Alexandra Juhasz (in conversation with Jih-Fei Cheng and Lucas Hilderbrand, and Adam Geary, Theodore Kerr, Nishant Shahani, Dagmawi Woubshet, and others)[1]

Queer time and place register and change in media and conversation about HIV and the bodies and domiciles that house them. In some times and certain places, we might sense this as political. Of course, over time and place and medium that can change. Writing as an AIDS activist scholar and videomaker, reflecting upon a series of projects and conversations that have represented the dailiness of HIV across many decades, I am also thinking about the changing contours of AIDS activism and the increasing depoliticization of (the video of) the domestic. I will argue that while being HIV+ (or negative) has always engendered daily practices that are lived out in the bodies and homes of PWAs (People with AIDS) and their communities (and sometimes also out onto the streets), as the politics of AIDS and video change, we find there are multiple and even conflicting practices of videotaping our comfort or distress with sero-status and (ill) health and the associated ordinary, routine activities that might require representation and action.

Lyle Ashton Harris, still from Selections from the Ektachrome Archives 1986-1996, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Visual AIDS.

While some representations of HIV-affected bodies engaging in the mundane are directly linked to activism,[2] others suppress, unmake, domesticate or depoliticize this possibility. These multiple senses of and uses for images, across the duration of the AIDS crisis and within the representational uses of bodies and HIV at home, engender a rumination on queer time/place, as do reflections upon my own bodily enactments in the face of HIV, particularly in regard to what I will think through here as the artists’ and critics’ role in the production of forms of politicized conversation. Since I have written and made media about AIDS across its long, disastrous history, and I reflect upon my own past and present here, this piece also enacts and reflects upon the focus of many of my scholarly peers: namely the place of time, loss, media and AIDS in a contemporary ‘queer retrosexuality,’[3] how the ‘rhythms of our loss have changed.’[4] Thus, I begin in the/my past, albeit, I hope, without the nostalgia that taints so much queer retrosexuality. I move through my own early activist AIDS video, and those of my peers, and then into the ongoing life of these self-same videos in archives today, to then look at two more recent iterations of AIDS video to ask: how, where, when and for whom is ‘being at home with HIV’ (and video) sensed as political? Critical here is the caveat and video; it is a different question entirely, and an interesting one, that considers when being at home itself, outside of representation, is in its everyday doing, political.

I will however ask here how, or perhaps for whom, over the changing history of AIDS representation and its recorded lived experiences, has this activity and its image become almost entirely domesticated, in the sense of tamed or housebroken? To do this, I will also look at more current representations of HIV and home as seen in Alternate Endings, a body of seven art videos commissione by Visual AIDS in 2014 for the twenty-fifth anniversary of Day With(out) Art.[5] I will quote extensively from a conversation about these videos[6] between two younger scholar/activists, Jih-Fei Cheng and Lucas Hildebrand and myself, held on 1 December 2014 at Los Angeles’s MOCA. I will then look at several recent feature-length documentaries (primarily from 2014 and 2015) that, while not all explicitly ‘AIDS documentaries,’ do figure HIV/AIDS as part of a larger set of queer concerns or histories.[7] In these two modes of contemporary fare (art video and made-for-broadcast documentary), we find home to be a place of isolation, comfort, self-care, atomization and medicalization. However, conversations about these representations are another matter, as we shall soon see.

The AIDS Activist Media Archive of the Ever-Empowered Disenfranchised

In 1990, WAVE (the Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise), a collaborative of women thinking about and making AIDS activist video, produced and then distributed We Care: A Video for Care Providers of People Affected by AIDS. The project was funded primarily by the New York Council for the Humanities and community-based AIDS service organizations, including our sponsoring organization, the Brooklyn AIDS Task Force, and it was also my doctoral research, which was intent upon theorizing and making community-based, community-specific AIDS educational materials as anti-racist feminist activism. The WAVE collective was comprised of myself, a white female video AIDS activist and graduate student, and six black and Latina women. Together we were poor, working-class and professional female AIDS activists who sought shared empowerment in the face of personal, familial and local devastation.[8] The video we made is comprised of several ‘chapters’ devoted to what a person newly coming to the caretaking of a PWA would most need to know (about services, preparing for death and dying, relieving stress, how to be a volunteer), and was pitched to an audience of urban women and people of color. Each informative sequence was made by the group as a whole or a subsection of it. At its heart is a powerful piece of almost uncut video that comprises the chapter ‘Being at Home with HIV.’

I shot the sequence with a consumer VHS camcorder and was joined behind it by Sharon Penceal, another member of WAVE. In front of the camera, giving the two of us and our anticipated audience a tour of her home, stood Marie, a person I understood to be a dear friend of Sharon’s at the time, but whom I later learned to be Sharon’s lover. In the tape, we start in her living room where she explains that ‘she needs a new carpet, but that’s another story,’ and we move steadily across the apartment to kitchen, bathroom and bedroom, Marie mixing honest descriptions of how she keeps herself and family members safe and healthy with a disarming mix of self-deprecating humor and a steadfast personal agency: ‘there’s only one bed in here, which means people can be safe sleeping with me … depending upon what they intend to do with me.’ When we shot the video, Marie was a robust, poised, middle-aged black woman living in a one-bedroom apartment in the Rockaways with her granddaughter and sometimes her son (and Sharon?). She had been HIV-positive for several years, was taking AZT, and enjoyed good health. She was also one of a small number of black women who agreed to be videotaped, at home or anywhere, as an out PWA. This was a bold political act in 1990 when PWAs were unprotected by anti-discrimination laws, and very few women were out with their HIV; it continues to be a political act because women and trans-women, children, the elderly and people of color—in relation to HIV-status particularly—suffer stigma and related oppression.[9]

Over the great many years that followed—which were tarred by Marie’s death soon after we visited to capture her daily experience on video, as well as the deaths of all of the other PWAs who were being cared for by members of this group while we were making the video in 1990, including my best friend, James Robert Lamb in 1993—I almost always chose this chapter to share when screening the tape. I wrote extensively about what this sequence meant to me at the time, or more precisely a few years after we shot it, as part of my 1995 monograph AIDS TV: Identity, Community and Alternative Video.[10] I wrote my dissertation, from whence the monograph came, about the first decade of AIDS activist video in 1991, soon after Marie and so many others had died despite our active, passionate, shared attempts to save them and others. For the book, only a few years later, perhaps awkwardly but always desperately, I theorized, as we all did then, about the crisis and its meanings in real-time, so as to feed the movement and try to heal myself. Like our video of this dreadful era, I understood this writing as a political act: turning my daily experiences of AIDS as a scholar and activist into recorded, sharable, usable material. I wrote my ‘scholarly’ book imagining the women of WAVE, and similar communities of activists, as my primary readers.

Now, preparing for this essay, I can’t help but consider how my own past practices are recently and poignantly described by Dagmawi Woubshet, who distinguishes the temporalities of our early prose from current AIDS writing because the rhythms and functions of our loss change across the decades. As I write now, I find that ‘Being at Home with HIV’ has come to mean both the same, and also much else over the many years that have ensued. It always moves me and audiences (I interpolate) because of Marie’s warm, funny and astute performance; because of the level of comfort she exudes with the camera and its anticipated spectators, this feeling so rarely captured in the representation of working-class people of color and/in their homes;[11] and because it feels so ‘real’ in its DIY VHS grittiness, its hardly cut-ness, its unrehearsedness and its unstaged naturalness of place, demeanor and vernacular. However, at a dinner with fellow AIDS activist panelists after a recent screening within a larger panel, several in the group referred off-handedly to the clip as ‘poverty porn.’ Its changing interpretation has stuck with me. First, because part of the power in Marie’s performance, in my loyal reading, comes from her visible and felt pride about her home. She was decidedly not-poor, but rather, working class. And second, because my colleagues’ contemporary reading attests to how viewing practices and norms change, even as media stays fixed.[12] These younger AIDS activist viewers placed the footage into a recognizable nomenclature of the present, that of something-porn, whereby something private or specific to a local community gets seen way-too-much for the pleasure of an insatiable public who themselves have already seen too-much of that local x, but somehow still need even more. The raced, classed, gendered and even aged nuances of Marie’s performance of self and domicile, so visible to me in their understatement, so political in their original time and place, are now shrouded by a set of social cues and media practices that have come to mean ‘over-sharing’ and also ‘anti-political’ in this present time.

