Stephanie Youngblood

Lili Reynaud-Dewar, My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class). SFU SCA Seminar with Alexandra Best, Kayla Elderton, Jorma Kujala, Siena Locher-Lo, Chris Mark, Emily Marston, Weifeng Tang, Cory Woodcock, Sitong Wu, Viki Wu, Nicholas Yu. Installation view, Audain Gallery, 2015. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

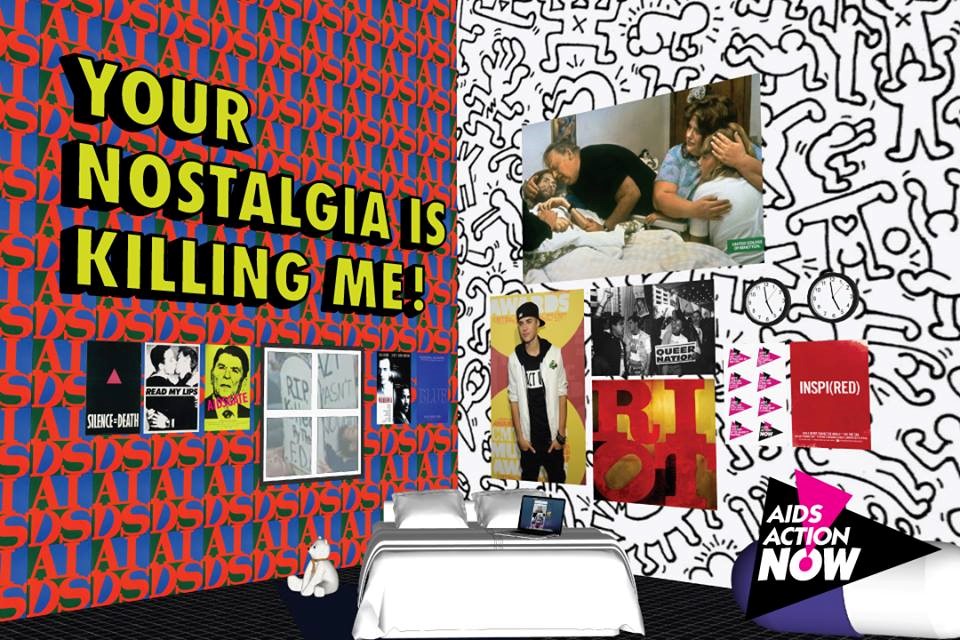

Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin, Your Nostalgia is Killing Me, 2013, Digital/Google Sketchup. Image courtesy AIDS Action Now and Poster/VIRUS (Toronto).

I first started thinking about nostalgia and the AIDS crisis in response to the various public testimonies that have circulated over the last few years, in films and documentaries like The Normal Heart, We Were Here, United in Anger: A History of ACT-UP, and How to Survive a Plague, and through exhibits such as the New Museum’s 2014 exhibition NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star and the Whitney Museum of American Art’s I, You, Wed: Art and AIDS in 2013. While this turn to the lived-realities of AIDS in the 1980s has been generally welcome, the dark side of this creeping nostalgia is also made strikingly evident in the 2013 poster by Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin for Toronto’s AIDS Action Now that you see here; both the poster and the discussion session with Visual Aids and the New York Public Library that followed in 2014 are titled ‘Your Nostalgia is Killing Me!’[1] Given these two polarities then, my question is: can nostalgia be political? And, specifically, can it be political within the context of the AIDS crisis?

I want to note here that allowing the conversation around AIDS to be dominated by how the crisis affected gay men in New York has potentially damaging repercussions across the art and activism spectrum. Yet, the ways in which we talk about the crisis as it emerged in the 1980s continues to have an impact on how we think about the crisis more broadly today and the questions and problems this emphasis raises are productive tensions that are useful to continue to explore.

In my broader project, I explore the relationship between the present and the past through the framework of testimony, or through testimonial literature, which, for me, means attending to testimony’s rhetorical figures, which, as Sara Guyer has argued, are also the figures of lyric.[2] More specifically, I explore how figures of speech associated with voice, apostrophe, prosopopoeial and catachresis all testify to an event and draw attention to their own formal conventions. I say this here only to emphasize that I think the formal dimensions of testimony, rather than its content, are determinant of testimony’s political valence, and I am hoping to return to this question of form at the end of this essay.

