Clare Wilkinson

All images courtesy Anthea Mallinson.

A critical pre-production function in contemporary drama, fantasy and historical films is the deliberate, and deliberative, aging and breakdown of costumes. The special category of breakdown artists who perform this task often come from backgrounds such as textile arts, and bring to bear on their work a sensibility that responds both to the stories contained within the objects they produce, and the characteristic ways in which materials react to certain kinds of handling. For the past few years, Anthea Mallinson, a textile artist, teacher and professional breakdown artist for the film and television industry, and Clare Wilkinson, an anthropologist working on the culture of craft and media production in India, have been trying to elicit the larger philosophical and experiential lessons that emerge from paying close attention to aged costumes in film.

Clare Wilkinson: We have been talking for a while now about the work of craftspeople in film as a specifically aesthetic practice. It is unfortunate, but I wonder if calling the work craft demotes it to the purely utilitarian—opposed to the creative activities of the director, actors and so on. An experiment one might try in response to this would be to lift, for example, the distressed costume out of the narrative context to which it belongs and which it informs, and to see the result for the maker and for the viewer. How would the maker talk about the object? How would the viewer look at it?

Anthea Mallinson: The division of the mind from the hand, the theorist from the maker, the dominance of the ‘idea’ or ‘content’ as divorced from material production is at work in the general absence of the craftsperson from theoretical consideration of filmic cultural production. I think that many craftspeople in film production wear the label ‘craft’ proudly. However, outside of that community, the work of the craftsperson in film is almost invisible. Sometimes, of course, its intention is to be invisible, as part of the illusion of reality and verisimilitude that is so important to Western film production. To achieve complete invisibility is something the film artisan strives for. Consequently, it is very interesting to consider lifting the craftwork, in this case the distressed costume, out of the narrative context to which it belongs. In this way, the work becomes visible on its own for the first time.

The maker, creating a garment within a narrative context, uses narrative as a primary inspiration. However, their narrative is not just the story of the protagonist or antagonist in question; it is also the material’s narrative—the material’s mutation and disintegration in response to time and events. Film craftspeople are exquisitely skilled makers, responsive to and inventive with a wide material vocabulary. In my experience, ‘making as thinking’ is present with force in this community. But I am certain, in answer to your question above, that the maker would expect the object, the costume, to continue speaking with a narrative voice.

Army Artefact (studio view), 2013, Leather objects, metal and canvas helmets, texture added, acrylic paint, leather oils.

Aoife Monk, in the 2010 publication The Actor in Costume, has written, and I agree with her, that the costume is generally understood and received as essentially indistinguishable from the actor. She notes that ‘when a costumed actor appears onstage, it is often very difficult to tell where the costume leaves off and the actor begins. When we speak of costume, we are often actually talking about actors; and when we speak of actors, we are often actually talking about costume’.[1] This lack of division between the two is especially fluid as it is usually unconscious. A costume should not be visible enough to interrupt a narrative; in some sense it is meant to disappear.

Based on my experience as a breakdown artist, head of crew and teacher, I feel the costume breakdown artist grasps this intuitively without articulating it, perhaps without needing to articulate it. In the process of creating the broken-down garment it will not have occurred to us to consider the display of the garment outside of the narrative context. Nonetheless, the creative journey of building (through destruction) the narrative content of the garment occurs with the character in mind. This is done, incidentally, without the actor being present. The designer considers the physicality of the actor, their desires and their working method, and selectively translates this to the breakdown artist. The breakdown artist then concerns themselves with the physical specifics of the actor as they intersects with the narrative of the character.

Regarding the viewer, their ‘reading’ of the object would vary widely depending on the context of its presentation. If a broken-down garment is presented as part of the history of a specific film, or the garment of a star, the narrative would dominate. However, we are all familiar with the legitimacy and value given to a partially disintegrated costume in the museum context. Lifting the garment off the actor and outside of the film production, but not placing it within the familiar context of the museum (our agreed-upon location for legitimizing objects on the way to ruin) would be an interesting experiment. Certainly the work of the film craftsperson would become visible in its own right.