Thus, as cultural markers and practices of race-class-gender and affect shift, as they inevitably must, the clip has become newly moving and meaningful. It is now a piece of memorial media to lost people and practices.[13] ‘Being at Home with HIV’ is a testament to the death of Marie, and so many like her. As critically, it marks a moment of activist video possibility that comfortably linked being at home and video with an overt and implicit set of formal, aesthetic and on-the-ground politics. That is, to be home and out and proud on videotape was visible as something political at this time for reasons that are no longer current. At the time, there were very few images of black, middle-aged women with HIV. So, in its original time of production and reception, a politics of visibility was key. But furthermore, during this time, there was an organized (media) movement to which this set of images of the home tour, and the larger video itself, connected. We made Marie’s tour of her home in dialogue with a linked social movement and political demands that had been generated through conversations about the daily experience of domesticity in proximity to HIV. At that time a politics of the personal of AIDS was active.

Marcia, Glenda, Juanita and Alex. Still from WE CARE: A Video for Care Providers of People Affected by AIDS, Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise, 1990. Courtesy the collective.

At the onset of the AIDS crisis and its linked movements for social justice, video activists understood that we were participating in (and building) the first truly postmodern media movement. We used newly available sets of technologies to self-document and share our lives, ideas and movements, to make our own educational and cultural materials, to speak to and against the ‘mainstream’ media and culture, and to work to alter material reality through carefully enacted and theorized acts of representation.[14] We explicitly made ‘AIDS activist video’: media made in conversation with movements, actions and people actively contributing to change. There were other forms of AIDS media: mainstream documentaries, network journalism, tawdry bio-pics, educational industrials and a few well-intentioned, yet sentimental movies that we activist/scholars angrily and compulsively read against their grains. (Interestingly, as the years of the epidemic have mounted, as we critics have aged, and as AIDS has changed, many of us have returned to these same films to re-evaluate them for the present.)[15] Then in the decades that followed, there was profoundly less coverage of the crisis by activists or otherwise, and we entered what AIDS activist and theorist, Theodore Kerr calls the ‘Second Silence.’

We’re in a new period now, according to Kerr, one of ‘AIDS Crisis Revisitation,’ and I write today as part of that: an AIDS activist videomaker who collaborated on We Care and many other works that contributed to my community’s feminist, anti-racist, queer voicing of of a particular form of AIDS activist politics and video. I was, and still am, part of a community that is deeply committed to an ongoing, powerful and intense strain of AIDS (media) activism and academic inquiry that Cathy Cohen, a scholar and contemporary of mine from ACT UP, describes as the ‘principled transformative coalition work.’ In quoting Cohen’s earlier work now as he reconsiders the early AIDS activist work of queer people of color, Jih-Fei Cheng holds on to these transformative possibilities for what ‘queer organizing offers.’[16] This coalitional strain of AIDS (media) activism (and criticism) has always been as powerful as it is marginal: as inspirational and smart as it is intersectional. We speak to and against dominant media as well as other traditions of activist media. Just so, the names of the conversants who I list in my title are contemporary scholar/activists working in, learning from, and modifying this tradition for our present. We all ask a version of a decades-long question: what does an AIDS (media) activism that forefronts the voices and experiences of the communities who are hardest hit by HIV/AIDS and yet always also the least-seen look like: women, people of color, trans-women, children, people of the global south and poor people? And we testify, through our work, that just because we are less-seen doesn’t mean that we aren’t or haven’t been seen, that we don’t show ourselves, and that we aren’t always fierce and often at the table making demands and working towards a better future.

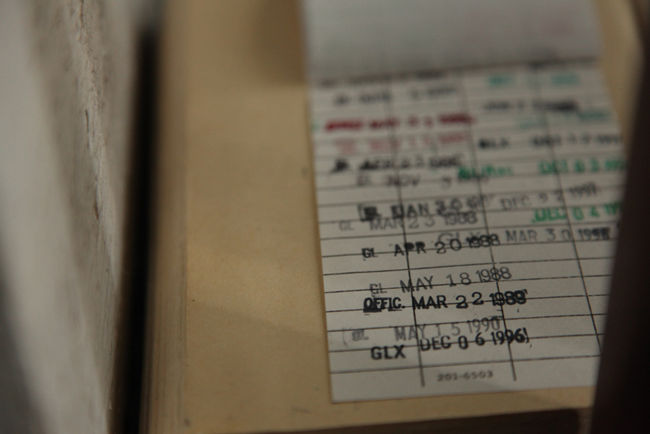

In the early years of this activist project, we made boatloads of media demonstrating these very tenets, newly empowered as we were by the camcorder and other technologies. Our obsessive AIDS media practices,[17] bent upon representing and understanding HIV/AIDS on our terms, would anticipate, model and fuel much of what has become our contemporary social and political media culture where nearly everyone self-represents. As a result, we have also enjoyed the unanticipated fruits of our rich and diverse self-produced archive of video records of our own daily practices, outrageous actions and acute analyses from the earliest years of the crisis. With hindsight we learn that, in fact, successful postmodern media politics demand not only thoughtful, political practices of self-representation, but also self-archiving—a set of linked activities that in previous writing I have called ‘queer archive activism.’[18] Many of us first-generation AIDS video activists (those of us who lived and stayed connected to the movement) participate in this present-day archival activism by conscientiously securing our media records for future use, reusing them to further our current goals, and sharing them with others.[19] The result has been the production of archives as well as new media—albeit largely about the past—and in the nostalgic mode. This recent body of work has been well attended to by myself and others;[20] we consider the consequences of the large number of backward looking documentaries about the early history of AIDS (activism). But given the pace of today’s media culture, this body of work from approximately 2010-2014 has already produced media responses in the kinds of work I discuss later in this article, as well as the activist challenges that are at the core of my thinking about political conversation.

In its first instantiations of return, the most commonly revisited views of our archives proved to be scenes of ACT UP street activism and other images of the experiences of gay white men who were decimated in the early years of the AIDS crisis. While pleased to see AIDS emerging from its long representational slumber, many of us have felt compelled to distill the consequences of what Nishant Shahani has named a ‘historical whitewashing,’[21] since by definition, ACT UP footage most often focused upon the white gay men who were the majority of the group,[22] as well as the tactics of street activism that were interesting and available to only some AIDS activists.[23] As is true now, was true then. Gay white men suffer from HIV/AIDS and related oppressions of homophobia and stigma. Their cruel and disenabling experiences of the crisis are a critical, central reflection of the North American encounter with the virus. Of course, gay white men’s access to cultural and monetary resources have meant for many of them a rather unique trajectory as well, when compared to other at-risk communities within the lengthy and changing history of AIDS: one of (relatively) heightened access to means, including media, medication and money. Needless to say, this group is as diverse and multiple as any: many gay white men are poor or have been impoverished through their HIV (I will discuss this later in relation to the film Desert Migration), our gay white male colleagues have been radicalized by our movement and have helped to radicalize it (as is reflected by the many gay white men who I learn from and converse with in this essay), and each man brings his own history of personal power, loss and oppression to the table. Regardless of their diversity as distinct humans, however, Cheng (and others) attests that there are consequences to over-visibility in these films: ‘the “liveness” of white men on film foregrounds them as the historical actors of the crisis while women and people of color are relegated to the background or exist off-screen as the passive and fated recipients of the historical “burden” of AIDS.’[24]

But, our strand of AIDS activist media politics has always worked against one set of images standing in for the entire story of AIDS. We know that the crisis occurs differentially across its multiple communities and locations, and that the core of our politics is that we want this to be seen and accounted for. Geary writes: ‘talking about gay [white] men and other queers (homophobicly) has been a way of NOT talking about the structured inequality and violence that have made some bodies susceptible to viral infection.’[25] In this vein, I too, as a white, queer woman, have argued that the many recent media returns to white gay male suffering and activism foreclose remembering all the others who were in ACT UP, and elsewhere, across the diverse and robust AIDS activist landscape.[26]

