Glen Snow

All images by and courtesy the artist.

His voice had long thinned, even before it went to the grave, dissipating into dusty pages along with the formalist spell and paternal hegemony it cast. I still remember, though, wondering at how Clement Greenberg could consign the medium of paint to a notion of the logically ‘flat.’ Although he was contemplating how the support uniquely conditioned what painting could be, I guess he was looking from on high, looking through specifically optical and transcendent lenses constructed to focus on painting’s reflexive possibilities. Yet he missed the lumps, all the goop, the ejaculate, the congealing polymorphous perversity of the medium. It must have been oppressive to live with that flatness of painting, in denial of all that facture, excess and the medium’s ability to thickly slop and dollop into the space before us.

As Much Bird as Flower, 2016, wood, acrylic, builder’s bog, pigment powder, and drawing pins. 200 mm x 200 mm.

Thickness would be my term of engagement: a thickening that could push into the literal space of a room. Painting could swell outside its normative support, push past its optical constraints in two-dimensions and into the tactile space of the three-dimensional real. Of course, to talk of thickness is to insert Hurbert Damisch’s alternate reading of Modernism into its history. If the medium is released from its reductionist or essentialist past, then new bearings might be set for thinking the various currencies of painting.

Aporia, 2014, wood, builder’s bog, acrylic, graphite. 260 mm x 220 mm.

As translated and expressed by Yve-Alain Bois, in his formative Painting as Model,[1] Damisch appraised Modern painting as having invented “a new thickness that would no longer borrow from the old academic recipes”[2] In recycling this idea, my work in part could think forward the possibilities of painting as a thickened object, which Damisch had compared in significance to the development of perspective for the Renaissance.

This thickness must include the structural support of the painting, which is where the French word tableaux has certain advantages. A tableau spoken of in the French is literally translated back into English to mean ‘painting.’ But as I have said elsewhere, this French word for painting,

carried a concrete and obstinate original meaning… The philosopher, Hubert Damisch, ruminating on “The Trickery of the Picture,” had remembered the word shared its etymological roots with other objects like tables and tablets. This inference was always present to its meaning so that he could speak of a tableau as “an object, a plane, a flat surface of wood or of canvas…something like a table, but one that is placed vertically.”[3]> He goes on to describe it as a metonym, since as a “base for whatever one may wish to inscribe or display on it,”[4] this base, or panel, or plane enacts an idea of the total artwork.[5]

Gablissvlad, 2016, wood, acrylic, screws. 555 mm x 270 mm.

The concrete aspect of a tableau as a board or panel led me to initially think about my own painting as tablets, as something notably to stand before, and not merely to see. Furthermore, as I have explained in the catalogue, More Than a Picture, a

focus on material is, therefore, a content that ushers in phenomena of the real world to the plane of image so that it is indeed, even in its reductions, more than itself. A painting’s formal relations are no-longer merely internal, or ‘pictorial,’ alone, but also, and most importantly, ‘literal’ – to reverse the terms in Fried’s essay where “Art and Objecthood” were to be seen as mutually exclusive arenas. To speak of … materials in terms of ‘objecthood’ is to attend to the ‘theatre’ of light, shadow, space, weight, body, placement, temperature, and other elements of experience that attend the confronting of an object.[6]

Lobe, 2015, wood, acrylic. 485 mm x 540 mm.

I further think of these ‘tablets’ then, as the physical placements of actions. Not isolated actions, but like the gerund of ‘painting’ itself, a moment of pause – a verb stilled – of the relations and mediations that emerge in the immediate moment of the object. This object is an ‘index of agency,’ as phrased by anthropologist Alfred Gell.[7] As such

Effects of any agency are both registered and de-registered along a continuum from the deliberations, emotions, habits, social contexts of the body, to the material constitutions, mediums, environmental and meteorological phenomena that arrive at the event of the artwork. If a subject’s agency is about an ability to cause actions, then this is not seen merely as inhering in the body of the artist, but also in combination with mediums, social practices and phenomena that may arise in the studio.[8]

