Andy Roche interviewed by Alexander Stewart

Interview conducted in person, January 16, 2009

Transcribed by Chelsea Tonelli Knight

My first encounter with Andy Roche’s work was in the fall of 2004, when he presented an in-progress version of his film Born to Live Life at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where we were both in graduate school at the time. Andy prefaced his film with some thoughts on charisma and psychedelia, topics central to his work. Interspersed throughout his talk were a handful of video clips that he used to build a framework for his film – an excerpt from John Boorman’s Zardoz, a clip of Harvey Sid Fisher performing one of his Astrology Songs in a weird, local-access-cable-level, lounge-act, Klaus Kinski glaring intensely during the raft scene in Werner Herzog’s Aguirre The Wrath of God, and a section from Sun Ra’s Space Is the Place.

When he finally screened Born to Live Life, which is probably most concisely described as a psychedelic documentary about Andy’s friend, the comics artist Victor Cayro, I knew I was having one of those moments, perhaps best relegated to some kind of interview with a critic in honor of a dead film director for a dvd extra, in which a person later recounts having their entire conception of art come unraveled over the course of 20 minutes. At the time, I was immersed in work based on minimalistic conceptual purity and clever formal experimentation, along the lines of Tom Friedman or Tim Hawkinson. Andy’s film was something completely different than what I thought I was interested in. It was funny, off-kilter, weirdly sad; at times stretching on endlessly and at times projecting an undeniable magnetic charisma. I knew immediately that it was coming from a personal artistic philosophy that I absolutely needed to understand.

I think it took me about 2 years to fully come to terms with the scope of the film, and to internalize the unique aesthetic language Andy uses in his work. I frequently say that Born to Live Life is one of the two or three most substantial pieces of cinema I have seen come out of Chicago since I have been here, and I continue to stand by that assertion. It’s a truly remarkable film, the product of a truly remarkable mind. Andy and I have become good friends since my first encounter with Born To Live Life, and his work and life philosophies are consistently some of the most stimulating intellectual and emotional engagement I encounter anywhere.

I have recently been thinking about what the shifting political landscape in America means for artists, and so I met up with Andy in January 2009 to talk it over, and to get some of his philosophies on psychedelia and politics on tape.

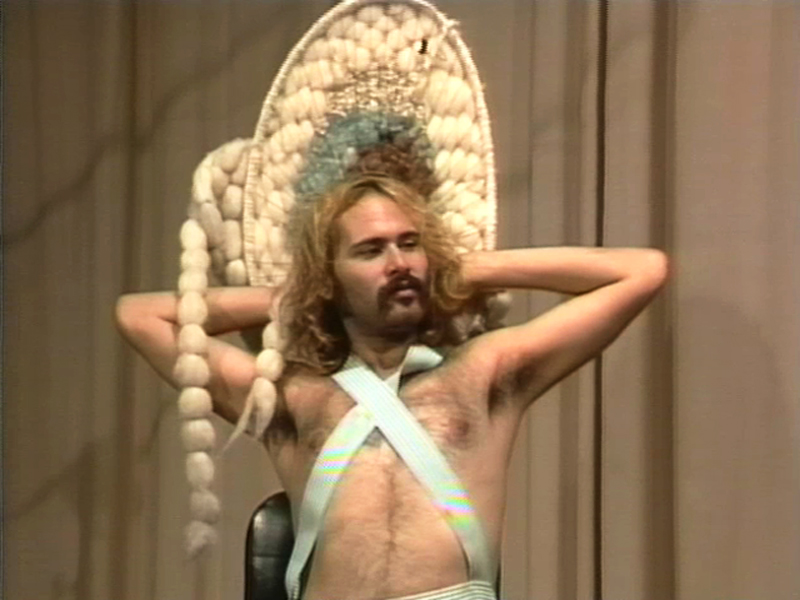

Still from Born to Live Life, Video, 23:00, 2005.

Alexander Stewart: I guess the place to start is, I’m curious to hear a little bit about sincerity and psychedelic or New Age culture. We’ve talked about this in the past in terms of there being a first generation of this stuff, in the 60’s and 70’s, and it seemed like it actually mattered in a different way than it does in contemporary art or in contemporary music. There’s a different relationship to sincerity in that kind of work.

Andy Roche: Well, it goes through changes. Immediately when I think about sincerity and psychedelia, I guess I start thinking about the people who got involved in psychedelia that weren’t necessarily of the sort of 70’s kind of Yes type of thing, and elves and misty mountains and all that kind of stuff. So for example, I think about sincerity, I sort of think about a band like The Fugs, who I think are very sincere, in a sense, at the same time they’re like big goofballs. Right away you get into the sort of issue of “what is sincerity” and I think on that level, though, The Fugs are seriously goofing, right?

