Nishant Shahani

“Why do people walk into the disciplinary regime of the state?”

–Gopal Guru, Humiliation: Claims and Context, 15.

While completing the writing of my book manuscript, Pink Revolutions in the Fall of 2018, the Supreme Court of India declared its own “revolutionary”[1] judgement around Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, reading down its criminalization of consensual sexual activity between adults, thus effectively decriminalizing homosexuality in the eyes of the law. Deepak Misra, Chief Justice of India’s Supreme Court succinctly suggested that the interpretation of Section 377 to criminalize same-sex sexual activity between consenting adults was “irrational, arbitrary, and indefensible.”[2] In this brief essay/afterword, I revisit some of the celebratory rhetoric in the immediate aftermath of legal triumph in light of the logics of triangulation between queer politics, nationalism, and globalization in a post-liberalization context of India.

To offer an afterword of this kind is partially a function of a book project’s generic conventions that require concluding thoughts, but in this instance, it also served to address, however inadequately, what arrived quite literally after the book’s word. What follows then is a replacement for an earlier draft of a conclusion that I eventually rejected and revised in favor of this current version. Initially, the motivation behind the newer revision was to account for a material present that superseded the book’s limits. But as I re-wrote, I recognized that this “cancelation” or what Gayatri Spivak calls “writing under erasure” became crucial both conceptually and formally to the broader scope of the book itself.[3]

The afterword thus becomes a belated commentary on the rest of the book’s “present” that happened prior to the landmark Supreme Court ruling. Of course, the afterword will ultimately and inevitably be received as an already occurred past at the moment of its future reception. Put more simply, I am trying to point to the afterword’s temporality as one that is axiomatically marked by a kind of delay in various senses of the term—straggling signifiers that can never quite keep up with always shifting signifieds. If we are to believe globalization’s story about itself, the world is moving forward with rapid levels of speed. If India lives up to its designation of what Adam Roberts calls the “superfast primetime ultimate nation,” its pink revolutionary futures are marked by augmented growth and hustled momentum.[4] Perhaps then, the recognition of delay and belatedness, of never quite being able to keep up, becomes one way to contravene triumphant narratives of accelerated growth that obscure those who are immobile and stuck in time, those who experience temporal lags in access, or who are denied the spoils of modernity due to state-sanctioned hierarchies.

It is only appropriate that the after word recognizes the belatedness that structures its very form. While the afterword attempts to offset the rest of the text’s inability to keep up with context through the vantage of a more “caught up” present, it will still be marked by an inevitable inadequacy. Temporal lag in which events take place at “primetime” breathtaking speed, are always exceeding and overtaking their “original” framings, highlighting an obsolescence that can still hopefully and paradoxically be relevant. In her preface to and translation of Of Grammatology, Gayatri Spivak references the notion of sous rature—a concept that Derrida mobilizes via Hiedegger to cross out words of a text while still foregrounding the act of cancelation, making legible the very act of illegibility. Writing about her attempt to translate sous rature, Spivak contends: “My predicament is an analogue for a certain philosophical exigency that drives Derrida to writing ‘sous rature,’ which I translate as ‘under erasure.’ This is to write a word, cross it out, and then print both word and delection.”[5] The relationship of words to meaning is one that is always already twice removed, the latter always exceeding the former. To put it in temporal terms, language is overtaken by the contingencies of the concept, and thus it is always delayed and belated (just like this afterword). Yet Spivak writes that sous rature is “inaccurate but necessary,” that “language is twisted and bent even as it guides us.”[6] Thus delay is constitutive of the very mechanisms through which meaning is apprehended.