Thinking about the politics of testimony can be challenging, however, as testimony tends to get lumped under the broader umbrella of the so-called ethical turn and, as such, is often a target of the same critiques that political theorists have leveled against that turn: an overreliance on consensus, a privileging of the unsayable, and an emphasis on the impossibility of representation. For example, in his essay ‘The Ethical Turn of Aesthetics and Politics,’ Jacques Rancière bemoans ‘the reduction of art to the ethical witnessing of catastrophe’ because trauma and witnessing, as conceptual frameworks that emphasize unrepresentability, destroy the possibility for the distinctions and disagreement—the dissensus—that Rancière argues is necessary for politics to occur.[3] Aesthetics are thus political only when ‘they stage a conflict between two regimes of sense, two sensory worlds,’ rather than through the concordance or agreement that testimony ostensibly brings.[4]

While I am generally persuaded by this definition of politics, I resist the idea that testimony and other forms of contemporary memorialization are by definition antithetical to politics, as Rancière defines it. My attempt here is to think through nostalgia’s place in this ethico-political divide, which is also connected to my attempts to think through art and politics from within (rather than against) the aesthetics of testimony, despite the critiques against testimony (and its supposed connection to the ethical turn) that Rancière brings. At the same time, I think Rancière’s work is particularly interesting to bring into our conversation here about art and politics in the time of HIV/AIDS, given that, as he puts it, ‘the problem, first of all, is to create some breathing room, to loosen the bonds that enclose spectacles within a form of visibility, bodies within an estimation of their capacity, and possibility within the machine that makes the “state of things” seem evident, unquestionable,’ (a perspective we might bring to the history of ACT-UP).[5] So, my question then becomes: under what conditions is testimony political? And is there any way that nostalgia could be one of those conditions that allows politics (as a disruption of the partition of the sensible) to emerge?

Nostalgia may seem like a strange concept to turn to for disruption, given that it is almost always associated with a return to the familiar. ‘Nostalgia’ was originally a medical term, coined in the seventeenth century, which brought together the Greek word for pain/grief/distress with the word for homecoming; it literally means, ‘a painful longing to return home,’ and was originally used to describe a medical condition, namely concerning Swiss soldiers, and their intense homesickness when fighting abroad; it retained this specific biomedical association until the twentieth century. Currently, the OED defines it as an ‘acute longing for familiar surroundings, esp. regarded as a medical condition; homesickness’ and even Don Draper, from Mad Men, calls it ‘pain from an old wound.’[6] Nostalgia thus seems to tie the bodily experience of the present with an imaginative attachment to a vision of the past that is unmoored from present realities.

This unmooring of the past in relation to the bodily realities of the present played out recently in American culture. In March 2016, there was a flurry of media activity around remarks that Hillary Clinton made following the death of Nancy Reagan, in which Clinton, unprompted, told MSNBC reporter Andrea Mitchell that ‘it may be hard for your viewers to remember how difficult it was for people to talk about HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. And because of both President and Mrs. Reagan—in particular Mrs. Reagan—we started a national conversation.’[7]

The reaction to her comments was, unsurprisingly and well deservedly, immediate and fierce. The New Yorker, Medium, Jezebel, Slate, The Guardian, The Nation (and the list goes on) weighed in on the comments that Clinton made, quite rightly pointing out how erroneous and ridiculous it was to credit the Reagans with bringing any kind of helpful attention to the AIDS crisis.[8] For my purposes here, however, I won’t dwell on Clinton’s initial comments, or on her retraction, so much as how I want to focus on how Steven Thrasher, writing for The Guardian, summarized the situation. In his article from 11 March 2016, Thrasher writes that, ‘I fear she was engaging in a kind of dog-whistling, using the moment of Nancy Reagan’s death to appeal to voters who nostalgically loved the Reagans and dream of morning in America again.’[9] Here, Thrasher ties a false perception of the history of AIDS to nostalgia for the Reagan administration and for the supposed prosperity of those times; as Thrasher writes, ‘I have been frightened for some time that the crisis of AIDS is not over, especially for black America, and yet it has again largely been erased from our national political consciousness,’ due, in part, to the nostalgia that Clinton invokes. In other words, nostalgia here is tied to erasure.

