Avantika Bawa

Avantika Bawa: How did you get interested in ruins?

Heidi Schwegler: In life, I’m compelled by the ruin. In the studio, I’m compelled to ruin things.

In 2009, after eleven years spent teaching fulltime in Portland, Oregon, I realized that something drastic needed to happen. I was craving change so profoundly that at times it felt like a personal apocalypse. My studio was feeling claustrophobic, my connection to the work was dead and my community felt limited. I had a strong desire for expansion—to step out of the vacuum and engage in something new and unexpected. I wanted to feel raw and unprepared. I suddenly (and belatedly) hit on the notion that I needed to begin living my research, not reading about someone else’s thoughts and experiences. So I left. And, about 28,000 miles later, I became reacquainted with myself and discovered that I have an affinity for the ruin, non-sites and discarded objects. I spent most of this travel gathering—sometimes objects, if they were portable, but mostly images and video that became the foundation for a large visual database I call Property (2010 – ongoing).

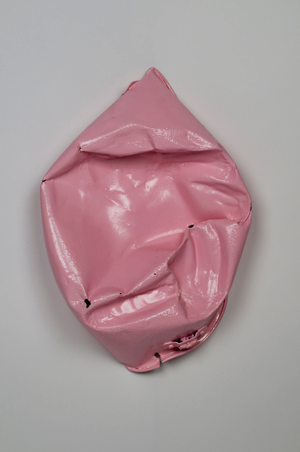

Property_01, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

Property_02, 2011. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

Property_06, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

I now consciously consider and actively seek out the abandoned and the discarded. For me, they are visible markers of change. They’re remnants held in suspension that signify a shift in value, as well as their place in time. Things and places that circumscribe our daily activities engage an open-ended future, or as William Viney says, a ‘functioning future’. [1] Because of our co-dependency on these objects, we project onto them. I buy certain things because of how they will be utilized or how I imagine they will affect me in the future. When an object or place is no longer useful, this forward projection is reversed: it is now in the past, it has become waste. Because of this, it has also been rendered invisible: out of sight, out of mind. Out of mind, out of sight. Empty of purpose, I can now consider its formal qualities as raw material, but a very particular raw material that is both new and an indicator of past use, past value and past purpose. When something has been severed from its context and is no longer bound by function and ownership, this anonymity and ambiguity renders it pervious to the imagination. It becomes raw potential for the scavenger and artist, to be customized in any way they see fit.

AB: Clearly, you take into account the market value of these ruins. Since time and context are important in considering the economic value of electronic media, do you think about them in your work? How does obsolete, nearly obsolete or old technology become fodder for you work? Is an iPhone 4 or Samsung Galaxy old, or just ruin?

HS: I take use value into account far more than market value. I respond to function (a crutch for the body, a stuffed animal for comfort) and the context within which it was used (the home, a construction zone, a hospital). As mentioned in my response to the previous question, I respond to visual evidence of a shift in use value (crushed, tangled, fragmented, stained). This quote by Karl Marx emphasizes the value of use when considering the commodity:

A product becomes a real product only by being consumed. For example, a garment becomes a real garment only in the act of being worn; a house where no one lives is in fact not a real house; thus the product, unlike a mere natural object, proves itself to be, becomes, a product only through consumption. Only by decomposing the product does consumption give the product the finishing touch.[2]

Market value doesn’t even come into play. We purchase objects that either satisfy a presumed need, add to a sense of self and/or make us feel better about ourselves. When their ability to satisfy these needs is ruptured and they no longer ‘do a good job’, I become interested. Their original purpose no longer relevant, these untethered objects now have a certain atmospheric power that compels and speaks of the body. The manner in which I encounter the everyday objects I find for Property instantly reminds me of the deterioration that ultimately lies in wait (both with the objects and my physical body): a stained mattress slumped against the side of a garage, a crushed cooking pot near a homeless camp at a Superfund site by the river, a mutilated grocery cart caught in a tangle of blackberry bushes in my neighbor’s side yard. These become the catalysts for the work.

Superfund, 2010. Cook pan, paint. Image courtesy of the artist.

Property_05. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

As for older electronic media, like an iPhone 4 or Samsung Galaxy, I don’t think that objects with built-in planned obsolescence can ever be considered ruins because they were designed to fail. Their lifespan, in terms of the shelf life of a commodity, is way too short to ever become what is considered a peripheral ruin. They began as ruins. (And how likely is it that you’d see an iPhone discarded in the gutter anyway?)

