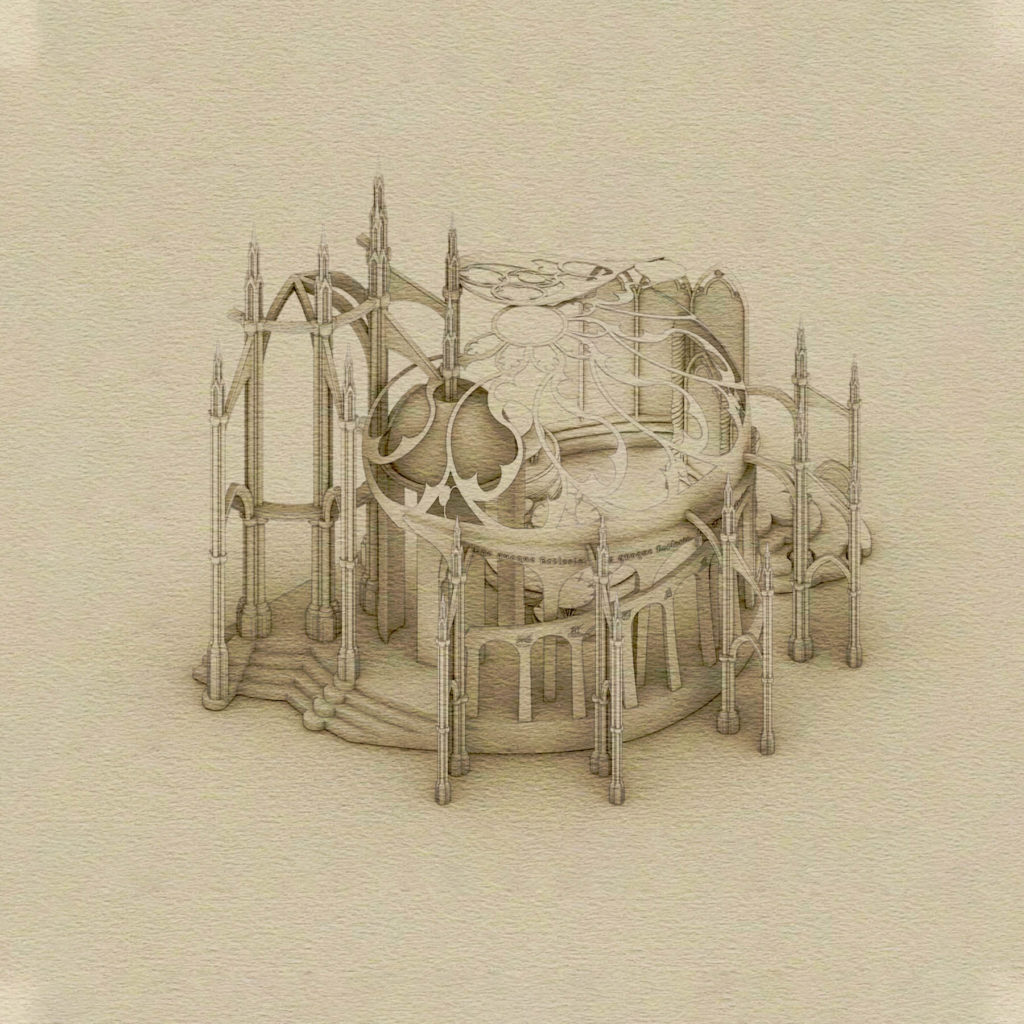

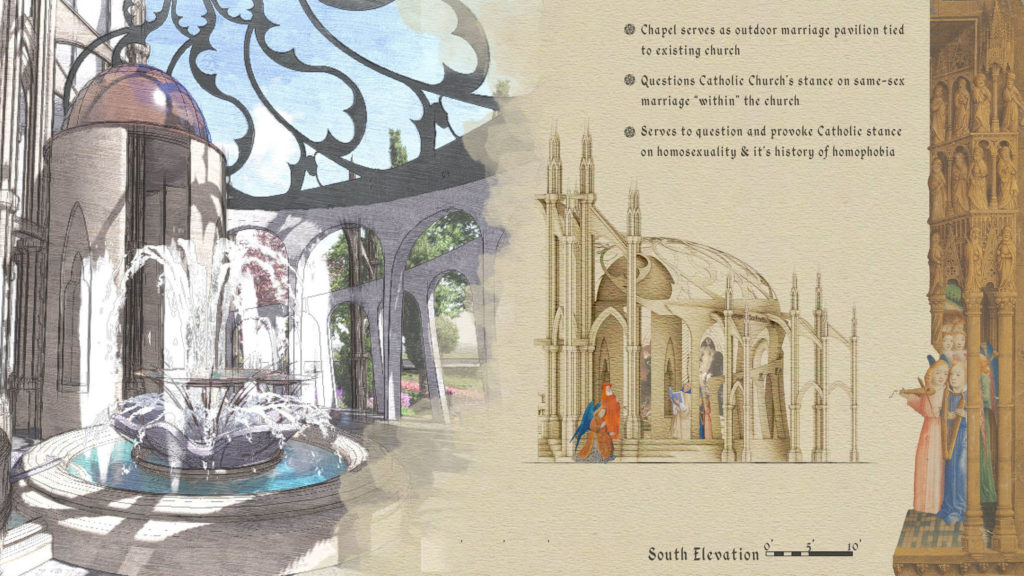

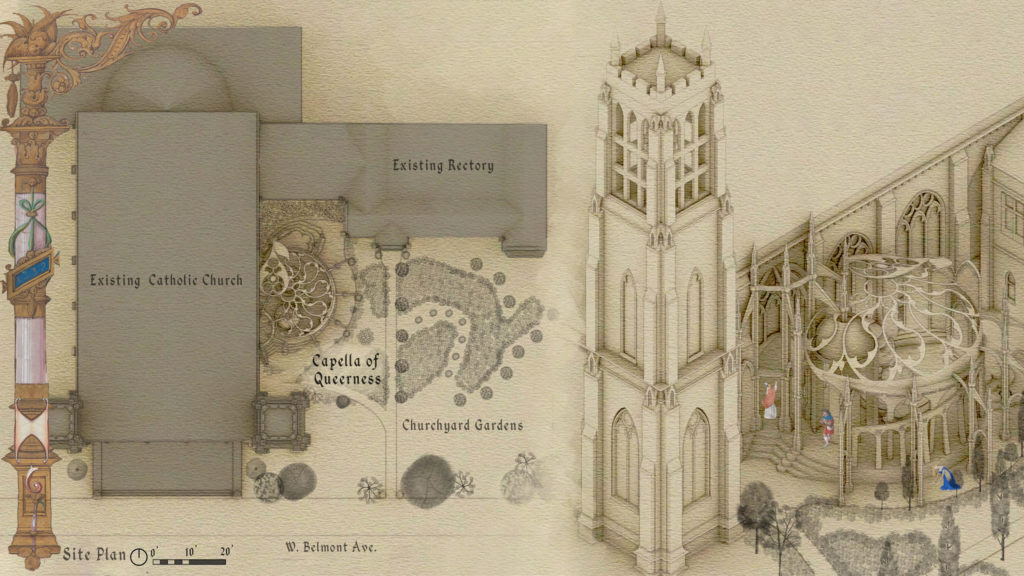

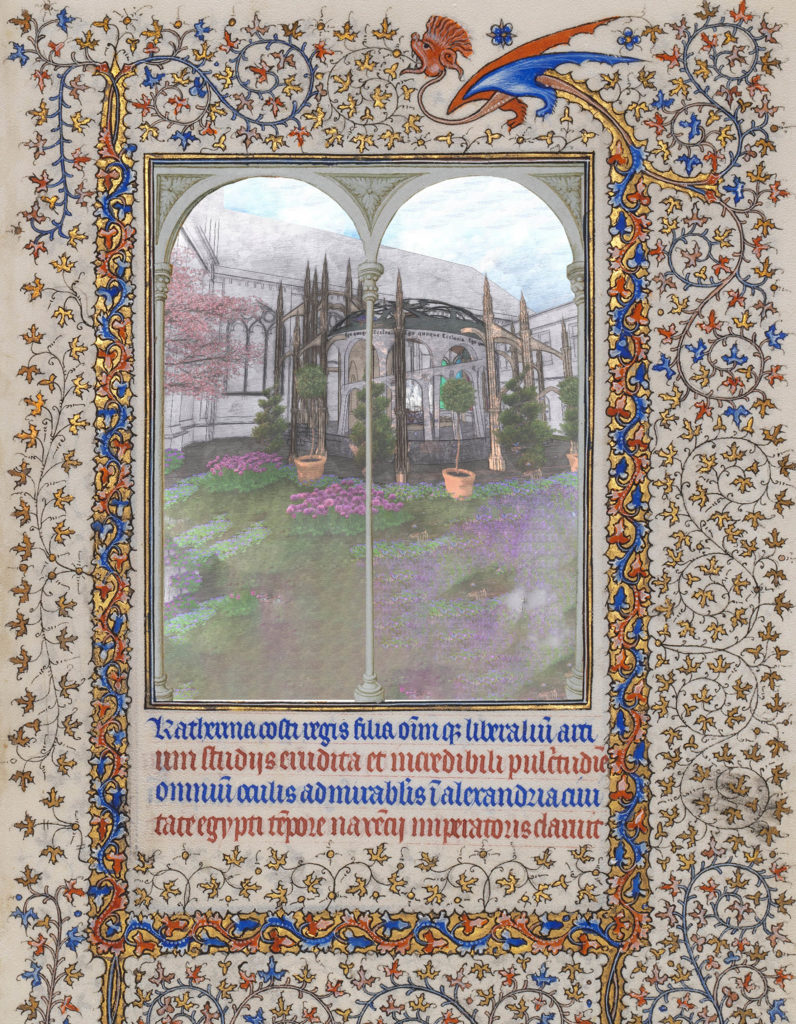

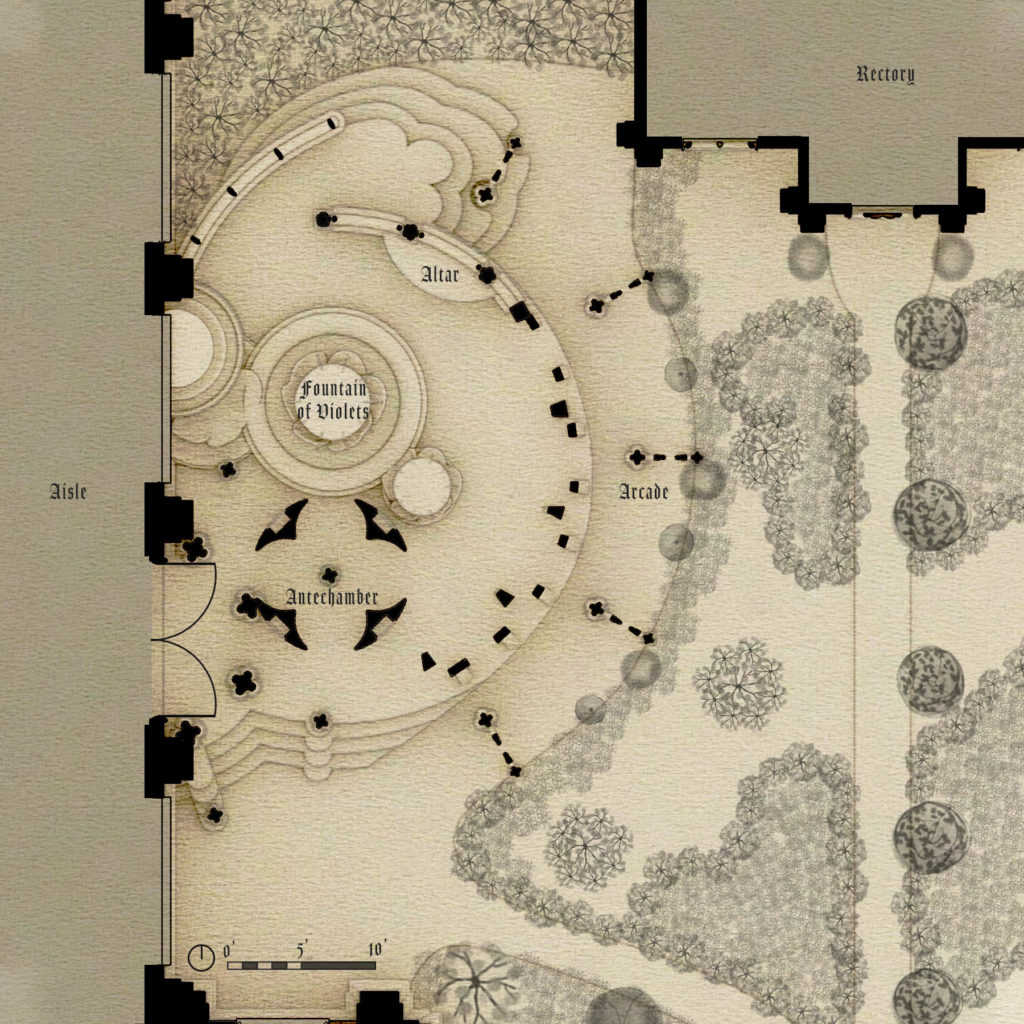

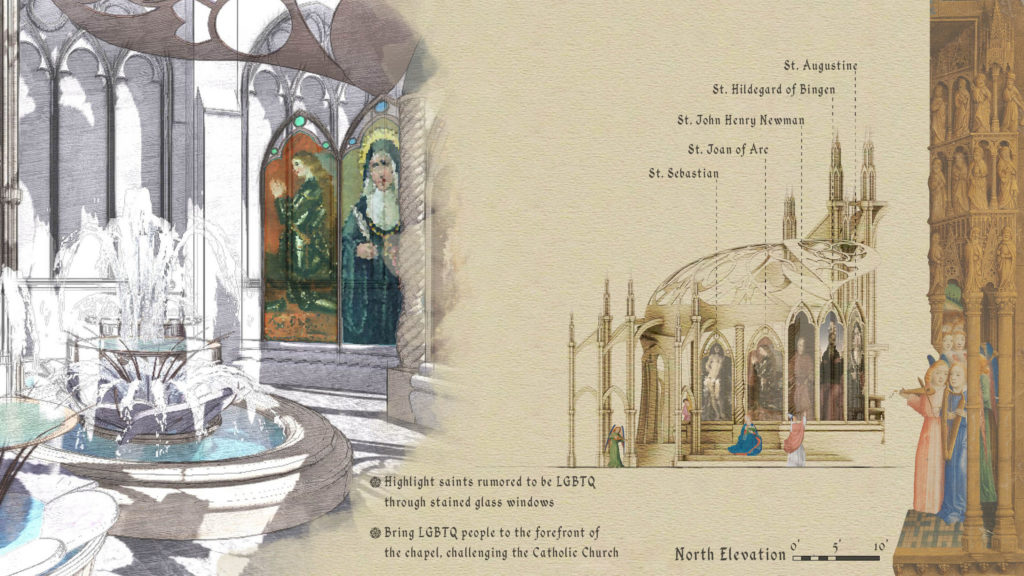

The contradictory ideological stance and homophobic rhetoric of the Catholic Church brings up many questions and challenges. In this essay, I explore queer space in architecture to understand its relationship between LGBTIQ2+ social narratives and their impact on spatial conditions. This is approached through the study of Chicago’s built environment and its LGBTIQ2+ community. Through multiple interviews with Chicago LGBTIQ2+ community leaders, readings of queer architectural theorists like Andrés Jaque, Christopher Reed, and Aaron Betsky, and finally mapping physical LGBTQI2+ sites versus social media tag locations in Chicago, Figure 1, we can analyze their conjunction to see queer spaces as atmospheres defined by the stories enmeshed within such spaces. Furthering this research methodology into a design process of queer space, we must draw upon even more wildly confusing sensibilities through the exaggerated and avant-garde lens of ‘camp.’ Rather than a particular style, ‘camp’ is a sensibility that is “something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing; a style or mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated and often fuses elements of high and popular culture,”[2] as defined by Merriam-Webster. Susan Sontag provides an essential guide to exploring the idea of ‘camp’ and the queerness of it in her essay ‘Notes on Camp.’ Camp is a confusing landscape of “theatricality, aestheticism, artificiality, exaggeration, incongruity, humor, parody, and twisted irony”[3] which has “proved a vital resource for theories of eccentricity, social stigma, leisure, unorthodox sexuality, and subversion of gender identity.”[4] There is no one specific way to pinpoint what is Camp. Camp allows for a multiplicity of contradicting ideas to exist in the same realm at once. Sontag explains that Camp isn’t strictly gay, but does explain “homosexuals, by and large, constitute the vanguard and the most articulate audience of Camp.”[5] She draws a connection to gender/sexuality as “prone to Camp sensibilities because its style is strongly exaggerated.”[6] Her theory is that queer culture legitimizes itself through Camp by “promoting form over content, or aesthetics over morals” and it is about playfulness rather than condemnation, dissolving the outrage of moralists against gay culture.[7] Through this lens, my design exploration sprinkles queerness into a space, Figure 2, that historically has been unwelcoming to LGBTIQ2+ people to create vibrant moments that evoke glimmers of connection to the stories of figures and events that have often been overlooked or erased. This essay illustrates the design and theory behind the Cappella of Queerness, Figures 3 and 4. According to first-hand account from longtime activist and gay bar owner, Arthur Johnston, the Catholic Church played a major role in the fight for LGBTIQ2+ in Chicago during the 1980s. My design exploration led to the creation of a religious monument derived from the stories of those involved. The conceptual design for this open-air chapel acts as both a historical record of local LGBTIQ2+ and Catholic history, but also a provocation to the Church. It serves to keep fighting for LGBTIQ2+ rights within the eyes of the Catholic Church. Through a ‘camp’ lens, the design of this chapel highlights the stylization and artifice seen in Catholic architecture, but appropriates them into a queered space. In doing so, the sanctity of a religious space combined with its queerness create an atmosphere which questions the boundaries of what really is holy ground. It appropriates Catholic architecture and as Christopher Reed says “fundamentally, queer space is space in the process of, literally taking place, of claiming territory.”[8] This project is not meant to be thought of as a fully constructable architectural design. Rather, it is meant to provoke conversation, stand in silent solidarity with those it remembers, and voice one facet of the continuing fight for queer people today.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