Beyond its whitewashing and myopia, the backward look of most contemporary AIDS media also shuts out possibilities to see what HIV/AIDS (activism) looks like in the present, contributing, albeit usually perhaps unintentionally, to a neoliberal post-AIDS mindset and politics—the focus of the part of this essay on recent film-festival documentaries. Contemporary documentaries look back because ours is now supposedly an ‘AIDS-free generation’ brought into being by bio-medical and technical interventions and preventions. There is no AIDS to be seen and hence no need for AIDS activism. Bishnu Ghosh illuminates the stakes of this visual logic in our recent conversation in Jump Cut: ‘one of the consequences of the “pharmacological turn” has been an intensified focus on biomedical interventions as the frontier in the struggle against AIDS…the fight, now waged on a global scale, continues: AIDS media activism unrelentingly intervenes in public policy, drug legislation, and prophylactic measures attempting to ameliorate the quotidian struggles of living with AIDS.’[27] Contemporary AIDS activists draw out the chilling terms that past and present silences play in today’s quotidian struggles. Kenyon Farrow writes:

In a country where health insurance is largely employer-based, high rates of unemployment among black men as a whole increase health disparities that promote risk of HIV, such as higher rates of untreated sexually transmitted infections that can help facilitate HIV acquisition. Thanks to their lower level of contact with the health-care system, black men are more likely to be get tested for HIV only when already in advanced disease, so an HIV-positive test often accompanies a diagnosis of AIDS. … Being part of the ‘AIDS-Free’ Generation Hillary Clinton announced in June should be every black gay young man’s right. Yet we have everything but the political will to make that a reality.[28]

For AIDS activist videomakers, this means what is always has: we need to make, (re)visit, show and interpret the many ways that AIDS is lived, day to day, in America and around the world. Media that functions to ‘provincializ[e] the U.S. as uniformly western, rich, and advanced, rather than fractured by racialized inequality and social violence,’[29] produces safe, domesticated AIDS subjects and politics. What does that look like; what are the forms and aesthetics of this housebreaking?

Being at Home with HIV: Conversations about Alternative Endings and Activism

By late 2014, artists and activists engaging with HIV/AIDS were responding to both the past of AIDS and the contemporary documentaries (about that past) that were suddenly in rather large circulation. Working within what I have now repeatedly called ‘Internet time,’ what Ghosh sees as the ‘changes of scale and temporality that the digital brings to HIV/AIDS representation’[30]—whereby some images can move quickly, deeply, and virally only then to be as quickly emptied out of poignancy because their over-saturation drains them of signifying power[31]—the Alternative Endings videos display a responsive visual lexicon that speaks to or perhaps against the first round of return, simplified as an AIDS of gay white men protesting on the street and suffering in hospital beds. The Day With(out) Art videos still have (for the most part) a backward gaze, but this yearning has found at least one new locus: the home, the home movie, the everyday.

In large part a reflection of the political investments of the programmers (themselves working within the long activist tradition I have been naming here), the seven works commissioned—made by women and men, trans- and cis-gendered people, people of color and whites, and members of several AIDS ‘generations’—look little like the feature-length documentaries that had begun the Revisitation. Of course, they are shorts and ‘art video,’ and these subsets of AIDS media move to different audiences and towards other ends than do feature documentaries. But even so I noted, in conversation with Cheng and Hildebrand after the screening, that as scholars of AIDS activist media, we could still find much to-be-expected in this new video work; we could see many of the old standards or stand-bys of AIDS activist video. Together we named and discussed these similarities and differences.

Panel and audience, MOCA discussion, Alternate endings, 2014.

Panel and audience, MOCA discussion, Alternate endings, 2014.

What follows are two lengthy excerpts of that conversation, slightly edited with my fellow conversants’ blessings. I think this demonstrates, in form, how AIDS activist knowledge—the language we need so as to be equipped to see, critique, and make AIDS cultural politics—is built in conversation with others, and contemporaneously with the art work and activism that surrounds us. The role of AIDS activist theory will also be the subject of my conclusion, where I will consider how conversation may serve as one form for the queer of color, feminist, anti-imperialist quotidian collaborative activist practice that many of us crave, value, and can still make together:

Alexandra Juhasz: I have produced a set of key words that I think are helpful for us to frame our conversation. And I have a secret one that I am going to use to stump the panel.

The first is ‘Generation,’ a word consistently used to frame conversation and thinking and activism and lack of activism and new activism around HIV/AIDS.

‘Nostalgia’: one of many possible affective states being deployed in these tapes. We might want to think of that range itself as a generational problem—or a generational solution.

‘Mourning’ is always key and also complicated around the question of generation as I look out across this room today. This room is really beautiful to me because I can’t decide why you all are here, what ‘generation’ you are from? Some of us, from my generation—I am 50 years old this year, I was in ACT UP in New York and lost friends at that earliest moment of AIDS and its activism—we often come out to mourn the people we lost. That is part of what we should do at these events. But many of you in the room haven’t lost people to AIDS and didn’t and don’t experience HIV/AIDS as a mourning project. And while I know you are respectful of our mourning, and I appreciate that, I also know it can’t be the only project in the room, even if it needs to always have space.

We see many Queer People of Color in these videos (and in the room) but I would like to change the key term to ‘Disidentification’ in honor of José Muñoz and the My Barbarian piece that commemorates him and his work.

We are also going to talk about ‘Videotape,’ something that the three of us study seriously in relationship to HIV. I think a lot of the pieces are working through disidentification to ‘popular culture.’

Jih-Fei and Lucas would you like to start with ‘Generation’?

Jih-Fei Cheng: Sure, I will say a little bit about my background so folks can determine what stage/what generation they think I am at. I came to a queer world, a gay world—whatever you want to call it—through HIV/AIDS. Not only was it in the general public’s conscious by the time I was in junior high and high school, but the first person I was with in 1995 told me he was HIV-positive. And when I began college, AIDS was often talked about. But we encountered the discussions with feminist and queer theory. We watched films in class like Silverlake Life. So AIDS was very much part of my coming of age story—if you want to call it that—of being gay or queer.

When I finished college, it made sense to work in HIV/AIDS social services. Part of it was because, at the time, as a young person of color in a gay community that felt largely affluent and white and male, there were outreach workers that were targeting men of color, young women and transpeople of color, with HIV prevention messages, and that was how I got brought into the world of HIV/AIDS social service work.

I was continuing my work in AIDS in LA and NY in a different form, and I guess one thing I want to say is that the ‘generation’ line blurs for me. I was not present (in AIDS activism) during what is considered ‘the crisis,’ but for me, it has been a protracted crisis. When people were supposed to be living, my friends were dying. A lot of my lovers have been HIV+ or have become sick, and I wear that on my sleeve and in my heart in all the work I do. To be gay or queer, and of color, and to also think about AIDS in the moment that I came of age is something I cannot disassemble.

Lucas Hilderbrand: The conversation about generation and AIDS is one that I have had many times over the years. I am a year older than Jih-Fei, but I came of age when being gay meant being HIV+. There was a cultural conflation of the two, so for me growing up in a small town in the Midwest, remote from cities and gay communities, my understanding of queerness and queer life was very much bound up in the AIDS crisis. For me queerness existed in cities and through HIV/AIDS. I had a political identification with AIDS before I had a community or a sexual life. I have had many positive people in my life in various capacities, but I have never lost someone to HIV/AIDS. I have a very complicated relationship with it. I have this identification, and yet haven’t felt a deep personal loss the way many other people have. It is curious to be between generations. My relationship with AIDS is in many ways mediated by representations on TV, film, media, writing.

AJ: In fact we met when you were reading—in a way that I ultimately sort of called you out on as being ‘incorrect’—the ACT UP floor from its video representations.

LH: It was actually an instructive conversation. I was reading a video by James Wentzy that was a 15-year anniversary documentation of ACT UP at that point [Fight Back, Fight AIDS: 15 Years of ACT UP, 2002], and you and I had very different perspectives on what that footage meant. I think it was probably helpful for both of us to have a lot of tension around what that means.

