Elisha Masemann

Abstract:

The underlying premise of most urban art interventions is to challenge the functional use of urban space and disrupt the social relationships integral to public life. They materialise as an extensive range of ephemeral constructions, spontaneous installations and assemblages, and eccentric performances that challenge a “normative” organisation of city space. Artists, street artists and “pranksters” such as Banksy, Brad Downey, Jason Eppink and the artist collective, Performance, Video, Intervention, known as PVI, reveal wide-ranging methods for appropriating and reformatting aspects of the urban environment. This article proposes that examples of urban art intervention find consonance with the Deleuzian notions of breaking down the fixed and known into particles of the unknown from which a new “public” consciousness may emerge. The practice of art intervention is underscored by a determination to reveal to an unsuspecting public audience, insights into an unknown micro-universe that lies beyond the perceptible, rational, or understandable. They achieve this though a grass-roots style of interaction in which the city is exploited as both the site and medium for critique. The manifestations of art intervention in urban space are diverse and can thus serve to symbolically determine that there are ‘different ways of understanding, visualizing and materializing, molecular flows.’ In this sense, urban art interventions, as examples and/or instances of ‘the molecular,’ can be usefully framed as “agents of change” that operate or exist in order to subvert, resist and continually destabilize the tangible, fixed and known perceptions in public spaces. Although they are carried out surreptitiously and are a provocative and fleeting, these practices ‘create patterns and vibrations of flux, flow and process, melange and hybridity across borders and beneath surveillance’ representing a ‘positive force of freedom and change.’

In April 2006, a crumpled and misshapen telephone booth was anonymously dumped in a side street in London’s Westminster district. Bent at an awkward angle with a pickaxe protruding on one side, the phone booth appeared to have been the victim of an attack, and was bleeding red paint onto the pavement [Fig. 1]. The street art installation caused waves of confusion and amusement among onlookers, and generated interest from the media as reports of this unprecedented action spread. This, in turn, prompted a hasty public relations statement from British Telecommunications, the company responsible for the ‘welfare’ of phone booths. Significantly, as the drama unfolded and the unauthorized object was swiftly removed by authorities, the person(s) responsible remained anonymous. Interest lingered, however, about the motivation and identity of the artist responsible and the meaning behind the piece, though speculation had already prompted a chorus of conclusions from media about the underlying artistic statement.[1] The deliberate placement of the work in a district with heavy surveillance was, presumably, an integral part of the rebellious provocation. As a bold, public art statement, too, the work reiterated the redundancy of outmoded forms of telecommunications, paying homage to the ubiquitous telephone booth. It also heralded, perhaps, the ‘death of phone boxes’ in a decade where mobile technology has in many ways relinquished the function and practicality of these iconic British urban phenomena.

[Fig. 1] Banksy, Vandalised Phone Booth, 2006, Soho, London. Photograph by Nick Cunard.

The artist who later claimed authorship of the work, a famously anonymous British street artist known as Banksy, utilised an intervention strategy in an attempt to break down, or ‘molecularize,’ traditional, fixed, centralised institutions of power.[2] Examples of art intervention such as this, the subject of this article, share a commonality in their attempts to instigate a polyvocal response to city life. Their creative actions can be framed as attempts to generate a new consciousness – social, cultural, political, or other, through a series of challenges posed to macro systems of control. These include surveillance, law enforcement, media, advertising, and the rational and functional systems of power that ascribe a formulaic existence to urban experiences. Urban art interventions can thus be seen to correspond with micro-political forms in which systems and structures that connote rational and functional forms of control and knowledge are continually challenged or subverted. These spatial, relational and participatory art practices present oppositional responses to structured, top-down and authoritarian concepts of the city, and indeed, molar concepts to do with art and its display.

The molar versus molecular concept proposed by Deleuze and Guattari involves a series of particles that appear in variable states of production, of flux, of engagement or exchange, and of becoming or evolving.[3] Further, the ‘lines of flight’ that underscores Deleuze’s related notion, ‘absolute deterritorialization,’ in which phenomena are considered ‘unfolding bodies’ rather than ‘static essences,’ implies a perpetual state of change.[4] Thus conceived, ordinary, habitual states of being are continually fragmented, releasing ‘new powers in the capacities of those bodies to act and respond.’[5] In this précis, particles, energies, tangibles and intangibles collide and flow in unpredictable ways. It follows, then, that examples of urban art intervention, like Banksy’s Phone Booth, operate as molecular flows, and may be considered ‘agents of change.’ In effect, singularly or en masse, they operate as particles; as both positive and polemical forces; as signifiers and sites of transfer that produce unpredictable outcomes; as catalysts for breaking down and fragmenting congealed matter and blockages; and thus facilitating the flow and movement of various energies – urban, relational, social, and so on. Understanding a molecular layer of life or consciousness that encompasses these agents of change, and also the reactions caused by their existence, fusion and collisions, in addition, imbues these building blocks of life with qualities that are inherently political. For Deleuze, the ‘molecular sensibility’ is devolved in his ‘appreciation of microscopic things, in the tiny perceptions or inclinations that destabilise perception as a whole.’[6] Characterized by singularity, unpredictability and creativity on a micro scale, art interventions operating as molecular forces can consistently challenge taken-for-granted aspects of life in the form of pre-conceived perception, habitual responses, and notions pertaining to the traditional, fixed, hierarchical, authoritarian, and structured aggregates that exist on a macro, or molar, scale.