AS: Well let me just rephrase it, or put it in some clearer terms. So I look at somebody like The Fugs, for example, as being very serious that what they’re doing really matters. I think that in a larger scope there seems like there’s a sincerity to late 60’s, early 70’s culture which is like, they feel like they’re actually going to accomplish something with what they’re doing. They feel like there’s a moment of cultural sea change at hand, and they’re seeing either an expanded consciousness as being very important to them, or moving against some sort of political situation through their work. Versus someone like Davendra Banhart today, for example, who I think puts on this sort of hippie style, that I just, try as I might, I don’t see it as coming from a place that it feels like he has the same relationship to the politics of his work, or the politics of that style, that people did in the late 60’s, early 70’s. I guess that is more what I’m asking about with “sincerity”.

AR: Well, I think part of it is, Davendra Banhart’s taking a pose on. He’s striking a pose of some sort of update of Marc Bolan, right? I go back to Davendra Banhart a lot, subject myself to videos of him online. Every couple of weeks I’ll make myself look at something of his because he is kind of, kind of troubling, because it almost works. I really did actually like his first record, and I remember when he was first coming around, I think there was a tour that he was on with Joanna Newsom and they were just playing house shows in the midwest. They were basically just kids, like everybody else, before they were big stars. I think I felt immediately kind of resistant to him, mostly because I could see he has a famous person’s name. He kind of has a name as if he was named as if he’s a Thomas Pynchon character, like Mucho Maas or something like that. So, on that level it’s like, “Andy Roche” is pretty good, but it’s like, 25% there.

AS: You can always get a new name.

AR: I need a new first name or something… but so I think on that level, it sort of seemed like even with his name, which I guess is his given name, it seems like he’s sort of striking this pose, right? And as he’s gone through the motions of his career, he actually has followed the artwork of Marc Bolan from Tyrannosaurus Rex or even John’s Children. The kind of psychedelic troubadour “lonely guy” thing. Kind of like a Syd Barrett that’s not going to kill himself. A Syd Barrett that’s happy to talk to you and wants to hang out. And then he sort of evolved into the T Rex type of over the top thing. But all those things are poses, they’re all artificial. It’s funny, because if you compare him immediately to someone who is legit, which is what I’ve been comparing him to, Marc Bolan, I mean Marc Bolan’s stuff is… kind of stupid. For example if you watch Born to Boogie, the feature film that he did with Apple films, it seems like psychedelia on the level of like Boorman’s Zardoz or something, which I really like, but I like it because it’s really ham-fisted and theatrical and artificial and it seems sort of transparently false, in kind of an interesting way. Whereas Marc Bolan’s sort of pixie-ish, sprightly, party-man persona thing that Banhart has going is pretty convincing, despite the fact that it seems completely contrived. It’s a convincing pose.

I think that the issue of the pose is really important in psychedelia, because there’s the idea of that pose being sort of a speculative version of yourself. And I think that what’s frustrating about Davendra Banhart is that his speculative self is somebody else, and not like somebody else that is some sort of creature of the mind, like an invention. His “somebody else” is somebody who already lived 20 years ago, who was Marc Bolan. Right? So his speculative self is like “what if I got to be Marc Bolan now, for less money,” or something. It’s something like that. I think that what’s frustrating about that is it’s a legitimate way to go.

AS: Well yeah, not to put the image of Banhart on the spot as the guy we evaluate to pronounce whether there could be a possible sincere contemporary psychedelia or not, but I guess the question is, maybe in a broader phrasing: Our generation’s relationship to psychedelia, and then our parent’s generation, that’s maybe the key question here. It’s our generation as artists or musicians or whatever, revisiting. I’ve always felt this weird issue is at stake, like, “Didn’t our parents, when they were our age, weren’t they living in a cultural environment that’s what people our age are trying to recreate now?” and: “Didn’t we do this already?”

AR: Well I think something that’s kind of interesting is that psychedelia happened during a time period when obviously things needed to get done. So why is it important that this sort of, what seems to be fantasy-based, or distraction-based, kind of spectacle-based, type of culture comes up, at the same time that really important things need to be done by the youth, right? Which is I think one reason I think it’s important right now, because it seems like, yeah, you can make a direct parallel to the last eight years, and I don’t think you even want to give that credit solely to Bush. I think that there’s this aching feeling that all the people in my generation have been aware of their entire lives, about environmental collapse being on the way. I think things that seem like paranoid things you’ve been hearing about for 20 years are just coming to be true now, and I mean it’d be easy to get wrapped up in a kind of paranoia which people have.