AJ: At that time I was calling you on your nostalgia for something you had never experienced, which was the joy, the play, the community…

LH: …the vitality, the activism…

AJ: …the desire, the anger which you thought you saw on the floor of ACT UP, but that you had not experienced. So your nostalgia, in that sense, ‘was killing me.’

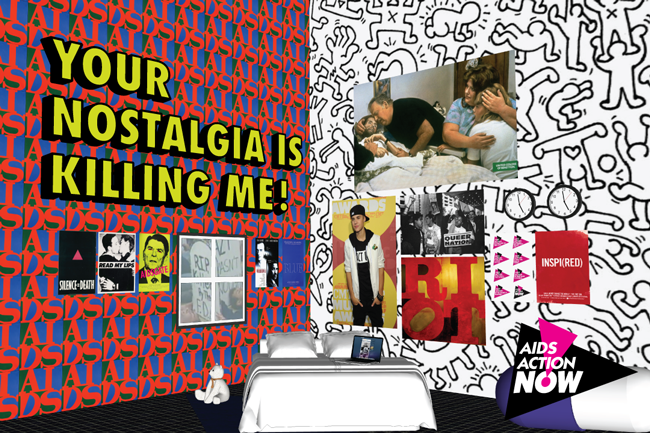

I don’t know if you all know about the deployment of the phrase Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me. But it has come up recently in segments of the HIV/AIDS community responding differently to how people in my generation are producing quite noticeable documentaries about AIDS activism in the 80s. Younger people in the HIV/AIDS community have said: ‘enough, okay. We honor your memory, we honor your pain, but there are other conversations to be had.’

But your nostalgia around the reading of James’ tape was killing me because I was like, ‘dude don’t be nostalgic, everyone was dying.’ I think this question about placing affect on a videotape may be a good place to start, so let’s look at this generationally.

LH: I just want to say something about what else I have learned now that I am the old person in the room when I teach: most of my students have no relationship to the AIDS crisis. And so when I teach AIDS, it is always an interesting experience. For undergrads, there is not always a cultural knowledge of the history of AIDS as being a gay disease, as incurable, or that there is a history of activism. There is a shocking lack of cultural memory, on one hand, that I try to tease out, and at the same time, I am never sure how they are reading these texts either. The compounding of generations becomes really complicated.

AJ: I watch Ashes, by Tom Kalin—who lived in my apartment, with whom I was an AIDS activist and art-student—and everyone he names in the piece, in his litany of loss, is someone I knew. And so that is a piece of mourning work for us. But that is also a piece of art on a wall that is then received by people, even in my generation, in other ways. So I think the project of how we speak across this long expanse, this long duree of AIDS, these multiple generations, begs the question: can we rightfully own our own AIDS experience while being open to others? It is very hard to do. There is a lot of looking back in these works. Only Glen Fogel’s 7 Years Later does not look back, right?

Tom Kalin, still from Ashes, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Visual AIDS.

LH: But it is after a break up.

AJ: It doesn’t look back at that ‘definitive moment’ of AIDS crisis activism. It places its story in our time now, this time, although the two lovers are discussing their own, personal and historic AIDS crisis (when one lover tells the other he is HIV+). But again, generationally, Rhys Ernst’s, My Barbarian’s and Hi Tiger’s pieces are by younger artists that are—nevertheless—reaching back into the archive to find remnants that allow them to chew on that definitive moment they did not experience.

JFC: This goes back to the generational thing. When I look at your work, Alex, I am reaching into that particular past—not just the video work but also AIDS TV—and I look to find answers about the present from that past, from the moment you were writing within the academy but also your life before. When I met you I realized we have a shared sensibility—an affinity that seems to cross a generational divide—that, for me, is about missing images. It is about the missing images of people of color in what is now constituted as the gay world, and the oversaturation of certain kinds of images of people of color that are seen when it comes to HIV, and HIV prevention. When I see current documentaries about the AIDS activist past that are popular, they are not jibing with what I have been told and what I experienced. When I met you I felt that what brought us into the same room was this question of what happened to these missing images? Some of them were of people who have passed, and are not represented, or their lives are not represented in ways that you remember them.

AJ: So how does Lyle Ashton Harris’s piece function for you in regard to your search for missing images of queer people of color because in his work we find his private images of community, love and loss?

JFC: Some of those people I had seen in images, and some not; so I wasn’t immediately connecting all the people with the works that I have read or seen. I had to go back and look. In a way it felt like something was really vibrant that is still here. I saw the generational divide in the aesthetics of the image. But I also saw how, in the contemporary moment, people want to look like that again, to dress like that again. I felt like there was something not so distant about that past. That past is surfacing again in popular culture. Yet, more importantly, I also see queer people of color still engaging in work that resonates with or continues that (past) moment.

LH: One of the things that struck me, particularly watching the program again today is that time, in each of them, is non-linear and seems very personal. I am struck by how Tom Kalin’s piece is very personal to his own experience of the people he lost. Some of the names and dates I recognize, and some I do not. His mourning becomes very personal—a personal experience of a crisis and a timeline. But then in the piece by Hi Tiger, they are performing a New Order song, which speaks to the ways in which there are idiosyncratic texts that people seek out or that resonate that are also personal.

Hi Tiger, still from The Village, 2014. Courtesy of Derek Jackson and Visual AIDS.

AJ: Let me end this conversation with my secret word: ‘Activism.’ I think it is interesting for two reasons. The large group of very visible and very beautiful and important documentaries that have been made in the last four or five years—one of which has even been nominated for an Academy Award (How to Survive A Plague)—are largely about ACT UP activism. But there is no activism in any of these tapes, at least in the sense of images of and reflections upon collective direct action in the streets, ACT UP activism, but rather, as you just said Lucas, a personal sense of time and a personal sense of HIV/AIDS. There is an AIDS history but deplete of activism (and also of overt images of sex and sexuality, by the way). These absences are quite stunning, actually. I wonder if you noticed, and if you guys want to talk about how that makes you feel, thinking about the twenty-five years being commemorated tonight.

LH: My gut instinct is that—at least about the work I largely know—AIDS has been defined by activism in a lot of video work. So, maybe there is an activism exhaustion, a trying to do something different.

An activism exhaustion, a sex exhaustion? After this event, I continued to think about these questions and talk to my friends and colleagues about them. Ryan Conrad informed me that when he teaches a course on AIDS media, his AIDS-savvy students roll their eyes at over-used images of ACT UP street protest which they’ve literally seen before: activism-porn[32] … Tom Kalin, Theodore Kerr and I started chatting about these questions on Facebook and moved the conversation to a phone call. From them I learned that at the New York screening of Alternative Endings, the artists in attendance had expressed that they do not make ‘activist art,’ but rather ‘political’ art and/or or art that happens to sit in a space that others might have once thought of as ‘activist’ because it is about and by gay people. I told them that I worry that the contemporary (art) video work, and the community’s voices that name such work as ‘activist,’ seem curiously or perhaps counter-intuitively detached and privatized. I wonder how today’s radical conjoining of media, telecommunications, computers and corporations affect our sense and practices of the political, of activism or direct action, and what these look like?

In Alternative Endings, most of the videos represent individuals at home, from there linking to history through computers and phones and the many archives readily found online (often because our activist interventions got them there). But none of these videos make the formal, aesthetic or political move to connect their seeking subjects to a movement or a linked set of people or political actions or demands (although Kalin’s piece does connect to a litany of past actions). This new image of activism was one atomized in rooms; privatized at home in the bedrooms, garages, BBQs and iPhones of American queers (Tolentino’s piece happens as a performance in a private dance studio). Neoliberalism’s self-care, enacted in these videos through practices of leisure, lifestyle, research and consumption, may be (self) healing, but also seems to disconnect the people in the videos from public and counterpublic spaces. Meanwhile, in We Care, when Marie performs herself for the camera, for our community and anticipated audiences, her activist actions and articulations are overt, if still homebound: naming local and systematic oppressions as she shows us her bed and bedroom by acknowledging the politics of her sexuality; naming modes of keeping her family together as she explains how she cleans her bathroom; and linking herself and her household to the active community of activist/artists who made the videotape, via editing as well as a palpable spirit of collaboration and community conversation, so that the tour of her residence is only one chapter within a larger argument, thereby suturing images of her private dwelling to the tape’s overtly activist orientation towards self-health, self-help, and self- and community-empowerment.

