Deborah Margo

My practice is anchored in issues of identity across multiple geographies. I am an Ashkenazi Jew and first-generation Canadian, born in Montreal, living in Ottawa. My family comes from Russia, Poland, Germany, the UK, and now Canada. Today we remain scattered over the globe.

What I want to focus on in these pages is specific to place, the seasons and my practice as a maker of sculptures and installations. Two questions have been steadfast in the work I do: where do I belong? where does my work belong? Mutable answers have taken form since the 1980s, continuing to this day. The metaphors surrounding gardening and the making of gardens extend back to my English and German grandmothers, and to my mother who, at 88 years old, continues to garden on her windswept, shady balcony twenty-two stories above terra firma. My brother also owns and runs a landscaping company in Montreal. Tending to plants and making gardens are a multi-generational family tradition.

I started practicing as a visual artist in 1984. In 2004, I became a professional gardener in the Ottawa Valley. Today I continue to design, maintain, and consult for private clients. Gradually my knowledge and experience of tending to gardens has become a key part of my visual art practice as well.

Central to my practice, in all its forms, are materials and materiality. There is a dialogue between myself and what I have selected to work with. My will and preconceptions are constantly challenged; the notion that I have some form of power over it is constantly broken and my humility tested.

My gardening practice starts around April and continues into November. I consult, design, and maintain gardens. On average, each year I work for twenty-five to thirty clients. For some, I work in the spring and fall. Others I visit every week.

I work mostly on my own, but I do have former students of mine, from the University of Ottawa, help me when necessary. My favourite assistant, Jake Ireland, has recently completed a horticultural degree. His skills, knowledge and gardening aesthetic are invaluable.

As an example of the scope of work I undertake, I started working on Anne’s garden four years ago. It borders on a residential street and consists of about an acre of land. What she particularly wanted me to develop was her front garden and to remove the lawn. Anne wanted colour: bright pinks and oranges.

Overall, the site is very shady, but along the street there’s a band of sunlight, roughly a metre wide by 20 metres long. Punchy coloured annuals now grow there from May through October – zinnias, cosmos, sunflowers – attracting bees and comments from the area’s residents. I harvest the seeds every season and have more than enough for the next year, as well as to give to other clients.

View of Anne’s garden, 2023. Image courtesy of Deborah Margo.

I make gardens where I try to meet what the client wants, what they are interested in. I see each garden as a self-portrait of the owner. I find they often like some plants while fervently disliking others; favourite bloom colours are always a good place to start a conversation. The range of plantings I tend include vegetable gardens, as well as perennial and annual gardens.

I frequently move plants between the different gardens I look after each year. Transplants and seed harvests are moved around the city or are given away to other gardeners I know. My gardening zone (5b) and climate change are also active ingredients. I have learned mostly by doing, talking to other gardeners, and by research.

As mentioned, I started my gardening business in 2004; it was also the year I made my first installation using plants, at Axe Néo-7 in Gatineau, Quebec, an artist-run gallery. It was a project I was invited to be part of, initiated and curated by Stéphane Bertrand, a landscape architect. Over a three-year period, he invited landscape architects and visual artists to make different kinds of gardens, inside and outside the gallery spaces. My installation, La détente, started in April and continued through November, teaching me a great deal about the time necessary for such projects.

I was then living in Ottawa’s Little Italy neighbourhood where there were many gardens on small private sites. A lot of produce was grown each season and shared. When I first moved to the area, one of my neighbours, Adele, gave me scarlet runner beans – a fast growing, strong vine with beautiful deep-orange blooms. For La détente, I germinated multiple scarlet runner bean vines at home, then brought them to the gallery where they were eventually planted outside when the risk of frost had passed.

As the plants were growing inside, I collected trellis materials on city collection garbage days. Everything from hockey sticks to mops, branches, baseball bats were gathered, to help build supporting structures for the scarlet runner vines. My hope was to grow the vines over the course of the summer to reach the top of the structures by August.

The site was immediately behind Axe Néo-7’s galleries and I soon discovered the soil was very poor. When I started digging to plant, I came upon pieces of metal, bricks, and gravel – to grow anything at all was a challenge. Nevertheless, once the structures were built and installed outside, the runner beans were planted and tended throughout the growing season.