There are several ways in which the above theorization of delay marks this afterword on Section 377 (beyond logics of methodology or the very form of “after” words). Section 377’s belated reading down is itself seen as deferred entry into the time of Indian modernity (“finally we’ve entered the 21st century”) in which archaic colonial era laws are significations of colonial hangovers and impediments to markers of sovereign postcoloniality.[7] For many activists, the decision’s triumph was experienced in pointedly temporal terms—a kind of “finally,” “about time,” and “at last.” While the decision was marked by perpetual delay, September 6, 2018 was the day of eventual arrival—the moment when pink revolutions were actualized. But the relief and joy marking this epistemic shift from anticipation to arrival can never quite detach itself from the logics of delay. If delay, returning to the above theorizations, is constitutive of language, then in what sense can some of the representations of triumph function as a kind of sous rature? How are the performances of jubilation at this revolutionary moment of delayed arrival both “necessary” and yet “inaccurate” at the same time? What specters of delay still haunt the moment of revolutionary arrival?

It is worth qualifying that Spivak’s understanding of “writing under erasure” cannot simply be conflated with a theorization of mechanisms that produce invisibility. While the words are crossed out, they are still written, even through their visible cancelation (hence my own framing of this afterword as a kind of necessary but inadequate re-writing through literal cancelation). Thus in critiquing responses after revolutionary legal judgements, I am not suggesting that these responses are either unwarranted or unnecessary. To use Spivak’s own words, my critique is not simply an “exposure of error.” Instead, it is “the critique of something that is extremely useful, something without which we cannot do anything.”[8] In critiquing this epistemic moment of pink revolutions, I am not pointing to the myopias of celebration or that these expressions of joy are overdetermined or ensconced in ideological naivety. By writing this afterword, I am asking instead about afterworlds—i.e. what is yet to come and what remains to be done after the reading down of Section 377. In considering the afterlives of legal victories, I am crossing out “words” not as acts of erasure, but as ways to understand how structures of unintelligibility might haunt the very moments of purported legibility. Or to put it differently, what is lost when we supposedly arrive?

One of the most iconic and poignant images that marked the revolutionary ruling was a much retweeted and widely published drawing by political cartoonist Mir Suhail (Fig. 1, see below). The drawing usefully captures a visual representation of “pink revolutions,” depicting an image of the Supreme Court of India with a beam of white light entering from one wing of the building’s structure. From the other end of the Supreme Court’s wing, the singular beam is then gloriously refracted and magnified as a bright rainbow light, signaling the achievement of radical transformation. The tricolored Indian flag stands in the center of the court’s dome, functioning almost as if it were the prism-like conduit for this magnificent transformation. The image, of course, is a play on the classic scientific illustration of light dispersion through triangulated optics in which white light gets dispersed and fractured into its component colors. The image thus encapsulates the logics of triangulation that are endemic to pink revolutions that I theorized in the introduction. Suhail’s image appropriately depicts the central wing of the Supreme Court building that was constructed on a 17-acre triangular plot of land—its very geography indexing the trilateral logics discussed throughout the book between queerness, nationalism, and globalization.

Fig. 1: Mihir Suhail

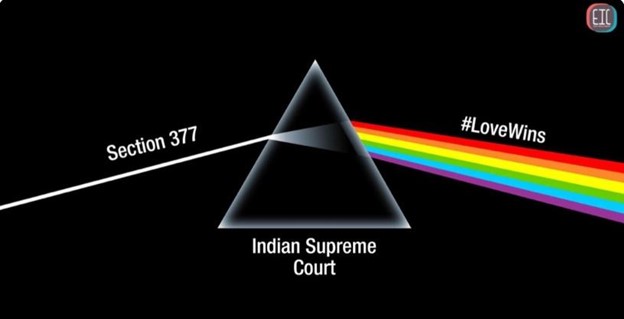

In a more literal version of Suhail’s drawing, the East India Comedy group similarly contributed its own celebration of the judgement, tweeting a diagram-like image of the prism in which the original white light represents Section 377, the triangle epitomizes the Supreme Court, and the refracted rainbow is marked with “#love wins” (Fig. 2). In this image, the celebration of legal institutions is not simply due to its production of sexual citizenship but in its engendering of intimacy in which the primacy (and privacy) of love overrides all else. The image thus achieves what Lauren Berlant has called a mode of “national sentimentality” that paradoxically has the effect of repudiating the political “on behalf of a private life protected from the harsh realities of power.”[9] The sentimentalizing of national culture is achieved, for example, in yet another image drawn by political cartoonist Manjul, who depicts the image of a lawyer with a copy of the Indian Constitution in front of him. The entire image is sketched in black and white with the exception of a conspicuous dash of rainbow color on the triangular shaped barrister’s band worn around the neck. The contrast in colors echoes the earlier depictions in which the triangles of revolutionary justice transform the mundane into the spectacular.

