Tracy Adams

Hollywood and the modern beauty-industrial complex have trained several generations of western men and women to regard high cheekbones as a marker of female beauty.[1] Few living today within societies that prize ‘white’ features would dispute the point, as the most cursory internet search suggests.[2]

And yet, western beauty cultures have not always valued high cheekbones. Evolutionary psychology targets them, along with ‘large eyes,’ ‘thick lips, thin eyebrows and a small nose and chin,’ as features that ‘significantly influence the perception of facial attractiveness’ in females.[3] However, if an evolutionary preference for high cheekbones existed, they would be prized across time and space. This is manifestly not the case, some Asian cultures showing a preference for an oval face shape without prominent cheekbones[4] and western cultures extolling high cheekbones only since the middle of the 1920s when Greta Garbo arrived in Hollywood. A few extremely general traits like clear (as opposed to pock-marked) skin, symmetrical features, and relatively white teeth in adults seem to be universally admired.[5] And yet, one can easily imagine an unattractive female face with clear skin, symmetrical eyes, and healthy teeth. Although such general traits may be prerequisites, they are not determinative of beauty, which instead depends on a constellation of subjective factors. Do observers prefer thin or well-defined eyebrows; sleek or curly, blond or black hair; tan or pale complexions; Roman or short noses; prominent or delicate chins? And, most relevant here, do they prefer a face with visible bones or a smooth round or oval one?

In what follows, I focus on this final question to explore some of the cultural meanings that the current western preference for prominent cheekbones encodes. I suggest that the preference, visible in writings and advertising related to female facial beauty, particularly in Hollywood fan magazines of the late 1920s and 1930s, reflected and reinforced some of golden-era Hollywood’s ambivalence toward cultural diversity.[6] Focusing on the frequent references to the feature in these publications, I contextualize its fetishization as part of two intersecting trends: the democratization of the make-up industry and the ‘orientalizing’ esthetic already present in many films of the first years of Hollywood’s golden era. High cheekbones, I propose, symbolically registered and resolved flagrant contradictions embedded in these two trends. In the first case, the beauty-industrial complex needed beauty to be both an inexpensive commodity (cheekbones could be faked in real life through the application of make-up) and an exclusive gift from the gods (female stars had to be different from their ordinary sisters). Cheekbones, in this context, were a form of symbolic capital that cut across classes but served a gatekeeping function as well: if you had them, you might succeed in Hollywood, however lowly your background; if you didn’t, you could forget a career in the movies, however prestigious your background. In the second case, ‘exotic’ peoples and locales were popular in Hollywood films, but film audiences, like many Americans, were racist.[7] In exalting cheekbones, Hollywood transcoded a feature traditionally identified as non-white to allow racist audiences to indulge in the pleasure of the ‘exotic’ and, at the same time, soothed their anxiety with the production of the utterly incoherent ‘race’ clauses of the infamous Hollywood code, which for all practical purposes required ethnic characters to be played by made-up white actors.

The rise of high cheekbones as a marker of beauty

To begin, it will be useful briefly to follow the rise of this popular marker of beauty. In Romantic Love and Personal Beauty: Their Development, Causal Relations, Historic and National Peculiarities of 1887, Henry T. Finck devotes an entire chapter to cheekbones, announcing that this matter of taste has been decided in ‘our’ (meaning white) favor by the general laws of Beauty: ‘high, prominent cheekbones are ugly.’[8]

[I]n the first place, because they interfere with the regularly gradated oval of the face. Secondly, because like projecting bones and angles in any other part of the body, they interrupt the regular curve of Beauty. Thirdly, because they are coarse and inelegant, offending the sense of delicacy and grace, like big, clumsy ankles and wrists. Fourthly, because they suggest the decrepitude of old age and disease. In the healthy cheek of youth and beauty there is a large amount of adipose tissue, both under the skin and between the subjacent muscles. When age or disease makes fatal inroads on the body, this fat disappears and leaves the impression of starvation.[9]

True, the ‘lower races’ prize prominent cheekbones, Finck admits, but this is because the ‘standard of primitive taste is not harmonious proportion and capacity for expression.’ According to him, the ‘lower races’ seek exaggeration, preferring a ‘monster of ugliness.’[10]

Finck was not an outlier in his overt racism or taste regarding female facial beauty. A glance through pictures of white women from the end of the nineteenth century reveals the ideal face to have been gently curved, tapering to a rounded, often dimpled chin, with generous cheeks and no visible hollows under the cheekbones. That basic shape remained in vogue throughout the early days of the silent film industry, as pictures of Lilian Gish and Mary Pickford attest.

|

|

| Lillian Gish | Mary Pickford |

Moreover, portraits of Hollywood’s first vamps suggest that dark hair, eyes, and lips were associated with the industry’s version of exoticism, but high cheekbones, today the very hallmark of exoticism, receive no emphasis.

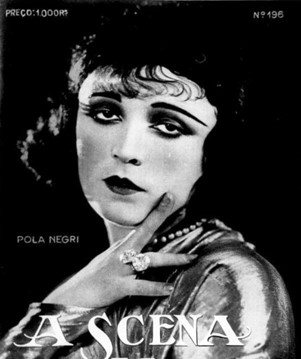

|

|

| Theda Bara, early vamp | Pola Negri, early vamp |

High cheekbones appear as a point of controversy in a 1923 issue of Motion Picture Magazine, in the context of a debate over the most beautiful faces in Hollywood. One of the judges, a well-known illustrator of fan magazine covers, Neysa McMein, includes silent film actor Pauline Stark’s face among the most beautiful, specifically because of her prominent cheekbones. In this choice, McMein bucks the popular opinion that ‘Miss Starke’s cheekbones were her handicap….’[11] Readers’ responses to the debate in subsequent issues include the more common opinion expressed by the self-described ‘very ardent reader’ Carl L. Kraus. Kraus dislikes any prominent features, fretting that Hollywood illustrator Clarence Underwood ‘has a tendency to make his girl faces pointy and bird-like.’ In addition, Underwood’s faces ‘generally have very straight noses and chins.’ Underwood is not the only offender, according to Kraus: ‘E. Dahl … makes the chins a trifle too large for the rest of the face. William T. Benda has a tendency to give his faces that slant oriental appearance.’ As for McMein, Kraus complains that the most noticeable trait about her faces is ‘high cheek bones.’ Kraus prefers an even balance with no the ‘pronounced’ features: beauty equates with a round face with large eyes, full cheeks, ‘and a mouth that goes well with both….’[12] An issue of Photoplay from 1925 reveals that high cheekbones were still considered a fault of proportion, at least by some. Beauty advice columnist Carolyn Van Wyck echoes the opinion, suggesting ways of minimizing facial defects without surgery. A certain Peggy, writing to Van Wyck, laments that she is ‘uneasy when out in public because of a long and rather pointed nose….’ Van Wyck puts a conspicuous nose and high cheekbones in the same basket, admitting that in extreme cases, a woman might opt for ‘facial surgery or kindred means’ to correct features that ‘are out of proportion.’ But often, ‘a change in hairdressing will soften the effect of a prominent nose or high cheekbones.’[13]