La détente, scarlet runner beans, found trellis materials, Axe Néo-7, Gatineau, Quebec, 2004. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

Because it was an open public area, the biggest concern was acts of vandalism, but, to my surprise, I found the surrounding community respectful of the installation. Individuals of all ages would often come to help me water or weed, giving their advice on how the vines should be grown and cared for. The formerly inhospitable site became a garden for people to meet, work, talk and exchange.

I was successful in growing the scarlet runner beans to their full height and, in late fall, harvested a good crop of beans. Once packaged, they were given away to people who came to the gallery, accompanied by instructions on how to grow them. I made their packaging from recycled cereal box liners, stitched together with thread, holding the beans inside.

Other beans were distributed across the country in my friend Cindy Deachman’s magazine, Toast. We manually inserted them into its centrefold before they were mailed out. The beans made it to different places across the country where they could be planted, once again accompanied by instructions on how to grow them.

Another project involving plants, was at Ottawa’s Experimental Farm which is run by the Canadian government’s Department of Agriculture. There were six artists invited to make gardens, by curators Mary Faught and Judith Parker. I chose to grow more than twenty kinds of squash on two sites at the farm, wanting to draw attention to the many varieties and unusual forms existing in the cucurbita family. At one site, I built a series of wood structures. At the second location, I constructed a tunnel-like structure using horse fencing with vertical rebar pole supports, where the different squash vines grew vertically, with the squash hanging down as they grew to maturity.

Again, I was prepared for my work to be vandalized or damaged by a community of groundhogs, however, because the area was frequented by dog walkers, both sites grew very well. The dog walking visitors inadvertently became the custodians of this project. As with my work at La détente at Axe Néo-7, they would often talk to me about how things were growing, their opinions about the project, or asking me questions about what I was doing.

In September, I harvested more than 150 squash. Once they were all collected, I invited local chefs I knew to cook squash soup, following recipes of their choice. The range of squash soups were diverse: one soup was an invented recipe; another was Thai based; one included barbecued squash with a vegetable broth. All soups were served on the final day of the exhibition in late September, along with donated bread from a local bakery. Over 250 people attended. It was a wonderful way to celebrate both the end of the growing season, as well as the end of the project.

From Seed to Soup – Meet the Cucurbita Family, squash plants and wood structures, Experimental Farm, Ottawa, 2014. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

From Seed to Soup – Meet the Cucurbita Family, squash harvest, 2014. Image courtesy of Deborah Margo.

Spectral Weavers – Collaborative Installation Gardens

I have also been collaborating on plant-based installation projects with multimedia artist, Annette Hegel, since 2015. We call our duo Spectral Weavers. We share similar interests in growing gardens and plant life. However, my expertise comes more from working with materials three-dimensionally, whereas she is very knowledgeable in terms of the media arts. This has allowed us to both develop our work in new directions, using a range of materials along with digital imagery, sound recordings, and light components in projects both inside and outside.

Our first project, Asphalt Oasis, was in the schoolyard of the building, De Mazenod School, where our studios are still located, as the school was not in use during the summer then. Our goal was to sow a garden in the cracks of the asphalt. To plant the seed in the ground, we often had to use a chisel to loosen up the earth and to insert the seeds. It was not easy!

There were squirrels, chipmunks and, what we later discovered, skunks eating the different seeds, but we still managed to make a large garden installation including different varieties of sunflowers, multiple colours of fast growing morning glory vines, deep crimson amaranth, and well established so-called weeds, such as Manitoba weeds. Some of the plants grew in the cracks, some of them in containers, including repurposed rice bags. We had vertical strings running through the schoolyard with the morning glory vines running up them, helping to further transform this previously desolate space. It was open to the public at Ottawa’s Nuit Blanche event, on a stormy September evening, and included projections of the photographs we had taken of the garden throughout the four months we had worked on it.

Other projects we have worked on collaboratively have focused on tracking bumblebee culture, including how climate change and loss of natural habitats are threatening their existence. For the Ottawa City Hall Gallery, our installation, By the Bee, included a landscape of sedum plant carpets accompanied by grow lights, as well as beeswax pod-like sculptures based on the tiny nectar pods that bumblebees build, live in, and collect their nectar.

It was an immersive exhibition where all the senses were involved to draw attention to the flight and song trajectories of bumblebees. The multi-coloured and textures of multiple sedum carpets came from a farm in central Ontario, where they are usually destined for rooves. At the gallery, we draped them over wooden structures we built on location. We also included recorded bumblebee songs we had made in a field in nearby Perth, Ontario. Other elements included a digitized light system on a timer allowing it to come on at daybreak, dim at dusk, then darken, depending on what time of the day it was. Smell was also invoked: the pod sculptures contained small lights; when the beeswax became warm, it let off a subtle honey-like perfume.

