Astarte Rowe

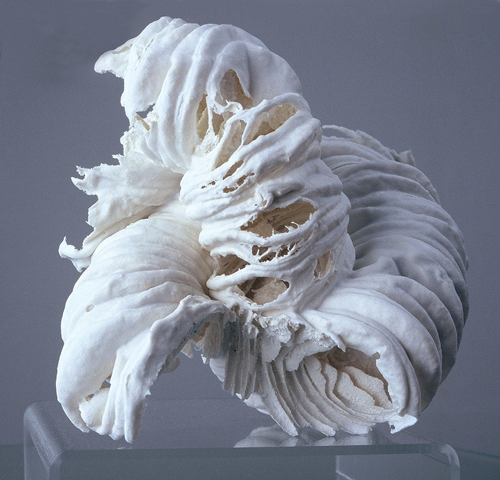

Porcelain Skins (series), 2006, Porcelain, cotton swabs, 7 x 6 x 6 inches. Courtesy the artist.

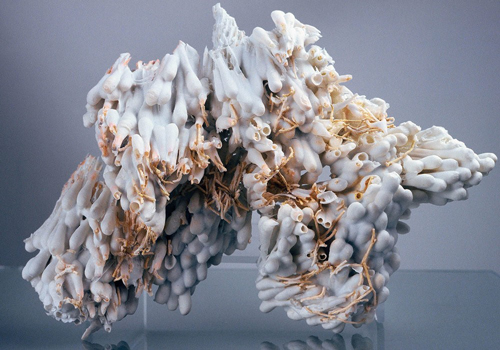

Jessica Drenk’s biomorphic sculptures push materials such as personal hygiene items – gauze, toilet paper, cotton buds, and toothpicks – to their point of organic saturation, thereby simulating organs, micro-cellular worlds, and geological stratifications. Yet Drenk is just as concerned with switching the direction of organic flows, such as when she converts slim cuttings of wood pine into a digital matrix of binary code. Other creations involve shaping books into fossilized records of geologic life, or using waxed book strips to create an extended cerebellum – thus relying on the brain’s cognitive faculty to ‘read’ and ‘interpret’ its own aesthetic disembodiment or lobotomy. All such mechanisms are invested in interrogating organic/inorganic distinctions. Symbiogenesis – the co-evolution of different species – is deployed in Drenk’s work to excavate and transcribe a contingent ‘image of thought’ distributed and elaborated across organic, plastic, informatic, and inorganic strata. According to Drenk, ‘on a long enough time scale, there is no difference between manmade and nature.’

Astarte Rowe: One of the most fascinating aspects of your art is how it engages with the question of materiality. For those who are less familiar with your work, it may be described as an intervention into the materiality of objects and nature. Could you tell us a bit more about how this profound inquiry into matter defines the aesthetics you have been developing over the course of your career?

Jessica Drenk: In my work, the sculpture’s material is not just a medium for conveying content, it is also a large part of the content. I use each material as the starting point for creativity, and try many different ways of changing and manipulating that material until it is brought into line with my personal aesthetics. Aesthetically, I like shapes that are somewhat chaotic, somewhat organized, very complicated and textural, and I have a very strong affinity for the shapes and patterns of nature. So I may start with a very simple material, but then work and rework it until it becomes something complex and new. In the end, the content of the piece lies somewhere between the original material and the shape I have made out of that material.

AR: The sculptures in the Implement and Formation series are very compelling. It is fascinating to see a seemingly prosaic object like the pencil being used as the building block for structures that resemble mineral formations or even shell-secretions. What inspired your use of standard pencils for the Implement and Formation series?

Implement 4, 2012, pencils, 18 x 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy the artist.

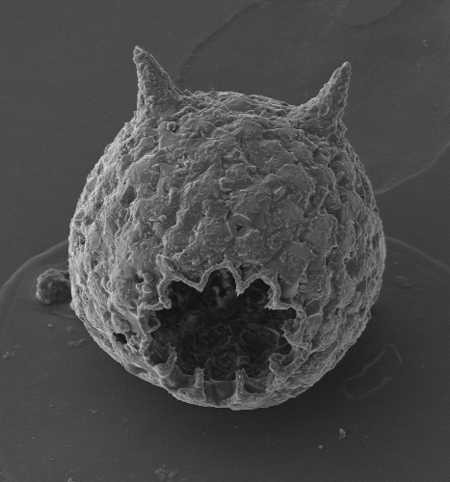

Mediolus corona, 2011, Scanning Electron Microscope, 115 microns, Lake Mount Hope, Toronto. Courtesy Patterson Research Group, Carleton University.

