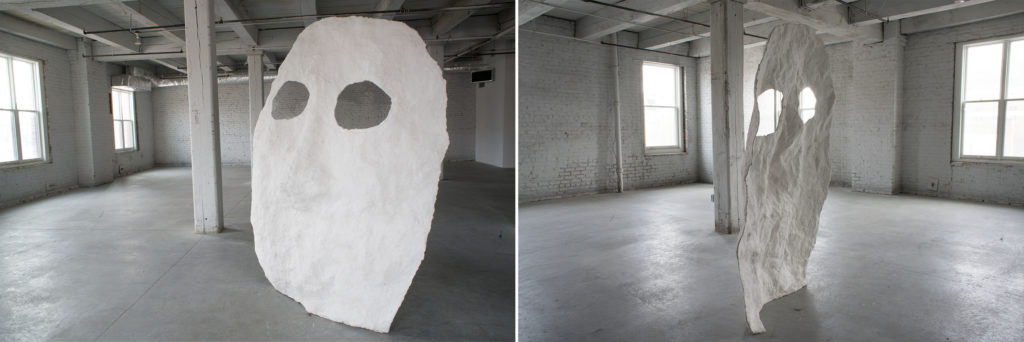

Jess Perlitz

Masks can turn us into beasts, gods, and kings. They propose the fantasy, even if just fleeting, of our being something else. Masking is an act of concealment that makes identity illegible, a transgressive undertaking to seek agency and power. The concealment can also be a form of erasure, but I don’t mean the kind of erasure that is an obliteration, rather, an erasure that is a form of survival; an erasure that prevents legibility in a way that can be both powerful and erotic.

In some ways, we are always masked. I am made by you; my intersecting and sometimes colliding identities formed and reformed by those around me, my conception of self forever interdependent and co-created. This corresponds with how I turn to art, not as a way to adore an image, or with its help to learn what should be adored, but rather to understand how we adore and why.

There is a history of sculpting heads that tells us stories of power; imperial portraits and venerated gods alike functioning as signifiers of authority, wealth and values. There is also a history of the head as a devotional object – a place to direct the prayers of the faithful, a history propelled by expectations and questions of life and death and ultimately a distrust of the material world: questions of erasure that seek a container.

Our museums house countless headless torsos, their missing heads either long gone or far away. Over time necks prove fragile and they break, and it also happens because when it comes to sellable artifacts, two reaps more than one. Sometimes we break sculptures, seeking an erasure that might help us imagine something else. As it turns out, the destruction of statues is an ancient way to wage war. Iconoclasm, the act of image breaking, is a recurring historical impulse of ours to break or destroy images as a tactic for both an undoing and a remaking. The headless statues we hold onto are artifacts, but we could also consider them surrogates, deputized to be reminders that our fragmentation and erasures are in fact of our creation.

Jess Perlitz’s work is informed by our formations of landscape and the body’s place within it, finding points of desire, incongruity, and disruption. Born in Toronto, Canada, she is a graduate of Bard College, received an MFA from Tyler School of Art, and clown training from the Manitoulin Center for Creation and Performance. Perlitz is currently based in Portland, Oregon where she is Associate Professor and Head of Sculpture at Lewis & Clark College, and most recently, the co-leader of the year-long Portland’s Monuments & Memorials Project. Perlitz was named a 2019 Hallie Ford Fellow, won a Joan Shipley award, and received an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her work has appeared in playgrounds, fields, galleries, and museums, including the Institute for Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, Socrates Sculpture Park in NY, Cambridge Galleries in Canada, De Fabriek in The Netherlands, and aboard the Arctic Circle Residency. Her project, Chorus, is currently installed at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, PA as part of the museum’s ongoing artists installation series.