Julie Tolentino and Abigail Severance, still from evidence, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Visual AIDS.

At the MOCA event, I suggested that the tapes seemed to mark a cultural zeitgeist where the making of images and the moving of discourse are in and of themselves understood as political, as activism. We opened up to the floor at this point in the conversation to discuss these issues with the large audience in attendance. There was huge pushback. We went on to productively and collectively converse about and debate what counted as AIDS cultural activism in our time:

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Activism is always a personal thing. Do you see activism as being about action?

AJ: Yes, my definition of activism is action-oriented. Period. End stop. That is not to say I don’t value things that people do at home, but I would not call that activism. I would call it something else: reading, typing, liking, sharing, posting. That is not activism.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Are these valid things?

AJ: Of course they are valid things, but not activism. Valid. Productive. Hey, I like, I post, I text, I do those things. I live now, in 2014. But I don’t call that activism. I do call it proto-activism.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I think there is something interesting about the lack of activism in the work in that there was a special moment, and that there is something not relevant about activism today, or it is different now than it was in the 80s. Maybe the absence is about the questions of relevance in relation to the work.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I caution us in how we are talking about activism. There are people who are in NY that are blocking bridges and Acting Up right now, and there is the ever-present Occupy movement. People are not dying, and the motivation is different, but it is dangerous for us to throw the idea of activism under the bus. It is not to say that I don’t dislike slacktivism.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: There is a difference. I worked at an AIDS organization. I watched 50 friends die. Part of what is different now is that our fight, our activism back then was focused on the gay and lesbian community, we did not have the time or space to focus beyond that. We talked about race, gender, during the AIDS crisis, we were so plugged in. And now there are so many things—I was talking to my gay white friends—they are shooting black men right now, but what are you going to do when they come for you? AIDS was our plague, and now we are looking at a class war that the younger generation is dealing with that I don’t have the energy for. Part of the online world we are living in is distracting us.

JFC: When I showed the Testing the Limits Collective’s 1992 Voices from the Front to my students, they were really taken aback that the AIDS movement even happened, that there was AIDS activism, that there was a lot of direct action. One student piped up and she said, ‘it is so interesting to watch them be so angry.’ Another student said, ‘yeah, they are so violent.’ And then it was my turn to be taken aback. I was thinking: ‘they are literally showing you how they trained in non-violent action and you are calling them violent.’ I think what is missing in the discussion is how public space has radically changed because of intensified police tactics and a change in mainstream media that is so starkly different now than the moment of the AIDS crisis, which AIDS media was attempting to correct.

In 2004, when I was in New York and we were protesting the war, the streets were filled, and there were lots of police. It was a global action but it barely got any mainstream media attention. I think we are in a moment where one of the reasons we see a lot of AIDS activist videos resurface and being repurposed—and I learned this from your work, Alex—is because the AIDS activist movement was the first movement to adopt handheld video cameras to use during direct protest. The AIDS activist movement is a model. Now, we are seeing students, and young people (and not just young people) in protest, on bridges, in Ferguson, videoing things and sending them to each other. And you have people in Palestine sharing things with people in Ferguson.

I think activism is changing because of the changes in media and in public space, but there is not a loss of possibility. The images are doing a different sort of work. People are using media to find alternative modes of assembly when public space is being clamped down on. These uses of media do not replace the congregation of people in a physical, public space; they lead people to that public space.

AJ: I really like that: the images are doing different kinds of work. I would like that idea to hold, and for people to think about how images are doing work now and here, and how we need different kinds of image-work given the overproduction of images, the over-glut of images.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Are you insisting that activism has to be out on the street?

AJ: I am not insisting on anything. I know it is being taken as that.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Are you saying it has to be out in public?

AJ: I was interested in the word ‘action.’ We could have a long debate, and I hope we don’t right now, about what kind of actions count. Of course it is action.

The other thing that is important is the word ‘movements,’ right? What does it mean to share material now that it is so easy to share, when there is so much? When we were making video in an earlier moment and images were doing different things, we had to share them within a much more coherent movement. There was a gay and lesbian coherence, a kind of finite quality of the audience and circulation of material that allowed it to grow and build with coherence and complexity. It is much harder for us to gain that now, to make movements, to make arguments because there is so much imagery.

Coherence matters so much. So I really appreciate your point around clarity. Coherence is much harder in this postmodern, web 2.0 moment where there are too many images and so much multiplicity of meaning. I think it is hard to lock down and make movement with our actions and/or images. How are they consolidating is a question to me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Activism is shutting down bridges but also it is making other performances.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I am trying to search in these films for other detectable alternative endings, other approaches to activism, which is not just putting on stiletto heels and putting on a very hetero-normative song by New Order. Isn’t allowing us to watch, from multiple perspectives, the two men sitting at a kitchen table a kind of queering of activism? It is not just action, text or words. There are many different ways of representing activism.

JFC: Alex, I don’t think that your concern is that these images are not doing anything. I think your concern is that people are invested only in the image.

AJ: Being in this room together watching these art videos is a form of activism. We engaged in the action of getting here; we are having this conversation. This is activism. It would be more exciting for me if we also now named something that we were going to change and then worked together to do it but we probably can’t do that in this space. Yeah those are all forms of activism. So let’s not just get stuck in defining it as one thing. What is interesting to me here is that the videotape register has been pretty fixated on my generation on the street performing the first acts of postmodern activism. Producing signs, producing spectacle, figuring out how to manage the news. And those much-seen videotape images are not here. That is what I am saying. Maybe those images are now dead to us, tired, used up. We need new images. We have chewed them up.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Mass media is over. The Grindr chats in Ernst’s piece are activism. They are interaction, getting to see person-to-person what the other says.

LH: If we look at the My Barbarian piece, which is drawing from José’s work reading Pedro Zamora in The Real World, it is an activist intervention with ‘counterpublicity’ creating queer of color spaces to counter the dominate media. They cite a piece where José is doing a different model of activism. Some of these pieces, which are by younger generations, are rehearsing different things—whether it’s re-performing The Real World, or revisiting or rediscovering Lou Sullivan on YouTube, or Hi Tiger’s re-staging with difference—to rework the history, which I think is activist.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: We are in a period in the art world where the lifestyle is the work of art, a practice; a lot of these contemporary artists see that as success, influence.

LH: So in a way your initial question about where is the activism is a curatorial question. You had a conversation with one of the curators of the show and his response was that it was the personal vision of the curators, Tom Kalin, Theodore Kerr and Nelson Santos. Do you know what ‘Alternate Endings’ means or where they are going with that?

AJ: No. But one of the craziest of endings is that people lived and they are making art. Who knew that that was the alternate ending? Activism out of people living is different than activism out of people dying.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: There seems to be an intervening rod called commerce. These artists are working within institutions. The activists were initially creating work working against them. Then they generated sex positive imagery around HIV and positive experiences. These images were borrowed and sold back to the community as a kind of lifestyle so they can live. And this distances us from those images. It is hard to get back to us from the God of commerce.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: To be an activist now is to also create images. It is to generate content, so much visual production. The museum is one platform for producing that. But we are not dependent on that. This conversation can be had by anyone; it need not be only in museums.

AJ: It was an exciting idea when Gran Fury figured that out that they could generate widely circulated images. Now every single human being is generating images and I think the question becomes when is that image-generation activism?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Activist producers—Queer Nation, ACT UP, Gran Fury—created an arsenal. It is such a good primer. How do we take from those tactics? That is the value of How to Survive Plague.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: The role of art is to make a conversation and the form.

