Ryan Conrad

…history is a process of generalization, an elevator pitch, and we privilege the stories that are easier to tell. In the public sphere, complexities are frequently slipped under the shadows of our zeitgeists, and well-worn media tropes supplant more disorderly truths.

– Avram Finklestein, AIDS 2.0[1]

Introduction

This essay analyzes cultural production by queer American artists in the 1980s and 1990s that frames the AIDS epidemic as a form of genocide, using James Wentzy’s 1994 experimental film By Any Means Necessary as its anchor. Reviving these neglected works will demonstrate how common the analogies between warfare upon civilians, genocide, the Holocaust and the AIDS epidemic were amongst queer cultural producers at the time. Through (re)readings of Paula Treichlar, Susan Sontag, Judith Butler and Deborah Gould, this paper examines how these meaning-making metaphors came to be accepted within the shifting emotional habitus of queer people at the height of the crisis. This essay continues by briefly examining how the AIDS epidemic is being historicized at the present moment, in terms of both its political and affective legacy, through recent film and visual culture. How have these metaphors of mass death and total destruction of queer lives been rearticulated or forgotten and to what ends? Lastly, this essay will offer provisional reflections as to how the historical framing of the AIDS epidemic as genocide does or does not serve the current gay and lesbian political turn towards assimilation, inclusion and respectability. Or more specifically, what does it mean to not remember the AIDS crisis on the terms by which it was described by those queer artists and activists who experienced the carnage and unimaginable loss of life first hand, but are no longer here to remind us? And what do we make of contemporary work produced by those who did survive, but have turned away from these once commonplace metaphors.

Although the AIDS epidemic also disproportionately impacted other marginal groups at its onset—the disabled (hemophiliacs), racialized populations (particularly Haitians), and injection drug users—this essay focuses specifically on queer cultural responses to the crisis because my larger project is to investigate how the legacy of the AIDS crisis had and continues to have an impact on the trajectory of contemporary gay and lesbian politics. While none of these affected groups are mutually exclusive and racialized groups of people remain grossly overrepresented in both incidence and prevalence of HIV infection, the political fortunes of gays and lesbians have rapidly expanded since the invention of the Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Treatment (HAART). Beginning in the mid 1990s the crisis shifted from the stark reality that AIDS was a disease marked by assured death, to a chronic long-term manageable illness for those who could access treatment. While the political fortunes of gays and lesbians rapidly expanded since these so-called post-AIDS years just after the invention of HAART, racialized people, drug users and the disabled remain deeply marginalized in American society. This essay explores this specific impact of AIDS on gay and lesbian politics in part to understand why their political fortunes have grown by leaps and bounds while other disproportionately affected communities remain disenfranchised and in crisis.

Partial Histories and Metaphors in the Making

Doing the history of AIDS in any capacity, including small, specific and somewhat superficial historiographies like the one offered in this essay, always seems to be condemned to high-stakes inaccuracies, partial truths and flattened complexities no matter how hard one tries otherwise. This essay hopes to avoid such missteps to the extent possible when dealing with such fraught and contested past events. Rather, it hopes to contribute to the messy and disorderly truths, even the uncomfortable and conflicting ones, that Finkelstein demands of us when doing the history of AIDS.

As an original member of the Silence = Death project and Gran Fury, Finkelstein observed in early 2013 that ‘it’s likely we’re now witnessing the solidification of the history of AIDS’ in reference to the recent canonization of specific AIDS histories. This observation has since become commonplace as scholars attempt to make sense of the outpouring of work looking back at the history of the AIDS crisis.[2] These scholars are reflecting on art retrospectives like the traveling Art AIDS America exhibition on view in various locations for a year between the fall of 2015 and 2016, the New York Public Library’s fall 2013 to spring 2014 exhibition Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism, the Gran Fury: Read My Lips exhibition at New York University in 2012 and Harvard’s 2009 ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993 exhibition.[3]

Additionally, these scholars are referencing the solidifying of certain AIDS histories through recently released documentary films like Sex in an Epidemic (2010), We Were Here (2011), Vito (2011), How to Survive a Plague (2012), United in Anger: A History of ACT UP (2012) and Uncle Howard (2016) as well as recently released historical dramas like Test (2013), Dallas Buyers Club (2013) and the HBO made-for-TV movie reboot of Larry Kramer’s Normal Heart (2014). While these new works are vital to our historical and present day understanding of the ongoing AIDS epidemic, this essay will focus more sharply on lesser-discussed works produced in the late 1980s and early 1990s that weren’t conceived under a logic of historical story telling and anniversary—like the so-called thirtieth anniversary of AIDS in 2011 which produced an outpouring of nostalgic and commercial interest in HIV/AIDS that will just as quickly wane after the few bucks to be made have been extracted.

Cultural production and artistic works, like those created during the pre-protease inhibitor days of the AIDS epidemic in the United States, generously lend themselves to metaphor. Susan Sontag’s seminal 1978 pre-AIDS text titled Illness and Metaphor provides guidance in understanding how such metaphors might impact the health and well-being of people living with AIDS. She argues against using metaphor to describe illness suggesting that metaphors, particularly military ones, cause psychological and social harm to those afflicted; they detrimentally shift our collective focus away from the rational biomedical discourse and hard science from which treatment and cures are derived. Sontag would go on to write the follow up text, AIDS and Its Metaphors (1989), where she shifts her primary focus from cancer to AIDS while making many of the same arguments against illness metaphors. Between the publication of Sontag’s two texts, feminist communication studies scholar Paula A. Treichler interjects with the convincing argument in the now infamous issue of October magazine on AIDS cultural analysis and activism edited by Douglas Crimp that ‘no matter how much we may desire, with Susan Sontag, to resist treating illness as metaphor, illness is a metaphor.’[4] She continues, ‘…the AIDS epidemic—with its genuine potential for global devastation—is simultaneously an epidemic of a transmissible lethal disease and an epidemic of meanings or signification.’[5] Treichlar goes on at length, citing other scholars who have challenged Sontag’s model of clearing the way of harmful metaphor so that more objective science can lead us, but Sontag’s writing has had a lasting impact on scholarship about AIDS. The work of Eric Rofes (Dry Bones Breathes: Gay Men Creating Post-AIDS Identities and Cultures [1998]) and Jan Zita Grover (North Enough: AIDS and Other Clear-cuts [1997]) come to mind in particular as they fastidiously avoid war and military metaphors about AIDS while employing environmental ones alternatively.