Thrasher’s emphasis on nostalgia is strikes me, as it seems to echo, though in a very different register, the ways in which the 1980s has also been playing out in recent cultural efforts to document the early years of HIV/AIDS. Over the last few years, a number of films and documentaries dealing with the experience of AIDS in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s have emerged, with a specific emphasis on the ways in which various queer communities themselves responded to the crisis. Opposing Philadelphia (1993), which depicted the ravages of the disease as it effected an individual, is 2013’s Dallas Buyers Club and 2014’s The Normal Heart; both films focused on the ways in which gay men themselves responded to and confronted the crisis (rather than simply suffered with it). Similarly, around the thirtieth anniversary of the official outbreak, David Weissman brought We Were Here (2011), an elegiac documentary film that focuses on the early outbreak in San Francisco; it charts the existence of various queer communities before and during the AIDS crisis, then turns to the work done by these groups to provide community support, social services, and medical care in the face of massive social and governmental neglect. Similarly, David France’s 2012 How to Survive a Plague, composed almost entirely of vintage footage, begins in 1987, and traces the efforts of ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and TAG (Treatment Action Group) to reform research in and access to relevant drug and care practices at both the local and federal levels. Both of these latter films having opened to broadly positive reviews, are examples of what Bill Nichols describes as documentaries in the ‘observational mode,’ or in the tradition of direct cinema or cinéma vérité,[10] and seem to mark, in Andrew Holleran’s words, ‘a nostalgia for more heroic days,’ when it seems as if individuals, joined together in collective action, could effect changes in governmental policy. In other words, direct cinema, tied as it is to a realist technique that emphasizes ‘actuality’ through the naturalness of dialogue and the authenticity of action, is directly tied to nostalgia for that now-passed actuality.

Eric Ames, however, describes this type of observational cinema as ‘a repudiated mode of filmmaking, owing to its historical association with reportage, its institutional identity as a branch of journalism, and its discursive claims to “truth,” “reality,” and “authenticity.”’[11] In other words, as a mode of documentary film-making, this type of testimonial work and the nostalgia which seems to be its unavoidable effect, seems to remain entrenched in forms that privilege the illusion of transparency and presence, rather than their aesthetic conventions, in the pursuit of political, ethical or activist agendas, and are thus contrary to the type of dissensus that Rancière says defines the political as such.

At the same time however, Rancière also writes about nostalgia in an article entitled ‘The Factory of Nostalgia,’ where he discusses the ways in which the nostalgic qualities of historical accounts of the working class allow the critic to remain distinct from his subjects and thus encourages a false division between the subject and object of radical movements. In terms of how HIV/AIDS played out in response to Clinton’s remarks, it seems that, across various perspectives, nostalgia was tied to legacy, and specifically to biomedical legacies (for Clinton it was stem cells; for the films and documentaries, it was ACT-UP and quick, useful access to medicine and medical trials). I wonder if, in some ways, both of these strands of nostalgia are nostalgic for a time in which the individual could affect significant biopolitical change. So, one of the main effects that I’d like to keep thinking about is what I am calling ‘biopolitical nostalgia,’ or what I understand as a kind of nostalgia for a moment in time when it seemed that we, as individuals or a collection, could successively intervene in the institutional practices and procedures of biomedicine; to me, this ties into discussions about whether we reconceptualize and reengage the radical past (ACT-UP and TAG, in this case) in a way that does not simply monumentalize the past but instead engages current biomedical realities.

Here, I have been influenced by Janina Kehr’s more recent work on ‘biopolitical nostalgia,’ though for her, that nostalgia is more for ‘state-funded medicine and public health,’ though she does tie this nostalgia (her research focuses on contemporary Spain) to ACT-UP and the AIDS epidemic in the United States, For example, writing in 2014 about the infection of a nurse in Spain with the Ebola virus, Kehr notes that:

Such accusations [about threats of infection] conjure images of the late 1980s and early 1990s AIDS movements in the U.S., when a pharmaceutical treatment was not yet publicly available. ‘Die-ins,’ posters showing names and faces of AIDS victims subtitled ‘Killed by the Government,’ and other highly symbolic expressions and events surrounding AIDS activism have subsequently become part of a global protest repertoire against governmental politics of epidemic denial and ignorance. Moreover, in European countries, such public displays of discontent with governmental health policies have recently become powerful means of contesting the politics of public service privatization and austerity measures, at least in countries with national health services, like Spain and the U.K.’[12]

Thus, in crafting the notion of ‘biopolitical nostalgia,’ Kehr emphasizes how the emotional attachment to a ‘phantasmatic’ view of healthcare in the past structures citizens’ identities and motivates their political action in the present. In other words, she finds something politically recuperative in this nostalgia for by-gone days of state-funded health services.

