John Paul Ricco

Félix González-Torres, Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform), 1991, Wood, light bulbs, acrylic paint and Go-Go dancer in silver lamé bathing suit, sneakers and personal listening device. © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

The Go-Go Boys were the first to go. After that, we were afraid that the rest of us would disappear too. We did. But then again, we didn’t. Not exactly. Or at least not then, or not yet.

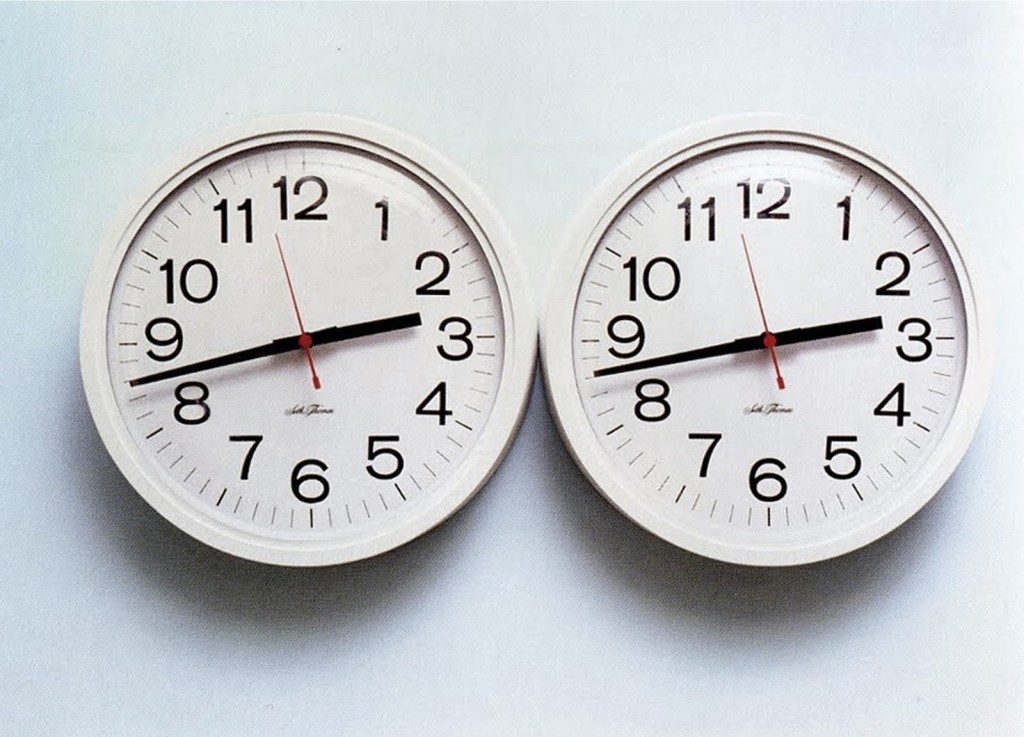

Félix González-Torres, Untitled (Perfect Lovers), 1991, Wall clocks and paint on wall. © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

The story of AIDS has been a lesson of the double.

Not of absence/presence, visibility/invisibility, or memory/forgetting, but the double of living on, of becoming-imperceptible, of forgetting that we forget. Not the unifying space of coupling, but the separated spacing of sharing in that which cannot be shared. Not the chronological time of history, but the a-temporal disjunct simultaneity of time’s temporal dilation.[1] Which is also to say: time’s irreparable disjuncture and thus its perfection. Time and the untimely timing of time. The encounter of proximity as the sense of the same time, just a little bit different. Too soon and too late, at once. Not the chronos of alterity but the kairos of the opportune moment—if not of opportunity or the opportunistic.

Chuck Ramirez, Candy Tray Series: Godiva 4 & 5, 2002, Photograph pigment ink print. Edition of 6 originally commissioned by Artpace San Antonio.

Traversing and yet other than—or irreducible to—bodies, the human, friendship, community and life. Instead, it is the ‘absolute luminescence’[2] of the empty readymade; of ‘the sex appeal of the inorganic,’[3] but also of a certain ‘disenchanted fetishism’[4] that is as much attracted as it is repulsed by the essentially ‘entropic solitude of things.’[5] A colour, a line, a knot, a last address, a hieroglyphic abstraction, glitter, rubber, a frayed edge, the impasse and its slender opening—all of these and other lures.

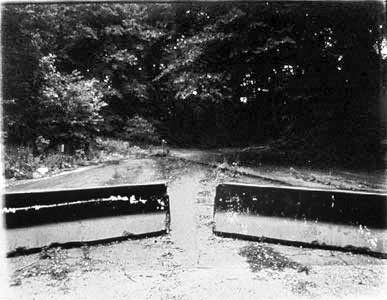

Vincent Cianni, Lake Roland Baltimore, MD, 2001, Gelatin silver print.