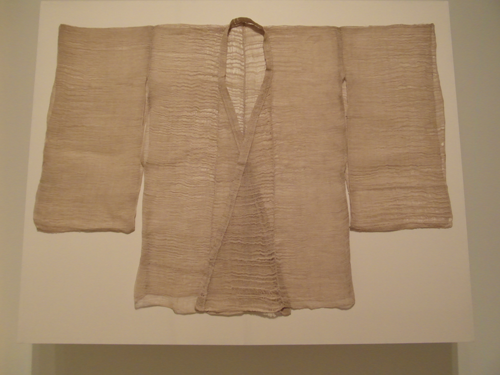

For example, in the case of the Yore Mizugoromo Coat, created in the 18th century for the Noh Theater and presented in this century as a specific item in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, the museum visitor meets the garment on its own. The work of the craftsperson speaks, supported by the museum descriptive:

This ragged coat, with its utilitarian material, very open plain weave, and displaced wefts, appears to have had a hard life, perhaps as a worker’s garment. However, the coat, known as a yore mizugoromo, was only used in the theater, where it was worn by actors representing the poor and destitute, old women and ghosts. Wefts were displaced deliberately to create the appearance of heavy wear.[2]

The costume designer, theatre director, actor and specific narrative are gone; the hand of the craftsperson is present.

Overcoat for the Noh Theater (Edo Period, 18th century, Japan), Hemp, plain weave with areas of displaced weft. James D. Tigerman Estate, Art Institute of Chicago.

Dark Armour Skirt (studio view), 2013, Vinyl, hard plastic, acrylic paints, acrylic texture mediums.

CW: To age a costume is to introduce time into it. And time means, in this case, events, experiences, traumas and so on. The aged costume entails a presumption of action in the character, actions we may never actually see. In imagining and recreating the tangible and visual results of these actions, could we see the breakdown artist as a kind of performer?

AM: There are techniques, tools and mediums contributing to the breakdown artist’s aesthetic vocabulary, and the ever-present problem-solving skill base of the craftsperson/artisan, but the crux of the work is definitely grounded in imagining a character, a life and the actions of that life. How has the character built their life over time, and what marks are made by current events?

Our conversations and some of your analyses of communications between crew members on Bollywood films helped me perceive the amount of creative negotiation that occurs amongst the costume team to determine the specifics and the subtleties of choices made by the craftsperson in building character through costume ageing and breakdown. If a middle-aged white-collar man doesn’t care about his clothes and hates shopping but was raised a Roman Catholic, what do his shoes look like? If someone had the plague, was burned in a boat fire, lay on the bottom of the sea for a hundred years and is a good guy, what do they look like? What do homeless people really wear and is it dirty? Or, to take an example from a film that is a half-century old, how is the character of Joey Doyle (Ben Wagner) in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) manifested in his jacket, and what is the significance of Terry Malloy’s (Marlon Brando) choice to wear that jacket? The creative evolution of such a garment must be imagined—it is complex and needs to be carefully negotiated.

In the case of Joey Doyle’s jacket, Joey is deceased, and the jacket itself carries his character forward. The breakdown artist would need to imagine Joey rather than the character Terry, who wears the garment. Similarly, a character might don a parent’s or grandparent’s jacket, scarf or boot. In this way, a garment that wears the marks of a life lived can speak across time into the present.

New Boot (studio view), 2013, New leather boot, texture added, acrylic paints, waxes.

Then there is also the narrative of the world surrounding a given character—is the world a dry and dusty desert or a mould-inducing rain forest? If one is on another planet, what color is the dirt? The breakdown artist may also strive to construct a life story not of the garment, but of the specific fabric they are working with—what does linen, burlap, silk or wool do over time? How does polyester burn? What remains of old velvet as opposed to plain weave cotton? Thus the aged costume entails a presumption of action in and beyond the character.