Taking this idea of molecular micro-politics and the introductory example, Banksy’s Phone Booth, as a point of departure, this discussion explores the art interventions carried out by a number of “agents.” These include Germany based artist Brad Downey, New York based Jason Eppink, and the PVI Collective from Perth, Australia. Generally speaking, the art interventions carried out by this group may be characterized as spontaneous, provocative, eccentric and often humorous or absurd. They comprise a series of spatial, relational and participatory art practices whose underlying synergy resonates with the contingent, unstructured and variable qualities of molecular exchange. On the surface they appear sporadically and unexpectedly, momentarily disrupting usual associations made between people and phenomena; their underlying objective, however, is to overturn the assumptions commonly made through their connection. Urban art intervention involves a further strategy in which artists seek to engage the city and its inhabitants in a dialogue. This is achieved through interruptions made to existing normative systems and relations in everyday city spaces – for example, by extending the legs of a park bench upwards to render it unusable; changing the language on signage or advertising; installing peculiar sculptural installations in unexpected places; recreating domestic spaces in public places; animating or reconfiguring existing public furniture; or instigating unlikely events and improvisations like a gallery opening on a subway platform. The city thus serves a dual purpose as both the site and medium for this type of artistic critique. It encompasses physical materials such as phone booths, park benches, rubbish receptacles, road signs and pavement stones, all of which have been appropriated for interventions. The city further comprises a series of latent coded networks, functional and commercial systems, from surveillance to transport to advertising, and the meta-language of road signage that can be disrupted to communicate alternative meanings. Finally, the city provides a direct interface between artist and spectator. Outside and away from galleries and exhibition spaces where art is usually viewed and experienced, urban art interventions materialize, usually unpredictably and often without legal endorsement, and encourage audiences to respond to unfamiliar art forms in everyday spaces.

The range of styles and media employed for urban art intervention is diverse, incorporating sculpture, object-based installations, digital media, individual events or happenings, pranks and performances. The following series of examples demonstrates the multiplicity of forms in which an intervention strategy has materialized. Polish street artist, Olek, has knitted ‘garments’ for existing street sculpture exemplified by Crocheted Charging Bull in which the iconic sculpture by Arturo di Modica received an oversized camouflage-style ‘sweater.’ Canadian street artist, Roadsworth, has altered the lines on a pedestrian crossing to form a giant footprint as a statement about carbon emissions in North America. British urban designer Bruno Taylor has installed swings at various bus shelters in London in a bid to establish spaces for play in the city. Swedish street artist, Akay, has constructed a quintessential Swedish country cottage on a traffic island in the centre of Stockholm, Traffic Island (2003-06) [Fig. 2], that remained in situ for three years owing to its popularity with the city’s inhabitants.[7] And finally, Spanish street artist, SpY, has created fleeting arrangements in public spaces such as a perfectly concentric circle from a pile of autumnal leaves lying on a basketball court. Whilst these examples represent a small fraction of interventions that have taken place during the last decade, they demonstrate wide-ranging engagement within various global city spaces in outwardly irrational, unpredictable and individual ways. Through the subversion of ubiquitous aspects of public furniture and signage, they potentially open up avenues to reconsider systems and structures on a micro-political level through a process of resistance and destabilization.

Click here for Akay Image [Fig 2.]

For Berlin-based American artist Brad Downey, the process of resistance and destabilization, in his own words, is about ‘shifting meaning.’[8] The influences that inform Downey’s practice (from skateboarding to graffiti) are wide-ranging, as are the manifestations, referential terms and his working methods. Ultimately, however, his work is underscored by a strategy that serves to surprise and momentarily disarm the observant passer-by. The artist sources or “borrows” materials such as paving stones, road cones and pedestrian lights directly from the structural urban environment, and reconfigures their functional messages before installing them back into the urban spaces from which they were removed. This process undermines, firstly, the authoritarian laws of the city that would normally determine such actions to be illegal; the meaning of the objects – usually road signs that direct the movements and flows of people and traffic through public space; the functional aspect of the object he is dealing with; and overturns the expected and rational spaces for the reception of art by intervening in public space and presenting art readied for unexpected encounter. Behind this unconventional working method, a tension alternates between the ‘legal’ and ‘illegal,’ the ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable,’ the ‘predictable’ and ‘unpredictable’ qualities of his art. Where one might conclude that they are gratuitous spectacles that unleash a wave of small-scale nuisances for the city’s pedestrians, on a molecular level, they generate a new consciousness that concerns the systems, structures, rational and functional regulations that govern urban spaces.

Downey’s interventions usually begin through a peripatetic ritual in which urban spaces generate a psychological effect on his embodied presence, thus determining his interaction with the city. During the period 2003-04, for example, Downey combed the streets of London for inspiration. In one “fortuitous” experience, he discovered a road sign “graveyard” where damaged road signs were deposited. Working with a co-conspirator, Downey proceeded to “borrow” a number of misshapen pedestrian poles, which they reconfigured in a nearby workshop before redeploying them in various London urban locations. The resulting installations, The Break Up [Fig. 3] and Endless Column in Context [Fig. 4] utilised a series of Belisha beacons, quintessentially British road signage that populates pedestrian zones around England’s major cities.[9] For Break Up the beacon was split directly in two and welded to two separate metal plates and drilled into the pavement, while in Endless Column, six additional globes were stacked in a vertical arrangement and wired together so as to light them all. Together these works capture a grass-roots style of micro-resistance borne out in urban art interventions. Both conceptually and physically, Break Up denotes a division or ‘breaking up’ of structures or distinct parts from which one might habitually draw a certain perception or “normative” meaning – that is, the stark combination of black and white coupled with flashing yellow light to signify a potential “hazard area.” With division, multiplicity follows as the molecular body initiates a breaking up or open, to create new, alternative flows of meaning. The multiplicity of globes that appear in Endless Column, then, can symbolize the multiplicity of forms or the permutations activated by such an event that consequently subverts the normative meaning of the Belisha beacon, thus forging new patterns and vibrations in the layer of consciousness. The moment of encounter takes on a new direction as alternative meanings are generated in and about urban spaces, its systems, structure and aspects relating to control.