Fig. 2: East India Comedy

In this particular representation, the state is no longer a symbol of red tape or bureaucratic governmentality in which judicial inaction delays the achievement of justice or exacerbates the precarity of vulnerable populations—instead, it is humanized as the architect of a love that after protracted deferment, can finally speak its name. In various representations then, judicial signifiers get imbued with the afterglow of rainbow colored iridescence.

Fig 3: Suhail

For example, in another sketch by Suhail (Fig. 3), the multicolored scales of justice tilt to the left, foregrounding what Ashley Tellis and Sruti Bala call a “point of arrival” that marks state-centered queer activism in India, that is always illusory in scope despite the insistence on a politics of fulfillment.[10] Points of arrival that accompany epistemic moments of legal victory thus make a critical afterward/word even more imperative if the challenge to Section 377 is read through a more capacious lens of gender and sexual justice rather than the securing of consensual “gay” sex through the discourse of privacy rights. In this light, scholarship written prior to the “revolutionary” judgement is not redundant or antiquated—in fact, it assumes greater critical importance. For example, in an essay written just after the Delhi High Court decriminalization of Section 377 in 2009, Jyoti Puri reads rape law (Section 375) in conjunction with sodomy law in India in arguing for a more “genderqueer” lens that considers legal “victory” around 377 in light of feminist engagements with the law in India. Puri not only points to entwined histories of challenges to rape and sodomy laws in India—some of the earliest challenges to Section 377 appearing in the 1993 draft of rape law reform—she also points to the manner in which rape and sodomy laws “militate against…forms of violence but each in its own way also becomes sexual violence itself.”[11] For example, judicial framings of Section 375 enshrined the sanctity of marital “privacy” by exonerating the familial sphere from the occurrence of rape and sexual violence. As Puri remarks, “rape law is biased toward sexual violence that occurs outside the realm of the family and especially the marital relationship” (213). And it is precisely this realm of familial privacy that challenges the Supreme Court decriminalization re-centers in its victorious ruling.

In yet another political cartoon, Sorit Gupto depicts legal triumph by illustrating two men hand-in-hand, one of them holding his fingers aloft in a “V” for victory sign and the other carrying an enlarged judge’s gavel to which is attached a rainbow flag . The speech balloon above the image contains the words “Happy Delayed Independence,” at once metonymically linking the repurposed judge’s gavel (now a holder for the makeshift rainbow flag) to a pride that is both proudly nationalist and queer in scope.

While the Supreme Court’s enabling of “delayed independence” suggests the temporality of protracted suspension that makes the revolutionary judgement much overdue, its very belatedness also signals the ultimate triumph of arrival points. The path to pink revolution thus marks the trajectory of progress and maturity. The refractions of rainbow light from triangles in the above images are thus marked by a kind of limitless progression and linearity, suggestive of boundless futurity and growth. Their “vigor” is implicitly contrasted with former British colonies whose protracted delays have not produced their own pink revolutions.[12] Take for instance the headline of a report in The Daily O a few weeks after the Supreme Court ruling that declared: “While India Celebrates Partial Strikedown of Section 377, Pakistan Continues to Suffer.”[13] The piece goes on to document a variety of brutal assault cases against transgender people in Pakistan, marking it as the site of primitive risk and violence. Thus while the fate of Pakistan’s queer population is hung in hazy suspension, that of India’s is marked by giddy arrival and democratic potential. The temporal contrast is also played out through literal configurations of growth and linear models of development in which Pakistan is marked by an unruly and primitive infancy in contrast to India’s matured arrival at the altar of legal progress.

