Anne Bujold

Anne Bujold (from the highway on her way to Taos, NM) asks Travis Townsend a few questions about his work. After some conversational pleasantries, she jumps right in.

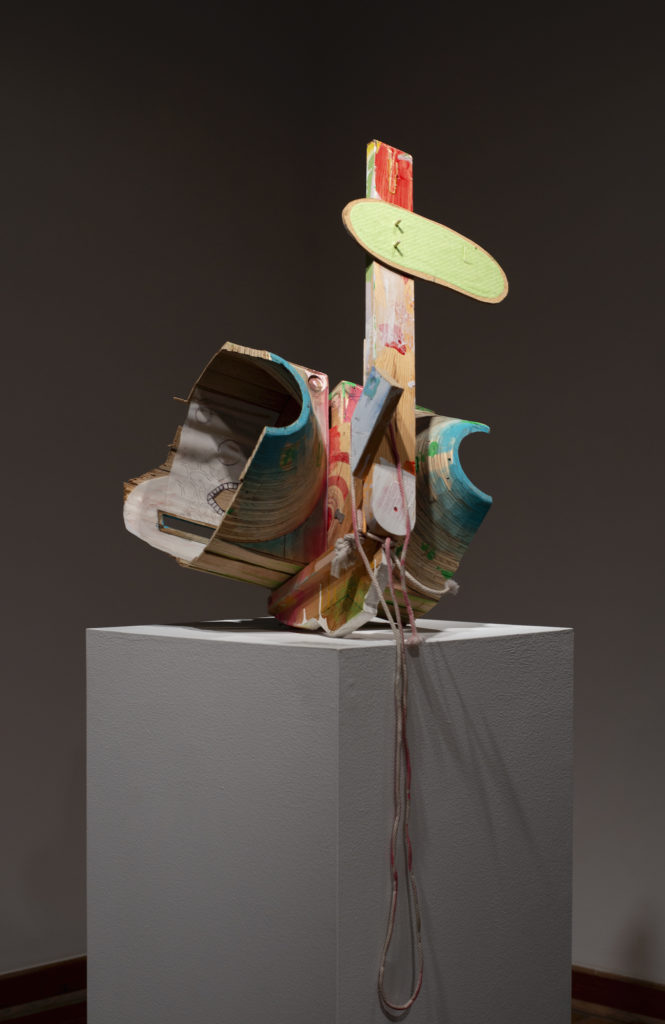

Installation view of Vessels of Destiny!

Anne Bujold: Tell me how you make decisions. With my students, I’ve often discussed your slowly evolving building and re-building process, the erasures, and the unrefined, but pleasing surfaces. But when do you actually know when to add, take away, or stop?

Detail of (saluting) Trophy Boat (with train), wood and mixed media (with some parts from my first childhood toy train set and parts from my son’s toys), 2007-2022.

Travis Towsend: Well, that’s a really good question, and one that is often the most difficult to determine. Sometimes I add something new (an object that has been lingering in the studio, perhaps) or create the overall shape fairly fast. These moments are exciting because it feels like progress. After much looking, though, many of these quick additions are removed, scaled-back or altered. These changes and erasures allow remnants of the creative act to linger. Often the evidence of the building process is more interesting to me than a finished object. And found materials (clamps, metal handles, string, old toys) somehow need to be “seasoned” by the studio process before they feel at home within the sculpture.

But I still wonder if some of my decisions are good ones. When looking back on a recent solo show, I feel slightly awkward about a few choices (a toy train as part of one sculpture, an

obvious “borrowing” of another artist’s Abe Lincoln).

(Left Detail, Right Full Image) (saluting) Trophy Boat (with train), wood and mixed media (with some parts from my first childhood toy train set and parts from my son’s toys), 2007-2022.

Elizabeth Murray- one of my favorites- states in an Art21 video that she knows she’s onto something good when the thing she’s working on makes her laugh, and I get that. So I’m trying

to develop the form in a way that teeters somewhere between clarity and disintegration. I want enough interesting shapes and techniques so it looks intentional, but I need the sketchy

in-progress quality to give it some energy and unexpectedness. Broken boats, old tools, and architectural sketches still seem like the departure points (in terms of where the initial drawings

begin and in what they might resemble when completed).

AB: And what about the layered mark-making?

