Gregory Minissale

All images by and courtesy the artist.

Steve Lovett is an artist and educator working in print education and research at Elam, University of Auckland. His work is archiving images and stories. In these photo-based collages and prints, Lovett is concerned with exploring social, historical representations of queerness and memory. Lovett redeploys historical ephemera from queer subcultures and family narratives to examine loss, ecstasy, and humour, the forces that shape us. These works are selected from his ongoing drawing practice, where Lovett constructs collages, digital prints, and silkscreened paintings.

Make it new, 2020. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage ink printed on metal 6 colours. 630mm x 430mm.

Gregory Minissale: Were there any gay artists who were influential for your practice?

Steve Lovett: suppose these two in particular, whose work I have paid a tip close attention to, over the years. One David Wojnarowicz and the other is Derek Jarman, both because of the way that they construct narratives in their work, and frame questions about how we come out, how we venture into the world, how we navigate spaces for ourselves, that aspect of storytelling is of huge importance to me. But then if I think about it, and I go back even further, then there is John Heartfield.

GM: Ah, you mean the montage, the radical side of his work?

SL: Yes, his indication that photomontage could be a weapon. Rather than just doing this surrealist thing putting together of unlike things, it’s the strange bodies and odd situations that reveal there’s a critique going on. Yeah, it’s always really important to me to think about that critique. I mean, I think it has a lot to do with where I come from, how I grew up, how I kind of ventured into education. I think about things being contestable all the time.

GM: And I find it really interesting that what you’ve mentioned is that lots of ideas are clustered around the body out of place or time, and perhaps kind of angry and annoyed that I feel that I’m unwelcome constantly, and these feelings are reflected in your work?

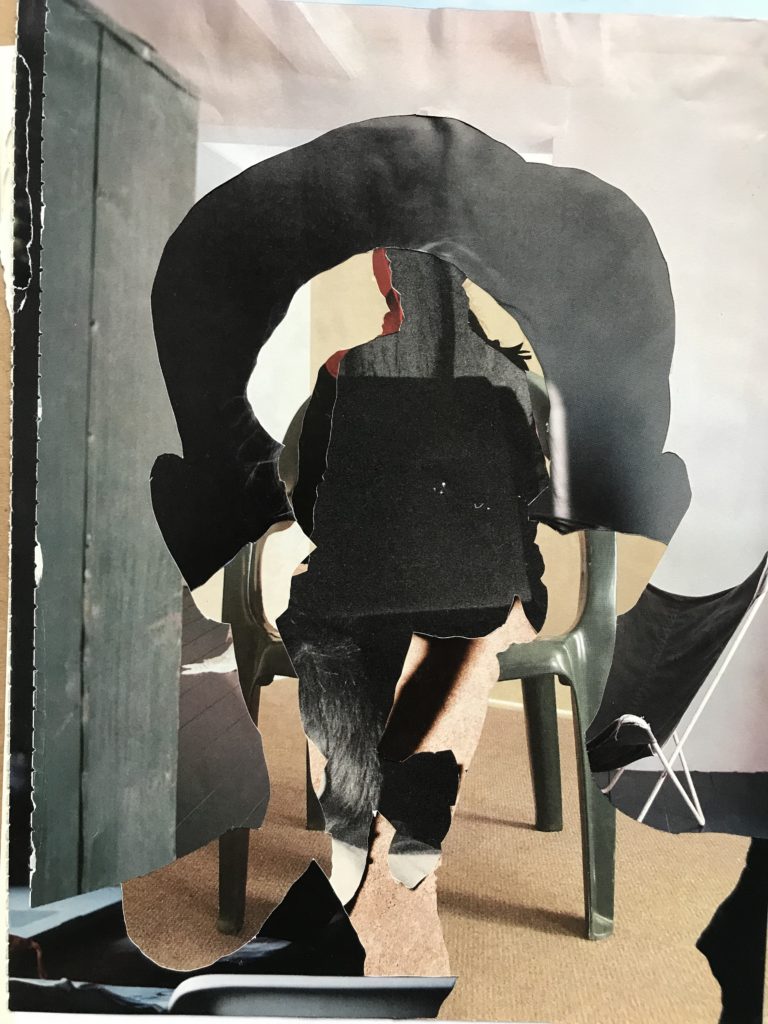

Sitting in Studio, 2021. Photographic auto portraits, hand-cut analogue collage, digital assembly. 300mm x 250mm.

