Karl Burkheimer

Josh and I have known each other for many years, interacting through numerous and ever-evolving capacities, but our innate connection is rooted in a shared sense of making. Josh’s art is steeped in a deep-seated curiosity and enthusiasm regarding the processes of converting materials into form and meaning, yet these interests and abilities are merely an undercurrent; his work delivers through strategies and explorations of awareness.

All images by and courtesy of the artist.

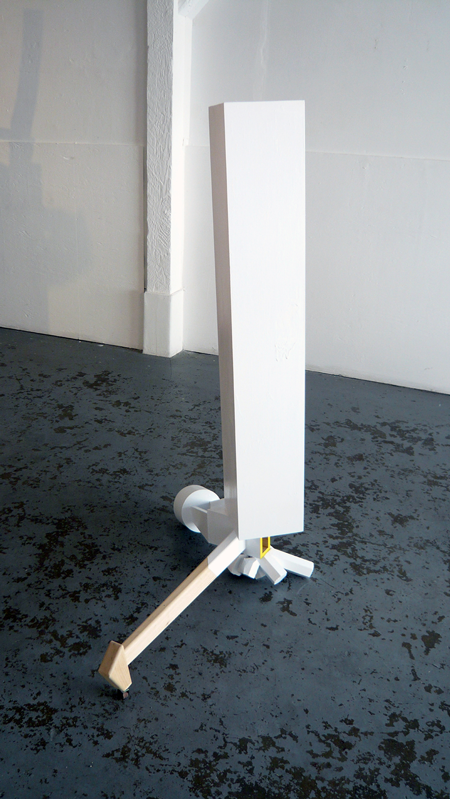

service, 2008, Ply-wood, foam, acrylic, 56 x 13 x 42 inches.

Karl Burkheimer: You and I share a similar history. We both developed an art practice subsequent to working in the building trades. Do you have insight regarding the relevance of your experience as a metal fabricator to your present artistic practice?

Joshua West Smith: I think one of the jokes I tell about myself is that I primarily use wood in my artistic practice because my fabrication background ruined metal for me. It has taken me a long time to shake some parts of my fabricator brain, like planning and measuring and getting really hung up on making the “Thing” perfect if not overly complex. Did I mention my problem with measuring?

Outside of breaking myself of old habits I think the same part of me that loved being a fabricator gets great satisfaction from the making I do as an artist. I entered industry because I was fascination with process, knowing something from the raw form to completion. As a fabricator I enjoyed seeing the many small parts I was tasked with making coming together to create some crazy thing that was so much more than its individual parts.

The company I worked for made hydraulic and pneumatic cylinders that ranged in scale from tiny things that could fit in your hand to enormous units that open and close dam control gates. This exposure to industrial scale blew my mind. I became hyper aware of not only the systems that I was building but of the larger systems that the objects I was making would engage, becoming yet another part to an even larger whole. At the time I was thinking of the question of a micro/macro view, but more recently I have begun to think about systems as existing in a spectrum, which pushes me to think outside of just big or small. This is a subject I am acutely attuned to, and I am constantly struggling with through my artistic practice.

Working With Doubt, 2010, Wood, plaster, latex, dry erase board, 72 x 55 x 18 inches.

KB: Speaking of the the art of assemblage, specifically fabricating, modifying, or adapting parts to combine collectively with the ultimate goal of creating a distinct larger whole, your work, both objects and images, seems to benefit from your sophisticated sense of construction, thriving within a sensibility of the made.

JS: I’m going to go out on a limb and just say my work in the rawest sense is about asking people to look at something with a critical and curious eye. A way that I do that for both the viewer and for myself is to set up interrupts in the objects or images that I make. The interrupt manifests through my studio practice in a few different ways. I am always making parts and objects that will migrate around my studio being matched with other orphan objects until I see a relationship. I think the interrupt for the viewer varies but often manifests in a recognizable language of collage. This allows the work to tap into an unexpected place, becoming something more than I could have planned. It’s kind of like collaborating with myself. You mention the made, which is a main focus of my work. I spend a lot of time thinking about and referring to the made as constructs and construction which I think covers everything from a simple composed image to systems of language that allow us quantify the world.

