Sarah Walko

Part I: The Sea

There was neither non-existence nor existence; there was neither the realme of space nor the sky, which is beyond. What stirred? Where? – The Rig Veda

The mantis shrimp is a marine crustacean with eyes that are considered to be one of the most complex in the animal kingdom. They have such advanced vision and incredibly colorful bodies that it is suggested their evolution of color vision has taken the same direction as the peacock’s tail. Their eyes are so remarkable that they can perceive multispectral images and polarized light. The eye itself consists of two flattened hemispheres separated by six parallel rows of specialized ommatidia, which divides the eye into three sections, allowing each eye to have trinocular vision. The ommatidia are arranged in four rows and each row carries sixteen photoreceptor pigments. Twelve of these are for color sensitivity and the rest are for filtering. In comparison, humans have only four visual pigments.

Their eyes help them to recognize different types of prey species, many of which are transparent or have shimmering scales. And because they hunt with rapid movements of their claws they need very accurate ranging information and depth perception. One thing this incredible vision reveals most profoundly is that there are a lot of colors that exist in the universe that we cannot even see or experience. These creatures see a different picture.

Mantis Shrimp. Photo by Nazir Amin. Image used with Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Plankton, also known as the ant of the sea, is another marine creature but one that is entirely microscopic. Plankton inhabit the pelagic zone of oceans, a subterranean world of dark water and nearly imperceptible movements, but one that is brimming with life. This region is very important as it provides the food supply for much aquatic life. They are one organism that does not belong to a specific kingdom. If an organism inhabits a marine pelagic zone and is unable to swim against the ocean current then it can be classified as planktonic (jellyfish, algae, and drifting plants). The name plankton is derived from the Greek word “planktos”, meaning “wanderer” or “drifter”. These small organisms, living in the darkest reaches of the water, help feed the world above them. Their view collapses planes into an intricate meshwork of species survival.

The sea is filled with fascinating microscopic worlds. It is also a metaphor that has filled literature, poetry, art and song across all cultures and time, both as symbol of freedom and one of mystery. Sometimes it is depicted as a calming influence, while other times dangerous and stormy. It is also a metaphor for the unconscious. Anais Nin once wrote, “I must be a mermaid… I have no fear of depths and a great fear of shallow living.” Like murky water below a surface, what we cannot see is less a barrier as it is an entrance. It is an underworld, which can be experienced by diving in. How can we know the sea of unseeable things and more importantly the ones that are affecting us? This question probes not just our environment but what lies below our skin and inside the bone walls of our skulls. Things happening around and within us at a molecular level affect how we think and act on fundamental levels, as well. Researchers, writers, philosophers and artists often turn away from the vast expanse of the limitless sky in a search for meaning or to find a way to make the invisible visible, looking into tiny underworlds, studying everything from the vision of crustaceans to brain chemicals, seeking night lights in the deep dark.

Part II: Entering With Language

Artist Jenny Holzer made a permanent site specific sculpture titled 715 molecules in 2011. The piece is a permanent sculpture within the science quadrangle on the campus of Williams College in Massachusetts. It is comprised of a sixteen feet long and four feet wide sandblasted diorite stone table and benches. Holzer collaborated with professors and students in the both the arts and sciences and covered the surface of the table with diagrams of chemical compounds of 715 different molecules.

Holzer is best known for her use of language as a way to stir and provoke audiences. The table, used by both the community and the college, is meant to be a place for dialogue, discussion and contemplation. Holzers’ interest in language caused her to ask how do scientists define the world around them? She began with the scientific tradition of using specific concrete language to represent complex concepts such as charts, graphs, and symbols. Despite what many know of her text-based work, this was not unknown territory for her. In the early years of her practice she used to reproduce physics diagrams out of textbooks by hand, taking in and studying this visual language number-by-number and line-by-line.

When Holzer approached this piece she wanted to use these diagrams to represent broad concepts such as love and emotion, pleasure and pain and other natural phenomena, through the language of molecular structures. She ended up calling the sandblasted engravings, “tattoos”. In it she included diverse examples, such as symbols for Ethanol, components of chocolate, DDT, Gypsy moth pheromones, and water as molecules. As the piece and the process of the piece evolved she kept adding more and began to think of it as constellations in the night sky. One of the points of contemplation Holzer was aiming for in this piece was to force us to confront how these chemicals affect us, define us and influence our behavior.

