Coline Souihol

This open conversation was conducted on 24 May 2023, in the office of Artist-Academic Selina Tusitala Marsh in the English Department at the University of Auckland.

Coline Souilhol: This issue of Drain explores the various representations and perceptions of the head. What does the head remind you of when you think about it in terms of representation and in relation to your artistic practices?

Selina Tusitala Marsh: People often comment on the silver streak in my hair. My grandmother on my father’s side – my English French grandmother – went completely silver when she turned 21 years old. I’ve got it, and my sister is starting to get it. Lots of people come up to me and say “Oh, I love your hair, I love your streak, you remind me of Elvira of The Munsters” (laughs). I love that because it’s the old and the new mixed together, right? It’s got this grandness to it.

When I first noticed the grey, I started dying it. But when I started kickboxing at age 35, I also began rediscovering different parts of myself, part of that was the strength I found in both my femininity and my age, the strength I discovered in being a woman who could move her whole body through a martial art. I hadn’t even punched anything let alone anyone before, never mind execute kicks to the head! I’d be grappling in the ring with men, rolling around and elbowing, just completely emancipating myself from the idea of what respectable ‘darling’ women do. So, the streak took on metaphoric power – the power to be singular, different, powerful in my own way. So it stayed.

https://www.selinatusitalamarsh.com/

CS: How do you connect the ‘darling’ woman with the evolution of your creative process and practices over the years?

STM: The opening lines of Alice Walker’s poem “Be Nobody’s Darling”[1] read: “Be nobody’s darling/ Be an outcast./ Take the contradictions/ Of your life/ And wrap around/ You like a shawl,/ To parry stones/ To keep you warm.” It reminds me that I am strong. I am strident. I don’t need your approval. I don’t want your approval. I’m exactly in this space. I can be nobody’s darling in a whole host of different ways.

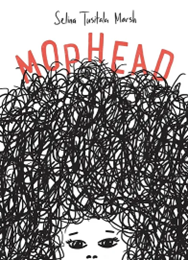

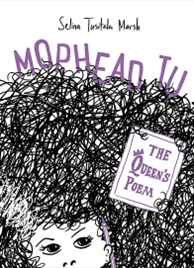

When I embarked on Mophead, my graphic memoir series, I was totally embracing my “non-darlingness”. One of my colleagues called it “academic suicide”. To not be writing peer reviewed research articles and to start writing and drawing my own all-ages books was seen as ‘crazy’. She advised me that I needed to focus on getting promoted by researching and publishing in A grade academic journals. That exchange brought to mind a universal spiritual truth: all behaviour is based on one of two emotions: we’re either acting out of fear or out of love. I saw her shrill insistence of maintaining the status quo of how to be an ‘academic’ as a behaviour based on fear, on proving my ‘worth’. I needed to do certain things how they’ve always been done if I wanted to get promoted. But getting promoted has never been the main reason why I am here. I’m here to be a ‘tusitala’, a storyteller, to tell my own tales, and the tales of others’ whose stories are often marginalised in this environment. I get to create my own stories and flourish creatively in this institution. It’s not without struggle but I get to do this and it’s a relative privilege to occupy this role at university.

CS: How do you bridge the Artist-Academic together?

STM: Creating Mophead was an epiphanic moment for me. It gave me insight into my non-darling moment of rebellion: this is how I’m going to do me, as an academic, and as an artist. This is how I am going to embrace what I mean when I call myself a Pasifika poet-scholar or what’s more commonly referred to in the scholarly research in this area, as an Artist-Academic.[2] I am now what I’ve termed as being ‘led by line’, not by other people’s line but by my own line. If I am to survive and thrive in this place, I cannot deny my own natural way of being. If I deny myself in this way, I am not going to last very long. There are many disenchanted colleagues I know who have left academia resentful and bitter. They feel used up and spat out by the institutional machinery. Mophead is about how our difference makes the difference; the thing that makes us uniquely ourselves is our superpower. We just need to grow the eyes to see it, recognize it and claim it. It’s about identity, knowing who I am, and giving myself permission to be many selves so I don’t just have to be a peer-reviewed published scholar. I can do that, and more. I can draw my own pictures and write my own stories for children of all ages.

Mophead: How your Difference Makes a Difference (2019) and Mophead Tu: the Queen’s Poem (2020) https://www.selinatusitalamarsh.com/publications

CS: When did you choose to introduce the drawn line to your poetic line? How did you get from the written line to the drawn line and merge the two?

STM: To begin with, we all are led by line. Most of us were kids who drew and wrote our own pictures and stories and thrust them into the world. That ease, that belief that we are all artists, slowly got educated out of us (see Sir Ken Robinson’s TED Talk ‘How Education Kills Creativity). My re-entrance into margining the drawn and written lines was an on purpose accident! (laughs). There’s a poem that I wrote called “Led by Line”[3] dedicated to the Oceanian women poets. Before I published it, I transferred the text of the poem on my Ipad and I drew these swirls and decorative patterns in between the lines because I wanted it to ‘be’ the thing it was calling forth, and there’s an active use of space in that poem. That was my first kind of mixing of the visual line with the written line. There is, of course, a huge leap between that experimentation and coming up with the first draft of Mophead. I pushed myself into making something big because I wanted the story to be read by as many people as possible. My tolerance for confining my research to peer reviewed academic articles has come to an end. I’ve increasingly become less satisfied with the default way of disseminating university research —I want my work to reach as broad an audience as possible. I want it to sow seeds of raucous possibility early. I also wanted to sink my teeth into something quite different. I’m having too much fun doing Mophead stuff at the moment to stop!