JD: Pencils have a fascinating shape, because they are highly geometric, but that hexagonal shape can also be found in nature: in wasp nests and beehives, as well as in columnar basalt (rock) formations. The hexagons also fit together neatly, so the idea of gluing them together seemed natural. But the aspect of pencils that interested me most was the idea of sanding them to see their inside, and to expose the graphite within. As the pieces evolved, their inside/outside duality became a feature: in the interior space of the sculpture you see the exterior of the pencils, while on the exterior surface of the sculpture, you see the inside of the pencils.

Implement 4, 2012, pencils, 18 x 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy the artist.

AR: As a follow-up question, the reshaping of everyday objects into chthonic and organic forms is very disorienting, even alienating, in that it undermines the utilitarian functionality of, say, a common writing implement, and somehow de-possesses geometry of its instrumental rationality. You do not seem to be abolishing geometry (as with the Implement series), or even binary code (as with Procession 23), but complicating our tendency to isolate organic and inorganic regimes from one another. Is your artistic praxis involved in spawning a different world, or at least a different relation to the world? If so, can you tell us a bit more about this trajectory?

Procession 23 (detail), 2011, Pine wood, 60 x 20 inches. Courtesy the artist.

JD: It is meant to be exactly as you say, very alienating. But the aesthetics of the work are meant to pull you in, to be pleasing and make you want to look and examine. I am trying to get you to see the work as one kind of object, and then to look more closely and realize it is in fact an entirely different and opposing object. And yes, it is exactly what you said above: I’m trying to complicate our definitions of ‘man-made’ and ‘natural’ by presenting them both in the same art object.

AR: Do you select standard materials (books, Q-tips, gauze, toilet paper, pencils, etc.) based on their potential to be re-shaped and processed beyond their original forms and intended uses? And are you invested in narrating and archiving an alternate life and dimension of these materials? If so, why?

JD: Certainly, malleability is one criterion for selecting materials. Generally I like to work with materials that come in multiples, so I can manipulate large numbers of shapes into works of visual richness. I also consider my emotional association with my materials: the love and respect I have for books versus the disposability and bodily associations of toilet paper and Q-tips. For each material my goal is to push it beyond itself and to transform it into something new, while still being recognizable as the old. This blurs the lines between categories and makes you consider the life cycle of objects.

Porcelain Skins (series), 2006, Porcelain, Q-tips, 7 x 5 x 4 inches. Courtesy the artist.

AR: The kind of discourse that has framed such movements as Eco-Art has aimed at centralizing the role of humans in the preservation of nature; or protesting the commercialization of art as with Land Art. 7000 Eichen / 7000 Oaks (1982), by Joseph Beuys, is a famous example that embodies both these strategies. Yet, although your art is deeply influenced by nature, I do not get the sense that it can so easily be classified within these categories. What image of nature do you feel your artworks convey?

JD: A central premise of my work is the notion that we, humans, are not separate from nature, we are a part of nature. Though we have figured out how to harness and manipulate natural elements to create our man-made objects and environments, I don’t think we have yet fully understood or accepted ourselves as a part of the natural environment.

AR: Lastly, I wonder if you could comment on whether the fact that a curator has involved you in a group show with shell-building amoebas, which have been constructing cases for 720 million years, says anything at all about your artworks, inspiration, or practice.

JD: A large part of my inspiration comes from science and natural history, and I am awed by the shapes and patterns created in nature and by natural organisms. I think nature is one of the best artists, so I am happy to be included in an exhibition with the ‘work’ of the shell-building amoebas.

Montana native Jessica Drenk (b. 1980) received her MFA in 3D Art from the University of Arizona. The recipient of, among other awards, the Artist Project Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts and the Contemporary Sculpture Award from the International Sculpture Centre, her work is also part of corporate and public collections such as Fidelity Investments and the Yale University Art Gallery.

Dr. Astarte Rowe received her PhD in Art History from the University of Melbourne. Her articles appear in the International Journal of the Image, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Art + Australia, and World Art.