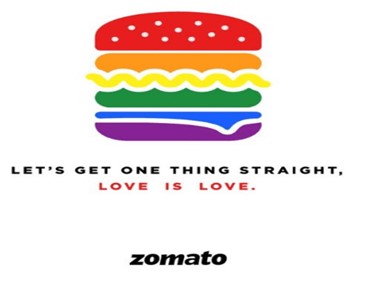

Not surprisingly then, the markers of development that subtend the response to the ruling also recall maturity scripts in a different sense—that of economic growth indexing the profitability of a globalization-oriented India. In the aftermath of the September 6th ruling, food delivery start-ups such as Zomato and Swiggy that have become a ubiquitous marker of “Digital India” joined in the celebrations of the Supreme Court’s reading down of Section 377. Accompanying an image of a seven-tiered rainbow colored slice of cake, Swiggy tweeted a message of solidarity with those celebrating the ruling which said: “It’s not been a piece of cake, but we got there.” The double meanings are not simply restricted to the “piece of cake” pun, but also to arrival points of “getting there,” that allude both to the deliverance of justice against all odds, but also implicitly, to Swiggy’s own promise of food delivery that transgresses space and time. Swiggy thus becomes a microcosm for globalization’s time-space compressions in which the instantaneousness of food delivery subsumes and eventually overcomes all signifiers of delay and lateness. Not to be outdone, rival food delivery company Zomato India tweeted its own celebratory message (“Let’s get one thing straight, love is love”) with its version of the tiered cake—in this instance, a rainbow colored burger (Fig 4). The image of the burger has indexed a kind of globalism ever since the entry of McDonalds became ubiquitous in India since the revolutionary mid-90s. But in order to reconcile to local tastes and ideological demands, McDonalds India immediately launched the “McAloo” potato burger, foregrounding its investment in adapting to local “tradition.”[14] Through McDonalds’ experiments in local reconciliation, the burger is thus no longer exclusively a signifier of the west, but instead a more malleable symbol of global-local flexibility that can acclimate to different ideological needs depending on the requirements of the cultural and material context it might have to navigate. Thus Zomato’s tweet indexes both globalism (India has finally “caught up” to the West) and localism (the celebration of exceptional Indian democracy). The image’s appeal lies in its celebration of pink revolutions—in this instance, queer “love” that also stands in for the love of the burger—a love that must, however, carefully safeguard against any proximity from another kind of pink revolution in the burger’s association with beef consumption if it is to appease Hindu sentiments.

Fig. 4: Zomato

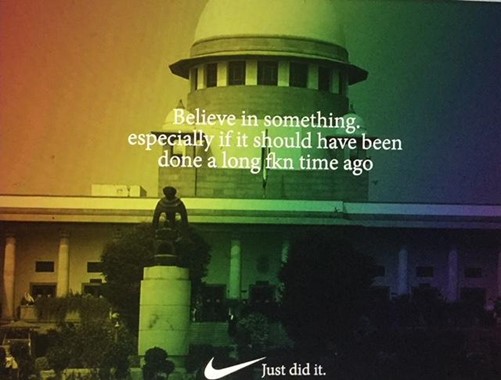

In yet another image that triangulated the logics of temporality with the rainbow “queering” of the Supreme Court building and the power of global branding, the Indian comedy group All India Bakchod’s Instagram page displayed an image of the Supreme Court building awash with a rainbow colored filter (Fig 5). The text on the image boldly proclaims: “Believe in something. especially if it should have been done a long fkn time ago” (sic). Below this message of solidarity is the familiar logo of the Nike swoosh with a marginally altered trademark slogan “just did it.”