However, in that very year, a major shift begins, and what had been a defect quickly becomes the supreme marker of beauty: the ‘golden age of the cheekbone’[14] arrives with the appearance of the young Swedish actor Greta Gustafson in Hollywood in July 1925. Well before her move to the United States, Gustafson, beautiful of face but somewhat heavy of body, had embarked on a film career, her big break coming when director Mauritz Stiller cast her in The Story of Gösta Berling. At her first meeting with Stiller, she dazzled the director with her lovely features but dismayed him with her weight, reportedly prompting him to proclaim, ‘but miss, you are much too fat![15]

Young Garbo

Stiller demanded that she lose twenty pounds. She complied, as Life magazine recounts. But if twenty pounds was sufficient for the Swedish director, it was not for the rigorous Hollywood star system. As the renowned British novelist Zadie Smith writes, MGM’s Louis B. Mayer was not impressed with the young Swedish woman’s appearance. Meeting up in Germany with Stiller and Gustafson, who had by that time become Greta Garbo under Stiller’s guidance, Mayer invited the pair to come work in Hollywood. But he also warned Stiller that in the United States: ‘we don’t like fat women.’ Garbo is reputed to have gone on a spinach diet for three weeks, lost weight, and remained, as Smith puts it, ‘slender, shapeless, suggestive of a dangerous lack of physical vitality—throughout her movie career.’[16]

But that face – her cheekbones had appeared! Smith writes: ‘Garbo’s shots, lit with the “Rembrandt lighting” that would make her famous, are sculptural portraits, more Rodin than raunch. The Garbo image is yet unformed, but the beginnings of an iconic persona are here. She had a relationship with light like no other actress; wherever you directed it on her face, it created luminosity.’[17]

Garbo, Hollywood style

A.O. Scott, critic-at-large for The New York Times, attributes Garbo’s cheekbones with a magical aura. On the one hand, he opines, some stars possess a charisma that ‘amounts to a kind of distilled ordinariness.’ On the other hand, there is the ‘rarer breed whose beauty is almost too unearthly to be sexual….’ Greta Garbo epitomizes the latter type of star. The distinction between the two, he continues, which is ‘obvious to any moviegoer, arises from a number of ineffabilities having to do with talent and technique.’ But for the most part,

it’s a matter of cheekbones. Cinema, with its bright lights and character-establishing close-ups, infuses the ridges and declivities of the human face with expressive power. Good bone structure confers a kind of immortality, as well as offering some immunity to the depredations of time, especially for women. Men grow thick and jowly, but even in their old age, stars like Gloria Swanson, Katharine Hepburn and Jeanne Moreau have managed to defy gravity.

Scott concludes: ‘The black-and-white era was the golden age of the cheekbone. The glories of Greta Garbo in close-up, those evocative shadows and hollows, will never be matched in Technicolor or digital video.’[18]

Journalists of Garbo’s own time were equally awe stuck by the star’s bone structure, as evidenced by the many articles in fan magazines devoted to the glorious face. The mid-1920s were still early years for the Hollywood star system, but the first major fan magazine Photoplay had already been founded in 1911 and was going strong by Garbo’s time, joined by Motion Picture Magazine, Modern Screen, Screenland, Daily Variety and many others.[19] Photoplay magazine emphasizes her fabulous cheekbones among the features that guarantee her status as a model of beauty, reporting that: ‘people are comparing [Katharine Hepburn] to Greta Garbo, because she is like her photographically. Garbo, too, is tall and thin—Miss Hepburn weighs only 107 pounds. Garbo has the same broad brow and high cheekbones, the same delicate yet square face, the same full mouth and heavy-lidded eyes.’[20]

Another article dissects her ‘X’ quality, describing Garbo as ‘exaggeratedly long and lithe. Her hands and feet are large. Her face has a bony contour— almost gaunt at times. High cheek bones; large, expressive mouth; long, slender neck like a stalk to hold the exotic flower-head.’[21]

Glamorous Garbo

In a Photoplay weekly feature called ‘Brickbats and bouquets,’ letters to the editor to praise or criticize stars, one film fan throws a ‘brickbat’ at Garbo, serving as the exception that proves the rule. The fan resists the general consensus, complaining that the actor, with her ‘hollow cheeks’ and ‘drooping eyelids,’ looks ‘fit for a sanitarium.’ But in that same feature, in the very next letter, the author lauds prominent cheekbones. This time the reference is to Hepburn: ‘Three cheers for this delightful girl with the bony, lanky body, big mouth, high cheek bones, gorgeous eyes and exquisite brow.’[22]

Katharine Hepburn

Garbo’s face had begun a trend. Soon other female stars were extolled for their cheekbones. Anna Sten, who resembled Garbo, ‘was a radiant vision who did, in the delicate purity of her features, in the high cheekbones and shadowy hollows of her face, suggest the Swedish girl’ and was ‘an aesthetic treat to watch.’[23]

Anna Sten

Luise Rainer was ‘so tiny and pretty, and her black eyes are big and she has lovely cheekbones.’[24]

Luise Rainer

The trend continued throughout the 1930s into the 40s and 50s. Cameramen enjoy filming Deborah Kerr because ‘her wide forehead and high Scottish cheekbones are a cinch to photograph.’[25]

Deborah Kerr

An article on Alfred Hitchcock’s The Paradine Case of 1947 marvels at the instant stardom of the film’s beautiful heroine, Alida Valli, recently arrived from Italy, described as a ‘Tragic, beautiful woman standing in the witness box.’ The article gushes about an arresting Valli: ‘tears well up in the wide blue eyes, sloe-tilted at the corners’ and ‘huge tears full of the flavor of bitter hopelessness — roll over the soft curve of the high cheekbones….’[26]

Alida Valli

Further praise appears in a 1952 article announcing that Rock Hudson, ‘who’s had ample opportunity to observe, believes Gene Tierney has the most beautiful cheekbones in Hollywood.’[27]

