Caleb Lightfoot and J. Eric Simpson

Project Statement: Terroir (French pronunciation: [tɛʁwaʁ] from terre, “land”) is understood as the unique set of environmental factors – climate, soil type, geomorphology, and living organisms (animal, plant, microbes, etc) that affect a crop’s phenotype. Terroir is a specified character, a feeling, taste, smell, etc, that is made by the unique combination of these factors. Terroir is an emergent whole, irreducible to any of its parts, and made by the interconnectedness of its constituent systems.

Lightfoot and Simpson use “terroir” as a methodology to think through the complex ecology of monoculture crop production: an ecology that exists as the interweaving of many complex operations. Their installation, Terroir, is made up of individual projects that explore the unique set of historical, political, spatial, and technological factors that govern this global agricultural system.

Media: IBC chemical totes, greenhouse grow lights, recycled dirt from Bayer Crop Science greenhouse (Lubbock TX 2018), synthetic fertilizer injector pump, high pressure braided hose, water, blue turf dye, Monsanto’s Delta Pine DP1830B2XF™ & DP1612B2XF™ transgenic cottonseed pigment on 100% cotton paper, careless weed seed on locally sourced handmade cotton paper with planting trays and heat mats, Bayer’s transgenic cotton seed, 2.5 gallon Liberty Link herbicide jugs, TV monitor with celluloid film, greenhouse plastic, video, artist books: screen print on 1980’s cotton seed bag, inkjet prints on paper, and vellum.

J. Eric Simpson Statement:

Botanical illustrations of the early modern period (1550-1800), the “big science” of their day, served as documentation of useful plants found in colonial territories such as the Americas, Africa and the East Indies. Plants such as tobacco, sugar cane, cinnamon, and tea were but a few items deemed reliable “cash crops.” Illustrations led the way to commodities that created the first global trade networks. Profit and power justified and rationalized the harsh realities of colonialism by the western world. (Schieber, Swan)

My taxonomic paintings and drawings draw parallels between the profitability of colonial botany with that of today’s ever expanding and merging agro-chemical corporations (Bayer, Monsanto, BASF, DOW, DuPont, and Syngenta – “the Big 6”)[1]. Through the production of transgenic seeds[2] and pesticides[3], these industries act as the ever-present hands guiding the monoculture system around the globe. As of 2015 the four largest of these seed/chemical firms collectively controlled 76% of soybean seed, 82% of corn seed, and 91% of cotton seed production globally. (Howard and Maisashvili et. all)

Using transgenic cotton seeds and chemical herbicides as paint medium throughout my practice, I point to a co-evolutionary dialogue between the development of transgenic cotton and the evolution of herbicide resistance (HR) in weeds of the South Plains. This co-evolution complicates the traditional narrative of agro-chemical / bio-tech that places corn, soy, and cotton as the “cash crops” of the monoculture system. My research suggests, instead, that a new and significant “cash crop” for these multi-national companies is in fact the ever-evolving weed. As herbicide resistant weeds evolve, new herbicides and seeds are engineered and produced at ever increasing prices. This creates an endless loop of compounding market power and product security at the expense of the farmer, the land, and the environment.

Caleb Lightfoot Statement:

‘… the God who still hid in the worldview of an ecology that was self-correcting, self-balancing and self-healing—is dead … The human is no longer that figure in the foreground which pursues its self-interest against the background of a wholistic, organicist cycle that the human might perturb but with which it can remain in balance and harmony, in the end, by simply withdrawing from certain excesses.’

-Mckenzie Wark, Molecular Red

‘The doors! The doors! In wisdom, let us be attentive!’

-From the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom

In its most basic form, the etymology of the word liturgy means ‘the work of the people.’ For the Orthodox and Catholic, the ‘right-believing’ and the ‘universal’, this collective work performed among gathered believers replicates a cosmic order on a localized scale. The multitudes gather together about the center of the One, and the vaults of the cathedrals construct anew the sealed and insulating dome of the heavens that emanate outward in varying degrees of glory.

The Holocene, an epoch of earth’s history that began nearly 12,000 years ago and has continued up until the present time, has given way to the Anthropocene: the era of geological time defined by large scale human intervention. Here, the ‘work of the people’ literally has global (and globalizing) implications, at a scale not previously fathomed by the liturgists of the Holocene. Nietzsche wondered, in the late twentieth century, who scrubbed away the sky in the wake of god’s death: Copernicus first, and carbon emissions second. The sky has quite literally been punctured, and the complexity of the ecological situation of our present era demands that designers forsake a nostalgia for the One, embracing the complexity of the multiple. The vaults of the sky must be redesigned.