What’s of interest here though, is thinking through not just how the media, politicians, moralists, popular culture and even biomedical science have socially constructed meaning about illnesses such as AIDS historically, but how people living with AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s might have utilized metaphor to make sense of their own illness and lives. Specifically, how might have people living with AIDS in the United States before any form of effective treatments existed, utilized metaphor productively to organize their emotions and fight back in the face of devastating political despair, deadly medical negligence, governmental indifference, and a growing pile of dead bodies comprised of friends and lovers?

James Wentzy, By Any Means Necessary, 1994, Video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Genocide?

James Wentzy’s short experimental film By Any Means Necessary was made in 1994 and first exhibited as part of the MIX New York Lesbian and Gay Experimental Film Festival, now referred to simply as MIX NYC, in that same year.[6] According to a 1996 article from POZ magazine written by the now deceased AIDS activist Kiki Mason, the film was made after Wentzy approached him and requested to use a manifesto he had written for a short film.[7] Mason goes on to describes the manifesto as the text he contributed to an ACT UP action in which a smaller affinity group within ACT UP called The Marys would distribute authentic looking Gay Games brochures with the incendiary text. It just so happened that the 1994 Gay Games in New York City also coincided with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, an event ACT UP wanted to commemorate in juxtaposition to the consumer driven Gay Games, Mason notes. Although Mason expresses ambivalence as to the effectiveness of the fifty thousand brochures printed with his words, which at the time were collectively attributed to ACT UP, but the words themselves have been taken up by another artist (Wentzy), giving them another life and leaving a rich audio visual archive of political feelings from which we can continue to make meaning from the past in this present moment. After searching the finding aids for numerous AIDS related collections to locate an original copy of the spoof Gay Games brochure at the New York Public Library’s archives without luck, it appears that Wentzy’s film is primarily what remains of Mason’s words.

James Wentzy, By Any Means Necessary, 1994, Video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Preceding Wentzy’s By Any Means Necessary is a simulated academy leader where white words on a black background proclaim “ONE AIDS DEATH EVERY 8 MINUTES” as the number of minutes count down by the second. This unique simulated academy leader appears on many direct action documentary videos Wentzy produced, including those featured on his Manhattan-based weekly public access television show, AIDS Community Television.[8] In conversation, Wentzy relayed that he created this academy leader shortly after the ACT UP action that shutdown Grand Central station in 1991 where activists were holding a “One AIDS Death Every 8 Minutes” banner over the arrivals/departures time tables.[9] By employing it here in his experimental short video he is directly linking his creative work aesthetically to the now canonized genre of shoot and run style documentary AIDS activist video that emerged along with increased access to consumer grade video technology in the 1980s and 1990s.[10]

James Wentzy, By Any Means Necessary, 1994, Video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Following the simulated academy leader the screen goes dark before transitioning to a tight close up on the face of a dimly lit mustachioed man standing in the foreground before yet another layer of video that will soon be further revealed. The combination of close up shot and dim lighting allows the viewer to see the glossy reflection of the man’s eyes and the shadowy outline of his face, but not clearly enough to actually identify him. He remains semi-anonymous as anyone would in the dimly lit back rooms of the then shuttered gay sex clubs and bathhouses in New York City.[11] The man slowly begins to deliver the then anonymous manifesto by Kiki Mason in a calm, but sure voice as the camera slowly zooms out revealing the black and white film footage of World War II concentration camps littered with lifeless bodies in the background.

James Wentzy, By Any Means Necessary, 1994, Video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

The manifesto begins:

I am someone with AIDS and I want to live by any means necessary. I am not dying. I am being murdered just as surely as if my body was being tossed into a gas chamber. I am being sold down the river by people within this community who claim to be helping people with AIDS. Hang your heads in shame while I point my finger at you.[12]

The metaphor between AIDS and genocide, and the Holocaust more specifically here, begins at the outset of this spoken manifesto and visually through the pairing of Holocaust imagery with that of a person living with AIDS. This framing of AIDS as genocide and analogies linking AIDS to the Holocaust continues throughout the emotionally dense five minute and forty-nine second video as the following two brief excerpts demonstrate:

Activists now negotiate with drug companies just as the Jewish councils in the Warsaw ghettos of World War II negotiated with the Nazis. ‘Give us a few lives today,’ they insist, ‘and we’ll trade you even more tomorrow.’ AIDS careerists—both HIV-positive and HIV-negative—have exchanged their anger for an invitation to the White House…[13]

Jewish leaders established organizations to run their ghettos and we do the same in a desperate attempt to gain some sense of control over this living nightmare. Everyone is selling you out. We refuse to plead with the US government or negotiate with the entire medical-industrial complex for our lives. We have to get what we need by any means necessary…[14]

The framing of AIDS as war or genocide, and specific references to the Holocaust are not limited to Wentzy’s short video. In fact the metaphorical reference is quite common throughout AIDS related cultural production in the United States created before the invention and large-scale usage of life-saving medication like protease inhibitors as the following examples demonstrate.

The Silence = Death project, a small consciousness raising group that predates the more well known propaganda arm of ACT UP called Gran Fury with whom they are often conflated, designed numerous posters framing AIDS as genocide.[15] They are credited with the creation of the 1986 iconic black poster with a centrally placed inverted pink triangle, a direct reference to the pink triangle worn by homosexual men in Nazi concentration camps, and the white text ‘SILENCE = DEATH’ running along the bottom. They also produced the group’s equally recognizable 1987 neon yellow and pink “AIDSgate” poster of Ronald Reagan with fiendishly neon pink eyes and includes the caption ‘…What is Reagan’s real policy on AIDS? Genocide of all non-whites, non-males, non-heterosexuals?…’[16]

Members of the Silence = Death project also contributed to an installation in 1987 titled ‘Let the Record Show’ in which ‘AIDS criminals’—doctors, politicians, journalists—are shown before a backdrop of the Nazi Nuremberg trials, again making the connection between AIDS, and WWII and the Holocaust.