Fig. 5

Like several expressions of celebration after the ruling, the above image mobilizes a politics of time to express incredulity at the logics of delay, making the ruling something that should have already been achieved “a long fkn time ago.” Temporal drags, however, are compensated not simply by the victorious culmination of final arrival, but also by brand association with a global sportswear company like Nike that conjures a logic of time that is far removed from the laborious protraction of prolonged delay. Instead, athletic speed and the muscular performativity of achievement become the visual frames that signal the dawning of a new India that has finally rejected the ossifications of antiquated tradition. In a New York Times op-ed entitled “India’s Battle for Same-Sex Love” just a few months before the imminent Supreme Court decision, author Sandip Roy similarly frames LGBT rights in India in the familiar terms of a tug-of-war between antiquity and modernity, or once again, a temporal lag in which “India’s Supreme Court is playing catch-up in a society that seems to have largely moved on.”[15] Like the above Instagram post in which the Nike swoosh stands in for India’s final entry into global modernity, Roy invokes the world as a kind of global witness—those in power recognize that “the world is looking at India,” optimistically anticipating what would eventually be actualized only a few months later: “If Section 377 falls, there will be celebrations not just in India, but also in San Francisco, Toronto, and London.”[16] Roy’s supposition is predicated not simply on the material presence of Indian queers in the diaspora who would welcome the eschewal of state-sanctioned homophobia, but also on the place of India as a nation that is politically and economically connected with the rest of the globe, actualizing its own branding as the world’s largest democracy.

India’s political and economic relations with other global entities hint at the possible emergence of new kinds of triangles that might be forged in the service of national futurity and projects of aspirational modernity. Take, for example, yet another avatar of triangular structures—the emergence of “growth triangles”—a concept that has been mobilized in the context of Southeast Asian nation-states to signal relations of economic reciprocity and foreign management between countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. In her analysis of the politics of flexible citizenship, Aihwa Ong defines growth triangles as “zones of special sovereignty that are arranged through a multinational network of smart partnerships and that exploit cheap labor that exists within the orbit of a global hub such as Singapore.”[17] In keeping with the logics of globalization that both underscore and decentralize the role of the nation, the labor forces in these new zones of sovereignty are accountable to the requirements of private industry rather than nation-states (the fact that these two entities are symbiotically linked, however, also mediates these “new” rules). While the geographic location of India and its political conflicts with bordering nation-states prevent the exact replication of ASESAN country mutual cooperation, it is worth noting that Modi’s economic agendas have often drawn inspiration from Southeast Asian contexts, most obviously, for example, the Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India) that shared its vision with “Keep Singapore Clean” campaigns. More future research needs to be conducted on India’s version of growth triangles that explores the politics of comparative Asian modernities, given the particular structural shapes that mark these formations. For example, India-Pakistan tensions have been mediated by a triangular connection with Chinese investments in economic growth in which the formation of CPEC (China Pakistan Economic Corridor) has been perceived as excluding India’s participation in development projects. Arguing for India’s inclusion in a growth triangle of sorts, Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti asks:

Why can’t we be partners in economic growth and share the benefits of projects like CPEC? Let us move beyond skirmishes. It would make the region a hub of emerging economic opportunities leading to cooperation in trade, commerce, tourism, adventure across the region.[18]

Throughout Pink Revolutions, I have illustrated how the economic is closely braided into the intimate—and so India’s desire for partnership with China indexes a participation in new models of modernity in which sexual politics plays a crucial role.

In this light, the expressions of celebration detailed in this afterword must be seen as more than simply projects of corporate profiteering around newly emerging modes of queer visibility in which Indian companies are capitalizing (quite literally) on the global visibility of the Supreme Court’s ruling. Once again, it might be useful to return to the months just prior to the epistemic moment of “victory” to understand the ideological terms on which modes of sexual belonging were getting articulated. On July 22 2018, The Times of India published “Proud to be Gay” in which it interviewed several out Indian LGBT personalities marked as prominent “professionals.” Despite all of these individuals having reached the apex of success in their chosen professions, their disenfranchisement through Section 377 gets articulated as the only remaining stumbling block that obviates their inclusion into full citizenship. Parmesh Shahani, the head of renowned industrial house Godrej’s Culture Lab, thus points to these mechanisms of exclusion despite being “an honest taxpaying and law-abiding citizen”:

…all these years, I’ve felt less than equal. As someone who deeply loves his country and considers himself a patriot, it is not a good feeling to have this law that makes me a second-class citizen. To think that the law criminalises something as basic as who you choose to love is constitutionally and fundamentally wrong. How can loving someone be a crime?[19]

In the above words, disenfranchisement is expressed in affective terms—as “not a good feeling,” divorced from any material articulation of political economy or criminal persecution. Feeling bad is a consequence of the criminalization of gay sex, but more accurately in the above framework, it is an unequal system of exchange that refuses to grant full citizenship to those like Shahani who do not get their “due share” despite never having broken the law and having paid their fair share of taxes. In the realm of feelings, Section 377 is thus framed as a matter of unrequited love in which national desire is met with an indifferent nation state from which Shahani yearns nothing more than simple acknowledgement. The affective arguments thus continue in the next paragraph when Shahani suggests that if only Section 377 were repealed he would “feel validated, respected, and included.”[20] Once again, the generational framing between young and old India is invoked, suggesting that college-aged Indians “think it’s dumb to have anything like 377 in the year 2018.”[21] Thus while the nation’s heart is in the right place, its laws are once again passé and out of step with global standards—playing catch up to its more current cosmopolitan and modernist inclusivity. If celebrations of the Supreme Court’s ruling were framed in the language of national sentimentality, it is not surprising that Shahani resorts to the humanizing of corporations in his concluding remarks. Commenting on the importance of LGBT-friendly policies in India’s major industrial companies, Shahani suggests that “there are already 30-40 companies in India that have adopted LGBT-friendly policies. Once 377 goes, I can guarantee that there will be a hundred more such companies that come out.”[22] Not only are corporations thus framed as beacons of accelerated development and freedom (with which the lagging courts must draw level with), they are also humanized as those that might be able to “come out”—the double meaning of which is not without significance.

Not all of the responses to or rationales for reading down Section 377 were framed in terms of affective or sentimentalizing rhetoric described above. In a viral tweet immediately following the ruling that particularly resonated with postcolonial critiques and colonial historical accounts that have foregrounded the genealogies of sodomy laws, Shahmir Sanni suggested that it would be myopic to read the Supreme Court decision simply as India finally “catching up” to the West: “From gay Sufi lovers to Hindu transgender women. India’s sexual fluidity was always a dirty, barbaric concept to its western invaders and it is crucial for the LGBTQ community here in the west to understand this. This isn’t India becoming ‘westernised’. It’s India decolonizing” (@shahmiruk, September 6, 2018). In addressing the “LGBTQ community here,” Sanni’s audience is the UK, the very site at which one can genealogically trace the colonial codification of Section 377 in 19th century British-ruled India. His critique thus implicitly addresses the irony in the UK welcoming India into the “westernized” democratic club of nations who have stepped into the 21st century through progressive jurisprudence. Even while Sanni is right to complicate a reading of the ruling as a mimetic copy of a progressive west, the desire to frame the revolutionary judgement through the singular lens of resistance performs its own elisions and foreclosures.[23] Center-periphery geometries of power often risk overdetermining the non-west as a site of resistance. The reading of the Supreme Court ruling as a symptom of decoloniality erases its operations as an apparatus that continues colonial projects under the alibi of postcoloniality through which it forestalls insurgent practices. The sweeping gesture that reads the Supreme Court verdict through the lens of “India decolonizing” thus works to subsume a moment in which colonial triangles in the occupation of Kashmir (between militant Indian nationalism, Islamic fundamentalism, and global investments in the occupied territory) brush up against the triangulations of pink revolutions in which the latter can then serve as smokescreens for the former.