SL: Yes, totally. And this is where the idea of “wagging” is relevant. Wagging is New Zealand slang that I grew up with. You’d wag off school, like skive off, would be the English equivalent. Yeah, and you would wear your scar. Now, you might want to do something like wagg off just because you wanted to go off and do something, you know. But the other reason, which I kind of like, is that I don’t fit in here and made not to fit here. And if I do it, even now, it gives me a sense of agency, an agency that I often feel is denied to me.

GM: I was reading the other day that Michel de Certeau calls this wearing a wig. So you put your wig on to pretend that you’re a really good employee but actually, you’re writing poetry or painting a picture and not doing something which is on the conveyor belt in terms of capitalist production or corporate ideology…breaking off a little bit of your own creativity time, whatever because you’re not allowed to be creative in the way that you want to be creative in normal everyday life.

SL: And so this is constantly this thing about subverting the roles that have been ascribed to us what’s presented to us, so there’s this constant kind of evasion of discipline.

GM: So that keys in quite nicely with facture then because in terms of not only spending the time to do this but also in the way in which collage/montage is seen as a disruption of the ‘normal’ spaces of art and life, and you are meant to do. So basically, against traditional notions of art as beautiful, you rip it up, tear it up and remake it in the way that you want to remake it. Things that are really important to you?