Okay, so you have this idea of people going into fantasy at the same time that they need to be doing serious things. One thing I think is interesting about separating psychedelia today from a psychedelia then — and of course I think real psychedelia kind of continued on, probably precedes the 60’s, of course, and continued on after that—but if you sort of imagine a couple of idealized types of people, from the 1960s. One person I kind of idealize, my parents, and people I knew when I was growing up, and people in the social milieu of my parents, and people I just sort of saw around, and people over in Iowa City. A lot of those people I knew were in a sense folkies more so than they were hippies. Probably a lot of people, like for example The Fugs, they were of course definitive hippies, but they weren’t hippies as we think of them now, or as I think, perhaps, Davendra Banhart thinks of it now, where a definitive hippie is like some sort of Mark Bolan type of drugged-out elf-man. Whereas the actual hippie was some sort of action-based beatnik with longer hair. But, obviously there was sort of a real psychedelic person, as a type, the person, who was, I guess tripping all the time and that kind of thing.

So if you imagine the psychedelic pose as sort of a cultural moment, you have people sort of engaging in the culture of their time, psychedelic art, psychedelic music, psychedelic popular film, even to a lesser extent TV shows are like vaguely, psychedelic, like, I don’t even know, like Laugh-In or something like that. You have this idea that this is a culture where people recognize this sort of social or artistic pose, right, like, kind of the “far-out person,” but you can equally imagine that same person being the guy in the kind of milieus I sort of remember. I guess this was the early 80’s, of course, but it’s not like things just stopped in the 1970’s or something, like everyone just decided not to be like that at all anymore, and no one ever did that any more. That same person that may have thought of this sort of psychedelic culture as the sort of the entertainment aspect of the culture, and the real culture were all sorts of things, like, sustainable farming practices, or someone who did the back-to-the-earth route, or maybe even being like a working stiff person, or a jobbing person that made his own house. Another thing I always think about is, these guys, all these guys like my dad, like, making your own cabinets, and building some kind of vehicle that you use on the weekends.

AS: Solar powered, Whole Earth Catalog kinds of things.

AR: Yep, all that kind of stuff, right? And so the thing is that there were real things to do. There were people who were involved in social justice things, people that evolved in the 1980s into the No Nuke movement, or people that evolved into the peace and justice movement regarding Central America in the 1980s. Or South Africa, and things like that. Perhaps, in some ways, a lot of those people became in some ways more mature because they started to think about trying to figure out how you respond to imperialism, like in the form of Vietnam and the Cold War. And to kind of a proactive engagement of the outside world for Americans, right? The kind of politics I was just talking about. So in that time period, I think it makes sense that psychedelia feels like the vanguard of that energy, or some sort of specific outlier of that energy, that same kind of really creative solution. And maybe that’s why like a Banhart doesn’t really make sense, or he seems kind of silly, because Davendra Banhart, the way that he lives differently from the rest of us is that he dates Natalie Portman. The way that he lives differently from us is not that he’s living as a future person, he’s not living ahead of us in time, right?

AS: Although he does have long hair. In your video, The Thorny Path, where you have on a long wig, you told me, “The wig is me, three months in the future.” However long it takes me to grow this much hair, is what me wearing this wig is. Which is like, “future person,” or, “I figured something out”, or self-actualized Andy, Andy on a higher plane because he’s lived like eight more months.

AR: Yeah, and, if you’ve ever grown out your hair, that’s part of what it’s about. It’s this idea that it’s some proof of existence. Right?

AS: Well, also the musical Hair. There’s so much political significance to the long hair. Even that term, “He’s a longhair,” you know?

AR: I think on some level, doing that proves that you’re simultaneously maintaining at the same time that you’re growing. Right? You haven’t cut your hair, so you know that, “I’m still the same person I was yesterday, and I’m still this different person that I was yesterday. I’m still this changing, evolving person.” I grew my hair out for the first time when I was 13, I think, and ever since then I do it every couple of years, because I have that need to occasionally feel that, that kind of… well it grounds you, I guess.

AS: Well let me try to get at what I think is kind of the key here. You’re talking about psychedelia as political, in a certain sense, talking about the No Nukes thing, and people who feel like they’re on the cutting edge of some kind of creative problem solving. And then, psychedelia which I feel like is escapist. And I guess I feel like that’s sort of the key strains here, resolving those two things. When I use the term “psychedelia,” I don’t want to pigeonhole it, because I feel like it’s part of, in a certain escapist way of thinking, a continuity of a kind of culture that’s existed for a thousand years, from medieval fairy tales, to these mystical…

AR: Like a Bardic tradition.