Annette Hegel and Deborah Margo, By the Bee, sedum carpets, wood structures, beeswax sculptures, grow lights, arduinos, sound recordings,Ottawa City Hall Gallery, Ottawa, 2019. Image courtesy of Annette Hegel and Deborah Margo.

Symbiosis – Miniature Gardens

Since 2021, I have been working with different kinds of moss I have collected from an abandoned lot near my home. Formerly there was a gas station there, so the ground is quite toxic, yet the moss survives. Mosses have no root systems and adapt to different climates. Rather than die, if they do not have adequate moisture they rest or go dormant. They will return to health if given the right growing situation.

Initially I grew my moss collection on limestone boulders in my studio. I set up lights, as well as watering and humidification systems, in a small temporary greenhouse, because I was doing my research in the winter, when the ground in Ottawa was frozen and covered by snow. By springtime it became clear my carefully designed growing system had failed – the moss was either drying out or going moldy.

Eventually, I discovered it grew better next to my window, wrapped in plastic sheeting, with occasional misting. Instead of using the boulders I had brought to my studio as growing supports, I used containers, such a plastic food tray I took from the garbage, then wrapping them carefully to contain both the plant material and the moisture. Tiny systems of growth started to return quickly which continue today. Accompanying these miniature gardens, I am also developing a series of paper works based on the photographic documentation I have been gathering of the mosses’ slow growth.

Symbiosis, moss, ferns, gravel, plastic food tray, 2023. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

Imagined Gardens as Knitted Journals

Though this may seem like an unlikely thread, knitting also connects my gardening and art practice. It has become part of the bridge between these two parts of my creative life.

Like gardening, my mother taught me to knit when I was a child, a skill she has now passed onto my daughter. In 2009, knitting’s role changed for me when two of my gardening clients gave me different challenges. Margaret, an avid knitter, told me about the miracle of turning a heel when making socks, and convinced me to give it a try. Soon after, Jean asked if I would like to have bags of wool and boxes of knitting books from her deceased father’s stash and library. He had been a medical doctor who had an intensive knitting practice in his free time. The depth of colour, material and resources had me reassess knitting’s role in my life as a pleasurable past-time. I started thinking of stitch-making as a form of painting that could exist in three-dimensions.

A reassessment of colour and questioning of form was the basis of a new project in 2010, when I was traveling for four months in Europe with my family. The rules of the established knitting game were straightforward: I would purchase yarn in different places that would reflect the locale of where we were. We visited 21 different places, I collected wool and knitted as we travelled. For example, drawings were made of Prague’s walkways with their stone tile patterns, later translated into complex multi-yarn motifs. The Alhambra’s history of tile design and pattern was also a revelatory experience. I was able to knit anywhere, taking my work out of a knapsack, sitting down while waiting for a bus, subway, or a boat, wherever we might be. It was also a conduit for connection with others as it was an easy way to start conversations with people I met while travelling.

I came back to Canada and continued working with drawings, photographs, and the yarns I had collected. In 2013 I showed for the first time a series of scroll-like sculptures at Patrick Mikhail Gallery, then in Ottawa, that were stretched and pulled in different directions traveling through the gallery’s spaces. Each work was supported by a wooden spindle I had turned in Ottawa, made from local woods such as maple and pine.

Topographies, textiles and turned wood, 2013, Patrick Mikhail Gallery, Ottawa. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

First dye kitchen at Alchemy residency, Hillier, Prince Edward County, Ontario, 2017. Image courtesy of Deborah Margo.

Making Colour from Plants

Reading Harvesting Color, by Rebecca Burgess, introduced me to fiber sheds and natural dyes in 2016. Her book was timely, helping me to consider how colour, textiles, sculpture, installation, as well as the growing of plants, could all be part of my practice as a visual artist and gardener. The problem with the book was many of the plants did not have anything to do with my region or its short growing season, as she focused on the southwest of the United States which is much warmer than where I live. Although Burgess’s ideas were helpful in getting me started, it was also frustrating. Inadvertently I became a student again. I knew how to grow plants in my hardiness zone, but not how to make and use them for plant dying.