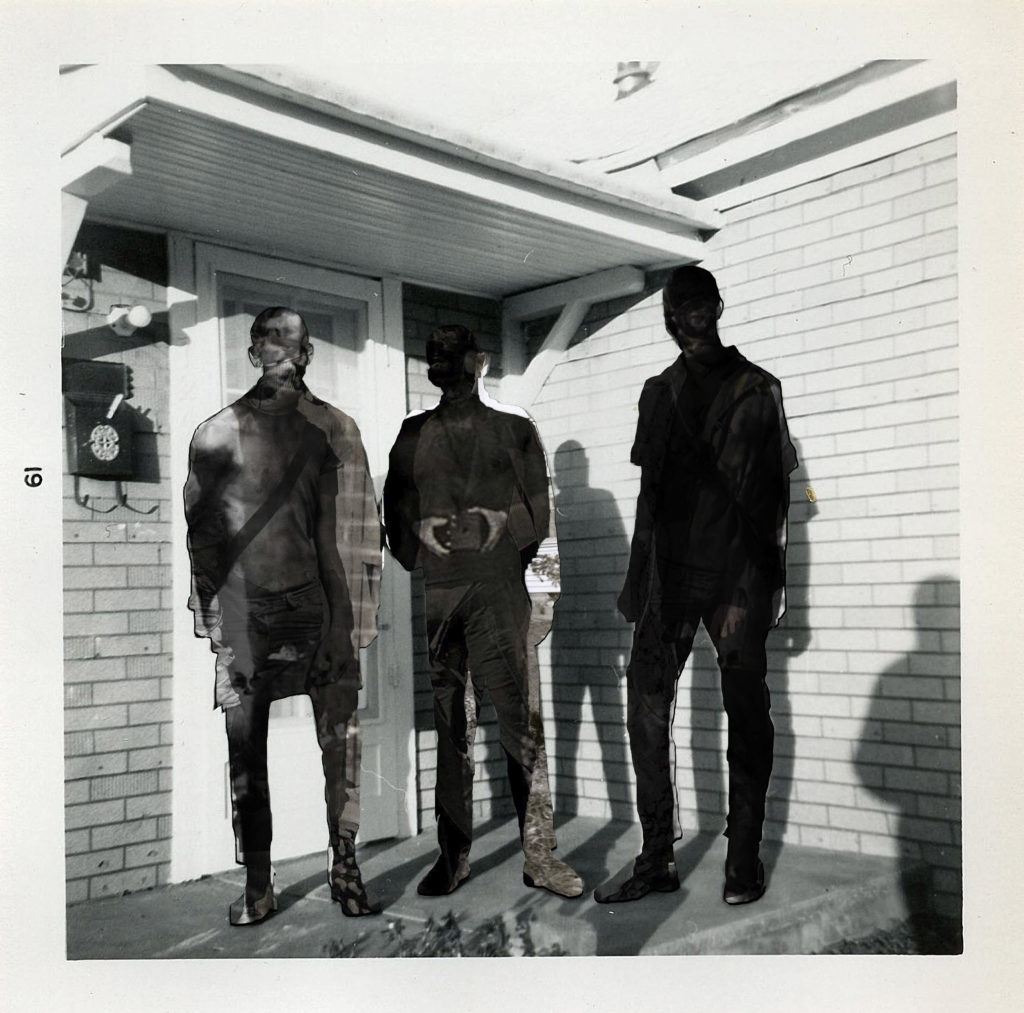

Imperfect recall, 2020. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage ink printed on paper 5 colours. 630 mm x 430mm.

SL: And it’s that sense of cutting things up to take these pieces out that are useful: because there’s so much which isn’t useful. And I think that Heartfield or somebody like Boltanski, you know because I remember seeing the newspapers that he’d flattened out and saw these contrasting stories side by side. It’s that whole process of cutting things up and taking them apart. It’s like wrecking something to see how it works. Because when we think about the way that it works in a really direct way, we often miss the construction that’s out of view.

GM: So, do you feel that your facture is a way of bringing that into view?

SL: Yeah, well, that’s the intention. I remember the first time I did it consciously. It was before I’d seen the Boltanski stuff. It was in the 90s when we had a National government, and there was the Prime Minister’s family who were graduating from university on the front page of the paper, and everybody was applauding and saying “how nice”, and this was separated by just two centimetres of newsprint. And you just needed to flatten that paper out to see this extreme contrast. And if I go back into personal history, you know, I grew up in the centre of town, in the 60s, and it was a very Māori Pasifika neighbourhood, working class. And that was just the way the world was. Lots of people went to school barefoot, I did, and English wasn’t necessarily the first language for everybody in the class. Being at school was like negotiating crowd control. And then I went to live on the north shore near my grandparents when they were quite elderly. I went to a different school, a very white school, and we literally went only seven kilometres to a different location in the city. And there was a completely different culture, a completely different way of going to school. And it was really shocking. I never adjusted to living on the north shore for that reason. There’s nothing bad about the North Shore. It’s quite a nice place, but it was the changing culture that at 14 the contrasts were shocking.

GM: I can see how, when I look at your work that, all of this kind of makes sense, and that it’s not just about things being out of place, but it’s also about boundaries, and how they’re forced into the world that we live in and then, you know, some if some of us cross that boundary then it’s transgressive, it has consequences, everything’s territorial. Do you do you ever feel that your work is dealing with not just presences and absences but also to do with these kinds of spatial concepts?

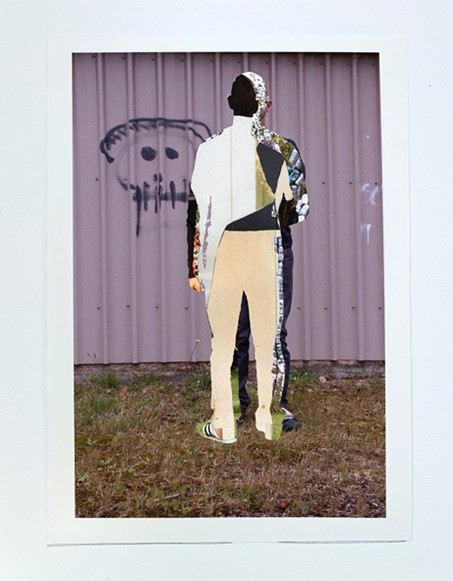

Sit and Wait (Out of Fashion), 2019. Found photographs, magazine images, hand-cut analogue collage. 300mm x 250mm.