AA Bronson of the renowned queer Canadian artist collective General Idea describes the process of making a portrait of one of his dying collaborators titled Jorge, February 3, 1994 in the 2008 documentary General Idea: Art, AIDS, and the Fin de Siècle. In it Bronson states,

This was a portrait, three portraits I guess, of Jorge [Zontal] that I took about a week before he died. His father had been a survivor from Auschwitz and he had this idea that he looked much as his father had looked when he came out of Auschwitz. He’s blind here and he asked me to take these pictures to document that. So when I finally produced them as a piece, I printed them in sepia on Mylar so they have this sense of memory to them and it’s interesting how vivid that echo back to Auschwitz is. This piece is in fact in the collection of the Jewish Museum in New York.[17]

Although General Idea was originally based in the fledgling Toronto art scene of the late 1960s, the collective would soon split their time between New York City and Toronto before their demise in 1994 due to the deaths of all members except Bronson.[18] They are included amongst the other American cultural workers here as they were influenced by their time in the politicized art milieu of New York City and their work is clearly in dialog with other American artists working during this time period.

Musician and activist Michael Callen, an HIV-positive gay man and the founder of the People Living with AIDS Coalition, produced a pop album titled Purple Heart in 1988.[19] The title of this thematically AIDS focused album references the medal earned by active duty United States military personnel injured or killed in battle. Metaphorically, Callen is suggesting that this is also a medal that should be awarded to people living with AIDS if AIDS was indeed a war being waged against HIV-positive people, particularly the so-called undesirables who felt most under siege: queers, injection drug users, poor people, disabled people and people of color. Additionally, according to artist and AIDS activist Gregg Bordowitz, the track Living in War Time that appears on Callen’s Purple Heart album serves as the soundtrack that structures one of the earliest direct action AIDS activist video documentaries, Testing the Limits: NYC (1987).[20] Callen also covers Elton John’s 1970 piano ballad Talking Old Soldiers, imbuing it with new meaning as an homage to the first generation of gay men and activists of which Callen was a part, who are already war weary from the ongoing battle against AIDS.

A longer iteration of Testing the Limits: NYC was produced four years later by the same collective titled Voices from the Front (1991). This video documentary aired on HBO in October 1992 and featured segments where activists discussed opposition to the proposed laws to quarantine and tattoo HIV positive individuals. This documentary also included an interviewee who made the argument that not including people of color in medical trials was equal to genocide.

The war metaphors continue with the Red Ribbon project that was produced through an affinity group within Visual AIDS Artists’ Caucus. The Red Ribbon, now a ubiquitous and arguably politically innocuous international symbol was originally designed to mimic the yellow ‘support our troops’ ribbons popularized during the United States invasion during the Gulf War in the early 1990s.[21] Or as one of the founding members Robert Atkin’s put it, ‘the Artists’ Caucus produced the [Red] Ribbon to subvert the onslaught of gooey jingoism unleashed by the Gulf War and embodied in the yellow ribbon.’[22]

These sentiments are echoed in echoed in the cultural interventions undertaken during one of ACT UP/NYC’s coordinated days of action known as the Day of Desperation on January 23rd 1991. The night before the big day of action, John Weir, a novelist, cultural critic and activist, snuck into the CBS news studios in New York City along with two other activists and interrupted a live broadcast of the evening news with Dan Rather. Weir, popping on screen briefly shouting ‘Fight AIDS not Arabs!’ was articulating a connection between the war abroad and the unaddressed AIDS war at home.[23] Further stressing the links between George Bush Senior’s gulf war and the AIDS crisis in the United States, ACT UP/NYC performed a massive takeover of Grand Central Station releasing a banner affixed with helium balloons that read ‘Money for AIDS, Not for War.’ Neither of these interventions explicitly makes the connection between war, genocide and holocaust as clearly as the banner carried by ACT UP at San Francisco’s Pride Parade in 1990 that read ‘AIDS = GENOCIDE, SILENCE = DEATH,’ but it’s clear that AIDS and war are seen on equal footing and easily comparable through the interventions undertaken as part of ACT UP/NYC’s day of desperation.[24]

Two of L.A.-based Gregg Araki films from the early 1990s also portray characters describing the AIDS crisis as genocide. ‘I think it’s [AIDS] all part of the neo-Nazi Republican final solution. Germ warfare you know? Genocide’ claims Luke in the Araki’s self-proclaimed ‘irresponsible’ road movie, The Living End (1992). ‘It’s government sponsored genocide, biological warfare, I mean think about it. A deadly virus that is only spread through premarital sex and needle drugs, it’s like a born again Nazi republican wet dream come true,’ says Michelle in Totally Fucked Up (1993) to which Patricia adds, ‘AIDS will go down in history as one of the worst holocausts ever. I mean America is committing genocide against it’s own people and eventually this plague’s gonna rack up more causalities than Hiroshima and Hitler combined. And nobody will ever forgive our lame shit government for just sitting back and letting it happen.’ In the production notes enclosed in the DVD release of The Living End Araki again despondently explains,

In the back of my mind, I was sort of hoping that by the time The Living End was finally released, the AIDS holocaust would be over and the movie would be something of an anachronism. Unfortunately, given our present day sociocultural climate of rightwing oppression and rampant gaybashing, it seems even more relevant now than when it was written [1988] over three years ago.