Running Line, 2010, Constructed plywood tubing, carved soapstone, 33 x 17 x 9 inches.

KB: So, your focus on navigating systems is a creative strategy for seeking solutions or possible a mechanism for problems seeking.

JS: I’m always trying to make things that are a bit out of control, including both physical and mental constructions. When I’m making I often think about the idea of the stopgap. I think a stopgap, or a temporary solution, appeals to me because it is an improvisational reaction to a specific and pressing need. I am constantly creating and engineering situations that I need to get myself out of, basically building the scaffolding as I go up. For me that kind of activity becomes a really nice poetic mirror to my life and the construction of my reality.

dirt poster – thinness, 2013, Plywood, soil, enamel paint, 14 x 12 x4 inches.

KB: This embrace of systems seems to fall in line with Jorg Heiser’s assertion in his 2008 book, All of a Sudden: Things That Matter in Contemporary Art, that contemporary art emphasizes method and situation over a historical focus on biography and medium. Can you expound upon the relationship between your process and your outcome?

JS: I’m rather certain that you are the person who introduced the notion of the game into my creative practice. It is that notion of the game that allows me to solidify the strategies I use to make work. For me just acknowledging that methods and situations could be implemented, arranged and changed became a productive engine for me. As an awareness I also think that method and situation refer solidly to Guy Debord’s notions of the Spectacle. In relation to this I am conscious of how the things I produce fit into that prismatic spectrum of the spectacle and hope to locate them nearer to the unique experience that allows for self-discovery and openness to a pluralistic interpretation. Because I feel that my finished pieces are so much about process and construction and indexing how I hierarchize my own craft, the outcome becomes a complicated manifestation of my desire to render ambiguous objects that incite both scalar and discordant thought processes.

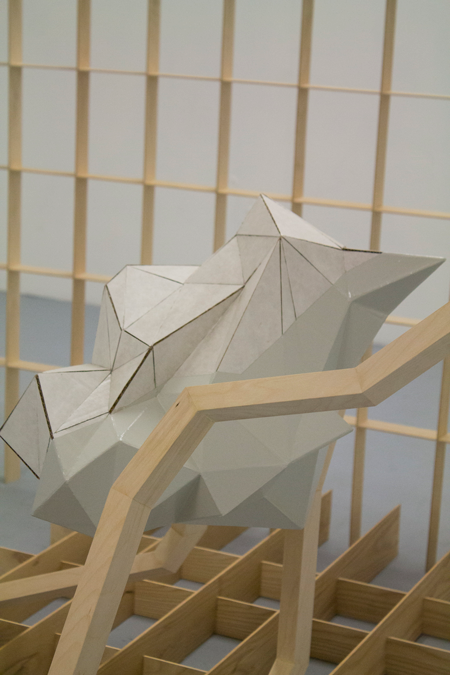

end of running line, 2013, Constructed plywood tubing, wood, cardboard, plaster, acrylic paint, 60 x 64 x 66 inches.

KB: You have mentioned awareness several times throughout this conversation. Awareness seems crucial to any art practice. How do you cultivate and/or capitalize on awareness? Is it merely a function of observation and curiosity or are you also implementing a strategy regarding awareness?

JS: For me an art practice has everything to do with awareness or presence or being present. A lot of what I do is intuitive or instinctual, and lately I have been contemplating the potential that some of my aesthetic decisions and proclivities are really linked to a phenotype in my genes. To be more direct about how I am conscious of facilitating awareness or presents I would site my belief that these two things are most readily provoked as a response to discomfort. As an act of cultivating or harnessing the discomfort, I employ the gaze of my subjective self and decide at which uncomfortable scale I would like to interact with something, be it an idea or an object, and I delve into the thing I want to understand knowing it will always evade my true understanding. All I can do is wrestle with it and try to represent my abstract understanding through what I make. This kind of answer maybe over exaggerates my existential angst but I do think the more closely I investigate my natural creative process, and the more I identify my motivators the more I realize I need to kind of bury that shit so I can make some work.