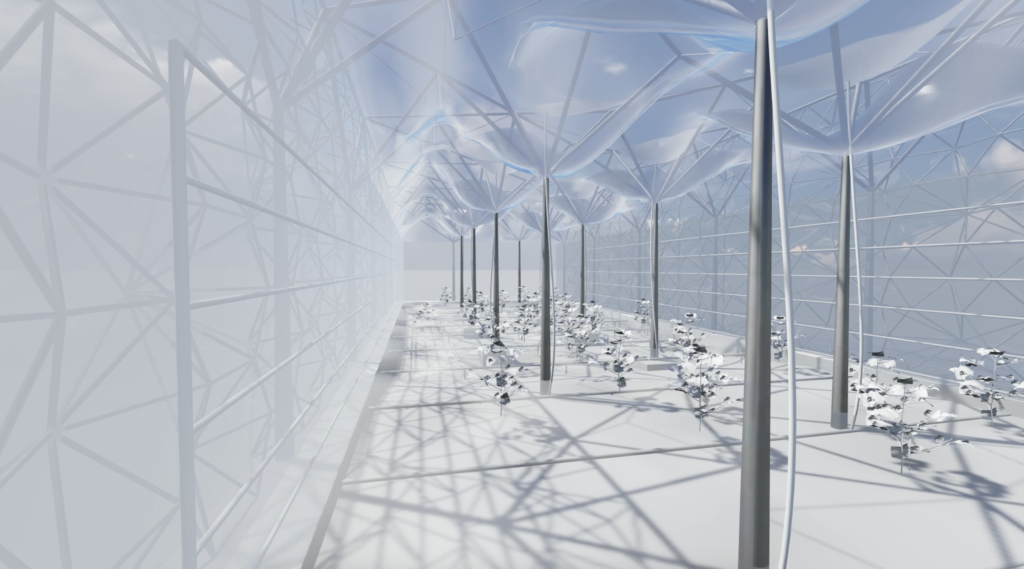

This work seeks to address this problem. Peter Sloterdijk points out that the Greenhouse is the ultimate project of modernity: a totalizing interior that functions as a private and acclimatized world (Sloterdijk, 2005). This work seeks to rethink the greenhouse: not as world-extending apparatus of corporations and the monoculture industry, but as a collective act, a worlding that binds humans with plant life. It does not long for the failed world of the One and the self-regulating ecology it belonged to. The need for self-regulation must be deployed at a local scale.

The vaults of this cathedral are not filled with the gods of the Holocene, but with trapped heat and collected water: A new climate giving life to the post-human assemblage found within. Pores along the surface, like Stomata in plant anatomy, open and close to admit more or less outside air. This is a world for both the workers and non-human actors: a post-human liturgy for the Anthropocene.

All images courtesy the artists.

[1] As of September 1, 2017 Dow and DuPont completed a $130 billon dollar merger. As of June 7, 2018 Bayer purchased Monsanto for $66 billon dollars and was subsequently forced to sell off its cotton seed division to BASF – “the Big 6” become “the Big 4”.

[2] a transgenic seed is the byproduct of genetic engineering where a desired trait from one species can be bred into the DNA of another species. This form of breeding is unique in that it allows for cross-breeding between species that could not breed using traditional methods. Another term for this is Genetically Modified Organism (GMO).

[3] Herbicides (plants) and Insecticides (insects). Examples include: Roundup (glyphosate) Liberty (Glufosinate)

Eric Simpson is an artist, researcher and novice farmer in west Texas. His interests include monoculture crop production, bio-technology, weed science and water collecting. His exhibitions include: Lubbock City Eternal – 5&J Gallery, Lubbock TX (2018), Transition and Transform – James Gallery, Hamilton ON (2018), Incident Report No. 102 – Hudson NY (2017), Co-Modify – Indigo Gallery,Buffalo NY (2017), Amid/In WNY Epilogue – Hallwalls gallery, Buffalo NY (2017),and The Measure of All Things – The University at Buffalo (2016). He received his BFA at Texas Tech University in 2013 and an MFA from the University at Buffalo in 2017. He is currently an artist in residence at the Charles Adams Studio Project and is farming with his family in Shallowater Texas.

Caleb Lightfoot received a BA of Architecture from Texas Tech University in 2015 and MA of Architecture from Texas Tech university in 2017. Trained in the discipline of architecture, Lightfoot’s work exists at the intersection of several fields. Collaborating with artists, architects, and classical archaeologists, his work addresses themes of land use, the built environment, culture, anthropology, and speculative design. Critical modes of representation and processes of engagement with places is a core research question that connects all of his work, implementing traditional tools as well as 3D modeling and digital post-processing. He has participated in several interdisciplinary field programs including Land Arts of the American West and the American team of archaeologist at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace. He is also the coauthor of a book chapter entitled Describing Hermion/Ermioni. Between Pausanias and digital maps, a topology which will be included in a forthcoming anthology: “Re-mapping Archeology” (Routledge, 2019)