If nearly everyone makes images today that is undeniably a good thing. Increased distribution of voice is an activist goal that I have been articulating throughout this piece and across my own activist history.[33] But, the words I chose to conclude with, from the audience member at MOCA, help me to focus upon how the fostering of conversation between image-makers becomes a critical scene and action for activism in this time when image making and circulation have been almost fully democratized. While we used to make the art that then inspired the conversation that fueled the activism, our maniac art/image making today, locked as it is in our reiterative screens, private homes and corporate platforms, keeps us atomized. Thus, our political form and format must link from the self-image to include the conversation. We need to organize our interactions with the same care, theory, and commitments that we previously applied to our activist art making.[34]

And, this everyday yet ever more rare form of knowledge production—conversation in all its confusing, pleasurable, painful, inter-subjective delight and disharmony—is also, with hindsight, what we often do see in the Alternate Endings videos, perhaps instead of or as ‘activism’ and instead of overt sexuality: conversations between ex-lovers negotiating sero-discordance, between artists in the present striving, through the magical and mobile time practices of video, to connect with their lost friends, lovers and forbearers. With pornography being the most-seen images on the Internet, porn-porn, perhaps we don’t see graphic depictions of sex in these activist art videos because those images are as defanged as those of ACT UP street activism. Meanwhile, face-to-face conversation has become increasingly hard for us to do and see, even as speaking our own point of view becomes easier. In his writing on PrEP, Kane Race describes how biomedical HIV prevention methods have stripped away the hard conversations about sex, desire, fantasy and daily experience from the work once called ‘safer sex education.’[35]

I will end this essay trying to think about the form and function of ‘hard conversations’: what makes them feel political or activist and not merely delightful, difficult, social or ordinary? But before that, I will take one more home-tour, through some contemporary depictions of an HIV that is controlled, absented and domesticated. This contained and comfortable version of AIDS has become an even newer visual dominant for reasons that are not mysterious: because of who controls stories of the past, who has access to mainstream audiences of the present, because of what was best recorded and is most easily available in the archive, because of what has become safe through both nostalgia and biomedical fixes.

Being Comfortably at Home with HIV: The New Everyday (for Some)

AIDS activist video has always been, in part, a project of people of color, women, children, transwomen and disenfranchised gay men; in the United States and globally, they are sharing their specific, everyday knowledge. For a while, gay white men were so radically impacted, suffered so monumentally, that their resources, faces and complex experiences became central to the movement’s political projects and demands. But (thankfully) pills have entered many of these bodies, and for them, AIDS, indeed, might ‘be over’: a horrible and sad spectre of the past but not a crisis of the now, the everyday, and certainly not one for the future. ‘No longer a social, political, and cultural crisis, AIDS appears as scientifically quantifiable risk with a biomedical/biotechnological solution.’[36]

When I attended the Berlinale in 2016 to screen the twentieth retrospective re-master of Cheryl Dunye’s 1996 The Watermelon Woman, the first African-American lesbian narrative feature film (which I produced), I asked the programmers to point me to films that focused upon HIV/AIDS. I had made this same request each of the four times I attended the festival over the past twenty years, since the Berlinale, a remarkable film festival that is at once ‘A level’ (meaning the ‘highest quality’ of films that should have the broadest impact by reaching a generic ‘world audience’), is also deeply and meaningfully queer. In other years, I had seen all the AIDS films, usually countable on one hand. This year, I saw four of the nearly fifteen films the programmers listed for me: Who’s Gonna Love me Now?, Uncle Howard, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, and Kiki. The conclusions I draw from them are therefore neither total nor systematic. What I can say for sure is that the sheer number of films reflects something critical. Today, at least if the Berlinale is any indication (and it is a major market where television, festival and theatrical sales for media are made for the year, so it points to what most of us might be able to see), we find that AIDS narratives that manifest within queer, made-for-broadcast documentary-fare, show HIV newly: as permissible, common, to be expected. As is true of queer representation more generally, the HIV/AIDS part of the story has become just that, part of the story: not its problem, climax or focus. Don’t get me wrong; this is, at least at first look, a good thing. In these films, HIV/AIDS becomes integrated, or embedded, into the larger fabric of the characters’ daily lives, as well as into the cinematic style that holds them there. Here we see yet another kind of homing, a different form of domestication.

Uncle Howard, Mapplethorpe and Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? are documentary portraits of gay white male artists, albeit with varying degrees of fame and longevity. The first two films’ lead characters, Howard Brookner and Robert Mapplethorpe, died in the 1990s before HAART, while Saar Maoz lives under the still-real menace of a biomedically contained HIV. Yet, for all three characters, HIV/AIDS is a central force in a life where career and personal goals are curtailed by both the virus and related homophobia/AIDSphobia. After years of silence, we see AIDS named openly, almost off-handedly. No closet. No fuss. No muss. In conversation about this effect, Theodore Kerr remarked to me that a good deal of his political work of the last decade has been committed to demanding just this: ‘permission to name it. To say AIDS in the room.’ But Theodore means more: when you say it, what makes it hard and risky is that the word ‘AIDS’ is articulated as political, as part of a coherent critique connected to a collective project of working for change. He means: if you say AIDS in the room, the room should change. Things should get complicated, messy, perhaps destabilized, and then discussed and maybe for a few minutes, figured out, through conversation.[37] Rather than drawing out ‘an AIDS-free generation: pristine, optimistic,’[38] these harder conversations bring forward an HIV/AIDS and its community that may be suppressed but is always multi-valent and never easy.

Even as they ease into a relative comfort with HIV, these films are by no means apolitical. Each is invested in its own project of world-changing. Uncle Howard embraces a liberal project of acceptance, tolerance and remembrance. Howard’s straight nephew and the film’s maker, Aaron Brookner, sees himself in the archival footage and present-day interactions with living friends of his long-dead gay uncle. His quest for connection and understanding moves his narrative. In Mapplethorpe, Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato draw an elegantly dark argument about how homosexuality, sexual deviance and even HIV/AIDS become marketable within celebrity culture and its ever-tighter relations to the art world through the AIDS, death and salesmanship of Robert Mapplethorpe. Who’s Gonna Love me Now? engages in ‘pink-washing,’ a depiction of Israeli culture (the film is a made-for-Israel-TV documentary) that is open to homosexuality as a way to displace the gaze from the culture’s intolerance of and violence against Palestinians.

And in each film, the protagonists live with HIV in a (highly mediated) domicile. Always a camera recording, the documentaries are built from home movies and newly produced images of private lives that have been determined, altered and, in two of them, ended by AIDS. The early AIDS that fells Brookner and Mapplethorpe is categorically brutal and unfair leaving still-mourning friends, family and colleagues in its wake (interviews with whom form much of the ‘present’ of these archive-dependent documentaries). This horrific AIDS is revisited through their testimony and illustrated by haunting and gruesome returns to images of illness and death represented in home movies of lives lived in and through media. What remains present of AIDS of the past is a past horror and a lingering loss.. For the Heymann Brothers, HIV/AIDS is a dramatic plot-point that initiates their character’s search for connection, care and home. Maoz is forced to choose, cruelly, between his life as an artist, enmeshed yet still lonely in London’s flourishing gay scene and particularly its Gay Men’s Chorus, or his place within his largely homophobic/AIDSphobic but nurturing religious/military/gender-segregated family on the Israeli Kibbutz where he was raised. At the film’s finale, he chooses Israel, and in an important twist, interviews for a job there as an HIV-counselor. Maoz makes this initial step as a political awakening at the film’s end: to be out with HIV in his home of Israel.

This is one form of contemporary AIDS media politics. The three films look back to the archive of AIDS activist video from a position of present-day comfort for those who have benefitted by getting pills into their bodies.[39] But, as I’ve been arguing throughout, the majority of people affected by HIV/AIDS suffer from ill health on a day-to-day basis and live lives that are precarious because of innumerable and linked social, economic and larger health-related conditions that affect their experience of HIV. Theirs are not lives with ‘health concerns that can be bracketed off from intersecting modes of systematic discrimination.’[40] Most of the theorists I’ve engaged with throughout this essay name racism as one such systematic violence that affects the health of people of color, regardless of their HIV status. But, while it looks like we are seeing a successful civil rights movement in our time through the activism of Black Lives Matter, I think it’s fair to say that we don’t yet have a poor people’s movement in the United States. What does an activist visual politics of ‘Being at Home with HIV’ look like for poor people?