AS: You can trace a sort of a counterculture, “against the squares” basically, going back a really long time. Maybe you start with Romanticism, the Romantic tradition of Emerson, or someone like that. William Blake. That idea of putting the imagination first, that imagination is the way that you deal with certain things. I think if you look at the political implications of an original kind of Romantic movement, it is a reaction to the age of enlightenment, and this belief in empirical progress, that by asking questions in a certain way and solving things and building machines, we can move forward. Well, maybe that’s not necessarily a healthy thing if it isn’t balanced by a way of dealing with things which is inward-looking. This idea of inward-looking-ness and interest in imagination which you can see in beat culture; or jazz in a certain sense has that idea. Then you move into psychedelic culture or New Age culture, these things I feel like are all kind of part of the same sort of tradition. David Axelrod did those two records, Song of Innocence and Song of Experience, which are both based on books of William Blake books of poetry. Which I feel is sort of, in a way working a little hard to make that connection, from Axelrod’s culture, this sort of drug culture of the late 60’s and early 70’s, to classic Romanticism. But at the same time I do feel like it kind of makes sense. He’s trying to ground this sort of inward looking eye, the inward looking-ness, with a historical tradition. To put it in terms of psychedelia, I guess I look at the key issue as trying to balance those two things, the Romantic inward-looking-ness and politically charged outward-looking-ness.

AR: Well, William Blake is a mystic, right?

AS: That’s a good term, mysticism.

AR: I think he wasn’t necessarily the first person to do it, but he kind of became famous for this way of taking a sort of mainline Christianity and expanding it, exploding it, right? And interestingly enough, he’s expanding beyond a sort of personal exploration.

AS: I mean that ultimately though that is what Romanticism is about, extreme subjectivity. It’s about personal centered-ness. There’s people, I guess the term is “gnosis?”

AR: Gnosticism.

AS: The idea of knowing religious truths through personal, ecstatic religious experience. I feel like there’s a certain aspect of Blake and his interpretation of Christianity in that light that bridges over to why I think maybe LSD culture was interested in people like him, because that’s ultimately an extreme personal experience. David Foster Wallace has an essay where he talks about the central issue of an existential contemporary life is, “I’ve never had an experience that I’m not at the exact center of.” And figuring out how to overcome that is ultimately the challenge. I remember you one time saying something that didn’t resonate with me until years later which was that Peter Frampton’s line “Do you feel like I feel?” is the central question of Modernity. Which I think is kind of all about the same thing – Blake, having these probably schizophrenic religious experiences, and putting them down on paper, and, Peter Frampton asking that question into a talking guitar, are kind of two ends of that same spectrum. On one end, bloated, post-psychedelic arena rock, and on the other, visionary religious experience.

AR: Well, and the second part of the thing I think about Frampton is that the answer is given in the form of abstraction, in the form of a guitar solo. Right?

AS: Right!

AR: So that’s the important thing about the Frampton thing. The way he feels, it has to be mediated. I think if you flash forward, a similar figure that’s sort of interested in gnosticism would be late period Philip K. Dick. His last three books, Transmigration of Timothy Archer, Vallis, and The Divine Invasion, they’re all kind of interested in his sort of epiphany experience with sort of gnostic knowledge, in the form of like a pink laser beam that shoots into his head and makes him experience, sort of simultaneously, contemporary Bay Area California and at the same time he’s experiencing kind of like, the destruction of the Temple, and like the 40 years after the death of Christ, right? And Roman Israel being superimposed on top of Berkeley, on some level it seems like it’s probably him losing his mind and having a religious experience. They’re probably kind of the same thing. In good and bad ways, there are good and bad interpretations of that. But I think on one level, I think what’s going on there in those last three books by Dick, it seems like a crisis of confidence in political power, or its ability to change things. So he sort of equates it to the last time there was a Millennial change. The pre-Millennial tension sort of surfaces at that time, right? The feeling that change is imminent. Change should have happened by now. Did the change already happen? And we’re under a holographic existence now that hides the change from us? Or is the change stolen by nefarious powers? Is the change only being experienced by a few, and I was not initiated into the cult deep enough to experience the change?

AS: Have the future people moved on, and am I still here?

AR: And all these sorts of things, right? Like has the Heaven’s Gate crowd, you know, did Hale-Bopp take them away? While we’re all laughing at them in their matching sneakers, are they really all together on the comet, laughing? I think when you talk about any of that kind of gnosis, when you talk about revelation, you’re talking about the revelation of a world picture, of a sort of understandable world system. And I think that’s something that’s really a kind of exciting aspect of sort of psychedelic culture, the idea of kind of personal-sized, or subjectivity-sized world picture. So, I think on some level, psychedelic politics is about, in big and small ways, trying these sort of new experimental pictures, pictures that somehow so challenge our current understanding of our political realities. Perhaps it could be nonviolent, perhaps our political realities could evaporate under the force of a more persuasive picture. Which is one reason why these politics are also visual, and inherently dovetailed with art. So that’s a starting point.