The Catholic Problem in Chicago

As previously stated, my essay explores the LGBTIQ2+ community within Chicago and how religion has played an important, yet controversial role in the recent history of LGBTIQ2+ rights, specifically in the 1980s. The Catholic Church had an abundance of political infighting on the topic at this time, which was only exacerbated by the horrors of the AIDS crisis occurring simultaneously. Many bishops and archbishops at this time began banning pro-gay Catholic organizations such as DignityUSA and New Ways Ministry from their churches or wrote to other bishops and communities asking them not to support these ministries as Archbishop James Hickey of Washington D.C. did in 1981.[9] According to Michael O’Loughlin, the Vatican even went so far as to release a letter in 1986, “when 25,000 Americans had already died from AIDS-related complications, saying that homosexuality itself was sort of a defect.”[10] New York’s Archbishop, Cardinal O’Connor, at the time fought to stop the distribution of condoms, calling them a sin. As Lulu Garcia-Navarro points out, “critics of the church’s policy say millions were needlessly infected.”[11] However, at this same time some Catholic priests and nuns took a stance against the bishops and cardinals to support LGBTIQ2+ people. Jesuit priest, Fr. John McNeill issued a press release in 1986 that he could not in good conscience obey an order to give up on ministering to gay people.[12] Meanwhile in New York, as Cardinal O’Connor continued his institutionalized attack against queer people, the Sisters of Charity took care of AIDS patients at St. Vincent’s hospital.[13]

To understand the context and memorial aspect behind the Cappella of Queerness, we must first understand the fight for equal rights in Chicago and the advocacy of Catholic nuns. Arthur Johnston, owner of Chicago’s largest gay bar, Sidetrack, and long-time LGBTIQ2+ activist, was involved in helping to pass legislation for LGBTIQ2+ rights in Chicago and recalled the emotional, arduous journey. In 1979, alderman Cliff Kelley introduced legislation to Chicago’s city government questioning whether or not it was lawful to fire people based on sexual orientation. As Arthur Johnston explained, ‘In other words, should it be okay to use sexual orientation to deny people an apartment, a job, public accommodations, or access to credit transactions?’[14] Legislation like this had never been brought to a committee vote or a vote of any kind until July of 1986. Chicago’s city government at the time relied on aldermen, or representatives from each ward throughout the city, to vote on issues and pass legislation. The LGBTIQ2+ community finally had this specific issue brought to a vote in 1986 after years of rallies, campaigning, and fighting for a chance at equal rights. During the meeting, the leader of the side supporting the LGBTIQ2+ community was Bernie Hansen. He was a newly elected alderman for the 44th ward. ‘We were leaning forward in our chairs, trying to hear as the aldermen debated our lives.’ Johnston explains that as the debate went on, Hansen’s arguments fell flat and the other city aldermen thought that most, if not all, of the city’s LGBTIQ2+ population, lived in Hansen’s ward, the area between Halsted Street and Lake Michigan. Today, the area is cleverly known as Boystown. After the lackluster debate, the final vote count was taken. The ‘yes’ votes tallied eighteen, ‘no’ votes tallied thirty, and ‘not voting’ were two. Chicago’s city government had just deemed it legal to discriminate against gay people. Johnston called this ‘an extra slap in the face.’[15]

As he and many other disheartened LGBTIQ2+ people shuffled out of city hall, alderwoman Kathy Osterman, the representative for the 40th ward, pulled Johnston into her office to immediately begin analyzing the vote. After some thought and frustration, they began to realize a pattern emerging. There was a ‘Catholic problem.’ They found that out of the eighteen ‘yes’ votes, there were eleven Protestants, one Jewish person, four people of indeterminant religion, and two Roman Catholics. On the other hand, of the thirty ‘no’ votes, twenty-eight were Catholics. Later, Johnston and Osterman discovered that the night before the vote, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin made a call to one of the most influential and religious leaders in the city government, Ed Burke. Cardinal Bernardin asked Burke to make sure that the vote failed. For those unfamiliar with the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, cardinals are senior members of the Church that serve for life. They are second in precedence only to the Pope, who handpicks them, and they outrank archbishops and bishops who they appoint. Bernardin was appointed to the rank of Cardinal in 1983 and held conservative, homophobic views. Fearing retribution from both Cardinal Bernardin and Ed Burke, two very powerful figures in Chicago at the time, the other devout Catholic aldermen fell in line with the vote. How do you move forward? What do you do? ‘And then came the nuns.’[16]