(Detail) end of running line

KB: Architectural ideas are often conveyed through models, whether conventional scaled replications or abstracted archetypal images, both of which seem to be prevalent in your work.

JS: I naturally gravitate toward logic systems and in general really respond to a visual language rooted in an architectonic vernacular. A result of that thinking is the work manifesting as an infinitely scalable unit that is in conversation with architectures (or the built environment) of all scales; from the immaterial models of morphology, to actual buildings, to the ideas of cosmic scale. I also utilize the language of the model as a nod to potentiality. If a model is nothing else it signifies potential and ambition, which as a repentant pessimist (read realist) I cannot help but be intrigued by.

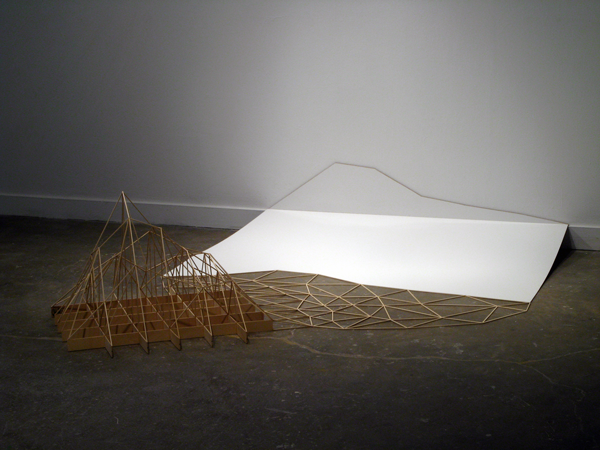

holy mountain, 2011, Wood, dry erase board, 32 x 48 x 65 inches.

KB: How does the architectural archetype specifically operate in your work?

JS: Like the latent potential of a model I think that architectural archetypes in general are imbued with the power to make us trust. Utilizing these trusted signifiers allows me to push other elements of the sculpture and imagery further toward extreme imbalances or absurdity. architectural archetype=trust anchor

Untitled_2014, 2014, Wood, steel, cardboard, stone texture paint, 72 x 44 x 44 inches.

KB: I am aware of your interest (if not obsession) in the mechanical, especially your affection for machinery, yet this interest is not apparent in your exhibited work. Does this interest operate outside of the work or is it concealed within it? Maybe it is only a tangential concern or consideration?

JS: I still have a compartmentalized relationship with my machine desires and my fine art output. That is not to say however, that I am privileging one over the other, I just haven’t figured how to make them work into what I am making at this time. Sculpture for me is about creating a dynamic form in space which has a lot in common with machinery. So it’s in there, just a bit hidden.

KB: But the real heart of my question is one cylinder or two?

JS: That’s a crazy question out of context. Is it a desert island scenario or are we talking my garage?

KB: I’ll take that to mean one cylinder.

Joshua West Smith received his BFA from the Oregon College of Art and Craft in 2008 and is currently working toward his MFA in visual art at the University of California Riverside. Before returning to school, Smith was a welder fabricator and machinist. Since 2001 he has owned and operated jjfab a design build entity specializing in home furnishings. Additionally, Smith is one half of the curatorial team TILT Export:, an independent art initiative.

Karl Burkheimer is the Chair of the MFA in Craft at Oregon College of Art and Craft (OCAC). He received his MFA from the Department of Crafts and Material Studies from Virginia Commonwealth University and a Bachelor of Environmental Design in Architecture from North Carolina State University. Karl’s artistic practice is founded on an interest in labor and skill, reflecting many years of personal experience building objects and environments for both artistic and utilitarian purposes. He was a finalist for the 2013 Contemporary Northwest Art Awards at the Portland Art Museum, and a 2013 U.S.-Japan Creative Artist Fellowship. His work has been exhibited nationally, including recent exhibitions at the Disjecta Interdisciplinary Art Center, the Museum of Contemporary Craft in Portland, OR and the Society for Contemporary Craft in Pittsburgh, PA.