SL: If you come to the house again one time, I’ll point out some work to you. Two different bodies of work: one made around the time of the Foreshore and Seabed Act (2004), [this was the Crown seizing Māori land] Partly in response I spent a summer trespassing. I would trespass onto pieces of land that had been recently expropriated gone into private ownership and would record a few hours of time pass. There was silence about the money that flowed into this country in the early 2000s, after 9/11, lots of people came down here; lots of wealthy people came here from America and Europe, and they wanted a bolthole, and they were able to buy very expensive pieces of land. And so, there were pieces of, of the coast, of land that could no longer be accessed because the new owners made access difficult or impossible. so it was all fenced off and couldn’t go there. There were large parts of the countryside that became privatized quietly.

GM: How did that feed into your work?

SL: I think about about space and the rules that govern these spaces. Lee Wallace has written about this from a sociological perspective identifying who make rule, who is compelled to follow them. This was in my head as crept onto privatized land to take photographs. I became very interested in the different uses of space in the city—the skateboarders that would come out after work, office workers, who would kind of transform a square and other public place in the city. Interested in the different economies, different cultural uses operating on the same ground, overlapping one another, often not intersecting. Place in places like weekend markets, cruising sites, temporary occupations of commercial spaces in the city, and other venues; people who operated out of view of the corporate system and stuff, as much as they could or had to. I found this layering of the city I have lived in all my life interesting. For a couple of hours, there would be an alternative economy that would come into view, and then it would disappear again. It’s fantastic because it completely goes against the way that everything is increasingly corporatized.

GM: That’s why we’ve got your little vegetable patch on the street here, outside your house. But tell me, how does that fit into your practice, is there a way in which that spatial awareness that you mentioned becomes the spatial awareness in your imagery?

Devour, 2016 – 2020. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue de-collage. 300mm x 250mm.

SL: It is connected to an awareness of and a consideration of operating in spaces that have a slight or extreme criminal potential to them, you are suddenly out of view, and you can do things: “I can do that.” Sometimes it’s illegal, plainly illegal. You know, I mean, there’s that potential. And sometimes I’m able to pour that into artwork, sometimes not. It just doesn’t happen because it’s too loose a quality to anchor on paper or some other surface.

GM: So are you saying that it’s kind of intuitive and implicit rather than explicit approach? But also, it’s not as if you just sit down and scribble something, you work involves quite a labored, technical process that readers won’t be familiar with. Could you just give a summary of how some of the images that we’re publishing emerge, what the backstory is in terms of how you make them?

SL: Okay, so at the moment, the thing that I’m really interested in is working out of Gamut. Gamut is a rule or a strategy, or a line of logic, to follow an argument. And so, RGB [the constraints of the red, green, and blue color reproduction system] digital or analog is a color space with disciplinary rules. And also anything that involves a metallic quality or effect that is outside that RGB color space. It’s also ‘outside’ in the way we see a lot of printed information. So, by employing those two strategies, I get something that isn’t constrained by those two big disciplinary imaging systems.

GM: Right. So is it the case, then, that you’re subverting rules and methods and hijacking or subverting like a Trojan horse disciplinary techniques and logical printing technologies?

SL: Hijacking is a good way of putting it. It’s, it’s playful, giving the finger to commercially engineered image systems. If you go down and if you make digital images, you are disciplined the whole way. From the time you cache up or create the image to the time it’s printed, you have to go down that trail. The printer won’t handle the image that doesn’t print properly, or it doesn’t appear as it did on screen. It is possible to control a color space using inks in that kind of way, and you can make any number of colors, but they are within interdisciplinary space.

GM: So you’re able to subvert the rule-based system from within, and add something which then it becomes more variable, is that right?

Bodies At Stake (In the city), 2019. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage ink on metal 6 colours. 500mm x 860mm.

SL: Yes. Infect and inflect. And so to give you an example. The thing that I finished making at the weekend was printed directly onto metal. The image began as a paper collage, and then a series of photographs and so on. I wanted to have something more resilient than paper. So, I could print on board that I am kind of interested in printing on metal because, especially a non-ferrous or corrosive metal like aluminium, it’s very stable. And when I kind of lay down the inks on there, and I mimic a photogravure style of printing, like potato chip bags; I put down white first of all that into the metal, or I copy it onto the metal, and then I lay the metallic inks down and then print over the top of that. I get something that no digital printer will make, that no commercial process will make as easily because of the range of things I am building into it. And it is this building something with the potential to tell a story, which is a shard or a fragment of something off to one side, and something that is often overlooked comes into view, and that’s really important too.