David Wojnarowicz’s performance poetry and visual works also include comparisons between the Holocaust and AIDS. In his collage piece Untitled (If I had a dollar…) 1988-89 he refers to politicians and government healthcare officials as ‘thinly disguised walking swastikas.’ This line is repeated in spoken word performances featured in his own 1991 video collaboration ITSOFOMO with Ben Neil. This same piece of performance poetry was also used in an unfinished video collaboration between Wojnarowicz and Diamanda Galás called Fire in My Belly (1989) that was excerpted and re-edited for German filmmaker Rosa von Praunheim’s documentary, titled Silence = Death (1990), on the impact of the AIDS crisis on New York City artists. In another photographic work titled Subspecies Helms Senatorius (1990) Wojnarowicz has taken a photo of a plastic spider with a swastika painted on its back and conservative politician Jesse Helm’s face collaged onto where the spiders face should be.

Returning to Von Praunheim’s videoworks, the Silence = Death documentary mentioned previously also opens with a videotaped performance by the punk rock performer Emilio Cubiero of his spoken word piece The Death of An Asshole (1989). In this piece he explicitly refers to AIDS as germ warfare before delivering a blistering diatribe against having had war declared on him ‘and this whole group of people [gays].’ He finishes with a screed against AIDS victimhood and takes control of his own life by inserting a pistol into his asshole and pulling the trigger thereby killing himself.

Praunheim’s other documentary titled Positive (1991) released the same year focused more on New York City’s gay activist milieu fighting the AIDS epidemic. In this documentary Praunheim includes a brief interview with gay Jewish activist and writer Arnold Kantrowitz who explicitly broaches the topic of comparisons between the AIDS crisis and the Holocaust. In Kantrowitz’s mediation on the subject he notes how some people take offense to AIDS-Holocaust metaphors, but that in his research and self-education about the Holocaust he sees many legitimate points of comparison including the disappearances of many friends and acquaintances, the general public not caring, the relief exhibited by homophobes that homosexuals were going away—a similar relief to that exhibited by anti-semites during the Holocaust—, that many were killed in a short time, and that there was a great loss of contributions to the arts and philosophy due to the death of so many creative gay people and gay intellectuals. The documentary ends with an interview on the street at a Pride festival in New York City with a man named Marty who emphatically states to the camera that AIDS was the Pearl Harbor of gay liberation. To hammer home the analogy further, a quote from playwright and AIDS activist Larry Kramer adorns the cover of the VHS release from First Run Features proclaiming: ‘this is our Holocaust, New York City is our Auschwitz, Ronald Reagan is our Hitler.’

Critically acclaimed gay playwright Tony Kushner may be most well know for his Pulitzer Prize-winning play Angels in America (1993) that was given the full made-for-television HBO treatment in 2003, but his 1987 play A Bright Room Called Day is also noteworthy. In this play, set in both the inter-war years of the Weimar Republic and the 1980s in New York City, Kushner clearly compares Hitler’s rise to Reagan’s amongst thinly veiled references to the AIDS crisis. This comparison caused outrage amongst theater critics at the time of its production and is largely overshadowed by the success of Angels in America.[25]

Felix Gonzalez-Torres also carries the Nazi Holocaust metaphor throughout a series of untitled works in the late 1980s, often featuring family portraits of Nazi leaders in jigsaw puzzle form. Also of note amongst this collection of untitled works is the piece Untitled (1987) which is a photostat with Gonzalez-Torres’s signature date-list. This piece starts with ‘Bitburg Cemetery 1985,’ referencing Reagan’s ceremonial visit to the graves of Waffen-SS Nazi soldiers at the request of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl in order to demonstrate the repaired friendship between the United States and Germany after World War II.

Taking theatrical protests to new levels of ridiculousness, the anonymous collective of AIDS activists known as Stiff Sheets utilized the Holocaust metaphor twice at their January 1989 AIDS fashion show that coincided with the week-long protest vigil outside L.A. County/University of Southern California Medical Center.[26] As seen in John Goss’s 1989 documentary of the event, one person is modeling a night gown complete with a pink triangle and identification number printed directly on it, invoking the style of ‘concentration camp chic.’ The MC of the event lets everyone know they should order theirs today, before the grand opening of Auschwitz-Anaheim where they will all be transferred in the spring. After all the AIDS inspired ensembles have been shown off before a raucous crowd, the ‘Parade of Homophobes’ follows. In this final segment activists march down the red carpet runway with oversized cut outs of the busts of notorious serophobic homophobes. Included amongst Ronald Reagan, Jesse Helms, Lyndon LaRouche, Jerry Fallwell, and a few other notorious contemporary enemies of people living with AIDS, is Adolf Hitler.

I provide this detailed list of visual and performative work from the United States that makes the metaphoric connection between the AIDS crisis and war, the Holocaust, and genocide not to belabor my point, but to show how the analogy circulated in common usage across artistic disciplines amongst queer cultural producers at the time. This is not to elide the differences in specificity between genocide, war and the Holocaust, or to even argue that these were the only metaphors in usage amongst American artists making work about the AIDS crisis, but this brief overview of artistic and cultural works makes clear that such a cluster of metaphors was in broad circulation and these works were not isolated in their metaphoric invocations.

It is also important to note that many—but certainly not all—of these queer cultural workers surveyed previously are both Jewish and based in New York City. These artists were also contending with the ongoing historification of the Holocaust punctuated at the time by the Broadway production of Martin Sherman’s play Bent in 1980, which examines the Nazi persecution of homosexuals, as well as the release of Claude Lanzmann’s epic nine-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah in 1985. For young queer and/or Jewish artists living in the United States, the historification and passing on of cultural memories of the Holocaust from older to younger generations are inescapable; they clearly had an influence on the way these cultural workers understood the AIDS crisis in relation to their other identities. With AIDS killing people by the thousands and a number of American politicians responding to the crisis by proposing laws for mandatory testing, quarantine, and tattooing of those infected, the analogy seemingly becomes unavoidable.[27]