And so, to return to the poster I referenced earlier, I think Your Nostalgia is Killing Me! both critiques nostalgia for the radical past even as it deploys it as a means to engage the present. ‘It is not the remembering and it is neither the history, nor the material culture nor the valorization of the battles won and lost that impedes our movement forward,’ write Chevalier and Bradley-Perrin for their poster/VIRUS artist statement, ‘but rather the unpinning of our past from the circumstances from which the fights were born.’ As Bradley-Perrin also notes: ‘what initially drew me into conversations around nostalgia was its incongruity with an experience in the present and I feel like this is really the deadly part. In what ways is an aesthetically prepackaged memory of AIDS, the AIDS movement, and particular moments of the crisis occupying a critical discussion space which could be better filled with the pressing issues of the “now moment” of AIDS?’ As he goes on to say (echoing Rancière’s own critique of our nostalgic attachment to the illusory past of the factory worker):

when we think about the 80’s and the 90’s and we talk about the ashes action and the public funerals and we uproot them from their historical specificity- when we say things are different for us now- we are not thinking about the ways in which criminalization is exacting a ‘death’ on poz people today… What we are left with are palatable and commodified ‘memory’ representative of the past in the present. This reproduces many of the inequities of the past in the present telling of the story, the same people get left out as before and the same experiences get privileged.

In other words, for these artists, nostalgia unmoors events from their context and reduces that context to a single visual or narrative, foreclosing the ‘complication of narrative, or the fracturing of the distribution of the sensible, that politically efficacious art demands. At the same time, however, the poster’s citational practice, referencing as it does the various iconic aesthetic practices associated with ACT-UP and other activist organizations, animates contemporary discussions concerning HIV/AIDS through the very mechanisms it asks us to critique.

Abruptly, this brings me to musical theater. Here, at the end of this short thought experiment, I want to suggest that musicals, and specifically William Finn’s 2003 Elegies, have the potential to stage the tensions inherent in nostalgia in politically efficacious ways. This claim may seem counter-intuitive, if, as Rebecca Ann Rugg has argued, ‘nostalgia is the prime dramaturgical mode of musical theater [and that] …on the surface, musicals present a historically simplified America.’[13] But, in 2003, William Finn composed a song cycle entitled Elegies, an autobiographical cycle of 19 songs that trace and commemorate family and friends of Finn who have died. While he included a wide range of people here, the cycle loosely coheres around losses he experienced, first, from AIDS and, second, from 9/11.[14] This seeming conflation might at first seem odd or even insupportable, but, it’s worth noting that, in fact, these two events are often referenced side by side, in contexts ranging from popular culture to political philosophy; for Finn, the pairing of these events, however, seems to be more about the resonating experiences of loss than it is the explicit engagement with the geopolitical similarities of the events. In fact, the content of Elegies does, on the one hand, lend itself to memorialization along the lines of the nostalgia critiqued by Rugg (a nostalgia for a time when life proliferated in its seemingly infinite variety of friends, family, co-workers, lovers, composers, neighbors and pets), but on the other hand, the show stages a suspicion of nostalgia on both the level of content and form, even as it revels in the hyperbole of its ostensibly nostalgic voice. Elegies, in fact, ends with the line ‘the ending’s not the story,’ emphasizing that the forms of representation through which we remember a life (a song, a narrative) are distinct from and not equal to the historical experience of that life. More significantly, however, is the show’s formal arrangement of the song cycle, tying as it does somewhat discrete experiences (the various elegies) into one overall, but loosely gathered theme, all through the hyperbolic voice of musical theater.

I think there is more to say here, perhaps by reading nostalgia in Elegies alongside and in contrast to the 1996 musical Rent, but for now, I’ll note that, for Your Nostalgia is Killing Me! the problem with nostalgia is that it invokes the past without an appropriate attention to context and thus to how the context of the past develops into the context (and experience) of the present; nostalgia is connected to erasure, even if it is invoked in the process of remembering.[15] Similarly, for Rancière writing in ‘The Nostalgia Factory,’ the problem with nostalgia is similar, in that an attachment to one image of the past suggests a presence and transparency that cannot help but be illusory and, as such, ignore the perceptual regimes that in fact create the meaning that we take as self-evident in that image; politics, according to Rancière, can only emerge when we disrupt the seeming transparency of that visibility, a disruption that seems to be beyond the scope of nostalgia’s effects.[16]