The learning path I followed was varied, including reading books, on-line postings, and sites, taking workshops, trying to find individuals in the Ottawa Valley who had a dye practice using plants and had an interest in growing and harvesting them as well. It also took me to different urban and rural places such as the Contemporary Textile Center in Toronto, as well as a farm in Gatineau, Quebec. The information I gathered was contradictory; myths and approaches to applied chemistry collided.

Subsequent books that helped me were recommended by my friend Carl Stewart who is a wonderful Canadian dyer, weaver, visual artist, and teacher. His suggestion of Wild Colour, by Jenny Dean, gave me the confidence to start dying using plants I could gather and grow locally, as well as extract their dye colours.

Jason Logan’s Make Ink was inspirational. Logan is a forager and ink maker, living in Toronto. He is also an illustrator and writer, publishing a wonderful weekly newsletter, containing poetry and storytelling, as part of his ink making adventures. He believes ink can be made from of anything – a cigarette butt can be as amazing as wild grapes. He is an experimenter and investigator extraordinaire. Recently his film, The Colour of Ink, was released, which I recommend seeing.

My dye practice began in 2017, when I attended a residency, Alchemy, in Hillier, Prince Edward County, Ontario which combined food and art. I met wonderful people and had uninterrupted time to focus on foraging and dyeing. I started cooking a wide range of local plant matter to see what colours I could extract. Fugitive and permanent dyes were made and tested on different fabrics I had brought with me.

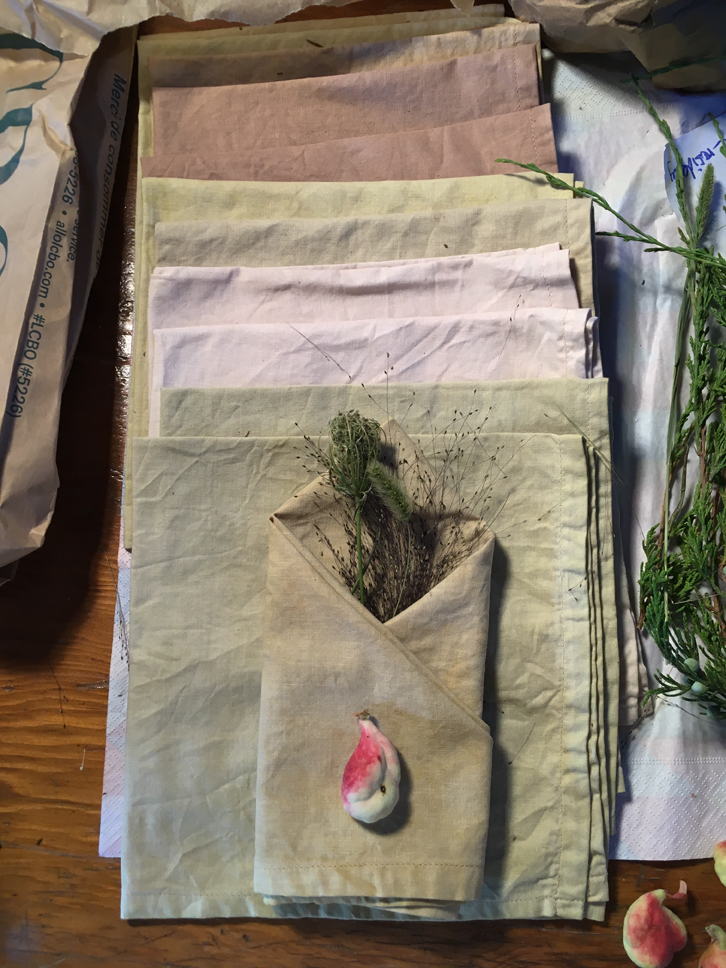

At Alchemy, one of my projects was to sew a series of table napkins out of cotton. Because we were preparing and eating many of our meals together, as well as talking about practices of food preparation, this offering made sense to me as a small gesture to all the participants. The cotton squares were dyed with plants I had gathered nearby and experimented with throughout the residency. They included sumac and juniper berries foraged along the nearby former train tracks where I walked and cycled. Folded to contain some of the gathered plants, they were given on the last night of the residency at the final supper we had together. Next to the dining room table I placed a selection of the dyes I had made, along with my assembled dye book containing my research of notes and dyed textile samples.