It should also be noted that the taking up and general usage of Holocaust and genocide metaphors in relation to the AIDS crisis is particularly American. While surveying the queer cultural works of other western countries with similar epidemiological profiles to the United States, it is hard to find similar metaphorical assertions. This could be in part due to the United States’ large Jewish population that fled a hostile Europe before, during and after World War II, with the highest concentration residing in and around the largest epicenter of the AIDS crisis in America, New York City.[28] Furthermore, The United States has the second largest Jewish population in the world. Also at play in the amplification of the genocide/holocaust metaphor in America is the complete absence of a national health care system. These two key factors together likely contribute to the circulation and resonance of the genocide/holocaust metaphor in the Unites States in relation to the AIDS crisis, but as Roger Hallas has demonstrated in his treatise on AIDS, the queer moving image, and witnessing, other historical traumas have been invoked by different constituencies of gay men trying to make sense of the AIDS crisis the world over including the Holocaust, American slavery, Australian anti-immigrant violence and apartheid in South Africa.[29]

Although two Australian artists utilize similar holocaust and genocide metaphors, these pieces come from artists influenced by American artists and or American media. David McDiarmid’s Kiss of Light series uses swastikas in multiple works that he produced just a few years after his tenure in New York City where he mingled with ACT UP activists and from where many of the previous artists mentioned were based. Despite the fact that the references in the exhibition catalog for the recent retrospective When This You See Remember Me (2014) only mention the swastika’s pre-Nazi spiritual uses and meanings, it’s hard not to make the connection to these other artists making much different meanings from the same symbols. Secondly, Christos Tsiolkas’ debut 1995 novel Loaded also features Ari, a young poofter protagonist who lists ‘war, disease, murder, AIDS, genocide, Holocaust, famine…’ in one breath, nihilistically explaining how and why we are all essentially screwed. These two examples do not, however, represent the larger cultural milieu’s response to or structures of feeling regarding the AIDS crisis throughout the industrialized west outside the United States.

Lastly, in situating the AIDS genocide/Holocaust analogy in relation to longer view of queer history and politics, it is helpful to reflect upon how the Holocaust and Nazi references came to occupy a place in gay liberation consciousness before the AIDS crisis. Historian Jim Downs has mapped this out in his writing on gay liberation newspapers like Fag Rag, the Body Politic, Gay Sunshine, Gay Community News, and others, that discussion of the Nazi persecution of homosexuals was common.[30] Downs convincingly argues that these gay liberation papers from the 1970s illuminate the ways in which gay people tried to historically situate gay culture in order to make sense of their present day situation. This was accomplished through the publishing of articles that historicized events like the emergence and crushing of Magnus Hirschfield’s same-sex friendly Scientific Humanitarian Committee in Germany to the experience of gay men and lesbians in concentration camps in Central and Eastern Europe. This history allowed readers and fellow writers to draw analogies between their lives to the lives of an imagined gay community of the past, setting the stage for the explosion of Holocaust/genocide metaphors the next decade as the political crisis of HIV/AIDS emerged. While much ink has rightfully been spilled discussing how or why the Holocaust has become the event to which acts of government suppression and violence are compared to today, as opposed to the many other genocides, taking into account the specificity and genealogy of the Holocaust and its repercussions on queer people offers an understanding of this phenomenon that is specific as opposed to overly generalized.[31]

Returning to Wentzy’s short film, after framing the AIDS epidemic as genocide, Mason’s words turn ever more towards demanding radical action while the video of concentration camp carnage in the background becomes more and more visible. While the anonymous man narrating on screen suggests radical actions like holding drug company executives hostage, splattering blood on politicians, trashing AIDS researchers’ homes and spitting in the face of television reporters, we see bulldozers pushing heaps of lifeless bodies into mass graves and deteriorating body parts strewn about. Although the anonymous man demands these actions he acknowledges that most, including himself, find it difficult to conjure the courage necessary to carry out such action. He concludes by calling upon heterosexual and HIV-negative allies to join the fight and for queers to utilize their queerest gift—creativity—to discover new ways to fight the battle against their continued genocide. In the final seconds of the video the man slowly moves off-screen rendering the background footage fully visible as a limp decomposing body is slowly pulled from a mass grave.

James Wentzy, By Any Means Necessary, 1994, Video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Framing Genocide and the Politics of Emotions

Jim Hubbard, a co-founder of the MIXNYC film festival and long time colleague of James Wentzy, recently exhibited two of Wentzy’s films at the Fales Library at New York University as part of Not only this, but ‘New language beckons us’, a 2013 exhibition on AIDS histories. In Hubbard’s curatorial statement he refers explicitly to By Any Means Necessary outlining his wariness, as a Jew, of making analogies between AIDS and the Holocaust—a wariness he notes that is often expressed by others. He goes on to say, ‘but James Wentzy by combining the physicality of the imagery and the cold-bloodedness of the narration forces me to recognize the connections between mass death from a preventable epidemic and mass death in the gas chamber.

This controversial, yet largely employed framing of AIDS as genocide in the late 1980s and 1990s by activists and artists alike is a clear indication of the shifting emotional state of gay and lesbian people facing the onslaught of a seemingly unending deadly epidemic. Deborah Gould points out that this framing did not resonate emotionally or instigate the necessary political organizing amongst gays and lesbians when Larry Kramer first penned ‘1,112 and counting’ in the New York Native using a genocide framework with Holocaust metaphors for understanding AIDS in 1983.[32] She notes however, that by the late 1980s the AIDS as genocide framework began to resonate emotionally and politically with gays and lesbians in ways it had not before. Gould accounts for this shifting emotional habitus—the embodied, somewhat unconscious emotional disposition of a group formed through social and political forces—of gay and lesbians in the late 1980s in convincing detail. Summarizing her own points she says,

…given a context of immense and apparently intentional government neglect, popular and legislative support for quarantine, denial of basic civil rights by the Supreme Court [Hardwick vs Bowers], media hysteria, and horrific illness and ever-increasing deaths, lesbians and gay men no longer saw it as farfetched to compare thousands of death from a virus with the millions of death due to intentional state murder.[33]

Discussing the implications of framing further, Judith Butler argues in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (2010) that,

Ungrievable lives are those that cannot be lost, and cannot be destroyed, because they already inhabit a lost and destroyed zone; they are ontologically and from the start already lost and destroyed which means that when they are destroyed in war, nothing is destroyed.[34]