Property_08, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

AB: Can you expand on the idea of ‘peripheral ruin’?

HS: As I built Property, I quickly found that I am not drawn to the designated ruin that is forever maintained and held suspended in time. Instead, I am compelled by the peripheral ruin: all of the detritus on the fringe of the tourist attraction. I take note of the stuff caught in the chain link, shoved between buildings, rolling down the street and peppering the gutters. If you’re paying close attention to the center, you don’t notice the periphery until there’s a disruption. These dots of material and color compel me. When I was in environments far from the comfort of home, I became aware of the notion of perceptual blindness, a phenomenon that makes it difficult to understand what one sees in a place disconnected from all that is familiar. As you experience this rupture in visual understanding, you have to work harder to see. Ultimately your vision becomes more acute. Having to consciously observe afforded me the perceptual clarity to see a cardboard box again for the first time.

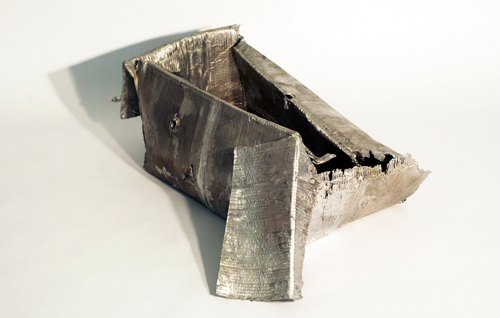

Help Yourself, 2007. Cast aluminum. Image courtesy of the artist.

Property_04, 2011. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

Property_03, 2011. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

I also describe these objects and places as existing in a sort of living death, as we recognize them for what they once were; they no longer do what they once did, but they haven’t been hauled away to the dump. The Salton Sea is one of those places; a crushed metal shed in my neighborhood is one of those objects. They still exist in our world, though they mostly go unnoticed, and for me they have this uncanny ability to instantly remind me of my own mortality.

Property_09. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

AB: Does traditional art conservation or the preservation of human bodies interest you at all? Does either inform your practice?

HS: I don’t consider art conservation at all, and I’ve not thought about human body preservation directly until now, but your question has made me realize that I have maintained an indirect interest in the subject for a long time. A few years ago, I was speaking at Cranbrook Academy of Art, and a few students took me on a field trip to the Packard plant. I had never fully encountered this scale of architectural decay until that moment. Afterwards I began to deeply consider why people are so drawn to benign neglect. Beauty is complicated, and sometimes the internal shift that can happen when experiencing moments like this can be tinged with sadness, disbelief and submission. I began to equate the plant with the things we are typically not allowed to see, like watching the body rot. The Packard plant allows us to methodically bear witness over a long period of time.

Packard_01, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

Packard_02, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

I recently read Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads by Stephen Asma, which emphasizes the craft of taxidermy and natural history exhibition design. Preservation allows us to satisfy our impulse to understand the unknowns in nature through close inspection, dissection and categorization. And while Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads is about preservation for exhibition and scientific research, Mary Roach’s Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers is about the exhibition and study of decay. She details what happens step by step in the decomposition of the human body depending on its final context, whether as an object of study for scientists to research the rotting process, as a stand-in for the effects of a car crash, or for engineers to test the efficacy of footwear when encountering a land mine. Her wit makes these potentially disgusting notions accessible, as evidenced in the first sentence of the book: ‘The way I see it, being dead is not terribly far off from being on a cruise ship. Most of your time is spent lying on your back. The brain has shut down. The flesh begins to soften. Nothing much new happens, and nothing is expected of you’. [3]

Property_10, 2010. From the Property series. Image courtesy of the artist.

AB: How do you cover things up to preserve them or to create the sense of their being embalmed?

HS: In the studio there are several methods I typically employ, each with their own agency. I embellish, alter, skin, re-fabricate and re-cast. After the fragments are gathered, a certain slowness sets in. I spend time with them in the studio, I endlessly arrange them in space, prod and slightly alter them until I decide which actions to take, if any. One of the techniques I frequently utilize is casting. Casting a recognizable form in a material that is antithetical to its function forces you to renegotiate your understanding of the object: a wooden crutch cast in silicone can no longer support a body, much less itself, thereby exacerbating the notion of fragility.

crutch, 2010. Silicone. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

Iphigenia, 2013. Stuffed animal, tack. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

Recently I’ve been exploring different ways of skinning parts or the entire form with paint, flocking, chrome, concrete and/or wax. This can result in embellishment, like drawing attention to the interior of a flattened emergency road cone that resembles the interior of the body, or abstraction, as in the case of two desk lamps encased in a sludge of concrete and wax so that they begin to slip into an ambiguously uncanny form.

