Emma Campbell

While loss and impermanence are necessary facets of human existence, they are not always at the forefront of our everyday experiences. San Francisco-based artist Elisheva Biernoff captures the quiet and somewhat hidden aspects of the precarity of human life through her works, which often employ trompe l’oeil, or aspects of visual deception. Yet, the sense of loss and fragility is not always made immediately apparent in Biernoff’s work; in creating images that appear as one thing but are in fact something else completely, the artist alludes not only to our collective sense of loss through the atrophying of the human mind over time, but also to the imminent threat of our demise at the hands of an inherently unruly natural world. In Biernoff’s world, nature and humankind are intrinsically linked, and inexplicably at odds—a tension that perhaps holds true in all worlds.

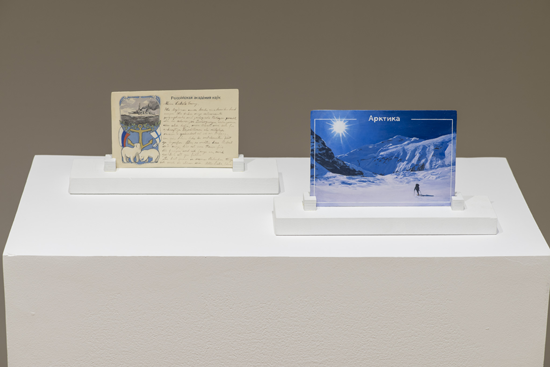

Elisheva Biernoff, They Were Here (installation view), 2009. Image courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

Between September 5th and November 15th, 2015, the Walter Phillips Gallery at The Banff Centre exhibited Without, within, Biernoff’s largest solo exhibition to date. The exhibition comprised two rooms, (eponymously, one without and one within) with earlier works showcased beside ongoing projects. When we enter the first room, we are confronted with three separate stations. A series of small works perched on plinths to the left drew attention to the corner of the room. At first, these works appear to be unassuming old postcards, but upon further investigation we see that they are in fact meticulously painted replicas of postcards from a range of eras and origins. The messages written on the back are by turn love letters, suicide notes or messages to friends and family, and though fictitious, all are inspired by historic figures who have mysteriously gone missing, oftentimes while adventuring in the wilderness. The Lost Postcards series (2009 – 2011) reminds us—at times painfully, at others nostalgically—of the precarious nature of life, as well as our relationship to our own histories and those which are lost. The works in this series collapse intimate, personal stories with collective human narratives, to compel thoughts of our ultimate impermanence here on this earth. They provide a soft reminder of the frailty of life, while also emphasizing the preciousness that exists in temporality.

Elisheva Biernoff, Without, within, 2015. Photo courtesy Donald Lee.

Long Story Short (2011) is a silk-screened book presented opposite the display of postcards. The piece depicts an idyllic mountain town that, with each turn of the page, becomes slowly consumed by the landscape as the houses are destroyed one by one in various natural disasters. The last page of the book sees the final house being replaced by an apartment complex. Biernoff uses humour and play to expose not only nature’s destructive potential, but also humanity’s own insidious penchant for destruction and domination. Long Story Short speaks to humankind’s vulnerability in the face of the elements, as well as our stubborn and often violent resilience. By removing human figures from the scenery, we are left with a very distant and almost ambiguous impression of ourselves in the landscape, which lends to Biernoff’s dark and sweet sense of humour, an element of her work that often compels a second look. The book is a passing glance at humanity’s constant struggle to be both a part of and apart from our environment.

Elisheva Biernoff, They Were Here, 2009, (binoculars) acrylic latex and spray enamel on MDF and plywood. 67″ x 24″ x 24″. (painting) acrylic latex on birch plywood. 8′ x 16′ Image courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

The most commanding presence in the space is Biernoff’s They were here (2009), a large floor-to-ceiling mural with sculptural binoculars that sit in front. The mural depicts a stylized tropical seaside: it invites the viewer to look through the binocular lens before it. Anticipating a closer view of the mural behind, when we look through the lens we are instead confronted with the image of seemingly endless expanse of open water. Like the postcards, which command a sustained engagement, we come to realize that Biernoff’s seaside scene offers more information than first appears. A closer look reveals a volcano erupting in the background, a dead bird at the foot of a tree, a ship washed up on shore and the now-extinct passenger pigeon perched on a branch looking down at the viewer. The scene, when paired with the binocular sculpture, begs more questions than it answers. Are we looking beyond the island? Is this a premonition of what’s to come, or what has already happened? What else are we not seeing? They were here encourages the viewer to take a closer look at what is fabricated, what is real and how our perception of the world can be changed when we look or think more deeply. The scene allows the audience to fill in the blanks themselves, giving clues but no obvious answers.

In these ways, Biernoff’s work proposes an ambiguity much like that of our reality; we are uncertain of our future, especially in the context of an increasingly precarious natural world. In Without, within, we are offered a glance into another version of reality, one where things are not always as they appear and where we must reckon with both the power we are capable of having in life along with the precarity and impermanence of it. Without, within is a perhaps most poignantly a call to re-evaluate the uses of our power, and their oft-abusive realizations in the natural world. In Biernoff’s world, nature seems always to prevail, and indeed this is the case in our world too.

Emma Campbell holds a BFA in Painting and Drawing from Concordia University, Montreal, and is currently living and working in Banff, Alberta.