Gene Tierney

Cheekbones, then, became established as a marker of beauty around the mid-1920s. But in contrast to many other trends that have come and gone – platinum blond hair, pencil-thin eyebrows or, conversely, thick Joan-Crawford-style eyebrows, tiny bow-shaped lips or wide smiles – they have never lost prestige. Even today, their status remains unquestioned – the internet is filled with advice on how to make one’s cheekbones more noticeable using make-up. A website called ‘Fashion Republic’ affirms that ‘high cheekbones have become the universal symbol of beauty.’ Moreover, ‘while multiple factors contribute to a model’s beauty, one thing remains consistent – high cheekbones.’[28] Another website features a facial cosmetic surgeon who lists the ten female actors whose cheekbones his clients most covet. Number one on the list is Keira Knightley. Her cheekbones ‘are the first thing you notice about Keira’s face and give her an ageless beauty which will endure right throughout her career.’[29] Furthermore, an article entitled ‘Cheekbones That Changed The World’[30] begins by surmising: ‘Perhaps the obsession with highly defined and dramatized cheekbones started with black and white film.’ But the obsession followed stars into technicolor, and today, ‘in full color, celebrities with fabulous bone structure and mile high cheekbones continue to be envied.’ The article invites the viewer to ‘click through this gallery to see which celebrities of past and present have raised the bar,’ and to ‘see the celebrities with cheekbones so high, and perfect, and face shapes so enviable, women across the world fumble with their blush brush in an effort to contour and copy.’

Cheekbones and the democratization of beauty

Whether high cheekbones owe their sudden and enduring popularity to the influence of Garbo alone or a combination of factors, they became popular during the same period that beauty products became widely available, and they must be examined within this context. The democratization of beauty that marked America in the 1920s and 30s – the onset of readily available mass-produced fashion and make-up – and its connection to Hollywood has been much studied in recent years. Sarah Berry, writing of the fashion industry, explains that in

the mid-1920s, American popular culture began to show signs of ‘fashion madness,’ stimulated by new methods of production and the opening of department and chain stores across the country. The previous century’s time lag between wealthy women’s adoption of Paris trends and their gradual uptake by seamstresses, home sewers, and secondhand shoppers was dramatically shortened by these new production and distribution methods. In addition, new media and fan cultures began to erode the authority of traditional society ‘fashion leaders’ in

favor of popular celebrities. When a 1929 women’s magazine advertisement gushed about a line of ‘Famous Folks’ Frocks,’ it was referring to styles worn by ‘popular star’ of Hollywood, not by the socialites traditionally featured in fashion magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.[31]

As for the make-up industry, it boomed from the 1920s, offering ‘hope in a jar,’ as Kathy Peiss expresses it in the title of her socio-historical study of the rise of the American beauty industry. Formerly stigmatized as immoral, cosmetics became a fixture in everyday life, allowing women of all classes to aspire to the versions of feminine beauty made popular by Hollywood. ‘The consumer culture that emerged in the 1920s, with its emphasis on advertising and media-based marketing,’ she writes,

is today so integral to American life that it appears an inevitable, almost natural development. Cosmetics, consumption, and femininity seem part of a seamless fabric. In this formative period, however, mass-market firms actively searched for ways to package their goods that would legitimize cosmetic products and practices still questionable in the eyes of many Americans.[32]

Whereas female identities had previously been a function of ‘parentage, class position, social etiquette, and sexual codes,’ by the 1920s they could be created and managed with cosmetics. The expression ‘make-up,’ Peiss explains, became common in the 1920s and ‘connoted a medium of self-expression in a consumer society where identity had become a purchasable style.’[33]

A perusal of Hollywood fan magazines reinforces Berry and Peiss’s arguments, revealing a conception of beauty as a goal available to any woman who was willing to work hard at it.[34] Advice columnists insisted that beauty was an artificial effect that any woman could learn to replicate: the result of adherence to prescribed regimes. One columnist, writing for Motion Picture Magazine, proclaims: ‘[A]lmost any girl or woman who will give enough study to her make-up, style and carriage, may, if she has or can acquire that charming something called personality, gain a reputation for beauty.’[35] ‘A budget for beauty? Why not?’ asks Screenland. In fact, as the article argues, all women should ‘set aside some time, every day, for beauty.’[36]

With the help of reasonably priced cosmetics, women could make themselves up to resemble the star whose look most closely resembled their own. But even the stars themselves were not all gorgeous by nature, the fan magazines insist.[37] In fact, not one of a list of forty stars and near stars can be called a perfect beauty, announces Motion Picture magazine: ‘The majority of our exquisite ones, I am afraid, are largely synthetic! Make-up and the right clothes will do wonders to conceal defects and enhance whatever natural beauty one may be fortunate enough to possess.’[38] To further heighten the impression that beauty was within the reach of the everyday woman, fan magazines interviewed stars in their homes, looking like normal people. Myrna Loy claims to have worked hard for her beauty, describing herself at sixteen as feeling ‘absolutely paid in full for all the time and effort I had spent trying to improve myself… Valentino had told me that I looked lovely!’[39]

Myrna Loy

As for cheekbones, they too were available to any woman who knew how to apply makeup effectively. How specifically did a woman create the illusion of cheekbones if she was lacking in that area? Photoplay offers instructions for creating a ‘new face’ that included them:

If you’ve been looking at yourself mournfully in the mirror and wishing to heaven there were something you could do to disguise the fact that your nose is too long, or your cheekbones too low, you can perk up and take heart because there is something you can do about it. Of course, it isn’t any too easy, and it takes a lot of time, but it’s worth all the trouble if you really want to look alluring.[40]

A guide to make-up for the camera explains that:

a high light of very light foundation color may be applied to the chin to help compensate for a receding tendency here, or to the cheeks to lend contour where it may be lacking. A shadow of dark foundation may shorten and beautify a too sharp or too long chin, or it may be applied to the hollows of the cheeks to accentuate high cheekbones and slenderize the face.[41]

But what was the advantage of creating a new face to look like a movie star? Beyond the self-confidence it inspires, beauty is presented in these magazines as a form of capital, available to women of all social classes and, most important, exchangeable for fame and/or fortune. Women were enticed with promises that they might become stars themselves. Early Hollywood beauties often came from disadvantaged backgrounds, a point that magazines emphasized to nourish hope among female fans that ordinary women, including themselves, could win a movie contract through a lucky break or a series of breaks. According to Screenland, such breaks are so common in Hollywood ‘that it almost goes without notice.’ And, if she failed to make it in Hollywood, she could always marry a rich man.[42]

The democratization of beauty turned women into consumers of a vast array of fashion, cosmetics, and other beauty products. But it also created uneasiness. According to the 1929 sociological study, Middletown, middle-Americans did not like having formerly clear-cut social boundaries effaced by young working-class women so beautifully dressed and made up that they were visually indistinguishable from their more affluent sisters. Voicing a complaint reminiscent of the attitudes that resulted in medieval sumptuary laws, one interviewee reported: ‘I used to be able to tell something about the background of a girl applying for a job as stenographer by her clothes, but today I often have to wait till she speaks, shows a gold tooth, or otherwise gives me a second clew [sic].’[43]

As for Hollywood, a social hierarchy was also at work: elite and ordinary beauties needed to be distinguished but for different reasons. Even as it promoted the consumption of fan publications by convincing women that they too could become stars, the industry needed to do extensive gatekeeping to manage the aura of beauty, to perpetuate what anthropologist Annette Weiner named the paradox of giving while keeping.[44] Beauty must circulate and be available to maintain consumer interest. But, to retain its value, it must also remain out of the reach of most women, the very highest, most prestigious form available to only a select few.

