Joshua West Smith

All images by the artist.

To make is a difficult thing. To know why you make is sometimes equally as hard. And to share your passion for making and to help others in their personal creative journeys is a uniquely querulous thing. As a truly gifted maker and educator Karl embodies all of those roles with rigor, passion and seemingly undying energies.

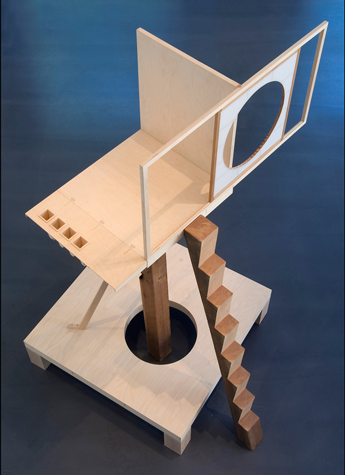

Bit, 2013, Plywood, wood and paint. 48 x 96 x 96 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

Joshua West Smith: I know you as both an artist/maker and an academic. I think you approach both with a similar style and possibly with similar questions. Can you address some of the concerns you bring to both undertakings and add a bit about how the two roles have influenced each other?

Karl Burkheimer: I am reluctant to separate or marginalize any of my creative endeavors from another. I walk into my studio, and I may make a jewelry box for my wife’s birthday, build countertops for my kitchen, construct a decorative structure for an architectural commission, or finalize a piece for a museum exhibition. The creative engagement is all the same, stemming from the same capabilities, interest and knowledge. I am particularly reticent to set my academic and creative practices at divergent purposes. In many ways I view the separation as a false dichotomy, since both emanate from the same sensibilities and motivations.

Without any suggestion of self-deprecation or apology, my practice as an academic makes me a better artist; it’s possibly what makes me an artist at all. I view and utilize the academic arena as a fertile environment for discovery, and my students fuel a perpetual sense of wonder: accepting nothing as absolute, seeing the ordinary and noticing the miniscule. More importantly, my students silently push me, demanding that I walk my talk. Essentially, if I have the audacity to stand in front of them challenging and pressing their creative practice, I must also perform, taking creative and expressive risks while continually striving to find a strong, current and relevant voice.

Art-based academia has its problems that are well documented and continually opined. I could dwell on the drawbacks my academic career poses to my studio practice, but as I said before both function concurrently within my creative life. Difficulties, constraints and limitations are creative opportunities. My teaching—both voice and method—and my practice are founded on the creative strategies and methodologies for negotiating the mindfulness of intentions in relation to opportunities of discoveries. In this manner my classroom becomes as much of a creative endeavor as any aspect of my studio practice. Not only would it be hard to separate the two, I do not care to even consider them in isolation.

In-Site, 2011, Plywood, wood, paint. 43 x 500 x 800 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

JS: In the last few years you have made some work that is really large. Two of these works, In Site (2011), exhibited at Disjecta Contemporary Art Center in Portland, Oregon, and Setting a Corner (2013), exhibited as part of the Contemporary Northwest Art Awards at the Portland Art Museum, truly dwarf your smallest works, which are a series of carved wooden objects that fit in the hand. Can you talk about scale and how it is currently operating in your practice?

KB: While I enjoy the extremes of scale within my work, I struggle with uncertainties regarding the rationale. The paradox is not the disparate scales but my suspicion of the masculine/heroic as well as the fetishized/precious, yet either could be an applicable descriptor of the work.

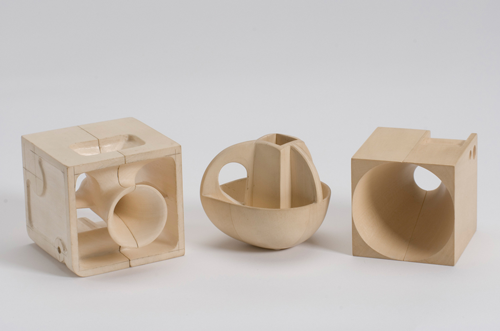

I suspect architectural archetypes play a role regarding the size of the work, though my small works do not function as models or maquettes of the larger work. However, these small handheld objects are condensed, abstracted expressions analogous to the ideas investigated in the larger work—concepts rooted in exchange.