Then Came the Nuns

Osterman and Johnston came up with a plan to use Catholicism against itself. At this time, many of the nuns that led the Civil Rights Movement in the South were living in Chicago. As Art explained, most of the notable marches in the Movement were led by nuns because there were fewer chances of firehoses and dogs being used on them and they were always willing to go first. So, they reached out to the nuns of the Chicago Catholic Women and asked for their help to fight against their own Church. Johnston called these women, ‘crazy, wonderful radicals’ that were willing and able to help the LGBTIQ2+ community. One of the first steps in their plan was to have nuns regularly attend city council hearings as gays and lesbians constantly brought issues of equal rights to hearings and votes. The leader of these nuns, Sister Donna Quinn, worked with alderwoman Osterman to sway the other Catholic aldermen into voting for their cause. Their main tactic for this was to find the nuns that had taught the aldermen when they were children, find nuns that taught their children, or find any connection they could. Osterman would then bring the other alderman into a meeting room one at a time where these nuns would be waiting for them. Slowly, as the nuns began to convince the Catholic representatives, the votes for the LGBTIQ2+LGBTIQ2+ community began to grow with each successive hearing. Finally, after years of being denied and told that the LGBTIQ2+ community would never pass this type of legislation, on December 21st, 1989 the vote passed with twenty-seven ‘yes’ votes. It was no longer legal to discriminate against people based on sexual orientation in Chicago thanks to an unlikely ally. The humble nuns defied powerful forces in the Church and government. When faced with questions opposition from aldermen followed Cardinal Bernardin’s stance, the nuns would simply say ‘I’m the Church too.’[17] Their humble statement proved that the Catholic Church could accept LGBTIQ2+ individuals and show them love.

Provoking the Church

While the radical nuns of the Chicago Catholic Women fought hard in the 1980s to advance LGBTQ rights, the Catholic Church retains many homophobic views on queer people. As previously stated, the Church still does not allow same-sex marriage within the Church. The announcement from the Vatican that this archaic rule has been upheld, with very little basis one might argue, is disheartening for a vast number of LGBTIQ2+ Catholics including myself. After being raised in a religious family and attending Catholic schools for a majority of my life, but then being told that I and millions of people like me are not seen as equal in the eyes of the Church, and therefore in the eyes of God, shakes my belief in the Church. Do we not profess that everyone is created equal under God? Or to love one another as God loves us? How does the Church contradict itself in these statements? These conflicting examples of official Church views and clergy members are what led to the design exploration of the Cappella of Queerness. The Cappella twists and plays with Catholicism’s symbolism, forms, and views in an architectural manner that pokes at the Church, begging to provoke it.

Figure 5

The first provocation comes with the site selection, as a subtle slight to Cardinal Joseph Bernardin’s legacy. The proposed site for the Cappella of Queerness is on the grounds of Our Lady of Mt. Caramel church. This specific church was selected for two reasons. Cardinal Bernardin is buried at Our Lady of Mt. Caramel Cemetery in Chicago. One can only imagine his anger if an LGBTQ monument were to be built onto the church sharing the namesake of his final resting place. Second, the church sits in an odd location within Chicago. It is located in the middle of the neighborhood of Northalsted, more popularly known as Boystown. This ‘gayborhood,’ as many call it, is home to one of the largest LGBTIQ2+ communities in the U.S. In 1998, Chicago was the first city to officially establish a ‘gay village.’ The area is now an extremely desirable place to live with rising rent prices, rainbow crosswalks, pylons lining the street commemorating queer historical figures, numerous gay bars and stores, and an uncountable amount of pride flags and other iconographies. Interestingly, the name ‘Boystown’ was a tongue-in-cheek naming scheme based on the Catholic Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska founded by Father Flanigan in 1917 as a home for troubled youth.[18] Our Lady of Mt. Caramel’s church was built well before Boystown was recognized as a ‘gayborhood,’ but there is something to be said for the clear pattern of LGBTQ people having the last word in these symbolic gestures. The current church was built in 1913 in English Tudor Gothic style.[19] Later, a school and rectory were added to the site. The buildings of Our Lady of Mt. Caramel are beautifully crafted out of limestone with intricate details and tracery. The church presents itself as an imposing figure to the neighborhood as it dominates the surrounding buildings with its tall belltowers, large doors, and beautiful stained glass windows. The rectory connected to the church sits back from the street, allowing the east end of the property to open up with a large green space. The Cappella of Queerness would be attached to the east face of the church in the middle of the churchyard with the rectory situated to the north as shown in the site plan of Figure 5. The first design move of this chapel examines the existing Gothic motifs of the church. The chapel should look as if it is part of the physical church, and therefore fit in with its site and Catholic religion. Subtly, it begins to queer the elements and ideas of the physical church and the religious traditions. Figure 6 shows how the chapel derives its plan from a process of overlaying and tracing multiple gothic motifs from stained glass windows and traceries. From this, exercise multiple zones and forms began to take shape. One can see the abstraction of various rose window tracings into the domes of the chapel. The stairs curve to meet the angle of a pointed arch while the buttresses and arcade follow the geometry outlined in the floor plan. Finally, other elements such as the altar, fountains, and antechamber take shape from the overlapping collisions of traceries to form oddly shaped programs. Through this technique, I sample from historical sacred geometry and begin the process of queering it to form the Cappella. Every detail of this chapel takes cues from Gothic architecture, Catholic symbolism, the existing church, or even the chapel itself. They are then stretched, rotated, compressed, and turned on their heads to reshape Catholic architecture. In doing this, the chapel draws its design directly from Catholicism but highlights its ideological schism in its approach to the new design.