[Fig. 3] Brad Downey, The Break Up, 2004, belisha beacon, anchor bolts, steel, paint. Duration 3 weeks. Image courtesy Brad Downey.

[Fig. 4] Brad Downey, Endless Column in Context, 2005, London, belisha beacon, plastic balls, screws. Duration 3 days.

Image courtesy Brad Downey.

The Belisha Beacon series orchestrated a dialogue with a public audience that, like Banksy’s Phone Booth, went beyond the initial encounter between artist and the city. Endless Column generated discussion on the BBC radio network that in turn amplified the minoritarian politics involved in art intervention. The BBC covered the installation as part of a show, “All Things Odd in London.” The ‘oddity,’ as it was labelled was deemed to be ‘seemingly too well crafted and smartly innocuous to be some kind shock value prank’ by the show’s host, Robert Elms.[10] The ensuing radio discussion queried whether the intervention was council approved, a bona fide artwork, a social protest (given its close proximity to London University), or a straightforward prank. In other words, the anomaly it presented prompted new ideas about odd ephemera in urban space. Moreover it confirms that the lines of flight that result from art interventions can encourage a multilingual approach to determining what art – social, participatory, relational, and its reception, entails.

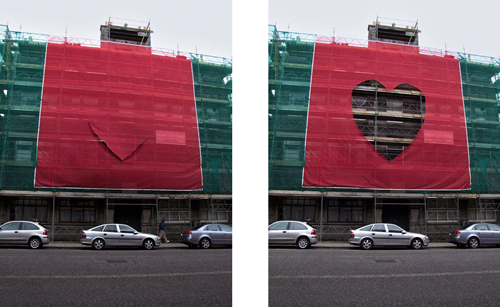

Downey’s interventions have begun to be discussed, photographed and celebrated by urban artists and fans of “outsider” art practices such as street art. This has necessitated that the artist bridge a “peripheral” presence as a street artist working illegally in the eyes of law enforcement, and a studio practice as an artist who regularly exhibits in solo and group shows from London and Berlin to Dubai. The division between the two, however, is often difficult to delineate and demonstrates the uneasy transition between a free critique of the city and one that is channelled through gallery representation. Deterritorialization and ‘lines of flight,’ as highlighted by Downey’s Belisha beacons, demonstrates the freeing up of ‘fixed relations’ as ‘flows of code’ are ‘exposed to new organisations.’[11] A further layer of complexity, and possibly an uneasy reterritorialization relating to molar concepts of art, thus arises when Downey is invited to provoke audience responses using an intervention strategy that is channelled vis-a-vis gallery sponsorship. For a group show, Adaptation: Redesigning the Everyday (2007) in Aberdeen, the artist was invited to complete a street art piece that demonstrated a response to design in everyday life. Downey’s contribution was to scale a four-storey high piece of scaffolding attached to a central city facade, and remove a fifteen metre high heart shape from the safety netting, unbeknownst to the curators of the show. The execution, retrospectively titled, Ladder Stick-Up [Figs. 5-6] created a minor stir with local media and mildly disgruntled project manager. However it was well received by the general public. Following Downey’s initial arrest, the gallery paid to have the safety netting replaced and the infringement cost. Therefore, whilst art intervention practices can be seen to be channelled (reterritorialized) from the street back into the gallery framework, echoing, perhaps, Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘axiomatic of capitalism,’ the transition is an uneasy one and a certain “in-between” or “gray” area results.[12] As agents of change operate freely in the street on a micro-political level, creating unordered and eccentric interventions, the regulatory constraint placed upon them as they enter institutional areas potentially jeopardizes their immediacy and effect.

[Fig. 5-6] Brad Downey, Ladder Stick-Up, 2007, Aberdeen. In progress and completed. Images courtesy Brad Downey.

Whilst Downey’s urban intervention practice revolves around a philosophy of ‘shifting meaning,’ New York-based Jason Eppink enacts a different series of self-styled Unauthorized Happenings in his native city and across the United States. These are designed to offer ‘prototype solutions’ – intuitive responses to the urban environment and spontaneous interactions in public space based on relational and participative foundations. Eppink refers to himself (on his website) as A Dude Who Is Just Trying To Make Things A Little Better. New York doubles as the medium and canvas, or playground, where he instigates humorous, often absurd, non-confrontational situations that highlight latent systems of control in public space. These include commercial advertising, environment issues and surveillance, or sometimes, a response to a simple lack of seating in a subway station. In each case Eppink responds with a socio-cultural and politicised critique through interventions methods. These also highlight ‘invisible geographies,’ a phrase introduced by George Yúdice to current discussions on art intervention.[13] Yúdice’s phrase refers to the underlying potential of art intervention methodology to generate spaces for ‘unpredictable exchange’ that highlight the ironies associated with modernity such as systems of capital production and depreciation, disadvantage and inequality, and consequently to encourage a new consciousness about these through ‘new cultural articulations’ and manifestations of ‘cultural capital’ in urban space.[14]