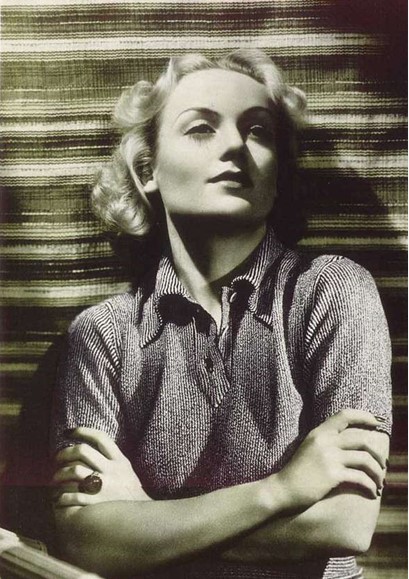

Fan magazines and films present beauty in this paradoxical way, with high cheekbones performing a crucial function as a means of distinction. Beauty was a practice and, therefore, available to ordinary people. But it was simultaneously a special grace visited upon a girl at birth, ‘the caprice of the gods, who deal it out haphazardly,’ as Screenland affirms.[45] In Hollywood magazine, Carole Lombard distinguishes beauty as an ‘applied art’ from the type that one is ‘accidentally born with.’[46] The former required only the skillful application of cosmetics that were easily within the budget of any woman. ‘In nine cases out of ten a woman can cut her cosmetic bill in half by buying exactly what’s suited to her complexion— and not to that of her friends,’ Lombard explains. Moreover, ‘Half used lipsticks, discarded rouges, wrong eye-shadows that clutter up a drawer are mute testimony to unguided buying.’[47] The other type of beauty, upon which Lombard with her legendary cheekbones does not discourse in detail, is available only to those blessed with good bones.

Carole Lombard

If fan magazines were invested in persuading readers that they too could look like movie stars, they also insisted that Hollywood beauty, as opposed to what passed for beauty in the rest of the world, did not lie in the superficial decoration of make-up. Instead, it lay below the surface in the bones. Rolf Armstrong, an artist noted for his ‘exquisite cover girls,’ pronounces that ‘beauty is a sheer, cruel, uncontrollable accident of birth. It exists primarily in a rigid combination of architecture and mathematics.’[48] In a New York Times interview by Idwal Jones, Paramount’s make-up artist Albert McQuarrie elaborates the point. Jones sets the tone, asserting that a female star turned loose in a crowd will attract attention because of the indefinable quality that made her a star in the first place. McQuarrie himself narrows in on that indefinable quality: it is a particular shape of face. A star’s face is perfectly symmetrical with a ‘hollow cheek, usually, with eyes wide apart and a paucity of eyebrow.’[49] Good bones cannot be created where they do not exist, and they are rare. McQuarrie submits, without explanation, that there are always twenty-four, never more, never fewer, top female stars at any one time.

But perhaps most interesting of all, the difference between beauty as applied art and gift from the gods was not perceptible to the naked eye. It could only be discerned with technology and expertise. A cameraman interviewed in Hollywood magazine who supposedly photographed the most beautiful faces on earth explained that star-level beauty was a fluke or gift of nature. Although many women are beautiful in real life, ‘camera beauty … is the beauty of symmetrical features, of facial contour.’ Indeed, the ‘average beautiful woman lacks this symmetry and balance of feature and she looks a fright on screen.’[50] Or as New Movie Magazine bluntly notes regarding screen tests, ‘Maybe you think you are beautiful—and doubtless you are, in an off-screen way—but wait until you have a film test.’[51] One ‘famous movie director’ defends the Hollywood elite against an angry public in New Movie Magazine, explaining that the industry was not really elitist. The problem was that most women weren’t beautiful enough to make it into the system. To a woman decrying the Hollywood ploy of sending out casting calls for an unknown female actor and then hiring a member of the Hollywood establishment (in this case, Margaret Sullavan), the director offers hard but realistic advice: forget it.[52]

Cheekbones were an essential marker of genuine beauty.

The great beauties of the screen – Garbo, Joan Crawford, Silvana Mangano – all had well-structured faces. The nose was sufficient and well-defined, the cheekbones high, the eyebrows nicely drawn, the jawline splendid. A good bone structure allows the light to ‘hold’ on a face and create an interplay of shadows. If a person ‘has no bones,’ if the face is flat, the light has nowhere to fall.[53]

The close-up became the ‘acid test of beauty,’ or so declared ‘45 Hollywood directors,’ as an ad for Lux soap in Screenland announced.[54] In other words, everything came down to good bones.

Even as the Hollywood beauty system appealed to ordinary women to turn themselves into beauties, the film industry withheld entrance for all but those whose bone structure revealed itself in pronounced glory under the lights.

Cheekbones and the “orientalizing” esthetic

The emphasis on cheekbones as a marker of beauty could be seen as democratic, whether as an illusion created by make-up or as a form of capital visited upon female faces with no regard for money or status. In either case, ethnicity theoretically should not have mattered: pronounced cheekbones cut across ethnic groups. A second trend, what has been called an ‘orientalizing aesthetic,’ should have further enhanced Hollywood’s chances of becoming an ethnically diverse industry. During the 1920s, the esthetic, emerging from the more general film esthetic of ‘modernism,’ itself associated with Art Deco, became popular on movie sets and further manifested itself in the fashions adopted by female stars.[55] Lucy Fischer has described Art Deco as divided between a longing for the technological and the traditional or ‘primal,’ favoring ‘stark, high-tech façades, color…reduced to the basics: black, white, and silver. Deco was tied to the modern city….’[56] In addition, Art Deco also ‘courted the Exotic,’ strongly associated with southeast Asia and the Pacific.