Figure 6

The outdoor chapel serves as a dual function to highlight the contradictory relationships of the LGBTQ community and clergy. First, it serves as a memorial to the nuns of the Chicago Catholic Women. Symbolism and storytelling are important features in many churches, so the historical story of their advocacy for the LGBTIQ2+ community and Cardinal Bernardin’s opposition are inscribed along the west archways which can be viewed as one walks through around the arcade. The nuns’ simple, but resounding statement ‘I’m the Church too’ is also inscribed in the arches and repeated symbolizing the millions of LGBTIQ2+ Catholics who are also the Church shown in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7

![]()

Figure 8

The Marriage Loophole

The second function of the Cappella serves as a type of loophole to Catholic doctrine. While gay marriage is not allowed within Catholic churches, it could however exist in proximity to them. The chapel has many of the elements of a church such as an altar, baptismal font, stained glass windows, antechamber, reference Figure 9, and similar architectural language of Our Lady of Mt. Caramel. The schism from the church occurs when this outdoor space, which is accessible to anyone, is transformed into a wedding ceremony between two people of the same gender identity. The chapel connects through the east façade of the church. As users cross through this threshold from church to chapel, are they still considered sacred ground? The boundary between physical space and ideological virtues is stretched thin and brought into question by the mere proximity of sacred spaces. The parasitic attachment of the Cappella onto the side of the church acts to provoke Catholicism.

Figure 9

Imagine a heterosexual wedding occurring inside the church that is seen as worthy of ecclesial blessing. Simultaneously, a homosexual wedding could be occurring in the Cappella with the same love shared between two people on display before witnesses present and God. Just mere feet apart with many of the ceremonial rituals and emotions, these two ceremonies could exist while one is deemed worthy and loving, and the other is seen as illicit or sinful. The chapel pushes same-sex marriage right in front of the church’s doors. This act serves to push the Catholic Church’s boundaries and protest long-held homophobic rhetoric. In Pope Francis’s own words, ‘If someone is gay and is searching for the Lord and has goodwill, then who am I to judge him?’[20]

Religious Iconography

The Cappella imitates Catholic churches through its heavy use of symbolism in its architectural language. However, unlike the symbolism of Gothic church construction, the Cappella’s symbolism highlights and praises queerness. Upon first glance, one might think that the stained glass windows lining the north elevation of the chapel are nothing more than typical portrayals of saints such as Sebastian, Hildegard of Bingen, Augustine, John Henry Newman, and Joan of Arc shown in Figure 10. However, the saints depicted in these windows are all rumored to have been LGBTIQ2+.[21] These are not the only saints to have their sexuality or gender identity questioned. This topic is also not readily known to most people, or even discussed by the Catholic Church. However, by showing saints who may have been gay, lesbian, or transgender the chapel shows that sexuality and gender identity do not determine the sanctity of one’s soul. The baptismal font, or Fountain of Violets, references the association of Sapphic Violets with the LGBTIQ2+ community, specifically lesbianism. According to Sarah Prager, this association dates back to the Greek poet, Sappho (630-570 BCE), who lived on the island of Lesbos, and her prominence and sexuality is where the lowercase-L lesbian come from. In her poems, she mentions the color violet and purple blooms many times, which might be where this color first was associated with queerness.[22] Throughout history violet, and lavender specifically, have symbolized queerness and in 1969 it came to symbolize LGBTIQ2+ empowerment through sashes and armbands for a ‘gay power’ march to commemorate the Stonewall riots. It also was used as a protest of unfair treatment of lesbians in the National Organization for Women, whose leader called lesbianism the ‘lavender menace.’ In protest of this, activists wore purple to bring up conversations about lesbianism.[23] Violet also has a symbolic standing within the Catholic Church during two very sacred periods in the Catholic calendar. During the times of Lent and Advent, the periods before Easter and Christmas, purple is used throughout churches and clergy vestments to show reverence and waiting for two of the most sacred holidays in Christianity. Again, the Cappella’s symbolism is not blatantly obvious, unless one pieces together the history and iconography present. The Cappella appears as a normative piece of religious architecture, falling in line with Catholic doctrine. In actuality, it takes Catholic icons and flips them into queer icons.

Figure 10

Even the Gothic architectural elements and structure of the chapel play with this notion. As the chapel mimics the buttresses, tracery, steps, domes, and spiral columns of religious architecture, it distorts them subtly shown in Figure 11. These distortions, such as the layering of domes within domes, the oversized font, or even steps morphing around and repeating a column’s landing act as playful interpretations of sacred designs. It queers the architecture and iconography just enough that a meditative visitor might begin to notice the small peculiarities or pick up on the mannerisms of this space and begin questioning it. On the other hand, a devout user may not notice the interpretations and blindly accept this architecture in the same way they accept outdated views of Catholicism.

Figure 11

Queering Religious Architecture

In designing this chapel, I sampled architectural elements of Gothic churches, religious iconography, and Catholic rituals to then re-appropriate them into a queer space. This important mimicry and twisting of Catholic architectural elements were equally important in the representation of the chapel. The design was created using 3D modeling software to accurately model gothic elements from various images and sketches then wildly distort them. Each of the architectural drawings appears as a hand-drawn plan, elevation, or section to the untrained viewer. In reality, these hand-drawn looks were a simple manipulation in the modeling software combined with Photoshop work. The text and decorative borders around certain images were sampled from illuminated manuscripts using Photoshop. Finally, the last step in this technique was to use scale figures Photoshopped from the same illuminated manuscripts or other religious artworks. The figures are medieval depictions of saints, clergy, and angels as a final way of faking the holiness of this design. By depicting this work as an aged Gothic design, as if found in an illuminated manuscript, it conveys that the LGBTIQ2+ community has been entwined with religion throughout history. The Church may denounce and ignore the LGBTIQ2+ community, but it can no longer retain this stance.