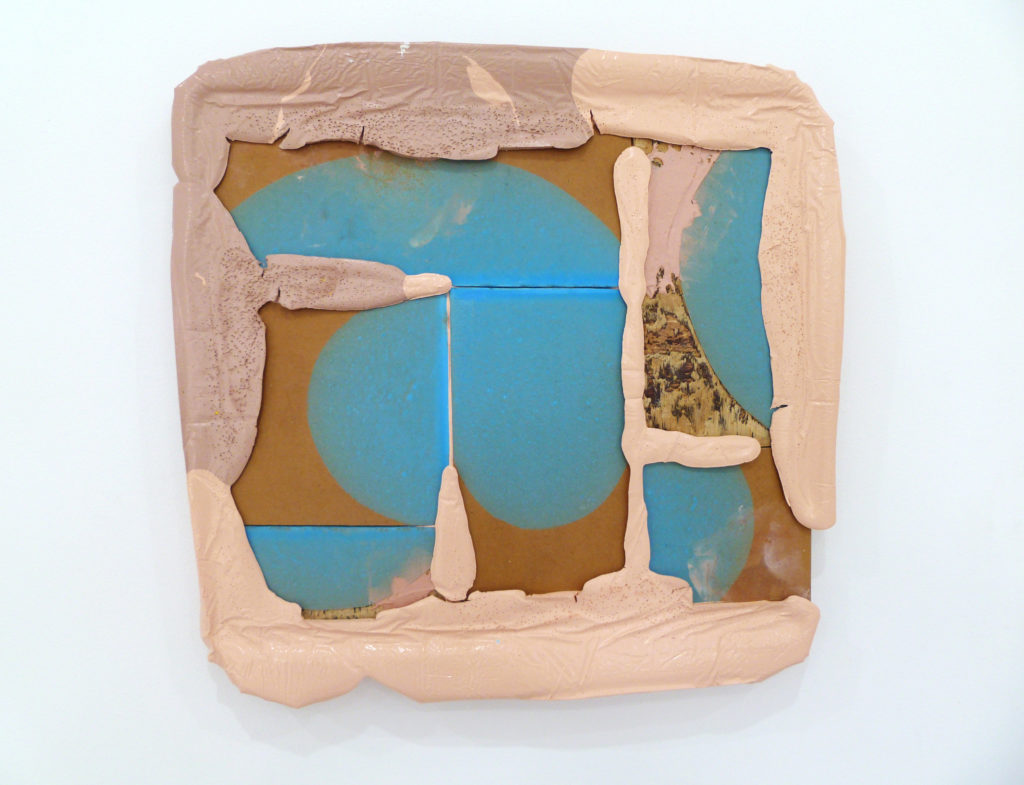

Flesh Bound, 2016, wood, builder’s bog, acrylic. 420 mm x 435 mm.

As put forward in the opening paragraphs of my catalogue essay, More Than a Picture: The Painting as Object,

Such painting, focused in on its matter, has here been termed the paintingobject as a way of distinguishing its framing from within the broad practice of abstraction. Abstract painting in its various forms often presents a certain self-containment, a determining that is without reference to the world. As such, it has been a practice often metaphorically given to the rarefied landscape of the mind: to rational and spiritual schemes of geometry, moral ideas of essence and purity, colour-fields of feeling, gestures of individual genius and dreamscapes of imagination. This mind adrift on the canvas, could be seen to echo the function of abstractions in philosophy, where there is a pursuit of some universal understanding without reference to the actuality of three dimensions, or the full-colour existence of objects in space and time. The paintingobject, by contrast, reminds us it is in the world and of it. Its currency is not our mental transcendence, but our embodied immanence.