However, as has been copiously argued, Hollywood failed to introduce audiences isolated by geographical location to a wider world in any meaningful way, with its ‘films expressing more about American culture than the primitive cultures that fascinate[d] them.’[57] Imperialist fantasies became integrally a feature of golden-era Hollywood film, most visibly in films situated in southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Such films responded to a taste for Asia, but they offered audiences a bizarre Hollywood version of eastern cultures: romanticized landscapes of southeast-Asian rubber plantations, beautiful saronged Polynesian women, and the lazy eroticism of colonial life in the Pacific. Such films folded together exoticism and imperialism, making ‘the American colonial endeavor’ attractive to film audiences partly through ‘half-Caucasian women who further Europeanized Western notions of Islander women.’[58] Edward Said has trained two or three generations of scholars on how to read ‘Orientalisms’ in literature, art, and film. Along with the closely related concept of exoticism, Orientalism encodes attraction to an eroticized Other, and both have been fixtures in western thought for centuries. As Slavoj Žižek has noted, the structure ‘allows us to grasp the unity of human species, to recognize the Other, while nonetheless asserting our superiority’ because ‘the fetishized Other is always “lower”—that is to say, the notion of fetishism is strictly correlative to the gaze of the observer who approaches the “primitive” community from the outside.’[59]

Returning to cheekbones as a signifier of beauty, in this case – exotic beauty – once again, a perusal of fan magazines of the period confirms the observation: page after page of glamor shots of stars with prominent bone structures draped in rich but austerely cut evening gowns are featured side by side with dark-haired women in vaguely Asian-style formal wear. Sarah Berry notes that European stars Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, and Lil Dagover, all renowned for their cheekbones, were ‘“Orientalized” in many films.’[60]

|

|

| Marlene Dietrich | Lil Dagover |

Guides to applying make-up make the link between high cheekbones and this ‘oriental’ look explicit. Carolyn Van Wyck addresses women seeking such an appearance: ‘If you’ve been wondering how Dietrich gets that lovely exotic high-cheekboned look, here’s how it’s done. You highlight your cheekbones with the lighter foundation and then shadow underneath them with the darker foundation. Put the dark foundation on in a triangle and your cheekbone: will look positively Oriental.’[61]

But the performance of ethnicity, which encoded sexual desire and aroused pleasure, also incited a moral panic over the possibility of ‘mixing’ the ‘races,’ leading to what has been called ‘pale exoticism.’[62] Only white female actors could star as exotic beauties, or to be clear, only they could play the love interest of a white male actor. Sarah Berry has shown how golden-era Hollywood dealt with the ‘nativist backlash against immigration aimed at both Asians and the “new immigrants”—Jewish, Italian, and Eastern Europeans’ who were perceived, in contrast with earlier Anglo, German, and Nordic immigrants, as ‘unfit to assimilate into a nativist-defined American identity, which was in danger of being “mongrelized.”’[63] The film industry, she explains, imagined ethnicity in hierarchical categories, with European at the top, and certain ethnicities imagined as ‘racially’ distinct from and inferior to the ‘white’ race.[64] Dutifully translating the series of laws against intermarriage passed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into the infamous Hollywood film codes, the industry prohibited filming happy romances between members of different ‘races.’ This meant, for example, that Chinese or Japanese characters could not be paired with white characters. The construction of whiteness reflected in and formed by Hollywood cinema excluded certain ethnicities even as it eradicated the differences among others and ‘ensured their successful assimilation into an imagined white mainstream structured around core values of Anglo-American culture.’[65]

Moreover, even when there was no question of a romantic relationship, white female actors were preferred over Asian female actors to play Asian women, made up in a style derisively known today as ‘yellowface.’[66] Perhaps the most notorious example is the casting of Luise Rainer over Anna May Wong to play O-Lan in the film version of The Good Earth (1937). Rainer went on to win an Oscar for her portrayal.[67] In a similar vein, Delia Malia Caporoso Konzett describes King Vidor’s casting choices in the 1932 film Bird of Paradise as a betrayal of authenticity that accommodated ‘Hollywood’s prevalent Jim Crow practices by not offending the sensibilities of its mainstream audiences and their apartheid codes of social interaction.’[68] Instead of people whose ethnicities matched those of the characters, Vidor ‘settled for the common practice of casting roles of nonwhite characters with stand-in performances of fetishized and more acceptable ethnic actors,’ giving the female Polynesian lead to Latina Dolores del Rio.

In the same vein, the red-headed American actor Myrna Loy began her career as the ‘paradigmatic “Oriental siren”’ before transitioning to portraying glamorous white women.[69] As a ‘distinctly unusual and Oriental type’ beauty, Loy cashed in on her ‘new exotic type vamp’ look into the 1930s.[70] But she was ambitious: the type, although a fixture in Hollywood, was almost never the starring role, and Loy insisted on moving on. Regarding this career move, fan magazines attribute her with ‘a significant degree of agency and control over the construction of her onscreen image and identity,’ writes James Castonguay.[71] Loy herself explains her transformation as strategic and credits her own hard work. Not wanting to remain mired in the bit-player status to which the type relegated her, she chose to refashion herself: ‘The only thing left for me to do I decided was to think up a new self and then to be it.’[72] Above all, she confides in Hollywood magazine, ‘I’m glad that I was born homely.’

Whether it’s a career—or a man—I honestly believe that the girl who is born homely has a better chance to get what she wants than the girl who is born beautiful. For this reason: The girl who is born homely learns very early in life that if she wants her share of the world’s plums she can’t sit idly by and wait for them to fall into her lap. She has to get out and shake the tree.[73]

Although an environment of easily donned and doffed ethnicities would seem at first glance to have offered the perfect context for actors of different backgrounds to enter the industry, fluidity of ethnicity was permitted only to white actors. True, Merle Oberon, best known today for her role as Cathy in Wuthering Heights (1939), was able to subvert the process. Oberon, bi-racial daughter of a 12-year-old girl of Sri Lankan and Māori descent raped by the Anglo-Irish foreman of a tea plantation, grew up in India.[74] How did an actor whose ethnicity should have excluded her from leading lady roles opposite a white actor according to the infamous code become one of Hollywood’s leading ladies? She accomplished the feat only at great cost to herself by hiding her origins – her story coming out officially only after her death.[75] According to journalist Meryl Sebastian, ‘as a star in Hollywood’s Golden Age, [Oberon] kept her background a secret—passing herself off as white—throughout her life.’ Specifically, Oberon presented herself as ‘an upper-class girl from Hobart [in Tasmania] who moved to India after her father died in a hunting accident.’