In August of 2013 scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology disclosed the “Mini Lisa”. The piece is a copy of the original hanging in the Louvre except – 25,000 times smaller. It is described as “just a third of the width of a human hair.” It is a nano-technique created by doctoral candidate Keith Carroll after someone bet him couldn’t be as precise as to replicate a mini version of a great work of art. The process he discovered that allowed him to prove them wrong, included heating a needle very precisely on an atomic force microscope that then produced various shades of grey in a particular dye. The piece he then produced proved the ability to manipulate molecular concentrations. Researchers wrote a paper on the technology, known as thermochemical nanolithography.

An exhibition took place in 2011 at the Centre des Arts in Enghien-les-Bains, France titled Invisible and Intangible, When Art Meets Nanoscience. Eight artists participated in the month long exhibition but their work on view was from a year-long project they were involved in and conceived by the OpenLab Project. For that entire year the artists worked closely with twenty scientists working in chemistry, surface science, material science, nanoscience, and physics from five different research laboratories in France, all of which specialized in nanomaterials science.

One project realized by artist Eduardo Kac was titled Aromapoetry. Kac was committed to developing a new form of poetry by using chemical and material science. He ended up tackling this task by working with the scientists to first synthesize and then make a mixture of odiferous molecules, so the resulting poem is actually a perfume. He decided then to make a book of poems. In order to do so, one of the lab partners developed an invisible nanosponge which is made from porous amorphous silica glass. They then binded the thin layer of porous glass that was 200 nanometers thick to each page of the book. The glass traps the smells and releases them very slowly. There would be no other way for the smells to be distinct and linger without this technology because the fragrances would quickly dissipate after a few days. Kac also made a set of small bottles as a part of the book so a viewer can replenish the pages over time if needed.

Kac approached the project like a poet, thinking of the poems as olfactory experiences and using chemical procedures to achieve the smell he desired. He was aware of the reader being is an active participant in poetry and involved in its interpretation. The final piece is the first book ever written exclusively with smells. There are twelve poems in total. Some are composed with only one or two molecules, while other involve dozens, so the poems in the book vary from quite simple to quite complex in their level of molecular intricacy. And while each poem is its own piece, Kac considered the whole flow the way a musician would consider it for an album – thinking about an overall rhythm to the entirety of the book.

Part III: To See

“The center of gravity has shifted. For the primitive hunting peoples of those remotest human millenniums when the saber tooth tiger, the mammoth, and the lesser presences of the animal kingdom were the primary manifestations of what was alien… the great human problem was the task of sharing the wilderness with these beings. Both the plant and the animal worlds, however, were in the end brought under social control. Where upon the great field of instructive wonder shifted… The descent of the occidental sciences from the heavens to the earth (from seventeenth century astronomy to nineteenth century biology) , and their concentration today, at last, on man himself (in twentieth century anthropology and psychology) mark the path of prodigious transfer of the focal points of human wonder. Man is the alien presence with whom the forces of egoism must come to terms, through whom the ego is to be crucified and resurrected, and in whose image society is to be reformed. Men, understood however, not as “I” but as “Thou”: for the ideals and temporal institutions of no tribe, race, continent, social class, or century, can be the measure of the inexhaustible and multifariously wonderful divine existence that is the life in all of us.”

– Joseph Campbell

Artist Christine Laquet recently completed two versions of a piece she titled “I See the Sea and the Sea Sees Me”. The first version of the project was a book. She explains:

(…) There are many Ways of Seeing; this book is an attempt to focus through other means than simply “through the eyes,” lending more space to the unknown, maybe in being under influence, giving more leeway to a “wilder” sensibility and to intuition, considering what is here and what is not, trying to believe in aspects of “other-than-human persons” as being part of our identity, expanding our point of view and defining time through a space that can be considered through the past, the present and the future. Because, shamanism operates on the principle that the past determines one’s future. When the shaman sees you, it is through your past, as well as your present. She/He is also able to give you about a glimpse into your future, and may be in contact with “what you don’t see” in order to influence that very future. Space and time are not conceived as a linear flow, but a fluctuation going back and forth.