One of my other projects is a digital illustrated poetic dictionary called Wunpuko Words. Wunpuko is a little village on the top of Espírito Santo, my partner’s late father’s village. I was trying to pick up the local language, Vanlav, and began writing down words and asking kids and aunties for definitions. They had a hoot of a time debating the word for a specific object which changed depending on its context. My enquiries about a written source of words revealed that my partner’s father had begun recording the language somewhere but never completed the project. That’s when I realised that I had an opportunity to get Vanlav down on paper in order to create a foundation that the community could build upon and debate over. It’s all about necessity and creativity, right? How do we get the stories and words out there so other people can learn and be inspired? I am not a linguist, but I am a poet. And an artist-academic. And a storyteller. So I return to Wunpuko soon and have another chance to go back with the words I collected last year with little illustrations and give it back to the community. I’ll savour and mull and debate over what I captured and then return it to the community and see what they want to record. Wunpuko Words is a really great led by line example because I am following the bloodline (through my partner) which gives me familial access to the village, and then employing the written and the drawn line to lay down ‘a’ line that the community can then expand upon. I am not an anthropologist so, for me, the most important thing is getting the stories out there to celebrate our own humanity, our environment and the spaces between us. This is especially the case when the kids are in their village school learning French and English but not Vanlav.

CS: Speaking of spaces, you use a digital space to create Mophead.

STM: The ipad has enabled me to sidestep my internal sensor (“who do you think you are? You’re not an artist.”). The ipad is easy. I can just wipe the screen and start again, or change layers. I don’t have to painstakingly paint or draw something and then discover I’ve made a mistake and have to start all over again. It is so quick and easy and fast and I really love it. It seems more casual, as if I am able to fool myself into being an artist. I’m getting better at accepting the label of artist because I have been following other artists whose aesthetics are more line drawings and I think if they can do that, I can do that.

CS: How do you tap into your creativity?

STM: I visit schools… a lot. And that’s about making my work fun for kids to learn about our own Pacific stories, who I am and what I do – especially when I talk about the poet laureateship. When I came up with the Mophead character, I drew her/my hair first, and then her/my eyes. These body parts symbolise the ways I see the world and the way in which the world sees me and the difference that my hair makes. The very source of my perceived disempowerment (I was teased at school because of my hair) actually depends on how I see my hair. Now it’s my source of empowerment. I love the simplicity of that truth, which is why the Mophead covers are close-up headshots because I want a strong visual connection with the reader, as if to say, ‘I see you, do you see me?’ It is extremely satisfying to be able to scribble and to draw in a way that embodies the quirky and accessible aspects of my personality. Mophead is not fine lined and perfectly formed. She’s bold and quirky. She’s all angles and explosively expressive. What you see is what you get. When a draft manuscript goes to my publisher, they ask me to make Mophead look consistent throughout the whole book because sometimes the head or the body is bigger or smaller. I’m not a trained artist. I don’t see Mophead’s head as a third of the size of the body and the body as two third of …you know? I just draw her according to how I feel at the time. That’s all good for draft work, but not the finished, polished product. It’s why each book takes an average of two years from draft to publication.

https://mophead.co.nz/about-selina/

CS: If we think about your Led by Line methodology, the head and visual representation, what does it all come down to for you?

STM: It all comes down to this: Mophead’s hair. It is the interconnection of all these lines with no particular hierarchy. Her hair isn’t categorised or contained. It’s full of movement, vitality and fun and it is a lot of work! (laughs). If I were to draw something, it would be that kind of scribbly, wandering line on the page, where, if you look hard enough, you see both the positive line and the negative space. You need both in order for it to convey the message that all these lines are permissible and have a life of their own. They intertwine according to their own dictates.

At one point I was trying to decide whether to draw Mophead’s hair as a completely black block, but I really wanted the aesthetic of the scribble. We often find scribbles or doodles in the marginalia of texts and my work is about bringing the margin to the centre. It is how I engage with a text. When I read, I like to write in the margin, underline, circle, and write down thoughts. For me, the learning and creative process experience is all about learning as you go and trying different things. If we are too scared to start because we are too scared to fail, we are living out of fear rather than out of love for the creative process, for storytelling and for making.

Like Mophead’s hair, my hair attracts things, things get stuck in it, it is almost like a dream catcher: whatever comes my way gets caught, a little piece of it stays behind to feed my creative process. I endeavour to stay open to inspiration and being inspired by the things around me.

[1] Alice Walker, “Be Nobody’s Darling” in Revolutionary Petunias and Other Poems. Amistad, 1973.

[2] Marsh’s profile on the Artist*Academic website: https://artist-academic.com/who/selina-tusitala-marsh/

[3] Marsh, “Led by Line”, Tightrope. Auckland University Press, 2017.

Selina Tusitala Marsh is a New Zealand born Pacific Islander of Samoan, Tuvaluan, Scottish and French descent. She is ONZM, FRSNZ, 2017 New Zealand Poet Laureate and Commonwealth Poet. She is a Professor of English and teaches Pacific and Māori literature and creative writing. In this discussion, she reflects on the metaphor of the hair and how she extends it to her multidimensional personality, her creative process, how she navigates her various differences in and beyond the academy, and her life as an Artist-Academic.

Coline Souilhol is a PhD. student in the English Department at the University of Auckland. She is investigating Francophone translations of Pacific women writers.