As you said, the small work fits in the hand, directly referencing how they are made but more importantly the manner they should be viewed in. Uncomfortable on a pedestal, especially under a vitrine, these objects are best understood and invigorated by being held. Likewise, the large work responds to a haptic understanding. Operating in the scale of the built environment—walls, floors, etc.—the hand-held aspect in the large work is the clarity of the materials—sheets of plywood, concrete blocks, etc.—hand-held units of construction.

The relationship to the hand is often my intended point of exchange with viewers, whether they are allowed or able to touch the work or not. The desire to touch, or the ability to intuitively understand the texture, weight, and so on, is an axiom in my practice.

Setting a Corner, 2013, Plywood, wood, steel, paint, gravel. 148 x 220 x 200 inches. Photo: Karl Burkheimer.

JS: I wanted to draw a parallel between your work and that of Gordon Matta-Clark, who often seemed to mine the spaces between construction and destruction. This space of the ruin was fruitful because of the physical freedoms it afforded him to create large works and deepen the metaphorical implication of his actions. What conceptual links do you see between Matta-Clark’s work and your own?

KB: I do not remember my first introduction to Matta-Clark, but it is a safe bet that it occurred as a projected image offered in a typical undergraduate art or design history course. While my recollections of the discovery are vague, the affects continue to resonate. As a young architecture student Splitting (1974) challenged my simplistic views of materials, expanding my ideas of materials from mere units of construction—bricks, wood, concrete, etc.—to concepts of architecture as material. That revelation continues to serve my creative practice, providing a fluid interpretation of material/object relationship; materials converted into objects, objects assembled into wholes, wholes constructing context, environments divided into units, units broken into pieces, pieces becoming material. This infinite facture of material transformation is not necessarily a conceptual driver of my work, but the permission it grants me either through making things or contemplating things is invaluable.

Yet Splitting was more influential to my work than material freedom. The heroic and laborious act of cutting a house in half is beautifully mitigated by the simplicity of the gesture. An everyday thing, an average house, cut in half as casually as cutting into a loaf of bread: revealing structure, disrupting continuity, cleaving the whole and laying bare the hidden. While the internal may be known it is so easily dismissed or forgotten as merely the messiness or necessity behind the surface. Splitting the house released the pent-up energy of making the house, living in the house, maintaining the house: the exposed, the unseen and the un-contemplated.

Setting a Corner detail, 2013, Plywood, wood, steel, paint, gravel. 148 x 220 x 200 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

I can imagine the thrill of cutting the house, coarsely but with an adept skill and knowledge of what lies beneath the skin, understanding that the violent/surgical act was a beautiful reveal that became a ceremonious act, maybe a brief pause, in the house’s demise—returning it to material. In this suspended state of ruin the life of the house is enhanced by the knowledge of its ultimate loss and its value relegated to memory as well as the salvage price per ton. Matta-Clark created beautiful ruins that, in my opinion, spoke as strongly about the making of art as the un-making of artifact, the continuous cycle of making, re-making, un-making, re-making, making.

But it is the film by Matta-Clark and Bruno de Witt of Matta-Clark’s Conical Intersect (1975) that remains one of the most relevant influences on my work. The film begins with the creation of a small rough hole high above the street. The hole gradually grows, pulsating from the simple and harsh act of using a sledgehammer on a masonry wall from inside the building. The stark simplicity of opening a portal is paired against the brutal labor of building a hole through the force, skill and vision of destruction. In the background the Centre Pompidou, an infamous example of postmodern architecture, is being constructed—its complex form rising from the destruction of dirty, worn, old masonry buildings and casual, mundane everyday life in Paris. The juxtaposition of the everyday with the spectacle, construction with destruction, making with un-making, is categorically a foundation of my work and practice.