Christine Laquet, I See the Sea and the Sea Sees Me, 2011, Artist Book. Image courtesy of the artist.

Laquet began the book aspect of this project while in residency on Daebu Island in the Yellow Sea. She was thinking a lot about the sea that surrounded the island but also about the act of seeing and looking as a strong act of choice that relates to a specific surrounding, the ways to see and the idea of who is seeing who (AND she was reading John Berger’s Ways of Seeing). She opens the book by stating “I consider that by being an artist is to see through something and to see something through and give a reflection”. Towards the end of the book Laquet takes a more political standpoint and delves into what drives us to look, and the idea that “desire is part of the economic system and the capitalist infrastructure, one which tries to control people’s hopes or desires. Capitalism remains a formidable desiring machine.” In between this philosophical beginning of the book and the political end, Laquet explores “seeing” and feeling energy and objects through interactions with the shaman community because she felt it was one with liberated desire.

Through a para-sensorial sensibility, an artistic creation and rituals, it creates a kind of “fourth dimension”. What I mean by a “liberated desire” is that it escapes the impasse of private fantasy: it is not a question of adapting, socializing and disciplining it, but of plugging it in, in such a way that its process is not interrupted in the social body and that its expression is collective. What counts is not the authoritarian unification, but rather a sort of infinite spreading. Shamanism points to the attribution of life, autonomy, power, and even dominance over otherwise inanimate objects, “other-than-human persons,” where the majority of social relationships are reduced to the magical matrix of things.

Laquet’s second exploration of this project consisted of an exhibition made in collaboration with artist Laurent Pernel while she was in Korea. They titled the exhibition the same title as the book and worked collaboratively, both of them next to the sea, but hundreds of miles away from each other. The exchange then became based on this idea of seeing, being in a close context though inhabiting different places, only the sea remaining. In this case, the sea became their portal to see each other. The images and exchanges were exhibited so the public could reconstruct one situation to one another.

In 1992, artist Tom Friedman created a piece titled Untitled (A Curse). The piece appears to be invisible. If you come across it in a gallery or museum, it is only an empty pedestal in a corner. In much of Friedman’s work there is an initial experience of what you see in front of you and then a secondary experience that occurs after you read his titles or process. In his description of this piece he writes that he employed a professional witch and she cursed the eleven inch sphere that rests eleven inches over the pedestal. He is quoted in saying he was interested in “how one’s knowledge of the history behind something affects one’s thinking about that thing”. This work tests the roles that belief and imagination play in our experiences and tests what we see versus what we believe we see.

In 2005 artist Jeppe Hein constructed a piece titled Invisible Labyrinth. Labyrinths are an incredibly old and universal theme that many artists and writers have explored as a setting and a metaphor. The elaborate unicursal structures are designed and built with a non-branching path that leads to the center and are not designed to be difficult to navigate. Often the word labyrinth is exchanged with the word maze but they are the opposite. A maze refers to a multicursal branching puzzle with many paths and directions. A labyrinth is considered to be one of the most universal symbols of life, the road we all must travel that is often mysterious, confusing, sometimes, scary, sometime, calming and beautiful. Much like the sea.

To make his labyrinth invisible Jeppe Hein used infrared technology. He then provided his audience with a pair of digital headphones that vibrate whenever one bumps into an invisible wall. The piece consisted of seven labyrinths in total and viewers were equally fascinated both to try to navigate through it as they were watching others attempt to do so.

In making the labyrinth invisible, Hein elevated the already powerful metaphor; one especially poignant in the context of our times. There are an incredible amount of invisible systems surrounding us daily now – from recent and continued revelations on living in a surveillance state to the amount of data that is transferred without ever becoming a physical form. I’ve always thought of artists as people who operate slightly invisibly too — a bit like Robin Hoods, slipping through systems, walking tightropes between society and the cosmos so they have a clear view of both but are not inside either. But are we in an era where we cannot be outside anymore? Even the further out or the further in we go, there are technological systems which are or can be put in place no matter where we go. I think within the myriad of questions many of these artists are asking in their work is also one question that feels like the large wave one can see when standing on the shore line building in its momentum as it moves closer: is it possible and what does it mean to live freely now?