15 squares, cotton and foraged plant matter, 2017. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

A second dye plant project was started with a potted dye garden I planted outside, as part of a commission awarded by the Ottawa Art Gallery, celebrating the opening of its new building in 2018. I purchased a cubic yard of earth and filled the pots I had, germinating an assortment of annuals with strong dye qualities, such as zinnias, marigolds, and dyer’s coreopsis. I also set up my first dye kitchen at my studio, experimenting with the dyes I made from my gathered plant material. I continued to learn about fugitive and permanent colour as well as the role of daylight and time in changing colour.

The final work was an indoor and outdoor site-responsive installation located in one of the gallery’s staircases, entitled From Here to There – Making Colour. Fabrics included linen, different silks, and cottons, all dyed a range of colours exploring the warmer tones of yellows, pinks, browns. The fabrics were loosely sewn together, with small earth magnets holding them on airplane cables that were stretched throughout the space. Some of the fabric elements were high above viewers, others at eye level. Some hung at the window wall, bordering onto the outdoor terrace where many of the dye plants I had originally grown in my dye garden were now planted in pots.

Dye garden for Ottawa Art Gallery commission, Ottawa, 2018. Image courtesy of Deborah Margo.

From Here to There – Making Colour, textiles, airplane cable, magnets, 2018, Ottawa Art Gallery. Image by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

Today

Three years ago, I moved. I now live near downtown Ottawa, next to the Rideau River. I started a new dye garden and now look after two allotment plots at nearby community gardens. It is a short walk to meadow landscapes adjoining bike and walking paths where I forage plant matter in the fall, such as staghorn sumac and goldenrod which both grow plentifully. I have also been one of the volunteers who helped establish a dye garden in 2022, under the auspices of the Mississippi Valley Textile Museum (Almonte, Ontario), due to the vision and perseverance of educator and visual artist Melanie Girdwood-Brunton. Together we have led dye workshops using harvested plants from the dye garden.

Because so much of what I have learned about plant dyes was done on my own, I discovered I had some major gaps in my education, including accurate methods for scouring and mordanting a range of textiles. Many of my questions have now been answered by intensive online workshops given by Mel Sweetman of Mamie’s Schoolhouse, located in Cape Breton, eastern Canada. I worked with her because I was looking for someone with a strong applied chemistry background who could explain the science behind the different dyes and procedures. Over the months of courses, I made hundreds of samples from blues to yellows, purples, blacks, and reds, using weld, madder and indigo plants. I am not satisfied by my green tones yet and plan to continue to improve my dyeing abilities this winter.

I have been pleased to use my recent dye education in the making of different works this past year. These pieces are often intimate in scale, multi-coloured, using plant dyes on cotton, linen and silk textiles, handmade papers, and wool yarns. I also often use wool from local mills combined with different fibres from my wool stash. Recently my knitted works have taken the form of gifts for the family of friends I have made.

A favourite project was knitting a sweater for my beloved friend of more than thirty years, Barbara. Following what has become a frequent process for me, she chose the pattern and colours, not unlike working with a client on what they want their garden to be. Last fall, I dyed many of the yarn colours to match the colour palette she had selected and gave her the finished sweater this past June. It fitted her exactly the way she wished.

|  |

(Left) Barbara’s sweater, plant dyed wool, 2023. (Right) Knitting Noah’s scarf, plant dyed wool, 2023. Images by and courtesy of Deborah Margo.

I now know that my sense of belonging is provisional and not based in being in one place. Similarly, after more than forty years of working as a visual artist, my communities are not based on a specific geography, but with people I have met who share ways of working across disciplines. My work stems from the belief that art making is a form of resistance in a broken world. Searching for beauty is necessary and possible to find in fragments of the garden of Eden.

I consider the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, of taking various forms of action intended to repair and improve the world. The outcomes of my investigations are projects that exist in multiple places, different kinds of institutions – art focused and not; inside and outside. Literal and metaphorical rootedness takes me to shifting sites, encountering the earth for growing and tending plants, along with the riches of their harvests. My actions allow for moments of belonging within the certainty of constant change.

This essay is based on a talk I gave in February 2023 for Growing Colour Together, WOVEN, Kirklees, U.K.

Born in Montreal, Deborah Margo lives in Ottawa, Canada. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Concordia University (Montreal) and a Master of Fine Arts from Temple University/Tyler School of Art (Philadelphia). She has also studied at the Haystack School of Crafts (Deer Isle, Maine, U.S.A.) and the Banff Centre (Banff, Alberta). She is an adjunct professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Ottawa, teaching at the undergraduate and graduate levels. During the spring and summer months she also works as a gardener.