Eppink’s ‘new cultural articulations’ include ‘prototype solutions’ designed to combat the ‘consumerist imperatives’ channelled through advertising in the New York subway environment. One such example, Pixelator (2007 ongoing), is an ‘anonymous collaboration’ between himself and New York’s Metro Transit Authority (MTA) in which Eppink temporarily commandeers one of eighty dedicated advertising LED screens positioned at subway entrances.[15] Eppink appropriates this space using made-to-measure Styrofoam boards, frosted diffusion gel and a light filter that transforms the plane of the screen into pixelated tiles of colored light [Figs. 7-8]. This method of intervention in the passive subject-consumer ‘spectacle’ resonates with Situationist techniques of détournement espoused by Guy Debord in the 1960s. Today it is also commonly referred to as culture jamming or sub-vertising. Mark Dery envisions culture jamming as ‘an engaged politics’ in ‘an empire of signs,’ or, as Tim Cresswell paraphrases, ‘a form of semiological guerrilla warfare’ as first proposed by Umberto Eco in 1967.[16] Originally employed as a method for altering billboards, culture jamming now encompasses the general hijacking and diversion of any signifiers of mass media towards ‘radically different intent.’[17] As a multi-coded space where multitudes of pedestrians and mass-cultural interests converge (on a macro or molar scale), the New York subway has long played host to a multitude of culture jamming practices. These include Keith Haring’s appropriation of advertising niches for his characteristic ephemeral chalk drawings in the early 1980s, Joseph Beuys’ social sculpture, Creativity=Capital (1983), and Alfredo Jaar’s subversion of a CBS News advertising campaign, You and Us (1984).[18]

[Fig. 7] Jason Eppink, Pixelator, 2007, foamboard, diffusion gel, duct tape. Installation shot from Union Square intervention.

Image courtesy Jason Eppink.

![]()

[Fig. 8] Jason Eppink, Pixelator, 2007, foamboard, diffusion gel, duct tape. Installation shot. Image courtesy Jason Eppink.

By exploiting the molar concepts aligned with advertising, these campaigns, like Eppink’s contemporary version, have attempted to molecularize and free up fixed relations and perceptions concerning the use of the subway environment. On a micro-political level, Eppink demonstrates alternative messages about urban space, using the latent signs and systems within it as both the target and medium for his critique. Hal Foster has previously observed similar dyadic relations between artists and sign systems, for example, in the work of Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer and Krzysztof Wodiczko working with ‘subversive signs’ in the mid-1980s. Foster writes, ‘Each treats the public space, social representation or artistic language in which he or she intervenes as both a target and a weapon. This shift in practice entails a shift in position: the artist becomes a manipulator of signs more than a producer of art objects.’[19] As part of this complexity, too, the viewer of such artistic language becomes ‘an active reader of messages rather than a passive contemplator of the aesthetic or consumer of the spectacle.’[20]

Eppink’s critique of the spectacle can be further understood in light of Jean Baudrillard’s The Ecstasy of Communication (1987), in which he argued that advertising, ‘is our only architecture today,’ materialising as the ‘omnipresent visibility of enterprise brands, social interlocutors and the social virtues of communication.’[21] And further that it ‘invades everything, as public space (the street, monument, market scene) disappears.’[22] Eppink’s Pixelator echoes this sentiment; he states,

While the MTA’s efforts to create more opportunities for video art exhibitions in public spaces is to be commended, selected works remain wholly fixed on commercial goods and media conglomerate events, a short-sighted curatorial choice that regrettably ignores the full potential of these promising exhibition spaces.[23]

This tongue-in-cheek statement defends his creative misuse of the advertising spaces whose messages he “jams” and underscores the need for the collaboration with MTA to remain anonymous. The intervention thus serves to appropriate, deviate, fragment, provoke and disrupt, establishing multi-dimensionality and a polyvocal response to the coded, top-down organisation of public space. Eppink’s prototype solutions reinvigorate these spaces through improvised, non-rational and non-functional interventions that double as socially motivated art gestures.

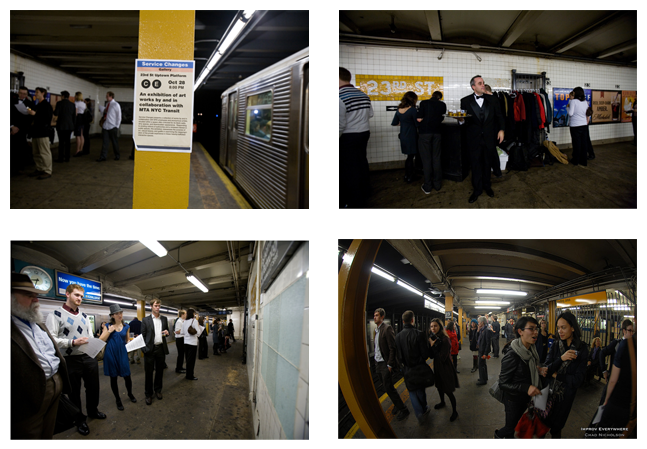

In another collaborative effort in the New York subway, Eppink and non-profit organisation, Improv Everywhere, have instigated a Subway Art Gallery Opening in a crowded subway space [Figs. 9-12]. The subway station on the 23rd St Uptown Platform played host to an improvised gallery event, complete with the trappings of an exhibition opening – a coat rack, a cellist, a wine waiter and guest book, that framed routine objects, utilities and fleeting personas of the subway environment as objet d’art. Highlighted among the objects requisitioned for the event were public telephones, storm water grates, rubbish receptacles, brick walls and tiles. Further temporal “performances” were proposed in works such as, Woman Sitting on a Bench, an artwork that framed the weary commuter in a composition that balanced ‘the ambulant’ and ‘the recumbent,’ implicating ‘the tension between repose and the exigencies of train arrival.’[24] Elsewhere in the vicinity wall placards accompanied more tangible elements such a rubbish receptacles (titled Repository, 2005, no 289 in a series of 2,000). The Repository was nuanced with a ‘subtle yet insistent timbre’ inspired by permanent art installations.