TT: Oh yes, the surfaces! The drawings and written words are actual doodles of things to make or random to-do lists while thinking in the studio. Sometimes I try a very intentional image, but then that always seems too heavy-handed. Many marks are from my own kids drawing or painting and writing on pieces of plywood in the garage. I also have bins of scrap plywood and 2×4’s left over from my high school students. These things give me an existing palette of wood pieces. Usually, the object isn’t that interesting until something accidental happens to the surface. Just like with the 3D elements, these bits of drawing and painting are better as a collection of small moments rather than being the focal point. My hope is that the accumulation of marks, imagery, and paint drips communicate the evolution of the building process (I’m thinking very Ab-Ex here) and contribute to the object’s overall sense of history.

(Left) Two Rooms/Tool Thing (Virginia and our confounding fathers), wood and mixed media, 2021-2022. (Middle) Detail of Thing by the Door (with bird sign), wood and mixed media, 2020-2022, with some older parts. (Right) Vehicle of Strange Conception (EVIETA), wood and mixed media, with some older parts, 2007-2022.

AB: In previous conversations, you’ve mentioned your anxieties. I’m wondering how you wrestle with the futility of making in the face of this pessimism?

TT: Whoa, heavy duty. I’ll try to answer this and not sound too pessimistic. I think- if we’re being honest- all artists wonder about whether their life’s compulsion is an act of bravery or an act of complete selfishness. As a young art major at Kutztown, I considered switching from art to science, with the idea of doing something useful for humanity.

I’m now a middle aged dad. And I often find myself tinkering in the studio after the kids have gone to bed. The studio is the garage, which has been the domain (escape?) of middle class

fathers for generations. What am I building in there? Am I building good things or am I just puttering around? What is the environmental impact of the things men build? Does art do any

good? Yeah, I certainly have some doubts! And I think you can see these doubts in the work I’m creating. These Arks won’t save us and these devices are flightless. Is this a sad realization or

is it humorously illuminating? Can it be both?

(Left) Thing by the Door (with bird sign), wood and mixed media, 2020-2022, with some older parts.

(Right) Detail of The New Ship of Progress! (leaning in the corner of the room), wood and mixed media, 2020-2022, with some older parts.

That said, I find my work joyful. It is also a lot of fun to make. Hopefully, viewers see this. But recently, a subtle critique of “progress” and “manifest destiny” has come into the works (either by referencing it in the titles or in the use of secondary bits of imagery and writing on the surfaces). Will the actions in my studio make life better for my three children? Probably not.

But I’m still fascinated by the creative process. And it feels good to make something with your hands. Making art seems to be a way to offer the world something genuine. Overall, I wish to

build sculptures that open up imaginative pathways and allow for a few questioning conversations.

AB: With your perpetual cannibalizing and regeneration, does your work sort of answer its own question?

TT: That’s an interesting question, one that makes it sound like I’m onto something worthwhile!

Yes, I am constantly altering the sculptures, sometimes over the course of decades. I know, kind of stupid isn’t it? But I feel like there’s beauty in that. Nothing is ever trash and nothing is ever truly finished. Sort of like gardening, which is never the same twice and is never completed.

Arky (revisited), Big Pink Mothership, and Tool for Sorting the Two Americas/To See the Sea/Form Study/Gooey Goodbye, wood and mixed media, 2022.

Travis Townsend builds and rebuilds wood and mixed media sculptures in his Lexington, KY studio. His process-oriented works evolve from sketches and travel through many transformations before being cut apart, reassembled, and reworked (sometimes many years later). Parts are often transplanted or recycled.

Travis studied at Kutztown University (BS) and Virginia Commonwealth University (MFA) and has presented solo exhibitions at The Parachute Factory, Washington State University, Manifest Gallery, Weston Gallery, and the New Arts Program, among others. His awards include a residency at Penland School of Craft, an Emerging Artist Grant from the American Craft Council, a fellowship from the Kentucky Arts Council, and three sculpture grants from the Virginia A. Groot Foundation. He currently runs the visual art program at East Jessamine High School.

Anne Bujold is currently the Visiting Assistant Professor of Sculpture at the University of Louisiana, Lafaytte. She received her MFA from the Craft and Material Studies Department at Virginia Commonwealth University (2018) and BFA from Oregon College of Art and Craft (2008). She was the Artist-In-Residence for the Metals Area at the Appalachian Center for Craft in Smithville, TN (2018-2020).