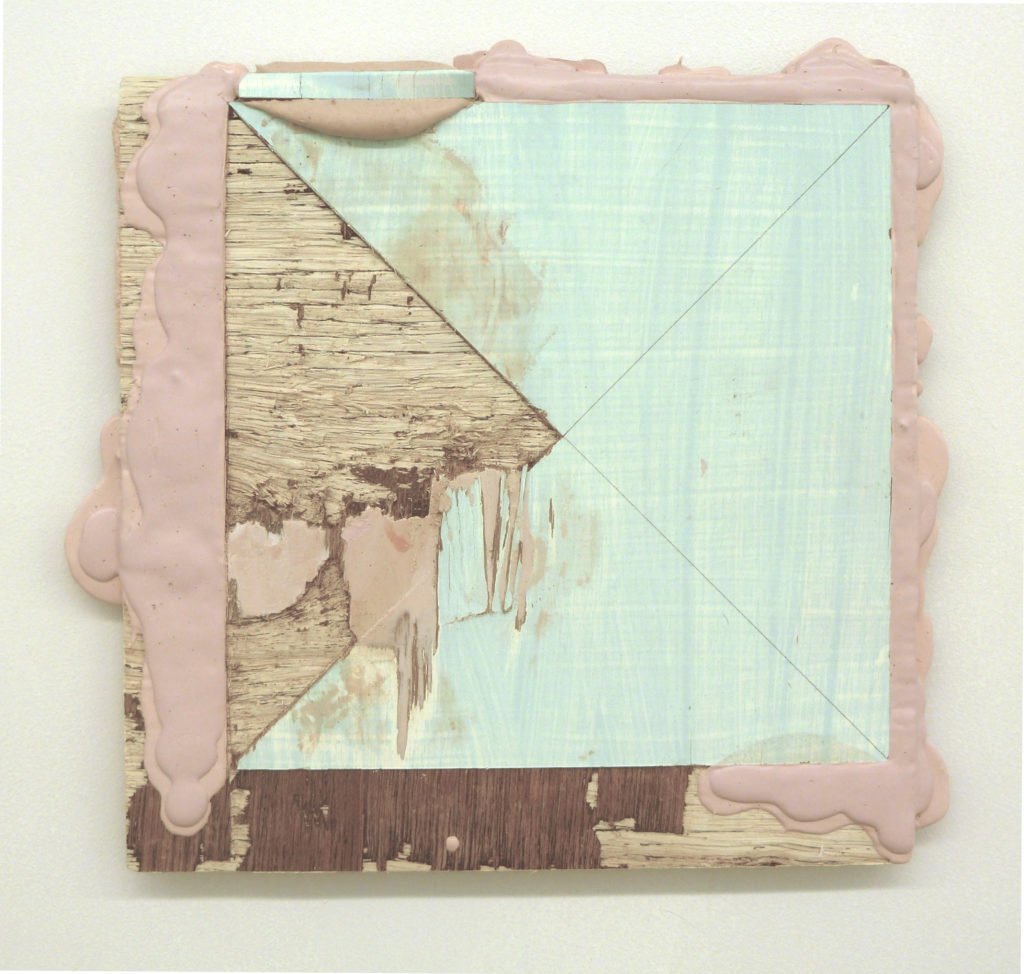

Pattern for Paper Dolls, 2013, wood, acrylic, builder’s bog. 250 mm x 270 mm.

At one level the artwork is positioned within the ordinary, divested of any finessing or crafting derived from within fine-arts traditions, taking cruder approaches that make use of ordinary material, particularly building-trade material. At another level the work is a kind of ‘painting in pieces.’ Each tablet is a thing of parts: raw fragments of painting. I’ve taken my lead here from the art historian Jean François Chevrier, describing Théodore Gericault’s subversive play on making studies of severed limbs and corpse fragments and then presenting them as if they were complete in themselves, as tableaux portraying a narrative of ‘love, eroticism and death.’ Eugène Delacroix, critiquing the work at the time, had described these as morceaux de peinture or ‘pieces of painting’.[9]

In French the verb morceler means ‘to parcel out’, ‘to break up’, ‘to cut up’, ‘to divide into portions.’ It is this sense of arranging matter as morceaux, as pieces, or morsels that I try to make English-sense of, focusing on an idea of cleaving – in both senses, as dissecting/cutting and as adhering/combining. Paint has been completely rethought as something functional like glue, sealer, or filler.

Tongue and Groove, 2017, wood, builder’s bog, acrylic. 370 mm x 410 mm.

The painting Functioning Form was an early key work made in 2013. The title of this work makes reference to an old Modernist dictum, “form ever follows function.” Unlike the office buildings Louis Henry Sullivan wrote this about, this work does not imitate the dominating clean lines of the architecture and design it birthed. Yet it is functional, the paint acts as adhesive, in that the assembled parts are literally glued together with the paint, and in doing so the wood and paint together, simultaneously make the painting. The emphasis is quite literally focused on the construction of a concrete support and plane as opposed to a pictorial surface where its ground would normally disappear. Paint however, seeps and licks through crevices, blooming like mushrooms around edges. The body is indexed here through smudged finger-prints and seems to be mimicked by peculiar tongues lapping or sucking at the space in front. This is more matter than form though, having found shape through pressure and gravity.[10]

Functioning Form, 2013. Acrylic, masking tape, panel pins, wood, 275 mm x 240 mm.

[1] Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 1990).

[2] Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model, 251.

[3] Hubert Damisch, “The Trickery of the Picture”, in Painting At the Edge of the World, ed. Douglas Fogle (Minneapolis: Walker Art Centre, 2001), 166.

[5] Glen Snow, More Than a Picture: The Painting as Object (Auckland: Index Press, 2019), 14.

[7] Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

[9] Jean François Chevrier, “The Tableau Form: Methodology and Composition Part IV,” YouTube Video, 27:33, February 1, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKwCdVyEItc.

[10] I have partially quoted myself here describing a later work in More Than a Picture: The Painting as Object.

Glen Snow is an artist investigating painting as an object; as the concrete ‘paintingobject.’ He lives and works in Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, having gained an MFA (First Class) from Elam School of Art, University of Auckland (UoA) and a BFA (Hons) Painting from University of the Arts London (UAL), Camberwell College of Arts. Glen Snow is a current PhD candidate at the University of Auckland (UoA).

Until recently, Snow has exhibited at Antoinette Godkin Art House, Auckland, with such exhibitions as Would Not Frame and Fat Yellow. 30 Upstairs, Wellington, showed his work in Thick & Thin, and he has been part of selections for Grid / Colour / Plane at Malcolm Smith Gallery, Hyperbolic Gesture, Free Speech and Rematerialised all at DEMO project space and On Hold to Read at Wallace Gallery Morrinsville. He has been commissioned for the Project Wall at Te Tuhi and been a finalist in the touring exhibitions of the TSB Bank Wallace Art Awards. Snow is held in collections there at the Wallace Arts Trust, as well as within a number of private collections. In addition to writing on art and reviewing exhibitions, Snow has helped coordinate and curate shows, such as Materialised at Two Rooms gallery, and Wallace Gallery Morrinsville, and Painting Now: Out of Elam at The Vivian and then TSB Bank Wallace Arts Trust.