AS: Let’s talk about something that’s inherently inward looking. I feel that Stan Brakhage is not a psychedelic filmmaker, but you look at Dog Star Man. It’s an inward looking film, it’s a film that’s about his imagination and about his closed eyes. The term that people use for Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic is “mythopoeic.” It’s about either reinvestigating an older myth or inventing your own system of mythology. And Smith’s film is just so dense with interrelationships and cosmic metaphors that come from Smith’s imagination.

AR: Well the main character in that film is sort of a combination between acrobat an alchemist. He’s sort of a circus performer who is an alchemist or something, or maybe an alchemist kind of slumming as a musician doing an act, or something like that. There are these sequences where he’s sort of, performing tricks, and sometimes they seem like they sort of fail. And I think that seems to make a lot of sense with who Harry Smith was as a person, from the interviews I’ve read with him. It seems like that’s sort of a big experiment. It’s a great success, also a great failure in all sorts of ways too. I think there’s something kind of cool about that, and it’s maybe a better key film than Dog Star Man.

AS: I feel like they’re aesthetically different, but they were trying to do some of the same things.

AR: Just the assertion of a figure, or the persistence of a figure, in Heaven and Earth Magic makes it easier to talk about, at least without having seen Dog Star Man in a while. In Heaven and Earth Magic, something that separates psychedelic politics from contemporary politics, there’s the sense of play. The sense of seriousness, but at the same time, there’s the idea that you have good faith, you’re going to experiment, you’re going to fail, you’re going to succeed, but by virtue of your continuing sort of magical devotion to experimentation, or alchemist-like devotion to experimentation, you’re going to hit on the magic tricks that are going to take you to the next level. And that’s something that’s going on in Heaven and Earth Magic. It’s interesting about comparing that to contemporary politics, with the preoccupation with sustainability. There’s this idea that we’re going to hit some sort of stone cold groove, right?

So this issue of sustainability is interesting because there are aspects of it in the structure of the Obama campaign, with sort of a decentralized thing. I think there’s some interesting things about a decentralized campaign, with lots of small players making decisions, a very sort of intelligently arranged grassroots campaign. In some ways it’s interesting because the figure was to some extent created by the grassroots support. Of course, Obama and Axelrod knew enough to put the wheels in motion. I think this is interesting because this was the first campaign that my guy won, and it’s the least involved I’ve ever been in a presidential election since I’ve been in high school. This is the one I stepped out of, which suggests maybe they don’t need me, because the one time I don’t get involved is the time my guy wins. With the people I was involved with before, the persona kind of preceded the grassroots movement, Nader and Kucinich, right? Those were my two guys, and in both cases, they’re were sort of like saying, “Hey, I’m a great guy! I need a grassroots movement to bring me over the top! Anybody want to spontaneously carry me through the streets? I’d be up for it. I don’t even eat very much, I’m very light.”

AS: Well, this is a point you made in the past, comparing classic psychedelic culture and what seems to be its logical descendant, New Age culture. New Age culture is essentially based on the model of the drone. It’s a sustainable version of psychedelic culture. It’s why it didn’t go away. New Age culture hasn’t died, it’s just where old hippies retired to, with crystals and stuff like that. There’s a certain aspect to New Age images and design and culture that’s just very strange and inaccessible to me. But when you put it in those terms, that it’s a culture that’s based on the drone, the sustainable structure, it’s suddenly like, “Oh yeah.” Radical psychedelic visionary ideas aren’t sustainable beyond a few big years, and suddenly you’re like “Okay… now what?”

AR: And they aren’t all people who dropped out to live in Taos and Boulder and places like that, or upstate New York. Someone who I think is a very interesting figure, who I had the privilege of meeting briefly this year, who sort of fits very neatly into this trajectory, is Hans-Joachim Roedelius. And it’s sort of a little vague to me, but he has this whole history – he’s East German, and he had some sort of association with Bader-Meinhof Gang, and he had associations with sort of really hardcore leftists in Germany, leftism that’s sort of hard to fathom by American standards. And his band Cluster, which is this amazing awesome experimental psych band, has sort of precursors to New Age sound in it. Harmonia the sort of supergroup he was involved in, with Moebius from Cluster, and the guys from Neu!, the guys from Guru Guru I think. And then, his long solo career, of what starts out as radical synthesizer-based music which is not that different from Cluster, to sort of a career of doing stuff that you can say is sort of the best and the worst of New Age stuff. It’s serious, and it’s good, but it’s also bland, seems to be kind of relentlessly produced, and there’s tons of it.

I think this is interesting, because it seems less like sustainability and more like survival strategies. First of all, can I keep relentlessly creating, and even though Cluster didn’t exactly rock out, but can I keep rocking out like this forever? Or do I have to find a way for an adult man to be outside of society? And I think that the way that they find that is by being outside of time, which is one of the things that New Age music and the Drone kind of becomes.

Still from Born to Live Life, Video, 23:00, 2005.