(Left to right) [Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12] Jason Eppink and Improv Everywhere, Subway Art Gallery Opening, 2008. Installation and performance intervention. Images courtesy Chad Nicholson and Katie Sokoler.

As a participative, relational and socially engaged art intervention, Gallery Opening highlights the innumerable possibilities for collaboration and unpredictable art encounter in the subway environment. It also celebrates the ‘counter-spectacle’ in relation to usual and accepted spaces for viewing and appreciating art, recalling in various ways the anti-art-establishment attitudes that underscored Fluxus tours of kerb sides and public toilets in New York; or Ben Vautier’s Art Total Fluxus event in 1963 that attempted to collapse the barriers between art and life; or Hi Red Centre’s Street Cleaning Event in Tokyo (1964) in which futility teemed with humor and parody, became the leading ‘edge’ for social and political critique. In this case, Eppink’s opening took place in the vicinity of New York’s high-end gallery district of SoHo, making it more relevant to its urban surroundings and commenting on the exclusivity of gallery spaces, and indeed molar concepts relating to the exhibition and display of art in commercial and institutionalized spaces. The opening highlights Eppink’s underlying philosophy that through re-examining mundane objects encountered in everyday spaces, and by revisiting their functionality, observers are encouraged to reconsider their relationship with their surroundings. Through this process he suggests that it is possible to find new, useful contexts in which to engage with these phenomena.

For the vanguard artist collective known as PVI (Performance, Video, Intervention), the discussion turns to a politically inspired form of ‘tactical media’ and performance-based interventions that seek to engage mostly Australian audiences in a dialogue about authority, control and surveillance in public space. Outwardly PVI’s interventions appear as eccentric spectacles or absurd performances. Yet significantly, too, the activities of this group are channelled through gallery commissions in Australia – Perth, Sydney and Brisbane, and abroad in Taipei, Singapore and Santiago. Many of these instigate symbolic acts of resistance that are informed by political theory and literature. The group claims to be significantly influenced by the anonymously published L’insurrection Qui Vent (The Coming Insurrection), for example, and John Holloway’s Crack Capitalism (2010), which focuses on small-scale resistance operations, or ‘cracks’ overrun by forces of capitalism in the forms of security, policing and intrusive surveillance. Notably, PVI utilize the gallery platform to engage audiences in micro-political interventions in which participatory and relational-style aesthetics play a major role, thus signalling further complexity in relation to the deterritorialization and reterritorialization of urban interventions as they fluctuate in-and-out of various cultural spheres and flows of code.

The PVI collective have rigorously analyzed the state of surveillance and personal privacy, for example, in Australian urban spaces through a thematic performance intervention, Panopticon [Fig. 13]. This intervention has been activated in a range of major Australian cities including Brisbane and Sydney (as part of Primavera 04) where systematic surveillance appeared to stipulate an organization of space based on ‘appropriate behaviour.’ Taking as its reference Foucault’s seminal essay, Panopticism, the PVI intervention explores the boundaries of conditioned social behaviour and how this impedes individuality and creative freedom. The intervention comprises an ‘umbrella cocoon’ – a spherical assemblage of opened and interlocking umbrellas that overlap and envelop the upper torso of a passenger. The objective is to conceal and protect the identity of the passenger as they are guided through public spaces to carry out everyday activities such as posting a letter, getting to work, or catching a ferry. The outwardly eccentric “privacy service” was indeed designed to explore the acceptability of unconventional acts in public space in which the identity and trajectory of the participant is unknown. This relates in turn to Foucault’s synopsis of Jeremy Bentham’s circular prison structure at one time designed to ensure the ‘automatic functioning of power’ through a system of permanent visibility: ‘The panoptic mechanism arranges spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and to recognize immediately.’[25] The Panopticon intervention in Sydney, for example, brings Foucault’s theory into a contemporary focus. It confirms his assertion that ‘surveillance is based on a system of permanent registration’ that functions alongside hierarchy, structure, observation and code as part of a utopian vision of ‘the perfectly governed city.’[26]

![]()

[Fig. 13] PVI Collective, Panopticon, 2004, Brisbane, black umbrellas. Performance intervention.

The metaphorical and conceptual use of a ‘ubiquitous’ object – the umbrella, adds a complexity to the challenge of latent systems of surveillance in public space. Primavera curator, Vivienne Webb, explains,

The lateral, even dysfunctional re-use of the ubiquitous umbrella … posits old technology against new, as well as the individual against the system. Instead of protection from the natural elements, the umbrella is utilised as a barrier against invasive technology. Patently inadequate to the task, its key failure poetically highlights the extensive use of technologies of control within our public spaces, while simultaneously demonstrating both the vulnerability of the individual and their capacity for resistance.[27]

In Sydney, PVI encountered resistance as they guided their passengers across open public spaces near the Sydney Opera House, confirming this ‘patent inadequacy.’ During several journeys such as David goes to Work, security rangers requested permits and issued warnings regarding filming. They further deemed the umbrella spokes a public safety hazard and extra security was thus called upon to monitor the crossing of the open space. These setbacks to the journey, in effect, highlighted the success of the operation. Kelli McCluskey explains, ‘Its failure to succeed in what was a basic everyday task highlighted the issue of surveillance, security and access to what is deemed to be appropriate behaviour in public spaces.’[28]