Steven Henderson dancing at the Cowboy Bar in Desert Migration. Photo Credit: 13th Gen Inc.

Here, I would point to three recent documentaries, Kiki (Sara Jordenö, 2015), Wilhemina’s War (June Cross, 2015), and Desert Migration (Daniel Cardone, 2015), all broadcast-ready feature documentary fare. Kiki is a revisit of New York’s black, queer ball culture, this time by Swedish female filmmaker, Sara Jordenö, twenty-five years after Jennie Livingston explored this scene to much acclaim and debate. This time the white female outsider collaborates with a member of the scene, the queer black gay man, Twiggy Pucci Garcon, who is both Father of a Ball House and a professional queer youth organizer. The images of daily life for the queer/trans youth of color who make up the film’s Kiki scene are infused, not by the comfort that exudes from the work I mentioned above, but by a politicized, theorized vocabulary that names the dangers and causes of their hostile daily lived conditions, including HIV, homelessness and systematic violence against queer and trans youth of color from their parents, their community and the police.

Willhemina’s War is embedded in the dailiness of brutal generational poverty for one southern African-American family for whom HIV is also just one in a list of struggles and conquests, suffered and fought through a rich if impoverished life built from love, community and organizing in the street, hospital and at the state house. Desert Migration focuses on aging (primarily) gay white HIV+ men who have moved to Palm Springs because it is warm, majority gay, and therefore replete with more AIDS/gay services than is true for most of America. The long term diminishments of an adult life defined by HIV (even if now managed by medication) is the focus of these dark portraits of home-life, replete with loneliness, self-doubt and a day-to-day denial of the dignity of work (because that is the only way HIV+ people can qualify for long term benefits in the US).

In all of these documentaries, as diverse in form and content as only AIDS activist media can be, I see variations on what Woubshet calls “a political sense of loss”[41] and what I name a political sense of home: the crafted intermingling of vulnerability and activity, loss and power, isolation and community, that condition the representations of our activities at home in daily proximity to HIV. Now, as ever, people with HIV live differently, need differently, represent differently. For example, Woubshet writes about how for Africans and African-Americans, a political sense of loss is built through defining experiences of time where the traumatic and violent past serves as inspiration for a traumatic and violent present that is always dangerous and precarious because the ‘paradigm of black mourning insists that death is ever present.’ This does not generate a stable, comfortable, being at home with the present, past, or future—a luxury not available for all—but rather, ‘a fierce political sensibility and a longing for justice.’[42] From this uniquely queer black temporality, he details how generative, sustaining artwork that can and must mourn and agitate is produced. As AIDS changes, how do we record and also create a ‘political sense’ of loss, home and time? How do we live, mourn and agitate?

Being in Conversation with the Home of HIV

The role of art is to make a conversation and the form.

Audience member, Alternative Endings

Conversation is a key genre of the present: when a conversation ends,

its singular time ends … it makes its own rules and boundaries,

its own terms of being contemporary and of taking over

what would otherwise be the arrhythmic rule of crisis.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism

My sense and use of queer time and place and their humble, loving handmaiden—video—is activist and pragmatic. But activism and pragmatism are themselves place- and time-bound. When video, in its awesome capacities to record and then share place and time, becomes ubiquitous, mostly corporate (in its ownership and platforms of circulation), and primarily atomizing, then the activist goals and uses of video must be rethought. When one form is emptied out of efficacy, others need to be invented. In this time of ‘cruel optimism,’ Lauren Berlant writes of ‘a kind of philosophical pragmatism that involves becoming a political subject whose solidarities and commitments are neither to ends nor to imagining the pragmatics of consensual community, but to embodied processes of making solidarity itself.’[43] Given that personal (and perhaps political) expression has become both easier and more isolating, I suggest that the artful staging of conversation might be what contemporary activist mediamaking needs so that we can sense it and ourselves as political amidst the onslaught of (our) images. Video can be used as one such tool to reach for that embodying of solidarity: to start the hard conversation and introduce the form.

In this and other work, I have suggested that the production and circulation of culture (as video, text message, analytical essay, FB post, no matter) is a necessary and vital step in activism; one that is proto-political.[44] Articulating and sharing our experiences, our criticisms, our ways of being and knowing and feeling can educate and inspire, and can contribute to self-healing or connecting to others. Jose Muñoz writes, ‘from shared critical dissatisfaction we arrive at collective potentiality.’[45] When that collective potentiality attaches itself to demands and associated actions, we are political. It happens all the time. But neither time nor place is inherently political, nor are the representational systems that we use to hold and share them. That’s what makes politics and political art so hard to do: the forging of connection with intention (to the past, present and future, to other places, to humans both alike and different from us). That’s what makes activism and activist art so rewarding: it gives us a political sense of and possibility for our daily experience and its representations. Activist AIDS video connects personal experience of HIV to larger systems, analyses and communities who have goals of making things better and also plans to get there. If this becomes untenable in contemporary media environments, than perhaps our conversations can better serve this role.

Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin, Your Nostalgia is Killing Me, 2013, Digital/Google Sketchup. Image courtesy AIDS Action Now and Poster/VIRUS (Toronto).

I am aware of, and closely connected to two contemporary AIDS cultural activists who are doing vital work in the theorizing and practicing of conversation. Since this essay is already too long, and they have done this work well on their own, I’ll end by pointing to the possibilities and pragmatics of the work of activist sound collective, Ultra-red and AIDS cultural activist, Theodore Kerr. Ultra-red has been initiating and thinking about collective ‘militant sound investigations’ as part of their work and mission, coming first out of AIDS activism, for over twenty years: ‘if we understand organizing as the formal practices that build relationships out of which people compose an analysis and strategic actions, how might art contribute to and challenge those very processes? How might those processes already constitute aesthetic forms?’[46]

I have been stating across this essay that aesthetic forms for activist practice take the shape of carefully orchestrated collective processes that both engender and emerge from objects; Ultra-red exemplifies this fully. They make their work through a refined, documented, and always-transforming process that is clearly articulated across their work, and most accessibly in their recent Practice Sessions Workbook, available online.[47] In the workbook, they walk their reader, and her community, through careful steps—organizing a team through an intentional invitation and grounded questions that are generated to produce both objects and actions through ethical practices. They write: ‘every sound exists in time and space. And since time and space are the building blocks of human activity and struggle, sound is a venue where perception meets action. It is where the body politic encounters the material.’[48]

Ultra-red, Vogue’ology Encuentro, The New School, New York, 2010. Photo by Darla Villani.

Similarly, Theodore Kerr has been staging conversations where ‘the body politic encounters the material’ concerning lively issues, art and potential futures for today’s HIV/AIDS activist community in New York and elsewhere. When the Your Nostalgia is Killing Me poster campaign produced volatile, energized and contentious debate on the ACT UP New York Alumni Facebook group (of which I am a member),[49] Kerr and his colleagues at Visual AIDS moved this conversation to a room: ‘no one event, or conversation is going to resolve the many issues we are all experiencing and working through. By creating environments, through art and culture, we believe we are setting up long term conversations between people, communities and organizations. …You are invited to come to “Your Nostalgia is Killing Me” with all your confusion, criticism, anger, joy, will, and love. And you are invited to work through and share what you bring, respectfully, with others.’[50] Kerr’s more recent work, with others, on ‘What Would an AIDS Doula Do?’[51] brings New Yorkers together not from active contention but from animated care. ‘A small and dedicated group of us have been meeting to discuss community care in relation to HIV/AIDS and the possible role of a Doula. You are welcome. Snacks. Free.’ In her thinking about AIDS video and writing, Berlant says: ‘but that is not all conversation is: in a crisis, vital information-trading proliferates and demands conversation across many media. Informal networks of knowledge sharing are central to the endurance and vitality of an intimate public.’[52]

Katherine Cheairs and Lodz Joseph for What Would An HIV Doula Do? Photo Credit: Theodore (Ted) Kerr.