GM: Nominally, they are prints, but they are kind of monoprints, isn’t that another way of subverting the whole aesthetic of printmaking…

SL: The thing about printed imagery that interests me from the get-go is its ability to tell stories and to transmit images over distances. The thing that most printmakers become obsessed with is making multiples and series, and all that kind of stuff is the most boring thing in the world, repetition…

GM: This is why you’re very different from Andy Warhol.

SL: Oh yeah, absolutely. He was a great businessman, and I could probably learn from his business model. But I’m more interested in that notion of telling the story and making sure that that story carries with it some potential to express or argue a point, rather than being this commodity that fits into an economic system.

Getting ready to go hunting, 2016 – 2019. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage ink on metal 6 colours. 500mm x 860mm.

GM: Yes, I appreciate that, and I think that, that there is an economic system which is a rules-based one, but you’re abusing it deliberately so that you can be free or be creative and spontaneous

SL: I mean Boy George, when he was in one of those career slumps, said there was nothing more punk than giving work away, so there’s lots of work that I posted online for that very reason. The work travels out into the world beyond my control and ends up in all kinds of strange places because it’s on the internet. Rosemary MacLeod, in a book about craft, Thrift and Fantasy, talks about a gifting economy. That subverts our normal understanding of an economy. It happens in private spaces. It happens away from the scrutiny of economic control. And I think this also meshes with what Thomas Waugh says in Hard to Imagine about the private uses of photography from the moment the box brownie appeared, about the co-opting and corruption of technology for other and often illicit purposes.

GM: And you are taking something the world of images out there and repurposing it, or they are the image of what you have photographed.

SL: I vacuum up images, you know, and I collect things. Like Richter, I have this big collection of images. Even from the moment, I was aware of popular music having, you know, 12-inch artwork on those albums. I was very aware of imagery. I suppose it’s from watching television and being saturated by all that stuff growing up and how that feeds my sense of how visual the world is. And I can think of some truly horrid images from childhood news footage, Vietnam. But also going to second hand book shops, buying up old porn, old Life magazines, and stuff, those things become triggers to do work, restage work, etc.

Last light, 2017. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage. 150mm x 150mm.

GM: I think most people will see that there’s an identifiable, what people used to call, style at least in the images that I’ve seen, or constants: like there’s an environment, a room, or there may be a bit of an urban scene a street or a bridge or something, and then somebody seems to be there, but they’re cut out of that continuum, and then within the cut-out, there seem to be other objects placed inside of the figure, as well. Why is that a consistent aspect of facture in your work?

SL: It emerged after I destroyed a whole lot of work. I became very frustrated with some my work, and I burnt stuff, cut holes into stuff. And I had this this pile of rubbish in the studio, and I’m looking down at these, but I didn’t see it immediately. I went on a couple of residences in Australia. And I was in this place in Tasmania. And it’s interesting that in the southern hemisphere how we settlers have organised our history. I saw this interchangeable roster of place names everywhere. It was very disorienting driving through some of these places because it’s like somebody’s reshuffled places, and the names are in the wrong order, they’re all very familiar to me but disordered. And so, I arrive in this little town called Queenstown, near the west coast of Tasmania, a mining town, and I’m photographing stuff, and, looking at this street. It’s the ruttiest street, with broken down cars and houses, and it’s got my family on it. That, in particular, made me aware of how transitory things are. We’re here and not here at the same time. And just, you know, like the news this morning about the environment, it’s not like these things are endlessly transposable; that one idea fits a whole lot of different contexts, but I think how fragile existence is. You know, I mean, a town gets washed away in Germany. The west of the United States is on fire.

GM: So is your work then, a way of dealing with that.