The peculiar outward appearance of Panopticon is reminiscent of eccentric performance and conceptual art gestures like Valie Export’s provocative Touch Cinema (1968-71) and Adrian Piper’s Catalysis series of works in the early 1970s that confronted audiences with confrontational guises and gender-based body-centric interventions in public spaces. Export and Piper have explored embodied spaces, engaging critically with individual, sexual and cultural references and the ambiguous position of the female body, in particular, as both sign and symbol. With its focus on surveillance systems, too, Panopticon finds consonance with Francis Alӱs’ more recent series of Seven Walks in London (2004), particularly the experimental performance, Guards. Alӱs’ enlisted a regiment of Coldstream guards, whose exterior appearance ordinarily connotes order, authority, elitism and historic tradition in the service of the British monarchy. These guards he purposely displaced, instructing them to disperse throughout the Square Mile of London, walking different paths and thus articulating an unregulated presence, and possibly anarchy in the absence of visual, symbolic order. The performance was captured on CCTV cameras, in addition, that highlighted the all-seeing panoptic eye that monitors movements and activities in embodied spaces, as with PVI’s Panopticon.

Since the Panopticon interventions in the mid-2000s, PVI’s focus has turned to interventions that incorporate gallery audiences as they set out alternative ways to negotiate the city and its spaces. Deviator (2013) proposes a more playful approach to subverting social norms and utilizes mobile technology as a platform to mobilize participating audiences; it is designed to challenge audience-participants to carry out spontaneous acts of their own in urban spaces. The intervention attempts to blend ‘radically altered versions of childrens’ games with subtle live performance, placing audiences as interventionists out on the streets, ready to creatively disrupt the city, one game at a time. [sic]’[29] Generally speaking Deviator proposes that the city is a giant board game and invites participants to rediscover childlike explorations, play, interaction and movement, receiving points for activities carried out. In the process, participants are actively engaged in a process that conceptualizes new ways for experiencing urban space, opening up and exposing a new layer of consciousness that is channelled through relational and participatory methods. Underlying this outwardly playful theme, however, as the title suggests, a notion of deviation from social and cultural norms, habits and responses, is sustained. Deviator thus ‘activates philosophies around revolution, positioning “games” as a potential trigger to alter the official narratives of place.’[30]

[Fig. 14] PVI Collective, Deviator, 2013. Performance and ‘tactical media’ intervention.

The mobile technology adapted for Deviator includes a custom-designed phone application that gives each user access to an onscreen map from where they can select game locations around the city. Inbuilt scanning technology on android and iPhones allows the user to activate a QR code at the game site to upload instructions for each playful interlude. These include jumping across an intersection in a hessian sack (like in a children’s ‘potato sack’ race) [Fig. 12]; leaving an anonymous speech act on a public park bench; participating in a game of ‘ring-a-rosy’ or ‘twister’; and using green spaces for chipping a coffee cup into a rubbish receptacle using a golf club. There are fifteen sets of instructions in total, each awarding points for difficulty and range of activities activated by the user.

As with Panopticon and other interventions performed by PVI, Deviator is underscored by a micro-politics that is associated with a grass-roots style of resistance. However, the intervention seems to explore more successfully the psychological effects of public space on individuals, and further aspects of playful drift through urban space (recalling Debord’s notion of dérive) come through as inherently more palpable themes than impending’ insurrections,’ which PVI cite as an underlying political motivation. Nevertheless attempting to challenge latent rational and functional aspects of public space holds the potential for political, individual, and molecular agitation, instigating or at least proposing an alternative method for creative, relational, social and participative engagement. Bearing in mind that the situationist concepts of derive and psychogeography were designed to collapse the social and structural hierarchies present in public space, and to oppose the rationalism principles that they (following Lefebvre) believed had instigated an over-simplified division of society, the spontaneous and explorative nature of Deviator conceivably brings these situationist concepts into a contemporary ‘post-situationist’ intervention format.

It is perhaps practical to speculate, on a final note, that utilising the mobile platform in Deviator, a costly endeavour in terms of the application development, would not be feasible without the gallery institution of festival framework that funds PVI’s projects. In turn there is perceivably an exchange between Deleuzian concepts of deterritorialization and reterritorialization whereby interventions that often begin outside the gallery framework – including Downey’s Belisha beacon series, Eppink’s Pixelator series, return to the gallery as a point of reference, or, at least a symbolic place where boundary-pushing avant-garde practices such as these, are incubated and disseminated to gallery audiences. Ultimately, the galleries behind PVI appear to profile their urban interventions ‘as art,’ keeping them within the greater rubric of contemporary art movements. And it is this, perhaps, that allows them to maintain a certain artistic integrity that is in turn supported by continual gallery commissions and sustained audience interest.