Merle Oberon

Tasmania seems to have represented an ‘exotic’ locale in the minds of American and European audiences, but it was also perceived as very British. Sebastian writes that the trick worked so well that it convinced Tasmanians to the extent that Oberon was embraced as a native daughter.[76]

Believing Oberon to be white, her audiences appreciated her ‘exotic’ look. Life magazine asserts that Oberon’s ‘romantic’ Tasmanian origin, ‘coupled with her high cheekbones, inspired her first employers to cast her in Oriental make-up.’[77] Fan magazines emphasize that the star looked Asian, although they believed that she was not. In a 1935 issue of Picture Play magazine she is referred to as ‘Asiatic-looking Merle Oberon’ as she pauses ‘momentarily on her way to Hollywood from London’[78] and, in another, as looking like an ‘Asiatic princess with Paris polish.’[79] Furthermore, another issue of the same year, entitled ‘Lost—Oberon the Exotic,’ specifically focused on Oberon’s ability to shift ethnicity. But bizarrely, Oberon’s exoticism was understood as the act, her Englishness as the reality. The article describes her reverting from a ‘beautiful exotic’ back into a ‘fresh-faced English girl.’[80] In place of the ‘most glamorous siren in years,’ Oberon gives us ‘who she is,’ an English girl, her ‘lure intensified because of its naturalness.’

Myrna Loy

Oberon’s fluid identity, both familiar and foreign, was perfectly suited to Hollywood as long as she hid the truth about her parents. In contrast to Oberon’s experience, Chinese-American Anna May Wong was precluded from the assimilation that would have permitted her stardom. Wong, too, seemed perfectly positioned for such a career, representing both the familiar and the ‘exotic,’ that is, the approachable beauty of American daily life promoted by fan magazines and the otherness of Oriental sophistication.[81] Her face boasted ‘the lure of evasive Oriental beauty’[82] and ‘her high cheekbones, heavy-lidded eyes and lovely smile had made her popularly known as “the world’s most beautiful Chinese girl.’”[83]

Anna May Wong

Her prominent bones under luminous ivory skin and ‘large’ eyes were gifts from the gods. One reviewer’s vocabulary failed him, he writes, in trying to describe Wong’s ‘hallucinating beauty and charm.’[84] She symbolized the ‘eternal paradox of her ancient race,’ evoking at once ‘intimate intrigues’ and ‘crooned Chinese lullabies.’[85]

But whereas Oberon occulted her ethnic identity, Wong either could not or would not do so and was shut out of lead roles. Strictly as a matter of appearance, Wong might have been cast alongside a ‘white’ actor as, say, a Polynesian leading lady; as the code specified, the ‘union of a member of the Polynesian and allied races of the island groups with a member of the white race is not ordinarily considered a miscegenetic relationship.’[86]

Anna May Wong and Ramon Novarro, not allowed to kiss!

But Hollywood insisted on her ‘authentic Chineseness,’ thereby rendering her ineligible to play ‘exotic’ lead roles of indeterminate ethnicity.[87] Permanently associated with her Chinese identity, Wong, who never set foot in China until 1936, could not switch back and forth between ‘races,’ that is, from Chinese to Polynesian.[88]

Oberon and Wong and their cheekbones reveal how incoherent Hollywood notions of race always were, as well as how easily the early film industry might have told a different story. Beauty standards inevitably intersect with a society’s conceptions of race: both are presumably visible at a glance and central to personal identity. Golden-era Hollywood, demonstrating that both could be created by a make-up artist, might have worked toward dislodging or at least disrupting American racism by showing race to be an illusion. After all, the very premise of the film industry was and is the creation of illusion. And yet, the industry’s relationship with illusion was hopelessly bifurcated. On the one hand, cheekbones, like beauty and race, were externally applied – produced by cosmetics. In this context, cheekbones represented inclusivity and access for everyone to exciting other worlds. Theoretically, possessing beautifully sculpted cheekbones should have guaranteed the owner entrance to Hollywood, whatever her race. The catch was, on the other hand, that cheekbones, beauty, and race were also innate, unchanging, and present at birth.

The latter version of race was under constant threat from the illusions that the industry created every day. Merle Oberon, of Sri Lankan and Māori descent, looked like a ‘natural’ English girl and functioned as one because no one knew the ‘inner’ truth. The Chinese-American woman whose very name, Anna May Wong, declared her race could never assume a different identity because her secret was already out. The emphasis that Hollywood placed on cheekbones – a feature of both external and internal dimensions – encoded the feature’s incoherent duality.

[1] The past few years have seen a number of important studies on the beauty-industrial complex: what it is, and how it functions. For overviews and case studies, see the collection Sarpila, Outi et al. (eds.) Appearance as Capital: The Normative Regulation of Aesthetic Capital Accumulation and Conversion (Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2021), Laham, Martha. Made Up: How the Beauty Industry Manipulates Consumers, Preys on Women’s Insecurities, and Promotes Unattainable Beauty Standards (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020), and Elias, Ana Sofia, Rosalind Gill, and Christina Scharff (eds.) Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). Also, refer to the iconic: Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), which remains relevant.

[2] For an idea of what is meant by white beauty culture, see Pereira, Malin. Embodying Beauty: Twentieth-Century American Women Writers’ Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2021). This was first published in 2000. Refer to 65–84. Moreover, refer to Henderson, Carole (ed.). Imagining the Black Female Body: Reconciling Image in Print and Visual Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) and Walker, Susannah. Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007), especially 11–26.

[3] Shen, Hui et al. ‘Brain responses to facial attractiveness induced by facial proportions: evidence from an fMRI study,’ Scientific Reports, 6: 35905, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35905. The notion of female facial beauty as a sign of health and, therefore, as an adaptation facilitating reproduction, fascinates evolutionary psychologists. See Hönn, Mirjam and Gernot Göz. ‘The Ideal of Facial Beauty: A Review,’ Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics, 68:1, 2007, 6–16; Johnston, V.S. ‘Mate Choice Decisions: The Role of Facial Beauty,’ Trends in Cognitive Science, 10:1, 2006, 9–13; Zaidel, D.W., S. M. Aarde, and K. Baig. ‘Appearance of Symmetry, Beauty, and Health in Human Faces,’ Brain Cognition, 57:3, 2005, 261–3; Perrett, D. I., K. A. May, and S. Yoshikawa. ‘Facial shape and judgements of female attractiveness,’ Nature, 368:6468, 1994, 239–42; Baudouin, JY. and G. Tiberghien. ‘Symmetry, Averageness, and Feature Size in the Facial Attractiveness of Women,’ Acta Psychologica, 117:3, 2004, 325. However, the correlation between facial features and health is weak. See Rhodes, Gillian. ‘The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty,’ Annual Review of Psychology, 57:1, 2006, 215.