When this intimate, political sense of daily life with HIV emerges—in our artmaking or crafted conversations—we are nourished and energized by disparate, local, specific and temporally complex home-views that are also world-views of diverse people’s inspiring hopes for and capacities to live, fight, and connect. Video that begins with the private, mundane, everyday experience of the personal becomes activist video when it connects to others and larger claims and demands. This is both harder and easier to do now. But if the internet sucks the life out of our images, we can revitalize them and ourselves through being in conversation (online, in-person, no matter) with the home(s) of HIV. Embodying solidarity by expressing our critical dissatisfaction and sustaining care, through words or images, in community, in conversation, with a commitment to world-changing is itself a queer, generative, time-rearranging practice. And of course, how we capture those words, images, ideas and connections, for those who can’t always be in the room, is ever the role of video.

[1] This title serves to represent, in form, one of my beliefs and commitments about academic/activist work: that it is done in conversation and in community.

[2] Silverlake Life (Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman, 1993) is perhaps the most obvious early example of a feature documentary that represents AIDS in the home as a political act.

[3] Shahani, Nishant. Queer Retrosexualities: The Politics of Reparative Return (Lehigh University Press, 2011).

[4] Woubshet, Dagmawi. The Calendar of Loss (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.).

[5] The seven videos in Alternate Endings were made by Rhys Ernst, Glen Fogel, Lyle Ashton Harris, Derek Jackson, Tom Kalin, My Barbarian, and Julie Tolentino/Abigail Severance and were curated by Tom Kalin, Theodore Kerr and Nelson Santos. Alternate Endings videos and other resources are available on the Visual AIDS blog: https://www.visualaids.org/projects/detail/day-without-art-2014.

[6] The full transcript and video of the conversations are available online, as part of the larger Day With(out) Art effort: https://www.visualaids.org/blog/detail/8963.

[7] Theodore Kerr and Bryn Kelly discuss incidental images of HIV in their conversation, ‘Diamond Dan and the Rise of the AIDS Punch line.’ Indiewire. October 7, 2015: http://blogs.indiewire.com/bent/diamond-dan-and-the-rise-of-the-aids-punchline-20151007.

[8] Theodore Kerr thoughtfully questions his own work within the AIDS activist community as someone who is HIV-negative and white in ‘Who is HIV For?’ WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 42:3-4, 2014, 333-338.

[9] The ethical considerations and consequences of Marie’s media visibility become a central theme of Chapter 6 of my AIDS TV: Identity, Community and Alternative Video (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995).

[11] We see proud black homeowners living with HIV/AIDS in Wilhemina’s War (June Cross, 2016), which I discuss later in the article. This was modeled early on by Ellen Spiro in Diana’s Hair Ego (1989).

[12] This fixedness of video in the face of death, as well as personal and political change is one of my foci in my writing on my video, Video Remains. ‘Video Remains: Nostalgia, Technology and Queer Archive Activism’, GLQ, 12:2, 2006, 319-328.

[13] I write about AIDS memorials (including images of Marie and Jim) in ‘Digital AIDS Documentary: Webs, Rooms, Viruses and Quilts’, in Juhasz and Lebow (eds.). Blackwell Companion to Documentary (Cambridge: Blackwell Press, 2015): 314-334.

[14] See much more on this history in AIDS TV.

[15] I discuss the returns of Gregg Bordowitz, David Roman, and myself to once verboten cultural objects in ‘Digital AIDS Documentaries.’

[16] Cohen, Cathy in Jih-Fei Cheng, ‘How to Survive: AIDS and Its Afterlives in Popular Media’, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 44: 1, 2, 2016, 73-92.

[17] This is term has been developed in conversation with Hugh Grant and Jean Carlomusto with whom I am curating Visual AIDS’ 2016 exhibition, EVERYDAY.

[18] Juhasz, ‘Video Remains, Nostalgia, Technology and Queer Archive Activism.’

[19] One of the landmarks of this preservational project, the ACT UP Oral History Archive by Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman, re-commits to our shared activist effort of recording the voices of the diverse people who participated in what is often otherwise only- or mis-remembered as a collective of wealthy gay white men. Making archival (media) space for the multiplicity of voices and analyses within this diverse movement is a stated goal: www.actuporalhistory.org.

[20] ‘AIDS Reruns: Becoming “Normal”? A Conversation on “The Normal Heart” and the Media Ecology of HIV/AIDS’, with Theodore Kerr, Indiewire, August 18, 2014: http://blogs.indiewire.com/bent/aids-reruns-becoming-normal-a-conversation-on-the-normal-heart-and-the-media-ecology-of-hiv-aids-20140818?page=1#blogPostHeaderPanel. And ‘Home Video Returns: Media Ecologies of the Past of HIV/AIDS’, Cineaste (May 2014): http://cineaste.com/articles/aids-article. Ghost Stories, by Marty Fink, Alexandra Juhasz, David Oscar Harvey, and Bishnu Gosh, Jump Cut 55: http://ejumpcut.org/archive/jc55.2013/AidsHivIntroduction/index.html.

[21] Shahani, Nishant. ‘How to Survive the Whitewashing of AIDS: Global Pasts, Transnational Futures’, QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 3.1, 2016, 1–33.

[22] As is true for their ACT UP Oral History Project, United in Anger (2012), the documentary which draws on this footage, by Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman, also commits to hearing the voices of women and people of color who were central to this organization and movement.

[23] I discuss why many AIDS activists at the time did not join ACT UP, or did not want to participate in street activism, in ‘Forgetting ACT UP’, ACT UP 25 Forum, Quarterly Journal of Speech 98:1, 2012, 69-74.

[24] Cheng. Unpublished draft of ‘How to Survive.’

[25] Geary, Adam. Antiblack Racism and the AIDS Epidemic: State Intimacies (Palgrave, Macmillan, 2014).

[26] See my ‘Forgetting ACT UP’, for which I interviewed AIDS video activist colleagues who were not members of ACT UP. Juanita Mohammed, a member of WAVE and also a media activist who made work for GMHC told me: ‘I guess I never became a member of ACT UP because I saw myself as other than the members. For the most part they were educated, White, gay men who talked in a high-fallutin’ manner. Whenever I gathered up the nerves to engage ACT UP about becoming a member or getting involved in activities other than attending a rally or march, they seemed aloof, I did not feel welcomed.’

[27] Ghosh, ‘What Time is it Here?’ Jump Cut 55: http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc55.2013/GhoshAidsGlobal/index.html.

[28] Kenyon Farrow, http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/12/young-gay-black-and-at-risk-for-hiv/265792.

[31] Juhasz, ‘Acts of signification-survival’, Jump Cut 55: http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc55.2013/JuhaszAidsDocs/text.html.

[32] Ryan Conrad explains, in an email, that his students prefer Silverlake Life (Peter Friedman and Tom Joslin, 1993) and Fast Trip Long Drop (Gregg Bordowitz, 1993), because they ‘offer a counterbalance to the images of vibrant heroic activists with the reality of our fear, frailty, and ultimate destruction.’

[33] This is the guiding question of Learning from YouTube, where I work through, in community, why near universal access to production and distribution of video hasn’t produced the revolution many of us media activists had predicted. Learning from YouTube (The MIT Press, 2011): https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/learning-youtube-0.

[34] The AIDS activist artwork of the Ultra-red collaborative theorizes and practices conversation. I will attend to some of their work in the conclusion: http://www.ultrared.org/mission.html.

[35] Race, Kane. ‘Sexual Pleasure as a Problem for HIV Biomedical Prevention’, GLQ, 22:1, 2015, 7.

[37] One of Kerr’s many forms of AIDS activism has been to host just such conversations, in public, around contentious or complicated issues within the ‘AIDS community’: like the ‘Your Nostalgia is Killing Me Campaign’, (a poster by Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin) see: https://www.visualaids.org/events/detail/your-nostalgia-is-killing-me-a-catalyst-for-conversation-about-aids-and-vis; the controversy about my own article, ‘Forgetting ACT UP’; or his newest conversations: ‘What Would an AIDS Doula Do’, http://hivdoula.tumblr.com/post/138557273724/what-would-an-hiv-doula-do. I consider these conversations in the conclusion.