Urban art interventions have materialized as a strategy in art movements and cultural milieus throughout the latter twentieth century and early twenty-first centuries. Twenty years ago, Krzysztof Wodiczko queried how an ‘aesthetic practice’ in urban space could instigate a ‘critical discourse between inhabitants themselves and the environment.’[31] Around the same time Hal Foster was commenting on the link between ‘public spaces, social representation,’ and ‘artistic language’ in the work of Kruger, Holzer and Wodiczko, among others, whose leading concerns appeared in the manipulation of the latent signs and messages in urban spaces. Today a range of artists – Brad Downey, Jason Eppink and the PVI collective among them, are contributing to a critical discourse that in a sense continues Wodiczko’s so-called ‘struggle for public life.’ Downey, Eppink and the PVI collective treat the city as a medium, employing diverse tactics to appropriate and subvert its rational and functional uses, and responding to systems of order through eccentric and unpredictable forms of critique. Like Banksy’s Phone Booth that opened this discussion, the urban interventions by these artists provoke reaction, ranging from the public who encounters them, to media, law enforcement and city administration. They continually flux between authorized and unauthorized spheres of art, as well as considerations of inside, or “legitimate,” and outsider art, as opposed to gallery spaces for exhibiting art. Wherever they are found or encountered, contemporary forms of urban art intervention continue to introduce irrational, individual, contingent, unstructured and unpredictable aspects to the city fabric, to offer a ‘prototype solution’; to encourage different ways of experiencing urban space; to generate participation and social interaction; to ‘shift meaning’ or simply ‘to respond to the world around us,’ as PVI have stated. Art interventions such as these will undoubtedly continue to challenge our perceptions of the habitual uses and micro-political misuses for city space. The diversity and challenge they pose as ‘agents of change,’ on a molecular scale and in response to existing molar aggregates, can potentially yield productive ways for understanding contemporary urban spaces. For these agents, the city comprises sites for numerous forms of aesthetic, relational, participatory, social and creative exchange, and perhaps the resources for healing the ‘body politic’ through new layers of consciousness that are brought to light in urban space.

Bibliography

“Artist’s cold call cuts off phone,” BBC News, accessed July 11, 2012. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4887660.stm.

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Ecstasy of Communication” in Hal Foster (ed). The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Washington: Bay Press, 1983, 126-134.

Bishop, Claire, ed. Documents of Contemporary Art: Participation. Cambridge, Mass.; London: Whitechapel, The MIT press, 2006.

Bourriaud, Nicholas. Esthétique Relationelle. Dijon: Les presses de reel, 1998.

Costello, Diarmuid and Jonathan Vickery, eds. Art: Key Contemporary Thinkers. Oxford; New York: Berg, 2007.

Cresswell, Tim. “Night Discourse: Producing/Consuming Meaning on the Street” in Nicholas R. Fyfe, ed. Images of the Street: Planning, Identity and Control in Public Space, London: Routledge, 1998.

Eppink, Jason, “Jason Eppink’s Catalogue of Creative Triumphs”: www.jasoneppink.com

Fitzpatrick, Tracy. Art in the Subway: New York Underground, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Foster, Hal. Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics, Seattle: Bay Press, 1985.

Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism,” in Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall, Visual Culture: A Reader, London: Sage, 2008, 61-71. Originally published in Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, London: Penguin, 1977, 195-228.

Klanten, Robert and Matthias Huebner, eds. Urban Interventions: Personal Projects in Public Places. Berlin: Gestalten, 2010.

Nguyen, Patrick and Stuart Mackenzie (eds.). Beyond the Street; The 100 leading Fugures in Urban Art (Berlin: Gestalten, 2010),

Parr, Adrian (ed). The Deleuze Dictionary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005.

PVI Collective, website: www.pvicollective.com

PVI Collective – Panopticon: Sydney,’ Filter, no 58 (2004)

Wodiczko, Krzysztof. “Projections” Perspecta 26: Theatre, Theatricality and Architecture, 1990.

Yúdice, George. “The Heuristics of Contemporary Urban Art Interventions.” Public 32 (2005), 8-21.

Zipco, Ed, Reid, Leon IV and Brad Downey (eds.). The Adventures of Darius and Downey, New York: Thames and Hudson, 2008.

[1] A BBC article, “Artist’s cold call cuts off phone,” quoted a British Telecommunications spokesperson who claimed, ‘This is a stunning visual comment on BT’s transformation from an old-fashioned telecommunications company into a modern communications services provider.’ ‘Artist’s cold call cuts off phone.’ BBC News, accessed July 11, 2012. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4887660.stm.

[2] The sculptural installation signalled a dynamic shift in Banksy’s street art oeuvre to date. The enigmatic artist, who has been dubbed the ‘Gauguin of Graffiti’ owing to his meteoric rise in popularity and notoriety in spite of his sustained anonymity, is best known for his irreverent, darkly humorous stencil work. This format has been utilised to deliver his signature style of biting social comment on the two-dimensional wall surfaces in cities across the United Kingdom and the United States.

[3] Tom Conley. “Molar” and “Molecular,” in Parr, Adrian (ed). The Deleuze Dictionary (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 175-177, 177-178.

[4] Tamsin Lorraine. “Lines of Flight,” in Parr, 2005, 147-148. This notion has in turn been particularly influential on the formulation of Nicholas Bourriaud’s ‘relational aesthetics.’ Claire Bishop identifies, ‘Bourriaud takes from Guattari the idea that the work of art is, like subjectivity, a process of becoming: it is a collectively produced and open-ended flux that resists fixity and closure.’ This idea incorporates the reception of art by an audience as basis for relational interactivity. Aspects relating to this are incorporated here, though without the specific application of Bourriaud’s theory. Claire Bishop cited in Costello, Diarmuid and Jonathan Vickery (eds.). Art: Key Contemporary Thinkers (Oxford; New York: Berg, 2007), 50.

[5] Lorraine, “Lines of Flight,” in Parr, 2005, 147.

[6] Tom Crowley, “Molecular,” 178. Thus, as Crowley summarises, ‘molecularity is tied to a micropolitics of perception, affect, and even errant conversation.’

[7] The traditional Swedish summer cottage was completed by accoutrements such as a washing line, letterbox and a guest book that recorded the nostalgic sentiments of the many urban visitors who trekked across the highways to spend time there. The images are displayed on the artist’s dedicated website, Akayism.org.