[4] See, for example, Samizadeh Souphiyeh and Woffles Wu. ‘Ideals of Facial Beauty Amongst the Chinese Population: Results from a Large National Survey,’ Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 42:6, 2018, 1540–1550. The authors demonstrate the Chinese preference for an oval face shape. They conclude that ‘across all human cultures characteristics such as averageness, symmetry, harmony, and balance are key features of perceived attractiveness and facial beauty,’ but the preferred size and shape of various features differ.

See also Zhan, Jiayu et al. ‘Modeling individual preferences reveals that face beauty is not universally perceived across cultures,’ Current Biology, 31:10, 2021, 2243–2252; Blais, Caroline et al. ‘Culture Shapes How We Look at Faces,’ PLoS ONE, 3:8, 2008; and Coy, Katie. ‘Chinese Beauty Standards (in 2022) vs The West,’ LTL Mandarin School, 24 February, 2022. https://www.ltl-shanghai.com/chinese-beauty-standards/#chapter-3. Accessed date.

[5] And, in children, Konrad Lorenz’s ‘Kindchenschema’ (baby scheme) – the large round head with large, widely-spaced eyes and small nose and mouth that some evolutionary psychologists believe to have evolved to arouse parenting instincts – may be universally appreciated. For a recent testing of the ‘Kindchenschema’ see Glocker, Melanie L. et al. ‘Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults,’ Ethology, 115:3, 2009, 257–63. However, it is important to note that participants in the experiment were all students at the same university, and their responses cannot be said to represent a universal preference.

[6] The Lantern website, a search platform for the collections of the Media History Digital Library, offers access to hundreds of golden-era Hollywood fan magazines. https://lantern.mediahist.org/.

[7] See Chaleila, Wisam Abughosh. Racism and Xenophobia in Early Twentieth-Century American Fiction: When a House is Not a Home (New York: Routledge, 2021); the anthology Gordon-Reed, Annette et al. Racism in America: A Reader (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020); Lee, Erika. America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2019); Kendi, Ibrahim. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (London: Random House, 2016). On racism toward Asians in the United States see Aoki, Andrew and Okiyoshi Takeda. Asian American Politics (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008), 1–22; Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Salyer, Lucy. Laws Harsh As Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000). For racism in Hollywood in particular see Courtney, Susan. Hollywood Fantasies of Miscegenation: Spectacular Narratives of Gender and Race, 1903-1967 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

[8] The context is Finck’s discussion of populations that consider high cheekbones beautiful: Mongolian, North American Indian, ‘Eskimo,’ and ‘Siamese’ in Finck, Henry T. Romantic Love and Personal Beauty: Their Development, Causal Relations, Historic and National Peculiarities, vol.II (London: Macmillan and Company, 1887), 423.

[9] Finck, 1887, vol.II, 423–24.

[11] McMein, Neysa. ‘The Six Most Beautiful Women of the Screen,’ Motion Picture Magazine 25, May 1923, 29.

[12] ‘Letters to the Editor,’ Motion Picture Magazine 26, August 1923, 110.

[13] Van Wyck, Carolyn. ‘Friendly Advice,’Photoplay 28, June 1925, 120.

[14] Scott, A.O. ‘The Pictures, the Face,’ The New York Times Magazine (November 12, 2000): 64.

[15] Bainbridge, John. ‘Path to Stardom, Even her Very Soul,’ Life, 17 January 1955, 78.

[16] Smith, Zadie. ‘Nature’s work of art,’ The Guardian, 15 September 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2005/sep/15/film.zadiesmith. Accessed 15 July 2023.

[18] Scott, A.O. ‘The Pictures, the Face,’ The New York Times Magazine (November 12, 2000): 64.

[19] For details about Hollywood fan magazines, refer to Slide, Anthony. Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine: A History of Star Makers, Fabricators, and Gossip Mongers (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2010).

[20] Temple, Mary. ‘She Stole His Best Scenes.’ Photoplay 43, January 1933, 116.

[21] Lynn, Hilary. ‘Thing called “X”,’Photoplay 43, April 1933, 90.

[22] ‘The Audience Talks Back,’ Photoplay 44, September 1933, 14.

[23] Zeitlin, Ida. ‘The Battle is On!’ Screenland 29, June 1934, 75.

[24] ‘Boos and Bouquets,’ Photoplay 53, January 1938, 87.

[25] Lejeune, C.A. ‘Gable’s Got Her!’ Modern Screen 34, March 1947, 94.

[26] Craig Greene, Alice. ‘The Miracle of Valli,’ Movieland 5, November 1947, 33.

[27] York, Cal. ‘Inside Stuff,’Photoplay 42, August 1952, 12.

[28] https://fashionrepublicmagazine.com/high-cheekbones/ . Accessed 15 July 2023.

[29] March, Bridget. ‘The Most Wanted Cheekbones in Harley Street,’ Harper’s Bazaar, 8 December 2008, https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/beauty/skincare/g14380486/most-popular-celebrity-cheekbones/. Accessed Date.

[30] ‘Cheekbones that Changed the World,’ NewBeauty, 24 October 2015, https://www.newbeauty.com/cheekbones-that-changed-the-world/1. Date Accessed.

[31] Berry, Sarah. Screen Style: Fashion and Femininity in 1930s Hollywood (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000a), xii.

[32] Peiss, Kathy. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 114.

[34] Berry, Sarah. ‘Hollywood Exoticism: Cosmetics and Color in the 1930s,’ in Desser, David and Garth S. Jowett (eds). Hollywood Goes Shopping (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000b), 108–138. Pay particular attention to pp.115–116.

[35] Corson, Grace. ‘What Makes Women Beautiful…’Motion Picture Magazine 33, June 1927, 20.

[36] Van Alstyne, Anne. ‘Have you a Beauty Budget?’ Screenland 20, April 1930, 90.

[39] Mack, Grace. ‘Myrna Loy says It Pays To Be Homely,’ Hollywood 24, January 1935, 15.

[40] Van Wyck, Carolyn. ‘Photoplay’s Own Beauty Shop,’ Photoplay 53, March 1938, 8.

[41] Sposa, Louis A. The Television Primer of Production and Design (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1947), 93–4.

[42] Hunt, Mabel. ‘Beauty with the Blues,’ Screenland 36, April 1938, 51.