Although Butler’s concern in this text is the way the United States government frames and justifies the ongoing war on terror from the top down, it is instructive to think through the possible ways her theorizing about framing could be applied to the bottom up framing of AIDS as genocide by queer artists and activists. If the AIDS epidemic was indeed a war between those with and those without state power as so many queers claimed, does that make queers—again amongst other so-called undesirables—ungrievable subjects as far as the United States government, the medical establishment and the so-called general population was concerned? Could the framing of the AIDS epidemic by queer artists and activists as genocide then be understood as an attempt to reframe the crisis in a way that contests the subject position of queers as ungrievable by tapping into the emotional responses related to a familiar ‘indisputable instance of immorality’ like the Holocaust.[35] Could the genocide framework also be used by queers to make a moral argument for the right to grieve on a massively public and political scale?[36] Was the much-contested term ‘genocide’ a helpful mechanism through which queers could contest their precarity, tap into a well of strong emotional responses, and mobilize against the deadly complicity of government, medical establishment, and the so-called general population?

In an exchange between David Kazanjian and Marc Nichanian over what the term ‘genocide’ does and does not do in relation to the still unacknowledged Armenian Catastrophe/genocide, Kazanjian summarizes some of Nichanian’s claims.

It [‘genocide’] is not simply a word we use to represent an event we can know. Rather it has become a word that represents us in our use of it. It does so by continually restaging what [Zabel] Essayan and [Hagop] Oshagan figure as the Catastrophe itself: not only the loss of the law of mourning, but also the denial of the loss of the law or mourning. ‘Genocide’ denies this loss and so performs the Catastrophe again and again.[37]

He continues, stating that ‘…”Genocide” is not itself a silence; rather it imposes a silence by entombing the Event [Armenian Catastrophe/genocide] within the pursuit of a calculable verdict.’ In this linguistic configuration of ‘genocide’ Kazanjian and Nichanian are concerned about the un-transmittable experience of mass death on such a large scale that it remains indescribable despite linguistic attempt to do so. Furthermore, this passage suggests that naming anything a ‘genocide’ renders its indescribability mute and thus perpetrates the horror of events like state sponsored mass death in trying to rationalize or calculate the incalculable. The loss of concern here appears to be the loss that occurs when trying to translate complex and unknowable histories and experiences into language.

Despite these claims to the contrary, how might the word ‘genocide’ also act as a generative naming and performative framing of a catastrphoic event like the AIDS crisis whose complex history has been, as Finkelstein noted, largely ‘slipped under the shadows of our [current] zeitgeists, and well-worn media tropes supplant more disorderly truths?’[38] How might employing a highly contested term like ‘genocide’ to describe the AIDS epidemic by artist and activists in the 1980s and 1990s perform an opening up of political power for queer subjects that were considered disposable, undesirable and un-grievable? Additionally what political and affective implications might there be to name and remember the AIDS crisis in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s as a form of queer genocide?

Teaching AIDS as Genocide

During my experience volunteering at a queer and trans youth drop-in center in central Maine over the last decade, an insatiable amount of energy, resources and time has been squandered on fights to repeal Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and gain access to same-sex marriage benefits. During this same time AIDS service organizations were handed the largest austerity measures in the history of the epidemic, marked locally by the closure of the Maine AIDS Alliance, All About Prevention, the Lewiston/Auburn needle exchange, and the Maine Community Planning Group on HIV Prevention of which I was a member. Numerous services for young queer and trans folks were also closing their doors concurrently.[39] Many of the queer and trans young people who came to the drop-in program were devastated in 2009 when the gay marriage referendum failed in Maine only to be overjoyed by its approval by referendum in 2012. The emotional habitus now seemed much like Yasmin Nair and I had previously described in the Spring 2011 edition of the online journal We Who Feel Differently,

Years from now, children will draw around campfires and listen to tales of the dark ages when gay marriages were not allowed. Their eyes will widen at this historical fiction: first, gay men and lesbians were repressed; then, they gained a measure of sexual freedom in the 1970s; were struck by AIDS in the 1980s (as punishment for their pleasure-seeking ways); and finally came to realize that gay marriage would be their salvation.[40]

Kenyon Farrow, the former director of Queers for Economic Justice, shares a similar sentiment. Speaking on a December 2012 a panel about gay marriage and equality at the New School for Social Policy in New York City, Farrow stated:

One of the things that I think we need to be very careful [about] is how the push for same sex marriage is not a natural, it’s not… I want to remove this assumption that this [gay marriage] is next step in kind of LGBT… We went from Stonewall and now marriage is what made logical sense. No. That was actually a process that was very much involved in a kind of response to AIDS and a kind of reaction to ACT UP and to some of the more radical elements in queer organizing. And some political choices were made to drive us in this particular direction and that there are a hell of a lot of resources that have also backed up that decision.[41]

It appears the emotional habitus in which queer political work is now done has once again significantly shifted, where anger and an accompanying radical political vision has been traded in for respectable calm and political inclusion within the status quo. For example, queers have somehow gone from demanding universal health care during the AIDS crisis, to demanding marriage rights so they can access health insurance through partner benefits, assuming one has a job with health insurance benefits in the first place.

Any attempt to unpack which numerous events have structured the shift in emotional habitus is beyond the scope of this essay, however, it’s important to note that the structuring function of neoliberal economics alone is not a sufficient optic to account for these changes. It is clear that an epochal shift in political disposition amongst LGBT people has occurred between the years of cultural production documented in this essay. Present-day gay and lesbian politics and visual representations have largely distanced themselves from sexual liberation and HIV/AIDS histories in an attempt to appear respectable and deserving of the tenuous rights gained thus far. Worse yet, are present-day gay and lesbian political organizations and accompanying visual narratives that prey upon and co-opt such radical political movements with deeply revisionist agendas. Suddenly the Stonewall riots become a quaint tea party paving the way to nuptial bliss and the AIDS crisis becomes a moment of great maturity for gay men who have now left behind their rebellious, promiscuous, youthful bad boy days at the kids table and now occupy a proper place at the table amongst the rest of the real adults. So the question remains: how did such a radical shift in mood or collective affective states, which shapes what is imagined as possible, take place and how do we revive a radical queer political imagination in the present?