In a tongue in cheek response to the ruling that revealed a more tempered reaction than the euphoria of supposed decoloniality, another twitter user wrote: “Now all Indians can love people of any gender from their caste” (@iimcomic, September 6, 2018). Perhaps in a wittier and certainly more pithy form than this afterword, the tweet gets at the crux of what I have been trying to gesture toward in this afterword—i.e. a consideration of the detritus of the law’s afterlife that still remains in the wake of euphoric pronouncements. I do not want to simply jettison such modes of euphoria given the long labor of queer and feminist activism that led to the verdict—which should, of course, be framed as an outcome of such labor and not the magnanimous character of India’s judicial system. Instead, I want to brush these modes of euphoria up against, not just the failure of state redress in other contexts, but the state’s mobilization of law to produce violence and sites of dispossession. Modes of apparent redress can then actually function as a “re-dressing” of the law so that forms of coloniality can pass as revolutionary decoloniality, even as law is mobilized by the state to buttress nationalism through charges of “sedition” against dissenting subjects. How then do these celebrations of “Indian freedom” in the context of “queer love” become a way of dragging us back into nationalism? This framing of queer “victory” as a kind of dragging—in its invocation of temporal delay and a “drag” on time—runs counter to its temporal logics of speed and achievement—the “finally” “at last” and “just did it” in the celebrations above.

The push and pull of delay and speed gestures toward multiple temporalities that subtend Indian postcoloniality—time that is “made up of disturbances” in the words of Ayana Roy.[24] It is only when we recognize these temporal clashes as disturbing forms of bio-necro collaborations rather than as benign reconciliations of an “old” and “new” or of local and global that we can begin to unravel the triangulated knots of pink revolutions. Rather than “walk(ing) into the disciplinary regime of the state,” what might it mean to contravene the logics of nationalist drag? To imagine a different kind of revolution that might allow us to “drag” the nation in multiple senses of the term? Rather than pledging allegiance to the Indian flag in the age of sedition charges, compulsory patriotism, and Hindu fundamentalism, the time has come to drag ourselves out of nationalism even as we are seduced by its inclusive accommodations.

The above essay is a modified revision of the conclusion to Pink Revolutions: Globalization, Hindutva, and Queer Triangles in Contemporary India (Copyright Northwestern University Press, 2021). The original version appears as “Afterword: A Delayed Postscript”

[1]Notes: In the larger book, I argue that the idea of “revolution” is rendered fungible with reform within the logics of economic liberalization in the early 90’s in India, which cast market reform and neoliberal policy as “radical” and “revolutionary.” Thus pink “revolutions” is not an uncritical celebration of LGBT visibility in India, but indexes how it gets knotted with India’s global modernity aspirations and “worlding” ambitions.

[2] “Supreme Court Strikes Down Law Criminalizing Homosexuality,” The Hindu.

[3] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Translators Preface,” Of Grammatology, ix.

[4] Adam Roberts, India: Superfast Primetime Nation.

[5] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Translators Preface,” ix.

[7] Elizabeth Flock, “The Law Breaker.” Forbes India. The quote is from Anjali Gopalan, commenting on the reading down of Section 377 by the Delhi High Court in 2009.

[8] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Outside in the Teaching Machine, 5.

[9] Lauren Berlant, The Queen of American Goes to Washington City, 11.

[10] Ashley Tellis and Sruti Bala, The Global Trajectories of Queerness: Re-thinking Same-Sex Politics in the Global South, 21.

[11] Jyoti Puri, “Genderqueer Perspectives,” Law Like Love, 204.

[12] In Queer Activism in India, Naisargi Dave points to the ABVA’s (AIDS Bhedbav Virodhi Andolan) 1994 petition against Section 377 in which it resorts to “an uncharacteristic homonationalist display” pointing to the law’s continued relevance making India keep the “backward company of Pakistan, Malaysia, and Singapore” (173).

[13] Pathikrit Sanyal, “While India Celebrates Partial Strikedown of Section 377, Pakistan Continues to Suffer,” The Daily O.