Years ago I attended a lecture by designer Tony Fry. He made a very simple but infinitely poignant comment, which sums up my thoughts about the influence of Matta-Clark’s work on my practice: ‘making something always requires the destruction of something else’.[1]

Apropos, 2012, Plywood, wood, paint. 64 x 26 x 20 inches. Photo: Karl Burkheimer.

JS: Your work seems to thrive in the construction but hinge on the void. Can you speak to your use of the void in your work?

KB: Yes, I am deeply intrigued by constructing absence. On one level making nothing is closely related to destruction—the removal of the built and leaving the void. Certainly, Matta-Clark’s work is brilliant and offers beautiful negotiations of transformation, but, as you mentioned, I think my work is more focused on the construction of nothing. I am particularly inspired by Martin Heidegger’s discussion of the thingness of the vase (or jug) in his book Poetry, Language, Thought (1971). He contends that the void of the vase is the thing or essence of the vase.[2] The making of the vase, all the skill, materials and tectonics are in service to the void. The potter shapes the emptiness through the making of the sides and bottom of the vase.

In many ways I consider architecture a shaping of emptiness. Space cannot be directly manipulated; it is designed/created through the secondary or indirect act of making objects—and arguably images—that define it. The nature and character of a space is created from the energies and capabilities of making discrete things, objects.

I make a lot of holes. At times I bore holes through found things, sometimes I build things to bore holes into. Other times I construct holes by building the perimeters, but in either case a lot of energy and effort is directed to allow for a nothing. Ontologically the hole intrigues me; whether it creates a portal or a void, an abyss or a passage, the building of a not-thing is a curiosity. I do not consider the notion of building a void a stunning revelation (and it is certainly not a unique concept), but it has offered me a vast spectrum of opportunity, especially as a maker dedicated to art and the act of transforming material into things.

In-Site detail, 2011, Plywood, wood, paint. 43 x 500 x 800 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

JS: We have had many conversations about your reticent to apply the term ‘sculpture’ to your works. Could you expound upon this distinction, and why you refuse ‘sculpture’ as an easy label for your work?

KB: I often find myself in this discussion, and I freely admit that my motivations to engage or provoke the dialogue are at times simply political positioning. I also understand that my work generally operates as sculpture. It is consumed and invited through artistic institutions and constructs (i.e. this article for Drain), and I am culpable. I pursue those opportunities and contexts, yet I believe my work stems from a different place than sculpture.

I base my argument mostly on parentage. While my work may look like art, the lineage of my work and practice is clearly derived from making/design. And, at the risk of gross generalization, I believe that sculpture (art) owes more to visual contemplation than haptic knowledge or the negotiation of purpose. Michelangelo’s David (1501) is an image to gaze upon, not touch. The exquisite capabilities of carving a beautiful piece of marble are a means to have the image and story of David transcend the materiality of stone and the practice of stone carving. I am not specifically motivated by such transcendence because my work, the art, is about the making, and the transformation of material into form and meaning.

Humans exist and thrive in the built environment, and the built environment fascinates me. My voice as an artist/creative is rooted in that fascination. Basically, I go to my studio and I make things. Sometimes the outcome is intended to be practical/useful and sometimes it is meant to be contemplative/expressive. I do not need to justify my creative practice as a mechanism or method for producing art. The meaning is the making; the making is not merely the means to meaning.

Also, sculpture is a very tired, vague and at times boring word that is at risk of meaning nothing, yet loosely describing not-painting, not-architecture and not-functional. I hesitate (here comes the political rant) to continue such a nonsensical definition. Sculpture should be art (‘Art’) and if, or when, I make art it needs to be more than just derivative of things that look like art or things that are designated as art simply because of their questionable utility. Nor should my work simply default to sculpture because it is exhibited/published in an art environment or because it operates as an object of contemplation.

Basically, the term sculpture is limiting in its broadness. I am interested in a larger discussion about objects and object making that the category of sculpture seems to obfuscate. I intend for my practice and work to exceed a simple labeling as sculpture, and I want sculpture to mean more than an ill-defined category of art things.