SL: Sort of. I often see making work as a way of metabolizing the world around me, metabolizing my experiences. Forty years of climate action have led to nothing. We produce more C02 than ever. We remain desperate to consume non-renewable energy sources. We learn nothing, there’s 7 billion of us, and soon there’ll be 9 billion of us. We’ll change tomorrow. Sometimes when I remove these figures—and I have boxes at these kinds of figures that are just kind of like in some kind of mass grave—I think that’s where our future is. A bit depressing, really, but it’s that constant since we think we’re here and we think we’re permanent and we think we’re kind of really solid and corporate and everything, and we are not.

GM: That really adds a lot of bite to your images in terms of ambiguous presences. Whatever you think is lasting is actually ephemeral, and whatever you think is a fact is actually manufactured. And then all of these things to do with creativity and whether it can amount to anything…

Last One (Clean Cut), 2014 – Printed 2020. Found and made photographs, magazine images, hand-cut analogue collage screen Print, 5 colours on paper. 630mm x 450mm.

SL: Totally. It’s kind of like when I think about the beginning, like starting a job and or what’s in Wojnarowicz, Jarman, and Heartfield, for instance, all this work has a bite. If you’ve ever sat in the theatre and watched Blue and being bathed in that blue light, you know, Jarman talks about his friends, phoning up and making weird phone calls to him as you’re going crazy with toxins in their brains. I mean, it’s stabbing. If you’ve lived through that stabbing, if you’ve had the same conversations with people, it’s brutal. You know, and I mean, I don’t know whether Patrick Kelleher is a gay man, but you know you watch London and Robinson and space. You know those long kind of static shots of things that are seemingly innocuous until you listen to the narrative and how he peels back the layers on those things. You get a sense of just the complexity of modern life in relationship to historical precedents. And those things made a huge impression on me when I saw them for the first time. It’s that we might, you know, think that there’s something lovely or funny about something, but then you peel back that surface. So, you take the figure out of that image, and behind it is the history that produced that person.

When I viewed the Giotto work in the Scrovegni Chapel, there was this really beautiful moment after you’ve walked in and looked at everything and burst into tears. And when you walk out and look up, and there’s the tissue of the world folded back on itself. It’s extraordinary for me, you know, I’m not religious at all. But it’s this incredible moment in image-making where what we think we see is really solid was presented as solid, whether it’s beauty or ugliness or its desolation or something. Then it peels back, and there’s something behind it, and if we waited long enough, maybe there would be something behind that as well.

DILF from Delft, 2019. Found and captured photographs, hand-cut analogue collage ink printed on paper 5 colours. 630mm x 430mm.

GM: I see all of that active in your work, the veils, the layers to it, the layers of factor. But I also see, not just a question of loss, as in the Boltanski, but understanding the idea that it could be layers of the Scrovegni Chapel folding in on itself, this is a lot more optimistic and uplifting, isn’t it?

SL: Well yeah, and because I think you know we’ve just gone on this kind of downer…But the thing about wagging. Wagging is about agency…doing something completely, you know, under the radar. Something that I might be able to do, you might be able to do, create something that we couldn’t anticipate that might be marvellous.

GM: Well, I’m gonna definitely have wagging as part of my general vocabulary, now. Thank you for that. I think we’ll leave it there. Okay, that’s a great interview. Thank you very much.

Steve Lovett (he/him) is a practicing artist and art educator who has taught print for 3 decades at Manukau Institute of Technology Faculty of Creative Arts, and more recently Elam Te Waka Tūhura at the University of Auckland, Tamaki Mākaurau.

Through diverse range of art practices from sound archives to collaborative community projects and, in on-going studio projects Steve has long-standing engagement with the LGBTQIAPOC communities. One focus of Lovett’s studio practice examines the interface between digital processing and the stabilizing digital ephemera with inked images, one of the foundations of archival records. His work has been shown nationally, through-out Aōtearōa and internationally. His work is held in public and private collections in Aōtearōa (NZ), Europe, China and North America.

Gregory Minissale is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Auckland and is the author of Rhythm in Art, Psychology and New Materialism (Cambridge University Press, 2021) and The Psychology of Contemporary Art (Cambridge University Press, 2013).