While the Catholic Church and LGBTIQ2+ community condemn each other, the Cappella of Queerness offers a space for any user. It may not be officially blessed, and could be seen as sacrilegious by some, but the Cappella offers architectural elements, symbolism and narratives, forming an ephemeral sense which may be close enough to classify it as a holy space. What makes a space holy may be in the same realm of what makes a space queer. There is no clearly defined answer for either typology, yet it is something that we as occupants of space can simply feel and understand. The open-air chapel is readily accessible to the public. As one enters through the flower gardens of the churchyard, they encounter the highly ornamented structure clinging to the side of its imposing host. The light limestone and marble of the chapel glisten in the daylight and create a sense of age within the structure as if it has always been a part of the history of the church. Climbing the playfully shaped stairs and entering into the chapel’s antechamber, one might pause in this small, shaded enclave. From above, a ray of light pierces through the antechamber’s oculus. Stepping out into the main chapel, a symphony of fountains greets prayerful visitors while sunlight glistens off the intricate metalworking of the copper dome above. The white stone around the chapel comes to life as the stained glass windows fill the space with color. Finally, as one exits and walks along the gravel path through the arcade of buttresses, the symbols and Latin inscriptions of the nuns’ story wrap the arches. This tiny piece of stone, metal, and glass becomes a sacred space, not from the decree of clergymen, but from those who occupy it and the narratives shared within it.

Narratives of Queer Space

While the Cappella of Queerness serves as an architectural protest, condemning the Catholic Church’s views on gay marriage and its history of homophobic rhetoric, it brings into question the sanctity of physical space and religious rituals in proximity. By sampling religious forms and representations then appropriating them into queer space to question the Church, this small, yet thought-provoking design teeters playfully on heresy. This design also brings into question a much larger issue. What is the architectural concept of queer space and why is it important? As Evan Pavka suggests, “queer spaces are essentially acts of appropriation – a calculated repurposing of existing typologies of building, claiming of space whether visible or invisible. These structures become queer only in the sense that they are activated, inhabited and transformed by queer-identifying individuals.”[24] This question has no definite answer even though it has been explored by many architectural theorists such as Aaron Betsky, Christopher Reed, and Andrés Jaque Even though the Cappella of Queerness serves as a form of queer space, it alone cannot answer this question. Rather, it serves as a facet of this topic to open a dialogue and highlight a small set of LGBTIQ2+ issues through architecture.

What defines queer space? What defines hetero space? Queer architecture is not a set typology of building, “for there is no intrinsically queer house, dwelling, or building.”[25] Queering space is a process of performative acts and inhabiting space, rather than the by-product of surface treatments (rainbow iconography, LGBTIQ2+ symbols, etc) and programmatic elements (gender-neutral bathrooms).

Architectural space “is conceived of as existing in and through events; events that are themselves composite, complex, and plural” and the places we occupy have “spatial effects that resonate in human relations.”[26] Queer space is defined by the temporal, fleeting events, conversations, and sexual acts that take place within the defined boundaries of space, thus transforming the atmosphere of a bar, street, bathroom, park, or even whole neighborhoods.

“Queer space is the collective creation of queer people.”[27] The creation of such space “involves a potentially extraordinary variety of events” and creation of counter, queer, autonomous spaces in the “margins of dominant space for the proliferation of new pleasures, desires, subjectivities.”[28] This complexity of queerness and temporality in space does not simply imply gender and sexuality only exist when a space is occupied, but traces of these can be left behind marking queer space. On one hand, Aaron Betsky argues for the temporary “useless, amoral, and sensual space that lives only in and for experience” stating that “the goal of queer space is orgasm.” Christopher Reed, however, argues queer space is a more stable claim to space against the dominant heterosexual matrix, seen in gay bars, lesbian archives, student groups, sex toy stores, social services, political organizations.”[29]

In conclusion, queer space is directly influenced by the expression of gender and sexuality of the bodies that inhabit it. I argue that queer space is critical in shaping LGBTIQ2+ individuals’ and communities’ narratives by bringing their struggles, celebrations, and everyday moments of what it is to be queer to the center stage in the urban landscape. As these concepts develop into architectural interventions they become active agents in their own narratives. The Cappella of Queerness or other concepts of queer space are not meant to be built objects. Rather, each is intended to scratch the surface of a topic and provoke conversation, laughter, or anger. The architect plays a major role in these topics. As architects, it is our responsibility to use our works to argue for social and political justice. By shaping space, we define how it is occupied and how the narratives of users can play out, promoting equality and justice. The “gay ghetto” or “gayborhood” may no longer be needed and is disappearing, but spaces need to be designed taking into account the identities and safety of the LGBTIQ2+ community. In many countries, homosexuality is still illegal. Even in places we consider to be safe, LGBTIQ2+ people still have been abused physically, mentally, or through unjust institutions.

I am pushing the gay agenda, an agenda that demands equality and acceptance. One that shows that I am different, that I cannot forget this because it is what makes myself and so many other LGBTIQ2+ people unique. If we forget this, it becomes easy to strip us of everything generations before have fought for, and everything the generations after will continue fighting to preserve. Like glitter, queer spaces are sprinkled throughout the urban landscape and activate the sites they occupy. Architectural spaces such as the Cappella of Queerness may not be queer without the collective of LGBTIQ2+ individuals occupying them or their backgrounds being readily known. Still, they serve to draw people to them, stand in silent solidarity with them, or actively disrupt them.

[1] Bill Chappell, “Vatican Says Catholic Church Cannot Bless Same-Sex Marriages,” NPR, March 15, 2021.

[2] Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. “camp,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/camp

[3] Andrew Bolton, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019)

[4] Andrew Bolton, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019)

[5] Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” 1964.

[6] Johanna King-Slutzky, “camp,” The Chicago School of Media Theory (blog) (University of Chicago, 2010)

[7] Johanna King-Slutzky, “camp,” The Chicago School of Media Theory (blog) (University of Chicago, 2010)

[8] Christopher Reed, “Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment,” Art Journal 55, no. (1996): p.64

[9] Kristen Hannum and Elizabeth Lefebvre, “The Relationship Between LGBTQ Catholics and the Church,” U.S. Catholic, April 2018.

[10] Lulu Garcia-Navarro and Michael O’Loughlin, “How the Catholic Church Aided Both the Sick and the Sickness as HIV Spread,” NPR, December 1, 2019.