[8] Nguyen, Patrick and Stuart Mackenzie (eds.). Beyond the Street; The 100 leading Fugures in Urban Art (Berlin: Gestalten, 2010), 335.

[9] These black and white striped poles topped with globular amber-coloured lights distinguish pedestrian zones in London and are normally found next to “zebra crossings.”

[10] Robert Elms quoted in Zipco, Ed, Reid, Leon IV and Brad Downey (eds.). The Adventures of Darius and Downey (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2008), 223. The radio segment gave the opportunity for members of the public, including the ‘prankster’ responsible, to phone in and discuss the piece. Downey attempted to phone in to discuss the piece, however was dismissed for, ironically, revealing too much knowledge about the installation.

[11] Parr, Adrian.“Deterritorialisation / Reterritorialisation.” In Parr, 2005, 69.

[12] A similar situation has arisen where public stencil works by Banksy have become collectable items with a significant resale value on the secondary market, leading to the removal of parts of city walls and a relative upsurge in property prices for buildings that have been targeted by Banksy. This development is also driving the rise of ‘urban art’ galleries that specialise in the commercial resale of “legal” street artworks and has prompted some street art observers to accuse others of ‘selling out.’ The irony of this position is not lost on many of the artists, Banksy included. For a major exhibition on street art at MOCA Los Angeles, Banksy created a large graffiti installation that included graffiti-covered panels shaped into a large cathedral-style window with an identifiable male ‘tagger’ kneeling in prayer beneath it. Nearby, the stencil of a dog making its mark on a faux street wall, confirmed two different viewpoints of the art practice. That is, on one hand these practices are deemed to be nuisances and the pastime of youth needing to ‘make their mark,’ while on the other, they are given hallowed status by their inclusion into major exhibition programmes.

[13] Yúdice, George. “The Heuristics of Contemporary Urban Art Interventions.” Public 32 (2005), 8-21. This essay was published in an edition of Public devoted to Urban Interventions. Yúdice’s was also keynote speaker at a symposium on art intervention, The Visible City (Toronto, 2005) published concurrently with the issue.

[14] Ibid. 14. Note 1 (author’s emphasis). Yúdice makes reference to art interventions carried out in the context of Arte Cicade and inSITE for which artists including Alfredo Jaar have critically explored the transnational labour/intellectual economy between the US and Mexico using art intervention strategies.

[15] Jason Eppink’s Catalogue of Creative Triumphs, www.jasoneppink.com showcases his range of prototype solutions, unauthorized happenings and various other projects.

[16] Dery, Mark. Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing and Sniping in the Empire of Signs (Westfield, NJ: Open Media, 1993), 6. Cited in Tim Cresswell. “Night Discourse: Producing/Consuming Meaning on the Street” in Nicholas R. Fyfe (ed.). Images of the Street: Planning, Identity and Control in Public Space (London: Routledge, 1998), 268-279.

[18] Jaar seamlessly transposed the slogan on placards in advertising niches in subway cars for a CBS News campaign by exchanging the heading, ‘If it concerns you, it concerns us’ with ‘If it concerns us, it concerns you.’ See Fitzpatrick, Tracy. Art in the Subway: New York Underground (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 220.

[19] Foster, Hal. Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics (Seattle: Bay Press, 1985), 100.

[21] Baudrillard, Jean. “The Ecstasy of Communication” in Hal Foster (ed). The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture (Washington: Bay Press, 1983), 126-134.

[23] Jason Eppink’s Catalogue of Creative Triumphs, accessed online 1 October 2013, www.jasoneppink.com

[24] Jason Eppink’s Catalogue of Creative Triumphs includes all 28 placards produced for the event: http://jasoneppink.com/subway-art-gallery-opening/. Accessed October 1, 2013.

[25] Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism,” in Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall, Visual Culture: A Reader (London: Sage, 2008), 61-71. Originally published in Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (London: Penguin, 1977), 195-228.

[27] PVI Collective Ltd. “Panopticon,” Vivienne Webb quoted, accessed June 7, 2012. http://www.pvicollective.com/art/panopticon.asp.

[28] ‘PVI Collective – Panopticon: Sydney,’ Filter, no 58 (2004), accessed June 7, 2012. http://filter.org.au/issue-58/pvi-collective-panopticon-sydney-2/#more-3809. Despite gallery endorsement, two ‘plain clothes’ federal government officers closely followed the PVI team back to the gallery at the close of the journey. They told the members of the collective, in no uncertain terms, that if they ventured out again with the Panopticon ‘contraption,’ and AUD 4,000 fine would be imposed on them.

[29] PVI Collective Ltd, “Deviator,” accessed June 12, 2012, http://www.pvicollective.com/art/deviator.asp.

[31] Wodiczko, Krzysztof. “Projections” Perspecta 26: Theatre, Theatricality and Architecture (1990): 273-287. In a renowned example from 1984, Wodiczko surreptitiously projected a swastika symbol onto the pediment facade of the South African embassy in London that became an enduring talking point despite only lasting two hours in situ. Wodiczko’s aesthetic practices, in particular, so conceived, were accompanied by an urgent “call to arms” in which he called on other artists, activists and researchers, ‘interested in the struggle for public life,’ to respond critically to developments in urban spaces and create ‘alternative, aesthetic structures and events.’

Elisha Masemann recently completed her Masters in Art History at the University of Auckland with first class honours. Her thesis, The City as a Medium: Art Interventions in Urban Space, explored intervention methods in art practices since the 1950s, connecting these with contemporary street art practices. Elisha is now embarking on PhD research into street art and the city.