Artist Diana Heise performed a piece titled Take Only What You Can Give in 2011. It was a sculpture as well as a participatory performance. Three performers lay down on reclaimed arson wood. They were then covered by hundreds of pounds of local clover seeds. The audience is invited to approach the performers with a small bag and take with them what they can be responsible for cultivating. In doing so they also released the performers from the weight of the seeds.

Diana Heise, Take Only What You Can Give, 2011, Sculpture/participatory performance, arson wood, red clover seeds, soil, soil-text haiku, 10 minute soundscape. Image courtesy of the artist.

Clover is a natural nitrogen fixing plant that restores soil. There are other plants that contribute to nitrogen fixation too such as soybeans, lupines, peanuts, and alfalfa. These plants are nitrogen fixing plants because they contain symbiotic bacteria called rhizobia in their root systems. These bacteria produce nitrogen compounds that in turn aid the plant growth but then when they die, the fixed nitrogen is released into the soil, fertilizing it. This makes the nitrogen accessible to other plants. This method is used in traditional and organic farming practices by rotating nitrogen fixing plants through various crops and both clover and buckwheat have been called “green manure”. By having the audience take a portion of these clover seeds under the agreement that they take only what they will be responsible for cultivating, Heise is affecting a large audience that then largely affects their environment around them.

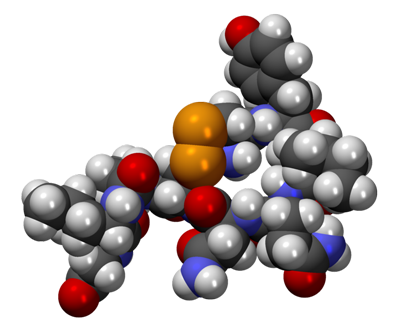

Oxytocin is the brain chemical that plays a crucial role in demonstrating the physiological effects of a specific molecule on us as social creatures with a physical need to give and receive love, to touch, feel empathy and compassion. Much research demonstrates it is an essential part of our daily needs for better performance in everything we do. Often referred to as the trust chemical, or love molecule, a focus is often on how critical it is for pair bounding in humans. But not only that – on a basic level a simple bodily contact with anyone throughout the day will cause the release of oxytocin in the brain. This is also experienced by the person that one is in contact with and the effect lingers afterward. One study even shows that simply gazing at someone or thinking about him or her will have this affect as well.

CPK model of the Oxytocin molecule C43H66N12O12S2. Image used with Creative Commons 1.0 Universal Public Domain.

To get a dose of oxytocin you can simply shake someone’s hand or hug him or her. It is linked to creating feelings of optimism, reduce stress, improve self esteem, trust, heal wounds (through its anti-inflammatory properties), increase generosity and empathy, and relieve pain. This is why it is now often referred to as the perfect drug. This is one molecule that we know affects our performance simply by interaction and touch. Heise’s piece also activates these processes happening to all involved that are touching and giving even at the molecular level.

“In art, and in painting as in music, it is not a matter of reproducing or inventing forms, but of capturing forces. For this reason no art is figurative. Paul Klee’s famous formula – ‘Not to render the visible, but to render visible’ – means nothing else. The task of painting is defined as the attempt to render visible forces that are not themselves visible.”- G. Deleuze

John Ensor Parker is an artist with a background in mechanical engineering and physics. But he also has a long history of making paintings as his medium to capture forces. In his piece You, Me and Everything In Between he addresses what is affecting us at the invisible level through quantum mechanics, and more specifically, quantum entanglement. In quantum mechanics particles can become entangled and interact over vast distances. Albert Einstein famously called this “spooky action at a distance.” It basically means that any two particles that have interacted before are bound to each other regardless of distance; one always affects the other. The piece is enamel and graphite text on aluminum, and the writing is equations of fixed length quantum entanglement. Similar to Holzer’s early practice of copying diagrams, Parker writes out the equations involved in quantum mechanics by hand. When he was working on the piece he was thinking about how quantum mechanics effects two people in love, so connected to each other physically that even when they are apart from each other, they are physically affecting the other person from wherever they are on a molecular level. He ends the piece with this idea in mind, deviating from the equations into off the cuff writing “hey you see me – pictures crazy. All the world I’ve seen before me passing by. Letting the day go – truly evolving. Its faith, its faith.”