Remembering the Dead

In Vito Russo’s speech Why We Fight, delivered at an ACT UP demonstration at the Department of Health and Human Services in Washington D.C. on 10 October 1988, just two years before he died from AIDS related illness, he said,

Living with AIDS is like living through a war which is happening only for those people who happen to be in the trenches. Every time a shell explodes, you look around and you discover that you’ve lost more of your friends, but nobody else notices. It isn’t happening to them. They’re walking the streets as though we weren’t living through some sort of nightmare. And only you can hear the screams of the people who are dying and their cries for help. No one else seems to be noticing.[42]

Now that most of the trenches that have been filled with the lifeless bodies of quickly forgotten HIV-positive queers are quietly covered over, what does it mean not to historicize this period of the AIDS crisis in the same manner as those who experienced it first hand and so loudly named it genocide? What does it mean to misremember or forget the war dead who fought courageously so that fags like me could live? Those same queers, who like Michael Callen and Richard Burkowitz, helped develop some of the first strategies on how to have sex in an epidemic without becoming another casualty in the ongoing war against queers.[43]

Again, to return to the question this paper opens with: what does it mean to not remember the AIDS crisis on the terms by which it was described by those queer artists and activists who experienced the death and destruction first hand, but are no longer here to tell us about it? And what do we make of those who survived and continue to produce AIDS histories through art and visual culture while abandoning the terms by which their experience was once so readily described?

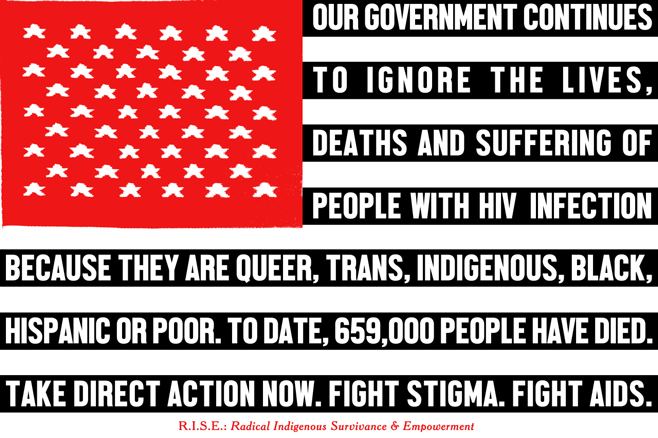

Demian DinéYazhi’/R.I.S.E.: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment, American NDN AIDS Flag, 2015, 11 x 17 inch poster. Image courtesy of the artist.

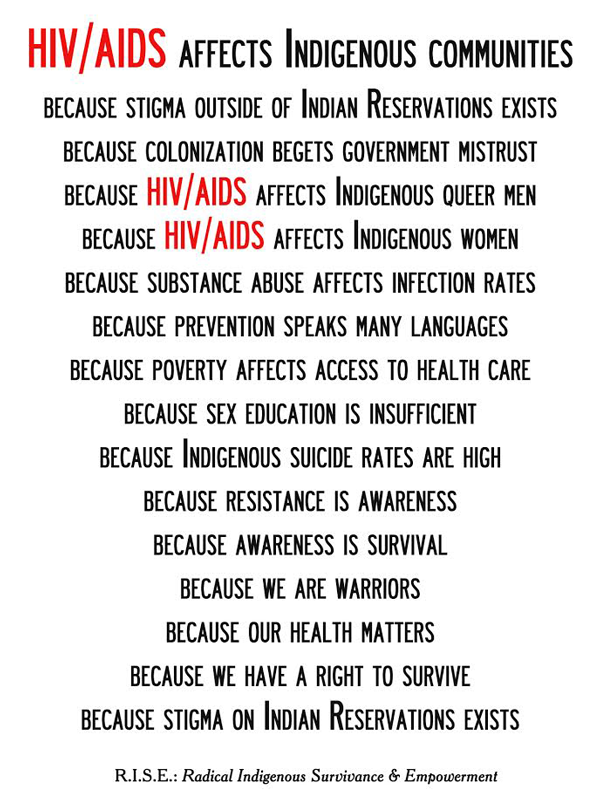

And what might reasserting the genocide framework on the queer historical experience of HIV/AIDS do? Could a present-day naming of the past queer collective experience of HIV/AIDS be as generative as I perceive it to have been historically? Might queers that are not already part of other marginalized communities then see themselves in stronger relation to other peoples struggling against settler colonialism, racism and xenophobia concomitant with genocides? How might an acknowledged history of queer genocide temper queer demands for recognition and inclusion within state forms that have and can be used to dehumanize us once again? For the moment, the answers to these questions remain entirely speculative, but the reassertion of the AIDS crisis as genocide has begun creeping back into contemporary queer work created by a younger generation of cultural workers. For example, Eric Stanley and Chris Vargas’ featurette Homotopia (2007) or my own experimental short film things are different now… (2012) or the transdisciplinary work of queer indigenous artists like Demian DinéYazhi’ that put AIDS in direct dialog with histories of genocidal settler colonialism. These works, if nothing else, open up a space to imagine what remembering our queer histories differently might mean.

Demian DinéYazhi’/R.I.S.E.: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment, HIV/AIDS Affects Indigenous Communities, 2014, 11 x 17 inch poster. Image courtesy of the artist.

[1] Finkelstein, Avram. ‘AIDS 2.0.’ Artwrit. (Accessed January 20, 2013). http://www.artwrit.com/article/aids-2-0/.

[2] For examples of observations similar to Finkelstein’s see Feiss, E.C. ‘Get to Work: ACT UP For Everyone.’ Little Joe, November 2015, 158-71; Juhasz, Alexandra. ‘Acts of Signification-Survival.’ Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 55, 2012; Kerr, Ted. ‘Time Is Not A Line: Conversations, Essays, and Images About HIV/AIDS Now.’ We Who Feel Differently, 3, 2014. http://wewhofeeldifferently.info/journal.php?issue=3#TOP; Nishant, Shahani. ‘How to Survive the Whitewashing of AIDS: Global Pasts, Transnational Futures.’ QED: A Journal of GLBTQ Worldmaking 3, 1, 2016, 1-33.