[14] McDonalds in India does not use beef in their burgers and assures Indian consumers that their kitchens that make chicken patties are carefully sequestered from vegetarian-only spaces)

[15] Sandip Roy, “India’s Battle for Same-Sex Love” The New York Times.

[17] Aihwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship, 222.

[18] Quoted in Harsh V. Pant, “Will India, China, and Pakistan ever Move Beyond Skirmishes to be Partners in Economic Growth?” Thisismoney.co.uk

[19] “Proud to be Gay,” The Times of India

[23] The framing of jurisprudence as the site of queer decolonization (often defined in economic terms as exemplified in the Swiggy and Zomato ads) dovetails seamlessly with the nationalist and even internationalist bromide of India as the “world’s largest democracy.” In Stages of Capital, Ritu Birla draws close attention to the relationship between the law and political economy, illustrating how an effective form of sophisticated jurisprudence is viewed as an essential requirement for market stability and India’s unique relation to democratic exceptionalism. Conventional historiographies have narrated colonial history through the lens of indigenous adaptability—i.e. like the railways and the English language, colonialism conferred the endowment of law, which was then “translated” in accordance with vernacular needs. Birla’s account of the beginning of the 20th century, however, paints a more complicated picture in which vernacular or indigenous practitioners of capitalism were seen as impediments to progress within legal discourses attempting to standardize market practice. Birla’s account thus charts “the legal production of ‘the market’ as a supra-local object of governance, as an abstract model for the public, and as a stage for cultural politics” (3). The colonial history of Indian law and its central place in the constitution of markets make the contemporary assertion of legalism as a site of decolonialism worthy of a genealogical unpacking.

[24] Ananya Roy, Worlding Cities, 330.

Bibliography

Dave, Naisargi. Queer Activism in India: A Story in the Anthropology of Ethics. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012.

Berlant, Lauren. The Queen of America Goes to Washington D.C: Essays on Sex and Citizenship. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1997.

Birla, Ritu. Stages of Capital: Law, Culture, and Market Governance in Late Colonial India, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009.

Flock, Elizabeth. 2009. “The Law Breaker.” Forbes India, December 26.

Ong, Aihwa. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999.

Pant, V. Harsh. “Will India, China, and Pakistan ever Move Beyond Skirmishes to be Partners in Economic Growth?” Thisismoney.co.uk, March 31 2017, https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/indiahome/indianews/article-4366212/Will-India-China-Pakistan-economic-partners.html

Puri, Jyoti. “Genderqueer Perspectives: Sameness and Difference in Sections 375/6 and Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code,” Law Like Love” Queer Perspectives on Law edited by Arvind Narrain and Alok Gupta. New Delhi: Yoda Press, 203-227.

Roy, Ananya and Aihwa Ong. Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Roy, Sandip. ““India’s Battle for Same-Sex Love,” The New York Times, July 17, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/17/opinion/india-same-sex-love.html

“Supreme Court Strikes Down Law Criminalizing Homosexuality,” The Hindu. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/homosexuality-decriminalised/article24879339.ece

Sanyal, Pathikrit. “While India Celebrates Partial Strikedown of Section 377, Pakistan Continues to Suffer,” September 10, 2018, The Daily O.

Tellis, Ashley and Sruti Bala, The Global Trajectories of Queerness: Re-thinking Same-Sex Politics in the Global South. Leiden and Boston: Brill Rodopi, 2015.

Nishant Shahani is Associate Professor in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and the Department of English at Washington State University. His teaching and research interests focus on LGBT Studies, queer theory, AIDS historiographies, and transnational sexualities. He is the author of Queer Retrosexualities: The Politics of Reparative Return (2013) and Pink Revolutions :Globalization, Hindutva, and Queer Triangles in Contemporary India (2021). He is also co-editor of AIDS and the Distribution of Crises(2020). He has published articles in venues such as GLQ, Modern Fiction Studies, Genders, Postcolonial Studies, Journal of Popular Culture, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, and QED: A Journal of LGBTQ World Making.