But, for Kehr (as with Boym), nostalgia is a way in which an attachment to the past can be redeployed and reframed for the purposes of the present. She sees in ACT-UP, not a model for how we used to be powerful, but as a mechanism by which power can continue to be applied and reapplied in a new present context. Here, we might think of Walter Benjamin’s point that ‘the past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again…For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.’[17] Here, Benjamin also suggests that our readings of the past must pay attention to context, both past and present, but at the same time, nostalgia, understood as the unexpected and involuntary resurgence of memories of the past into an experience of the present, brings with it its own disruptive potential. As Frederic Jameson writes (in relation to Benjamin), ‘but if nostalgia as a political motivation is most frequently associated with fascism, there is no reason why a nostalgia conscious of itself, a lucid and remorseless dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of some remembered plenitude, cannot furnish as adequate a revolutionary stimulus as any other.’[18] So, what I would like to suggest is that nostalgia, at least as I see it circulating visually in the Poster/VIRUS art piece and aurally in Elegies, has the potential to unmoor AIDS from its familiar context without ignoring that context entirely, a simultaneity that might then allow mourning to emerge even as it encourages skepticism towards what we think we know of even our most valued past.

[1] See Visual AIDS (https://www.visualaids.org/events/detail/your-nostalgia-is-killing-me-a-catalyst-for-conversation-about-aids-and-vis) for links to both the poster and the various discussions/interviews it has motivated. Furthermore, the poster also inspired a film series and exhibition at Queensland Art Gallery in December 2014, in honor of World AIDS Day; see http://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/your-nostalgia-is-killing-me/.

[2] See Guyer, Sara. Romanticism after Auschwitz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

[3] Rancière, Jacques.‘The Ethical Turn of Aesthetics and Politics’, Critical Horizons, 7.1, 2006, 12.

[5] Rancière, Jacques, Fulvia Carnevale and John Kelsey. ‘Art of the possible: Fulvia Carnevale and John Kelsey in conversation with Jacques Rancière’, Artforum, March 2007.

[6] In her book The Future of Nostalgia, however, Svetlana Boym traces the history of nostalgia, particularly as it emerges in post-Communist cities; there, she defines nostalgia both as ‘a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed, but which first emerged ‘from medicine, not poetry or politics,’ and was thus the biomedical production of ‘”erroneous representations” that caused the afflicted to lose touch with the present.’ Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), xiii, 3.

[7] Hillary Clinton. Interview. MSNBC. March 11, 2016.

[8] For example, Sam Biddle on Gawker wrote that ‘It’s almost tempting to interpret this as withering, devastating sarcasm. The Reagans “started a national conversation about AIDS” in the same sense that George W. Bush “started a national conversation’ about Iraq”’ with a headline reading ‘Hillary Clinton’s Reagan AIDS Revisionism is Shocking, Insulting, and Utterly Inexplicable.’ see Gawker, 11 March 11 2016, blog. Michelle Goldberg’s headline in Slate reads ‘Hillary Clinton Praises Reagans for Starting “a National Conversation” About AIDS. That’s Insane’ and, in The Nation, Richard Kim wrote that “this [Clinton’s comment] is a bizarre and historically inaccurate statement, to say the least. It’s the equivalent of lauding George Wallace for starting a national conversation on segregation.’ See Slate, 11 March 2016, and Richard Kim, ‘Gay Men Feel Hillary Clinton’s Pain – But Does She Feel Ours?’ The Nation, 11 March 2016.

[9] Thrasher, Steven W. ‘Clinton’s comments on the Reagans and Aids demand more than apology’, The Guardian 11 March 2016.

[10] Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001). Furthermore, while direct cinema and cinéma vérité are often used interchangeably to describe documentary films that use the narrative form to ‘offer…a close relationship to life as it is being lived,’ with an illusion of transparency and objectivity. These techniques do in fact have important distinctions, one of which is the level at which the film-makers are actively involved in the subject matter being filmed, and thus the degree to which a claim of objectivity is made. Regardless of these distinctions, however, both of these modes rely on a realist technique that emphasizes ‘actuality’ through the naturalness of dialogue and the authenticity of action. In contrast to these traditions, which obviously inform the AIDS documentaries mentioned above, are the films of, for example, Werner Herzog, who rejects cinéma vérité for its reliance on ‘the surface facts.’ See Betsy A. McLane’s A New History of Documentary Film (New York: Continuum, 2012), esp. 219-240, for a discussion of these distinctions, as well as their legacy.