AIDS Doubles

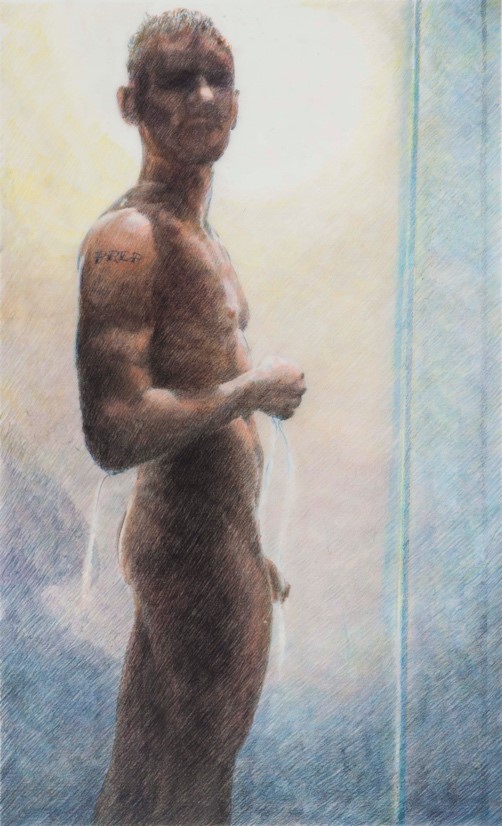

1981 Bio-Political Oblivion – 1987 ACT UP Fight Back Fight AIDS – 1988 Pictures of People with AIDS – 1996 The End of AIDS – 1996 Disappeared – 2002 SARS – 2009 H1N1 – 2014 PREP – 2016 Undetectable –

Stephen Andrews, (PREP), 2014, Watercolour pencil crayon on Mylar. Series for CATIE (Canadian Aids treatment information exchange)

‘AIDS and Memory’—that double—is the provocation to return to ‘disappeared,’ the art exhibition that I curated twenty years ago, in 1996, that was about the refusal to represent and the persistence of appearance in the midst of incalculable loss and death. 1996: when someone audaciously declared the ‘end of AIDS,’ and the time just before I read Haver’s The Body of This Death for the first time, and realized that I would forever remain beholden to—yet would never come close to doubling—the singular and uncompromising rigor of his thinking on the inconsolable perversity of existence. Meaning: what remains unimaginable and unknowable, unforgettable and un-rememberable. What queer theory remains largely unable to comprehend, and what dominant AIDS discourse will never allow.

This is about absolute memory. Absolute memory is the memory of the outside: beyond the archive, the clinic, the march, the oeuvre, the grave. We might say that absolute memory is at one with forgetting. For as Deleuze said, ‘only forgetting recovers what is folded in memory.’[6] Which also means that the forgetting of forgetting is at once the source and sense of memory, and the impossible memory (i.e. the forgetting that cannot be remembered).

![Brian Carpenter, [reenactment [infection 1], 2012, Archival Inkjet Print.](http://drainmag.com/site/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/reenactment-infection-1.jpg)

Brian Carpenter, [reenactment [infection 1], 2012, Archival Inkjet Print.

‘2016-1996’ is the double of ‘disappeared,’ and thus its own preservation of the infinity of the aesthetic task. As Ann Smock once wrote: ‘to see something disappear: again, this is an experience which cannot actually start. Nor, therefore, can it ever come to an end.’[7] In their tracing of time and its erasure, the images and scenes assembled here belong neither to memory nor to forgetting per se, but to the disappearance of the present.

‘It’s not over’ is what the double tells us.

NOTE

This essay accompanies ‘2016, 1996,’ the online exhibition of 21 works by 17 artists included in the Artist Registry of Visual AIDS. Curated by John Paul Ricco at the invitation of Ricky Varghese, editor of this special issue of Drain, the exhibition and curatorial essay respond to the journal’s theme of ‘AIDS and Memory,’ think back to an earlier historical moment in the history of AIDS when Ricco curated ‘disappeared’ (Randolph Street Gallery, Chicago, December 1996), and imagine how that earlier exhibition might be ‘doubled’ today, twenty years later.

Ricco hopes that through his brief meditation on the double, time, and disappearance, that someone reading the text will then notice the many pairings and doublings presented by the works in the exhibition, along with an equally recurring sense of the emptiness, withdrawal and erasure that punctuates the present of the everyday.

The online exhibition can be accessed at the Visual AIDS website: https://www.visualaids.org/gallery/detail/1151

[1] Haver, William. ‘The Art of Dirty Old Men: Rembrandt, Giacometti, Genet,’ Parallax, volume 11:2, 2005, 25-35.

[3] Perniola, Mario. The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic, translated by Massimo Verrdicchio, (New York: Continuum, 2004).

[6] Deleuze, Gilles. Foucault, translated by Seán Hand (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

[7] Smock, Ann. ‘Translator’s Introduction’, in Blanchot, Maurice The Space of Literature (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1982).

John Paul Ricco is a queer theorist, curator, university professor and occasional performance artist. Exhibitions that he has curated include: ‘fag-o-sites’ (with Doug Ischar), Gallery 400, University of Illinois-Chicago (1994); ‘disappeared,’ Randolph Street Gallery, Chicago (1996); ‘Love in a time of empty promises,’ and ‘Sex is so Abstract’ (a two-part video exhibition), V-Tape, Toronto (2007-08). He is the author of The Logic of the Lure (2002), which is the first published monograph in queer theory/art history; and The Decision Between Us: art and ethics in the time of scenes (2014). He teaches art history, visual culture and comparative literature, at the University of Toronto, where he is currently working on three projects: The Outside Not Beyond (the third monograph in a trilogy on ‘the intimacy of the outside’); The Collective Afterlife of Things (a book-length essay on art and posthumous humanity); and Sex, Ethics and Publics (a collaborative research working group, that he is convening in Toronto).