[11] Lulu Garcia-Navarro and Michael O’Loughlin, “How the Catholic Church Aided Both the Sick and the Sickness as HIV Spread,” NPR, December 1, 2019.

[12] Kristen Hannum and Elizabeth Lefebvre, “The Relationship Between LGBTQ Catholics and the Church,” U.S. Catholic, April 2018.

[13] Lulu Garcia-Navarro and Michael O’Loughlin, “How the Catholic Church Aided Both the Sick and the Sickness as HIV Spread,” NPR, December 1, 2019.

[14] Arthur Johnston, “On The Mic: Outspoken LGBTQ Storytelling,” accessed September 15, 2020.

[15] Arthur Johnston, “On The Mic: Outspoken LGBTQ Storytelling,” accessed September 15, 2020.

[16] Arthur Johnston “On The Mic: Outspoken LGBTQ Storytelling,” accessed September 15, 2020.

[17] Arthur Johnston “On The Mic: Outspoken LGBTQ Storytelling,” accessed September 15, 2020.

[18] William Dendinger, Arthur Johnston, and Bradley Balof, “Interview with Art Johnston and Brad Balof – Sidetrack,” Octorber 30, 2020.

[19] “Parish History,” Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, October 9, 2017.

[20] “Pope Francis: Who Am I to Judge Gay People?,” BBC News, July 29, 2013.

[21] Taylor Henderson, “30 LGBT SAINTS,” The Advocate, June 2, 2017.

[22] Sarah Prager, “Four Flowering Plants That Have Been Decidely Queered,” JSTOR, January 29, 2020.

[23] Christobel Hastings, “How Lavender Became a Symbol of LGBTQ Resistance,” CNN, June 4, 2020.

[24] Evan Pavka, “What Do We Mean By Queer Space?,” Azure, June 29, 2020, https://www.azuremagazine.com/article/what-do-we-mean-by-queer-space/.

[25] Julius Gavroche, “Struggles for Space: Architecture Without Architects-Another Anarchist Approach (3),” September 28, 2017

[26] Julius Gavroche, “Struggles for Space: Architecture Without Architects-Another Anarchist Approach (3),” September 28, 2017

[27] Christopher Reed, “Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment,” Art Journal 55, no. (1996): p.64

[28] Julius Gavroche, “Struggles for Space: Architecture Without Architects-Another Anarchist Approach (3),” September 28, 2017

[29] Julius Gavroche, “Struggles for Space: Architecture Without Architects-Another Anarchist Approach (3),” September 28, 2017

Bibliography

Chappell, Bill. “Vatican Says Catholic Church Cannot Bless Same-Sex Marriages.” NPR. NPR, March 15, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/15/977415222/illicit-for-catholic-church-to-bless-same-sex-marriages-vatican-says.

Garcia-Navarro, Lulu and Michael O’Loughlin. “How the Catholic Church Aided Both the Sick and the Sickness as HIV Spread. NPR. NPR, December 1, 2019. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/783932572

Gavroche, Julius. (2017, September 28). Struggles for space: Architecture Without Architects-Another Anarchist Approach (3). Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://autonomies.org/2016/10/struggles-for-space-architecture-without-architects-another-anarchist-approach-3/

Hastings, Christobel. “How Lavendar Became a Symbol of LGBTQ Resistance.” CNN. Cable News Network, June 4, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/lgbtq-lavender-symbolism-pride/index.html.

Hannum, Kristen, and Elizabeth Lefebvre. “The Relationship Between LGBTQ Catholics and the Church.” U.S. Catholic Vol. 77, no. 3, April 2018. https://uscatholic.org/articles/201804/pride-and-prejudice-a-history-of-the-relationship-between-gay-and-lesbian-catholics-and-their-church/#

Henderson, Taylor. “30 LGBT SAINTS.” The Advocate, June 2, 2017. https://www.advocate.com/religion/2017/6/02/30-lgbt-saints#media-gallery-media-2.

Jaque, Andrés. “Grindr Archiurbanism.” Log, no. 41, 2017, pp. 74–84., www.jstor.org.libproxy.unl.edu/stable/26323720. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020

“On The Mic: Outspoken LGBTQ Storytelling .” Episode. Spotifyno. Love, Activism, & Whitney Houston. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4Z7ecVo6Ph0dj14losvZod.

“Parish History.” Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, October 9, 2017. https://ourlmc.org/parish-history/.

Pavka, Evan. “What Do We Mean By Queer Space?” Azure, June 29, 2020. https://www.azuremagazine.com/article/what-do-we-mean-by-queer-space/.

“Pope Francis: Who Am I to Judge Gay People?” BBC News. BBC, July 29, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-23489702.

Prager, Sarah. “Four Flowering Plants That Have Been Decidely Queered.” JSTOR, January 29, 2020.

Reed, C. (1996). Imminent Domain: Queer Space in the Built Environment. Art Journal, 55(4), 64. doi:10.2307/777657

“Responsum Della Congregazione per La Dottrina Della Fede Ad Un Dubium circa La Benedizione Delle Unioni Di Persone Dello Stesso Sesso, 15.03.2021.” Holy See Press Office. Vatican, March 15, 2021. Roman Catholic Church. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2021/03/15/0157/00330.html#ing.

Will Dendinger is an architectural designer currently based in Omaha, NE. He recently graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln with a master’s in architecture and minor in product design. His graduate thesis, Glitter Urbanism – LGBTQ Narratives in Architecture, analyzed the concepts of queer space through sociocultural investigations into Chicago’s LGBTIQ2+ community and architectural design. His belief as a designer is that architecture must foster a sense of human connection by creating space from the narratives of those whom it represents. His work has been exhibited in the Roca London Gallery’s Designing Out, Joslyn Art Museum’s Pull Up a Chair, and UNL’s Krueger Gallery.