AS: I remember you said one time that psychedelia is like playing too much Tetris. You’re doing something with your conscious mind that affects your unconscious mind later. It could be playing hours and hours and hours of Tetris, and then you start seeing things fitting together. Or maybe it’s having a mystical religious experience from praying for fifteen hours a day. Or maybe something as direct as taking LSD or mushrooms.

AR: Psychedelia seems in some sense to come from a game-oriented way of thinking. A sort of contrivance. When we’ve been talking about the psychedelic, of course, we’ve been ignoring the fact of drugs’ relationship to the psychedelic. I think the obvious reason we’re able to talk that way is because, and perhaps a hardcore psychedelicist would probably likely disagree with us, I really don’t think the drugs are necessary. What’s necessary is the idea of a contrivance, or a catalyst. The idea that this outlying thing enters, and gives you permission, or perhaps gives you perceptual skills, through some sort of new arrangement of things, to imagine a new world picture.

I think the important thing is this idea of having some kind of ritual or something. Having some kind of performance setup, that takes you into a sort of non-ordinary space, somehow. Something I’ve become really interested in, towards this end, is, authors like the OuLiPo, like Calvino,

AS: And Georges Perec.

AR: And Queneau, and people kind of before that, particularly guys slightly before that, Boris Vian, who I love. All that stuff is a similar sort of idea, you have a transparently stupid sort of setup like A Void, Perec’s book that excludes the letter E, even in translation into English. And that book somehow manages to become a mystery story, where someone’s searching for something that can’t be found, which ultimately is the letter E, which is missing from the text, so it’s impossible to ever find. Which actually ends up being, I think, not that this is the only way to judge something, but, it manages to be a pretty touching, effecting novel, despite the fact that it’s basically…

AS: A gimmick.

AR: Yes, a gimmick. It’s 100% contrived. Now, that said, you could say the drug is a gimmick, or a contrivance, or those words you want to apply to it. And it’s funny because something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, is, for my sort of definition of the psychedelic, is how some things that are considered fundamentally or canonically psychedelic, I think are not. For example, The Holy Mountain and El Topo are not psychedelic films.

AS: Why not?

AR: This is a judgement call. I’m making a judgement on Jodorowsky’s internal world. It may just be some other type of psychedelia that I’m just not interested in, I reserve that as a possibility. I think because the sense of the play is so sublimated, compared to the sense of control. The film is so heavily controlled. The film is so stage managed. The film doesn’t have a contrivance, it’s contrived. It’s this sort of gross approximation of surrealism, and psychoanalytic creation, and mythic creation, and he even finishes, in the case of Holy Mountain, I believe, with the thing where they get to the top of the mountain and, he’s like “It’s all just a film”.

AS: “Camera, pull back!”

AR: Yeah, “camera, pull back!” And it’s 100% horrible. I mean there are cool images, when the woman’s breasts are two cheetahs that spray some kind of thing, it’s pretty wild. But it’s oppressive. Psychedelic stuff should be lighter than air, it should be globular. I just can’t imagine that Jordan Belson, maybe I’m assuming too much, but I just can’t imagine that he would consider himself in the same genre as Jodorowsky. And Jordan Belson is most definitely a psychedelic filmmaker.

AS: When Belson writes about his films, he talks about, initially through extensive LSD use, but then later entirely through yoga meditation, he says something like, “I go to this place and I have these images that my mind shows me, and then because I know my equipment so well, my lenses and my tanks of ink, and my lights and mirrors, I’m able to effortlessly recreate those images that I’m pulling from deep within my imagination, and my mind’s eye, on to the screen.” So he’s sort of thinking of himself less as a creative person and more as a transmission vessel from something his imagination is giving him. Which is kind of an interesting place to put yourself as a filmmaker, to take your conscious decision making out of it, and make it a tool set you’re using to recreate something subconscious.

AR: And I think that that’s a sense of serious play. Or serious investigation. But I think there’s an element of play to that too. And once again, think about sort of key terms here: doing yoga is striking the right poses, sustaining the right poses. This issue of the pose is really important. And obviously the words pose and posture are related, but Jodorowsky’s posturing. He’s not beautifully moving through poses, he’s not experimentally trying new moves, he’s doing a well-rehearsed act.

So if you compare El Topo to Luc Moullet’s A Girl is a Gun, I don’t know if it’s considered self-consciously psychedelic, but it has kind of a psychedelic Western quality to it, an acid Western quality to it. It’s got, oh what’s his name, Léaud is the star of it. It’s a Western so he’s sort of a French cowboy, with kind of goofy pageboy long hair. He really kind of looks more like a fashion plate. I mean he looks great, but he doesn’t exactly look like a convincing cowboy. He’s on the run, there’s a woman, and it just sort of has a sense of play from scene to scene that I think is really fascinating. And what it feels like is that it has a sort of great quality of applying that sort of sense of play of the psychedelic, or of the New Wave, really, to the Western.