John Ensor Parker, You, Me and Everything in Between, 2012, graphite and enamel on aluminum. Image courtesy of the artist.

All of these projects investigate in different ways in which what and who we cannot see are always affecting us. Whether this is through science or shamanism, intuition or emotion, these invisible worlds and connections also reveal a tremendous amount of information about who and what we effect – whether we are aware of it or not. Investigating these molecular languages through art helps us see the sea.

The Russian novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once said “To have a great writer is to have a new government”. He was pointing to the notion that there is something inherent in the act of creating or making – whether its visual art, writing, music, theatre, scientific invention, whatever it is – that is a way of offering a new language, new way of thinking, a new system, a new way of seeing – an alternative to ones we may otherwise presented with. Another writer, Mark Twain, wrote one of the most monumental books concerning slavery and racism in America still today – Huckleberry Finn. For him it was not a political act – it was a story. But the art of storytelling carries the potential of planting a seed deeply in an individual mind forever. Whether it is a story about love or one encouraging evolution, growth, action or change; it depends on the story and the teller. These artists see in seas of information, reveal much to us and show us through example that we must invent our own languages — that there are so many ways to see and hear each other beyond detection, and there are so many ways to listen.

He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without the least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

A map they could all understand.

The Bellman’s Speech, The Hunting of the Snark, By Lewis Carroll

References

Adler, Margaret, “Public Art at Williams”, Williams College Museum of Art, 2011, http://wcma.williams.edu

Baccile, Nikki, Balzerani, Margherita Nanoscience and art : beyond the invisible and the intangible, Plastik: Art and Science, January 2013, http://art-science.univ-paris1.fr/document.php?id=657

Cumming, Laura, “Invisible: Art about the Unseen 1957-2012 – review”, Hayward Gallery, London, The Guardian, June 2012, http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/jun/17/invisible-art-about-unseen-hayward-review

Dvorsky, George, “10 Reasons Why Oxytocin Is The Most Amazing Molecule In The World”, io9, July 2012, http://io9.com/5925206/10-reasons-why-oxytocin-is-the-most-amazing-molecule-in-the-world

Franklin, Amanda M., “Mantis shrimp have the world’s best eyes—but why?”, The Conversation, Phys Org, September 2013, http://phys.org

Fridman, Tom, “TOM FRIEDMAN EXHIBITED AT THE SAATCHI GALLERY”, Saatchi Online, 1992, http://www.saatchigallery.com/aipe/tom_friedman.htm

Gannon, Megan, “Scientists Make the Smallest Mona Lisa”, Live Science, August 2013, http://www.livescience.com

Kac, Eduardo, Aromapoetry, EKac.org, 2013, http://www.ekac.org/aromapoetry.html

Nitrogen fixing crops, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Nitrogen-fixing_crops

Sarah Walko is an artist and writer. She was executive director of Triangle Arts Association, a non profit arts organization in Brooklyn, NY for seven years and currently is Director of the Marble House Project. Her fiction and non fiction essays have been published by While Whale Review Literary Journal and Hyperallergic Art Blog where she is a regular contributing writer. Her visual artwork has been published by The Dirty Goat, Apple Valley Review, 2 River, A Capella Zoo, Awosting Alchemy, 5×5 Literary Magazine, Bathhouse, amongst others. Recent exhibitions include Preternatural at the Museum of Nature in Canada, Codex Dynamic in New York, A Necessary Shift in New York and DUMBO Glow in New York. She has participated in many artists residency programs including IPark and the Elizabeth Foundation. This past year she was invited visiting artist at Savannah College of Art and Design and Roger Williams College where she had a solo exhibition You and I Do Not Come Lightly to the Blank Page.