[4] Treichler, Paula A. ‘AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification.’ AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism (Boston: MIT Press, 1988), 34.

[6] http://www.actupny.org/diva/CBnecessary.html.

[7] Masson, Kiki. ‘Manifesto Desitny.’ Poz Magazine (New York City), 1996. (Accessed July 17, 2016.) http://www.poz.com/articles/252_6966.shtml.

[8] Juhasz, Alexandra. AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 70-73.

[9] Wentzy, James. ‘Interview with James Wentzy.’ Interview by Ryan Conrad. Spring 2011.

[10] For brief description of the links between AIDS Activist Video and technology, see Lucas Hilderbrand, Retoractivism. Also see AIDS Activist Video archive, New York Public Library.

[11] For a history of the closures of commercial gay sex venues in New York City see: Colter, Ephen Glenn. Policing Public Sex: Queer Politics and the Future of AIDS Activism. (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1996); Delany, Samuel R. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. (New York: New York University Press, 1999); Warner, Michael. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life. (New York: Free Press, 1999).

[12] By Any Means Neccessary. Directed by James Wentzy. New York City, 1994. (Accessed January 20, 2013). http://www.actupny.org/diva/CBnecessary.html.

[15] Crimp, Douglas, and Adam Rolston. AIDS Demo Graphics. (Seattle: Bay Press, 1990); Finklestein, Avram. ‘AIDS 2.0.’ Artwrit. (Accessed January 20, 2013.) http://www.artwrit.com/article/aids-2-0/.

[17] General Idea: Art, AIDS, and the Fin De Siècle. Directed by Annette Mangaard. (Toronto: Vtape, 2008.) DVD.

[18] Bordowitz, Gregg. General Idea: Imagevirus (London: Afterall Books, 2010).

[19] Bordowitz, Gregg. The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous and Other Writings, 1986-2003 (Cambridge: MIT, 2006.), 13.

[20] Hubbard, Jim. A Report on the Archiving of Film and Video Work by Makers with AIDS. Report. (Accessed January 20, 2013.) http://www.actupny.org/diva/Archive.html; Bordowitz, Gregg. The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous and Other Writings, 1986-2003 (Cambridge: MIT, 2006).

[21] Santos, Nelson. NOT OVER: 25 years of Visual AIDS (New York: Visual AIDS, 2013).

[22] Atkins, Robert. ‘Off the Wall: AIDS and Public Art.’ RobertAtkins.net. (Accessed July 17, 2016). http://www.robertatkins.net/beta/shift/culture/body/off.html.

[23] Siegel, Robert (writer). ‘Acting Up on the Evening News.’ Transcript. In All Things Considered. National Public Radio. June 15, 2001. http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2001/jun/010615.actingup.html.

[24] Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald. ‘ACT UP Protesters Reflect on AIDS Demonstrations 25 Years Ago.’ San Francisco Examiner, June 10, 2015. http://archives.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/act-up-protesters-reflect-on-aids-demonstrations-25-years-ago/Content?oid=2932874.

[25] Rich, Frank. ‘Making History Repeat, Even Against Its Will.’ Review of A Bright Room Called Day. The New York Times, January 8, 1991. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/08/theater/review-theater-making-history-repeat-even-against-its-will.html.

[27] King, Dennis. ‘America’s Hitler? Behind the California AIDS Initiative.’ New York Native, November 3, 1986.

[28] Tighe, Elizabeth et al. ‘American Jewish Population Estimates: 2012’. Brandeis University: Steinhardt Social Research Institute, 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

[29] Hallas, Roger. Reframing Bodies: AIDS, Bearing Witness, and the Queer Moving Image (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 38.

[30] Downs, Jim. ‘The Body Politic.’ Stand by Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation (New York City: Basic Books, 2016), 113-41.

[31] For an elaboration on this concept and the arguments over the use of Holocaust analogies see: Shaw, Martin. ‘The Holocaust Standard.’ What Is Genocide?, 2nd Edition (New York City: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 53-65.

[32] Gould, Deborah B. Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 165.

[34] Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009), XIX.

[35] Stein as Quoted in Gould, Deborah B. Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 166.

[36] Here I am thinking of another set of videos put together by James Wentzy documenting the many political funerals ACT UP did including those of David Wojnarowicz, Tim Bailey and ACT UP’s Ashes Action.

[37] Kazanjian, David, and Marc Nichanian. ‘Between Genocide and Catastrophe.’ In Loss: The Politics of Mourning (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 125-47.

[39] Conrad, Ryan. ‘Against Equality in Maine and Everywhere.’ In Against Equality: Queer Critiques of Gay Marriage (Lewiston: AE Press, 2010), 43-50.

[40] Conrad, Ryan, and Yasmin Nair. ‘Against Equality: Defying Inclusion, Demanding Transformation in the U.S. Gay Political Landscape.’ We Who Feel Differently, 1, 2011. (Accessed January 20, 2013). http://www.wewhofeeldifferently.info/journal.php?issue=1#AE.

[41] Marriage and Equality with Melissa Harris-Perry at the New School for Social Policy. Youtube. Accessed January 20, 2013. http://youtu.be/BnFR4kpDYUE.

[42] Russo, Vitto. ‘Why We Fight.’ Speech. Accessed January 20, 2013. http://www.actupny.org/documents/whfight.html.

[43] Callen, Michael. ‘How to Have Sex.’ Purple Heart. 1988, CD.

Ryan Conrad is a PhD candidate in the Interdisciplinary Humanities PhD offered through the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University, where he is also a part-time faculty member in the Interdisciplinary Sexuality Studies and Film Studies programs. Conrad is also the co-founder of Against Equality (againstequaltiy.org), a digital archive and publishing collective based in the United States and Canada. His work is archived at faggotz.org.