My only point about this though is that it is incredibly light. It has a sense of play. It has that sort of sense, not of the “return of the repressed” in the sort of interest in childhood, but this sense that it’s at play with the repressed. It’s not just to have those things overtake you, which is the stupid psychodrama of The Holy Mountain or El Topo, where it’s like things only happen in big waves of awareness. Jodorowsky’s kind of epiphany is sort of the steamrolling epiphany. A role-destructing epiphany. As opposed to the sort of minor hiccups of the synapses that really should be more the business of a more honest version of psychedelia. Because it’s more human. The emotions that Jodorowsky is trying to express, they’re the emotions of a Titan, of a mythical character. They’re not the emotions experienced or the psychology experience by a lowly tripper or the lowly anybody with subjectivity. Which is just stupid.

But going back to another point, about this current music culture, the MP3 culture, this culture of low-rent psychedelia today, Jodorowsky is such a hero right now. He’s having such a period of interest. I’m sure that not since his early midnight movie days has there been so much interest in Jodorowsky. His big article on reminiscences in Arthur that came out a few months ago, was just sort of moronic, probably mostly fabricated, I would guess. He’s macho enough that he would hunt me down and say I’m not a man or something, and hold a gun to my head or something stupid like that. But he’s the psychedelic hero that our generation deserves. Because he’s shallow, showy, has no politics, and you know, I think that’s about it.

AS: Well, “the psychedelia of our generation” is the key to this whole trajectory. Basically, I have this feeling that the kind of psychedelia that makes sense to young people today, artists or musicians, has sort of a direct proportionality to this impenetrable neo-con politics that we’ve had for eight years. There’s a certain sense that there’s an inability for real protest to actually exist, for protest to mean anything from an artist’s standpoint. I mean, what can you say? “I don’t agree?” I think people kind of wore themselves out in about 2003, and it’s been like, “Well what else can you do?”

I mean, there’s still politics, obviously, but it’s sort of established, the position of protest and annoyance and disagree. I feel like there is definitely a whole range of aesthetics, largely psychedelic, but I think in recent times, some New Age aesthetics as well, that I feel like are a direct response to a political environment. The question is, what does all that mean – in the sense that maybe it’s shallow, maybe it’s not shallow, maybe it’s directly engaging with ideas, maybe it’s not – in light of the fact that on Tuesday January 20, we are going to have a new President.

Whatever stock you want to put in this as being a moment of real change in American culture, I think you have to acknowledge that a lot of people are looking at is as “Okay, at noon on Tuesday everything changes”. And I think it sort of puts into question all this dropout-psychedelia. Like, “You know what, noise is fine, noise rock is fine, because this is the only thing I’m feeling right now, because I’m so disconnected from politics.” Or also, “This extended fantasy trip of surrealism is fine because the only thing that’s real right now is me and my subjectivity, because the reality of politics is out of my grasp, or uncontrollable.” And suddenly that stuff kind of feels to me very dated, and kind of like that doesn’t really work right now. It works maybe in 2007, when you still have another year and a half of President Bush. But then suddenly, politics are not the same anymore. Your guy won, you said, and I guess that’s the question: where does that leave psychedelic impulse, whether it’s a posture or whether it’s a sincere psychedelic impulse, when suddenly your guy’s on top, when you don’t need an escapist mentality any more.

AR: Well as far as some of that escapist stuff goes, I would say first of all, for all those people that bought big backlogs of neon paint to be using for the next 15 years, post-Fort Thunder, don’t throw it out, but maybe just start looking at like Peter Halley and some of those guys, and sort of find some other things to do with those bright tones. Beside ripping off Providence in the late 1990’s.

So, what changes on Tuesday January 20? I think hopefully it is the beginning of, as opposed to the death of something. Hopefully it’s the birth of at least feeling like something can fundamentally change. I think the world picture has changed. I think the very fact that Bush seems like this sort of bizarre person that’s hard to remember was actually president, is really really significant. That as soon as Obama was elected, maybe even before he was elected, in November, he was already President. And that’s the hopeful thing. We are ready to cast off the world picture the neo-cons were trying to sell us on, were trying to push on us, with the help of Al Qaeda, really.

AS: And Sean Hannity.

AR: Yeah, all those people. So, finally, then if that’s the case, if it’s a new world picture, what does it mean for psychedelia? Now, I’m not really sure because it depends on whether or not people let Obama do all their dreaming for them, or not.

So, that said, I don’t think we’re somebody who can become a culture of adults again, even though Obama is much more of an adult than we’ve had in… I think the last adult president in my opinion was Jimmy Carter. Well, no, George H.W. Bush was an adult, he was just, a creep, I think, but he was an adult. Reagan was post-adult.