[11] Ames, Ames. ‘Herzog, Landscape, and Documentary’, Cinema Journal 48.2, 2009, 49.

[12] Kehr, Janina. ‘Against Sick States: Ebola Protests in Austerity Spain’, Stratosphere 22 October 2014

[13] Finn, William. Elegies: A Song Cycle, Cast Recording (Varese Sarabande: 2003); Rugg, Rebecca Ann. ‘What It Used to Be: Nostalgia and the State of the Broadway Musical’, Theater 32.2, 2002, 44-55.

[14] This seeming conflation might at first seem odd or even insupportable, but it’s worth noting that, in fact, these two events are often referenced side by side, in contexts ranging from popular culture to political philosophy. For example, Marisa Acocella Marchetto’s Cancer Vixen references both AIDS and 9/11 as the context in which the protagonist is herself negotiating the possibility of death and loss in New York City, while poets like Juliana Spahr and Frank Bidart have made both AIDS and 9/11 the subjects of their individual and collective works. I think for many writers, the events resonate because both brought a sudden experience of mass casualty, followed by the relentless process of seemingly unending funeral processions through the streets of New York City; these were two large-scale traumatic events that struck the same geographical location and brought with them much larger geopolitical repercussions, not the least of which was the trauma of large-scale loss. But, the pairing of these two event goes beyond simple proximity. In her work on (and critique of) post-9/11 ethical and political theory, Bonnie Honig actually turns to AIDS aesthetics and activism as an alternative strategy to the problems with twenty-first-century aesthetics and politics and Sarah Schulman writes that ‘9/11 is the gentrification of AIDS.’ Thus, these crises are not merely two, distinct turn-of-the-century American events with a global impact; rather, they also mobilize overlapping rhetoric, as 9/11 takes up an ethics of lamentation and mourning that emerges from, but is not reducible to, the AIDS crisis. See Marchetto, Marisa Acocella. Cancer Vixen (New York: Pantheon: 2009); Spahr, Juliana. The Transformation (Berkeley: Atelos, 2007); Bidart, Frank. Stardust (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005); Honig, Bonnie. Antigone, Interrupted (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); and Schulman, Sarah. The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (Oakland: University of California Press, 2013).

[15] Jonathan Larson, Rent, Cast Recording (Verve: 1996). There’s a lot of mythology around Rent, which first appeared in 1996, particularly since its creator Jonathan Larson died on the day of its last dress rehearsal. This untimely death leant the musical a continually elegiac feeling (Anthony Rapp, who plays Mark, honored Larson at each performance by gesturing to the sky during the final stage call), despite the fact that, in terms of storyline, the production is defiantly anti-nostalgic (the show’s two leads, Mark and Roger, start off being haunted by ex-girlfriends and the rest of the musical follows their attempts to throw off the paralysis this type of nostalgia brings, alongside the fact that the show’s most enduring lyric is ‘no day but today’). At the same time, the musical is itself determinedly individualistic, in that it emphasizes the power of individual artistic creation (through the characters of Mark, Roger, Angel, Marlene and others) rather than the force of collective political action (despite its references to ACT UP, the only group session outside the central circle of friends is more a therapy or grief counseling session than the rowdy call to arms that characterized the collective action movements of the 1980s and 1990s in NYC); it is also arguably heteronormative, in that the collective queer action of ACT-UP is generally replaced by the sympathy and tolerance of the straight white men at the center of the production (see Sarah Schulman’s Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America, Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).

[17] It seems to me that Rancière and other critiques of nostalgia would argue that nostalgia in fact replaces the surprise and disruption of involuntary memory, rather than being synonymous with it; for them, nostalgia is manufactured, while involuntary memory is spontaneous. See Walter Benjamin, ‘Thesis V,’ Theses on the Philosophy of History from Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt and trans. Harry Zohn (Schocken, 1968).

[18] See Frederic Jameson’s ‘Walter Benjamin, or Nostalgia’, Salmagundi 10/11, 1969/1970, 52-68.

Stephanie Youngblood is an assistant professor of English at Tulsa Community College, where she teaches courses on American literature, composition and rhetoric. She holds a PhD in Literary Studies from the University of Wisconsin- Madison, where she was also a public humanities fellow with the public radio program To the Best of Our Knowledge. She has published articles on early and contemporary American literature, queer theory, testimony, autobiography and desire; her current project Indirect Aesthetics considers the political aesthetics of indirection across contemporary American culture.