[43] Lynd, Robert S. and Helen Merrell Lynd. Middletown (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1929), 161, cited in Berry, 2000a, 2.

[44] Cultures accumulate stores of possessions upon which their wealth and prestige are based, ‘inalienable possessions,’ which are ‘imbued with the intrinsic and ineffable identities of their owners which are not easy to give away. Ideally, these inalienable possessions are kept by their owners from one generation to the next within the closed context of family, descent group, or dynasty. The loss of such an inalienable possession diminishes the self and by extension, the group to which the person belongs.’ Weiner, Annette. Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While-Giving (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992), 6.

[45] Armstrong, Rolf. ‘Is This the Perfect Screen Face,’ Screenland 21, September 1930, 18–19.

[46] Factor, Max. ‘Give Yourself a Break in Beauty,’ Hollywood 24, January 1935, 41.

[49] Jones, Idwal. ‘McQuarrie on Make-Up,’ New York Times, 27 November 1938, 172.

[50] Hollywood 24 (March 1935): 29.

[51] Boyd, Ann. ‘Film Test for Beauty,’ The New Movie Magazine 9, April 1934, 60.

[52] ‘Nothing But The Truth,’ The New Movie Magazine 9, April 1934), 27–28.

[53] Screen Actor, Volumes 22-28 (1980): 19.

[54] ‘They Meet Their Close-Up Test Triumphantly,’ Screenland 21, September 1930, 105.

[55] MacKenzie, John M. Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), 90–91.

[56] Fischer, Lucy. ‘Greta Garbo: Fashioning a Star Image,’ in Petro, Patrice (ed.). Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 140.

[57] Fain, Kimberly. Black Hollywood: From Butlers to Superheroes: the Changing Role of African American Men in the Movies (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2015), 33.

[58] Brawley, Sean and Chris Dixon. Hollywood’s South Seas and the Pacific War: Searching for Dorothy Lamour (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 16. See also Fain, 2015, 33–34.

[59] Cited in Caparoso Konzett, Delia Malia. Hollywood’s Hawaii: Race, Nation, and War (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 3. Said’s definition of Orientalism is pertinent, as well. See Said, Edward. Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 2014) 2–4. (First published in 1978)

[60] Berry, 2000b, 111. Garbo and Dietrich’s cheekbones are well-known; for more detail on Dagover’s see Goldbeck, Elisabeth. ‘Meet Europe’s Girlfriend – And America’s Newest Thrill,’ Motion Picture 43 (1932 ): 66.

[62] The expression used in Desser and Jowett (eds.), 2000, 119. See also Berry, 2000b, 193.

[64] Ibid. For detailed discussion, see the collection: Beltrán, Mary and Camilla Fojas (eds.). Mixed Race Hollywood (New York: New York University Press, 2008).

[65] Caparoso Konzett, 2017, 8.

[66] See the articles: Wang, Yiman. ‘Screening Asia: Passing, Performative Translation, and Reconfiguration,’ Positions, 15:2, 2007, 319–343 and Wang, Yiman. ‘Anna May Wong: a Border-crossing “Minor” Star Mediating Performance,’ Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 2:2, 2008, 91–102.

[67] See Desta, Yohana. ‘Hollywood: The True Story of Anna May Wong and The Good Earth,’ Vanity Fair, 1 May 2020, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2020/05/hollywood-ryan-murphy-anna-may-wong. Date Accessed.

[68] Caparoso Konzett, 2017, 2.

[69] Castonguay, James. ‘Myrna Loy and William Powell: The Perfect Screen Couple,’ in McLean, Adrienne L. (ed.). Glamour in a Golden Age: Movie Stars of the 1930s (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 221.

[74] Liebman, Lisa. ‘The Fascinating Old Hollywood Story That Inspired The Last Tycoon’s Best Plotline,’ Vanity Fair, 28 July 2017, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/07/last-tycoon-jennifer-beals-merle-oberon. Date Accessed.

[75] For details about Oberon’s life story, refer to Underwood, Peter. Death in Hollywood (London: Piatkus, 1992), 29–45.

[76] Sebastian, Meryl. ‘Merle Oberon: India’s forgotten Hollywood star,’ BBC News, 16 April 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-61079732. Date Accessed.

[77] “The Newest Movie Queen,” Life (21 December 1936): 46.

[78] Hollis, Karen. ‘They Say in New York,’ Picture Play 41, February 1935, 67.

[79] Hollis, Karen. ‘They Say in New York,’ Picture Play 42, April 1935, 67.

[80] Babcock, Muriel. ‘Lost – Oberon the Exotic,’ Picture Play 43, October 1935.

[81] Leung, Louise. ‘East Meets West,’ Hollywood 27, January 1938, 40 and 55.

[82] ‘Rotogravure,’ Photoplay 27, April 1925, following page 59, no pagination.

[83] Kalmus, Herbert Thomas and Eleanore King Kalmus. Mr. Technicolor (Absecon, NJ: MagicImage Filmbooks, 1993), 43.

[84] De Casseres, Benjamin. ‘The Stage in Review,’ The New Screenland 22, February 1931, 64.

[85] ‘Our Portrait Gallery,’ Motion Picture Magazine 27, April 1924, 21.

[86] As decided by Olga Martin, secretary to Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration. See Brawley, Sean and Chris Dixon. The South Seas: A Reception History from Daniel Defoe to Dorothy Lamour (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015), 238, which cites Olga Martin. For the rule itself see Martin, Olga. Hollywood’s Movie Commandments: A Handbook for Motion Picture Writers and Reviewers (New York: Arno Press, 1937), 178. On the machinations to define different races and decide on what counted as miscegenation, see chapter three, ‘“The un-doable stories,” the “usual answers,” and other “epidermic drama[s]”: coming to terms with the production code,’ in Courtney, 2005, vii.

[87] Wagner, Rob. ‘Better a Laundry,’ Screenland 16, Jan 1928, 82. No uniform code ever existed, but for an interactive set of some of the versions see https://productioncode.dhwritings.com/multipleframes_productioncode.php.

[88] Yiman Wang calls the claim that Wong was in some sense authentically Chinese the ‘mimetic fallacy.’ See Wang, Yiman. ‘Anna May Wong: Towards Janus-faced, Border-crossing, “Minor’ Stardom,’ in Petro, 2010, 159–191.

Tracy Adams is professor in European Languages and Literatures at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. Her most recent books include The Creation of the French Royal Mistress, co-authored with Christine Adams (2020), Agnès Sorel and the French Monarchy (2022), and Queens, Regents, Mistresses: Reflections on Extracting Elite Women’s Stories from Medieval and Early Modern French Narrative Sources (2023).