Proximate, 2009, Plywood, pine, paper. 114 x 78 x 74 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

JS: As a final point I would like to address your collection of artifacts, which are in various states of ruin in your garage, and laden with potential. Your creative practice, and desire to blur boundaries in that practice, seems to be perfectly captured by your dedication to these machines, which you ardently keep non-operational and in a perpetual state of alteration. This is the part of the Barbara Walters interview where she would try to make you cry. I want you to confess the number of machines, and what they are.

KB: When I was a boy I used to build plastic models of planes, ships and cars. No matter how careful I was the end product never matched the photo on the box. Whether the result of a gluey thumbprint, a wrinkled decal, blotchy paint or a moving part that was glued in an unfortunate fixed position, the final model was a poor toy and a worse trophy. Inevitably these models were systematically destroyed, either violently with the unapproved use of pyrotechnics or through a slow deconstruction.

I remember always having a box full of model parts from failed or boring constructions, usually car parts, remnants of models that were surgically cut or less gracefully pried apart. From these parts strange and clumsy Frankenstein vehicles would be assembled to, once again, face destruction. The cycle became far more satisfying than the original build.

My garage is a small step from that box of model pieces under my childhood bed. With age and a professional income I can now play with a few old British motorcycles and a British sports car. Postwar British vehicles captivate me. These cobbled together machines (in design and manufacturing) perfectly melded a rural vernacular (a farmer’s DIY attitude) with a modernist, European flair for design and manufacturing. Of questionable utility and demanding spirit, these vehicles are well suited for perpetual states of ruin, rebuilding, failure, modification, restoration, failure, ruin and so on. I am particularly fond of a certain BSA motorcycle that I obtained from one of my MFA instructors. It is truly a hateful machine that taunts me as much as I curse it. Though it sits in the garage more than it is ridden, it receives far more creative attention to form, function and detail than I have given to any other machine before or since.

Small Artifacts, 2003-2008, Carved wood. Each 3 x 3 x 3 inches. Photo: Mark Stien.

It is often said that ‘perfection is the enemy of good’. Sometimes I am not even really interested in good… just doing. These machines that clog my garage are forever ‘in-process’, never perfect, never done, never resolved; but they are always interesting, always challenging, always provoking. They are continually in flux, spanning ruin to resurrection, a condition of infinite intrigue in my creative practice.

This interview is sequel to Making Awareness: An Interview with Joshua West Smith, published in the Molecular issue of Drain – Vol. 11:1, 2014

[1] Tony Fry. Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice (New York: Berg, 2009).

[2] Martin Heidegger. ‘The Thing’, in Albert Hofstadter (trans.). Poetry, Language, Thought, (New York: Harper & Row, 1971).

Karl Burkheimer is the Chair of the MFA in Craft at Oregon College of Art and Craft (OCAC). He received his MFA from the Department of Crafts and Material Studies from Virginia Commonwealth University and a Bachelor of Environmental Design in Architecture from North Carolina State University. Karl’s artistic practice is founded on an interest in labor and skill, reflecting many years of personal experience building objects and environments for both artistic and utilitarian purposes. He was a finalist for the 2013 Contemporary Northwest Art Awards at the Portland Art Museum, and a 2013 U.S.-Japan Creative Artist Fellowship. His work has been exhibited nationally, including recent exhibitions at the Disjecta Interdisciplinary Art Center, the Museum of Contemporary Craft in Portland, OR and the Society for Contemporary Craft in Pittsburgh, PA.

Joshua West Smith received his BFA from the Oregon College of Art and Craft in 2008 and is currently working toward his MFA in visual art at the University of California Riverside. Before returning to school, Smith was a welder fabricator and machinist. Since 2001 he has owned and operated jjfab a design build entity specializing in home furnishings. Additionally, Smith is one half of the curatorial team TILT Export:, an independent art initiative. jjfab.com