Augenblick, 2012. Road cone, paint. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

Phase Bubbling, 2013. Strainer, chrome paint. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

The next time you see me, 2013. Elmo doll, flocking. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

Because of their context and the fact that they no longer function in the way you originally understood them, you have to shift your relationship to them. And when they’re placed in a space where you are only allowed to look, and not touch them, you become aware of them in a different and more engaged way. Their brokenness, the evidence of past use and their pathetic state allow the viewer to empathize and begin to think about their own body. Therein lies the transference—the body becomes an object, and the object a body. In a sense I am bringing these fragments closer to the viewer.

Untitled, 2014. Chair, exercise ball, plaster bandage, shellac, flocking. Image courtesy of Stephen Funk.

AB: You also teach. How does that inform your practice?

HS: I always aspired, professionally, to a career that includes a studio practice and a teaching practice. And even though this probably sounds like an inflated teaching philosophy, it’s sincere. I’ve always felt that it’s the role of the instructor to stay current in pedagogy: to participate in workshops, residencies, collaborative creative endeavors, conferences and classes—even if those classes are bee-keeping and beginner’s Mandarin. I believe it’s critical to show students through personal practice that one’s education never ends, and to encourage a spirit of discovery and experimentation. Sometimes I wonder how much effort I would put into staying current with contemporary art if I weren’t teaching. Would I have read Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture by Tim Ingold or Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things by Jane Bennett this summer if I hadn’t been thinking about how the information would impact the students in Applied Craft + Design, (Oregon College of Art and Craft, Pacific Northwest College of Art). AC+D is a two-year graduate program in Portland that encourages students to make original work with an applied purpose. I am constantly pushing them to explore material with wild abandon—that is, to think through making which is less theoretical and more experiential than traditional design. Both texts, Making and Vibrant Matter perfectly reinforce this idea. I love the fact that after grad school I never stopped being a student, but now it’s even more intense because the knowledge I gain is not just for me and my practice, but also for classes such as Critique Seminar, Professional Practices, and for casual conversations with students during happy hour at the Bison Building (where the graduate studios are located).

AB: What’s on the horizon for you now?

HS: A pillow cast in glass, a full color catalog, a sound piece using Google Translate and beginning Aikido. Sound bites aside, I have a solo show coming up at the Art Gym at Marylhurst University called Botched Execution: Selected Works by Heidi Schwegler 2004 – 2015. It’s been an informative exercise to have to revisit (and in some cases re-fabricate) older work, and to place it all within the context of what’s happening now in the studio. I feel as though I’m the last to realize I’ve been asking the same questions all along.

[1] Viney, William. Waste: A Philosophy of Things (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 8.

[2] Candlin, Fiona and Guins, Raiford. The Object Reader (In Sight: Visual Culture) (London: Routledge, 2009), 406.

[3] Roach, Mary. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers (New York City: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2003), 9.

Heidi Schwegler explores a wide range of materials in the service of her subject matter. She is drawn to the remnant and the discarded and is interested in modifying such existing objects in order to give each piece a new sense of purpose. She has participated in numerous shows, including exhibitions at the Co/Lab Art Fair (Los Angeles), Raid Projects, (Los Angeles), Platform China (Beijing), Scope Art 2004 (New York) and the Hallie Ford Museum (Salem, OR). Schwegler is a Ford Family Fellow, received a 2010 MacDowell Colony Fellowship and several RACC Individual Project Grants. She has lectured on her contemporary art and design work at institutions such as the Burg Giebichenstein (Germany), Cranbrook Academy of Art (Michigan) and Kendall College of Art and Design (Michigan). Reviews of Schwegler’s work have been published in Art in America, ArtNews and the Huffington Post. She earned her MFA from the University of Oregon and is Associate Chair of the MFA in Applied Craft + Design (OCAC/PNCA). www.heidischwegler.com

Avantika Bawa is an artist living in Portland, Oregon, and New Delhi, India. She is Art Editor and co-founder of Drain: A Journal of Contemporary Art and Culture. avantikabawa.net