Sometimes within the genres of fantasy or space, fantastic spans of time are depicted, such as the space warrior who has been trapped floating through the universe for several thousand years, and whose armour must reflect this journey. Another breakdown narrative that goes beyond the individual is a scavenging scenario where some series of disasters has destroyed the manufacturing sector and depleted supplies of all kinds, and the character must scavenge to clothe themselves in remnants, bits of packaging or bits of armour. (Some of these scavenged costumes can be seen in Waterworld [1995], The Chronicles of Riddick [2004], and more.) These costumes can become fantastic and sculptural, displaying both the dilemmas and the inventiveness of the fictional wearer.

However, much as they are engaged with imagining both the physical and emotional aspects of performance, and their decisions may demonstrate the craftsperson’s participation in authorship, I don’t think the breakdown artist is themselves a performer.

Corroding Armour Creation (studio view), 2014, Vegitan leather, silk screen, texture medium, speciality acrylic paints.

CW: There is, as we know, a discourse about how the aged costume is beautiful, paradoxically so since it imitates something that has lost its pristine beauty. What is termed an ‘organic’ look, a look that references the fact of change, loss and erosion in the world, is imbued with value. But there isn’t universal agreement about how ‘organic’ something needs to look—when a piece has been aged too much, or even too little. In discussions of the ‘real’, designers, breakdown artists and others have to find ways to reconcile the demands of the story with how the aged costume actually looks.

AM: As you and I have often discussed, there is a heavy emphasis on making it ‘real’ that is embedded in the language the costume designer uses to direct her breakdown artist or ager/dyer: ‘it can’t look off-the-rack’, ‘take the newness off’, are standard requests from a costume designer to the costume crew. But, of course, a definition of ‘real’ has to be negotiated and defined by the costume designer, production designer, director, producer, actor—and interpreted by the breakdown artist. It also has to satisfy the contemporary audience’s understanding. As a costume designer once commented to me, ‘Every fan is an expert on what Superman looks like’. Certainly, there are cultural rules around the ‘real’ behaviour and appearance of ghosts, zombies, vampires and the like.

Technological demands sometimes restrict visual options. While technological limitations have always existed, at present these restrictions change frequently with developments in equipment. Therefore, even though a character might well wear a busy plaid, or a clean, white shirt, the camera might demand that he does not. And sometimes the ‘real’ is compromised when there are demands that a movie star must look like a star to fulfill the wishes of their audience and fan base. At these points, a different set of visual imperatives push themselves to the forefront, but these are always intended to be completely invisible to the audience and undisruptive to the narrative.

In my experience, the narrative of a film production has a highly developed back story which is in place in order to help the team make aesthetic and visual decisions that will inform the building of the narrative and support its believability. Believability, in this culture, is deeply attached to concepts of action and effect within sequential events and the narrative of time. Cause and effect are manifested in and made apparent through the physical plane, and the careful tracking of continuity. The highly developed back story, or ‘history’ of a given fiction, will supply the information the film craftsperson needs to make visual decisions, from the number of suns a world has to the color of the dust.

Overcoat (studio view), 2013, Linen overcoat, texture added, acrylic paint, waxes.

[1] Aoife Monks. The Actor In Costume (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), 11.

[2] Museum label for Overcoat for the Noh Theater, Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago.

Trained in Europe as a tapestry weaver and dyer, Anthea Mallinson has worked as a key dyer, breakdown artist and textile artist in the Vancouver film industry since 1997. She teaches at Capilano University in the Textile Arts Department, a position held since 1988 and in the Costuming for Stage and Screen Department since its inception in 2001. Her numerous film credits demonstrate a wide and versatile range of creative textiles specialties. For the first ten years of her film career, Mallinson worked on single productions; for the last several years she has been working on specific pieces for numerous shows at a time. Mallinson balances her love of teaching with her active film career.

Clare Wilkinson received a PhD in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania for her study of the culture and aesthetics of an embroidery industry in Northern India. Since then, her work has focused on art, craft and media production, with a particular focus on costume design in the Hindi film industry of Mumbai. Alongside numerous articles and essays, she is the author of Fashioning Bollywood: The Meaning and Making of Hindi Film Costume. She is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Washington State University, Vancouver.