AS: Post-adult. What is that, geriatric? Or, on another plane?

AR: Yeah, he was on another plane. Hopefully our emotional span will be short enough that, when we get over Obama, we get into ourselves, in a good way. We get into ourselves as people that can do things. That we can be people that assert, people that actually own their own, I mean this is sort of corny but people that actually own their own dreams, own their own imaginations, and recognize that they have agency in their own lives. There is an element in the Obama rhetoric that suggests that he will be asking that of the public, and I certainly hope he does. I don’t think Obama will turn into a tyrant or something, but, most of the sort of accusations of a cult of personality against him I think are the accusations against someone being popular, but whatever that can become, it could happen to anybody. I don’t think it will happen with him but, but if anything, we could just become very complacent.

Now for contemporary art and music culture and all that kind of stuff? I know for me, it’s not as if hope will completely replace the feeling of dread in the world. I think it’s very nice to have sort of a sliver of hope about our political lives, but the dread’s still there. The future still doesn’t look particularly bright to me, I have to say, which I think is important. I hope that everybody else should feel that way, hopeful, except for the artists. It’s a challenge for us to imagine, to keep looking for, as always, those cracks, and the dread. It’s not as if our job now is to make sun-shiney positive art about our culture or something, that would be horrible, but hopefully…

Obama was running against a sort of self-hating sort of charisma that ran under the surface of this country for the last 30 years, that was ready to pull us all over the chasm. I think that’s what the Bush thing is. It’s this weird thing, the idea that he supposedly loves America, but, and I think this is sort of a mean thing to say, but I think the part of America he probably loved the most was the part that let him get wasted in his living room drinking Coors for 30 years. He loved the abyss. And he loves his ranch, and he loves his family. He loves a speck of the universe. I think he loves that much dearly.

I was just at the George H.W. Bush Library last week, in Texas, in College Station. I think that he and Clinton were sort of the high points of the decadence of that cultural moment, I guess Reagan through Clinton. That was sort of the apex of that scene. And George W. Bush is the obvious buffoon. You know, the fall guy, or whatever, the guy who sort of finally takes it over the edge. But I hope with all those guys, I haven’t been to the Clinton Library, but now I want to go there after seeing the Bush Library. I hope it’s as shallow and as stupidly positive as the George H.W. museum is, because, I think people, this is my optimism, I think people are going to be a lot smarter and they’re just going to laugh, like I did, at the George H.W. museum.

I mean the whole idea of Bill Clinton, you know, in retrospect it seems insane that he does not go along with our idea of what the 1960’s was, or someone who would be a product of the 1960’s, right? Truly, the president who was a product of the 1960’s was Jimmy Carter, and America rejected him right away. He was the one product of the 1960’s, and frankly he was the best. If you like a Barack Obama, just get a time-traveling machine and help support Jimmy Carter, and we could have gotten out of much of this shit, you know, nearly 30 years ago. But, in my opinion he’s the sort of figure who relates to psychedelic politics, the guy who was doing goofy stuff. He’s the guy who, he probably was friends with Carl Sagan, because imagine having Carl Sagan over for dinner or something, right? And they wouldn’t get bored of each other, that kind of thing. But Bill Clinton, he’s sort of the equivalent of bad New Age music.

I think what’s kind of exciting about this time period is that, in a good way, it’s hard to imagine the future again. We actually are in some new territory. People saw the future with McCain, and it’s not like he was evil or something, but people saw the future as not dissimilar from what we’re currently in. And, in some ways, we chose the unknown. I think a lot of the criticism of Obama is truly, “I’m not entirely sure what he stands for.” In a lot of ways, I’m not really clear on what a lot of his plans are. I was only sort of engaged in the campaign on that level. I was much more interested in the mythic aspect of the campaign, the battle of charismas. Or really the battle of charismas was kind of like, it wasn’t Obama vs. McCain, it was Obama vs. a generation of thought about who America was. It was against the mythic self of America of the last generation.

Born to Live Life, 23:10, Super 8 on video, 2005

Originally from Dubuque, IA, Andy Roche currently lives in works in Chicago. Roche works in diverse media showing both in gallery and screening settings, primarily in Chicago. In 2008 Gallery 400 at UIC hosted a solo show of his work. In June of 2012, Roots and Culture Gallery will host a solo exhibition of his work. His band Black Vatican released the album Oceanic Feelin’ on Locust Music in 2011.

Alexander Stewart lives in Chicago, Illinois. Born in Mobile, Alabama, he graduated from the University of Richmond, and received his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Alexander teaches in the School of Cinema and Interactive Media at DePaul University, and programs a monthly screening series at Roots & Culture gallery.