Greg Minissale: What does ‘dirt’ mean to you?

Carli Holcomb: When I think of dirt, I can’t help but think of digging. Of pushing my hands deep in the fragments of the earth. Micro landscapes from centuries ago, caught in the peripheral, clinging to our clothes, catching in our eyes, and collecting in our homes. Dirt feels like a witness. A claim that is broad, and forgetful of consciousness, but for nearly five billion years, if not more, dirt has been watching as the boundless mystery of our world, and those like it unfold.

GM: Could you tell us what materials you are drawn to and the specific techniques you adopted for Once More, Unknowable Terrain and Amalgamate?

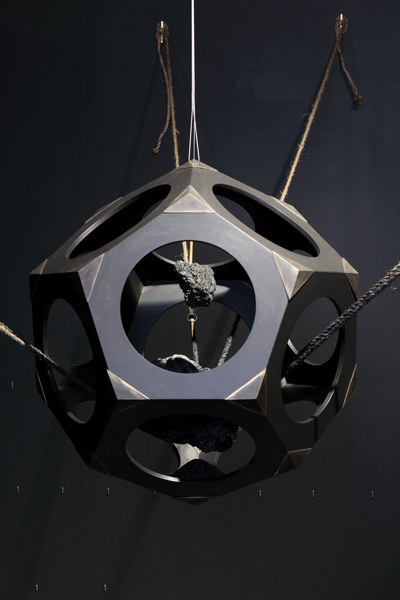

CH: I have always believed places sink into us. Out of respect, I let the sites I am working in guide the materials I use. By pairing opulent surfaces with tokens of the landscape, I allow materials whose sources originate in nature to sit side by side with materials that exist because of human design. In Unknowable terrain I used materials I consider directly enlivened by the cosmos, metals like silver and gold that are formed during the core collapse of supernovae. These material origins enable a perceptual shift between cosmic and human scales, and create a dialogue about the fundamental ethos of space. I have to acknowledge, that with the multitude of materials artists have access to at this time, and of the nearly infinite options, I have chosen to work with or replicate the very substance of the earth.

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

Amalgamate is nearly entirely composed of materials derived from human intervention. Plexiglass, resin, chandelier crystals, foam, refined metal, and trash are tightly sedimented into layer after layer. These artificial materials were then coated in dirt collected from the space it was photographed in. Allowing Amalgamate to be of the space as well as in the space. Amalgamate’s “environment” is a colossal structure dating back to 1883. It stands today as a fallen monument of human ingenuity, and a place of incredible biodiversity. I am drawn to the exchange that exists between the natural world, and our perceived separation from that world. The building was made from materials of the landscape surrounding the space, as the rocks were quarried from that location. The building was erected, used, and forgotten, and now a new landscape is thriving within the walls. It messes with sequential time when you consider all of the narratives at play within the space.

Amalgamate, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

Once More was made out of resin with a rim of salt. The resin emulated pools of impossibly blue liquid. They emerged from my memories of glacial silted mountain streams. Once more was documented in the rain as the liquid of the environment slowly etched and dissolved the salt leaving only the artificial water untouched. The location it was photographed in was also dissolving. The tiles breaking apart into random pixelated pools were yellowing, natural forces were eroding the cement, and plants were slowly taking back their former territory. I want to understand the natural environment in as many ways possible, to create a set of relationships questioning where nature begins and ends is an avenue for me to do that.

Once More, Mixed Media, 2015.

GM: Do these artworks have a kind of ‘life cycle’ or story of their own?

CH: Everything I do feels temporary. I treat the merging of architecture and object as an act of stewardship. The spaces are temporarily adorned with the objects I place within them. For a small moment the object and the spaces’ stories are linked. This is also a way for me to connect with the environment. Giving me a means of moving through a space while it simultaneously moves through me. This movement through a space seems inverted and timeless. A moment without a clear beginning, middle, or end.

The objects like the spaces are shifting, and are constantly being changed by the phenomena of their environment. Amalgamate didn’t truly feel of the space until the object’s reflection in the water lined up perfectly with the object itself. The reflection was secondary, a separation, but it felt like it belonged most earnestly to the space. I waited hours for this alignment, and in the moment it felt absolute. A totality in some ways.

Once More, Mixed Media, 2015.

Once More reacted with the autumn rain that was falling and slowly disappeared. Once More has the most evident life cycle as it was made primarily of salt that dissolved in the space. Once More exists only in images as the object was destroyed by rain, and the site was later demolished to make way for a new building. The landscape and our cities are in a near constant process of making, and unmaking. Sites like this are a reflection of that constant change.

Unknowable Terrain is the most seemingly permanent of the three. It is made of wood, metal, and ceramic giving it a sense of material permanence. The object played host to a cycle of destruction and renewal, the internal object was crystallizing in the darkness, a process that plays out in slow time. As it is forming it is also crumbling. A mirror image of the cyclical nature of the environment. Once something returns to dirt, what comes next?

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

GM: How do you think that the photographic and digital dimension contributes to the visuality of the works?

CH: I believe all objects are not meant to be gazed upon directly. Some need to be hidden away in the forgotten parts of our world. Places like dirt that exist on the periphery. When an object is installed in a gallery there is a prescribed ritual to viewing it, Unknowable Terrain was suspended 7 feet above the ground. It loomed before you dominating the space. It’s presence in the room initiated a feeling a photograph can never replicate. Once More and Amalgamate required a context, they needed those peripheral spaces.The digital dimension gives access to a moment that enables the spaces, and the objects to possess a shared mystery. Even though much of my work exists only as documentation, I don’t feel a sense of urgency to understand why some objects need to be seen in person, and other objects need a space.

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

I think it is a question that can only be answered in the moment when an idea has yet to actualize. I generally start a project knowing where each piece belongs, and simply follow that thread. Once More is unique, because it can only ever exist as an image. In a way the least tangible means of an object existing has outlived the material of its emergence. Amalgamate was installed in a space that only seemed outwardly abandoned, yet the murky primordial soup that enveloped the water beneath the piece is indicative of life. Something exists in that water replicating, and thriving within the space. If you look closely there is moss growing on the walls where insects and birds are also nesting. I haven’t been back to the space since I documented the piece, but I’m certain the space has witnessed innumerable changes. It is strange to think that even after an image is taken, time continues to move forward, the world continues to change, and only the image remains unchanged. As we know though, even this is untrue. All things are ephemeral even the digital dimension.

GM: There seems to be a broad artistic trend that is open to letting matter ‘speak’ through artworks, and artists arrange for this space in the actual artwork, or alongside it, leaving it relatively formless. But of course, every artist comes to this point through different routes. Could you tell us if you have this special relationship to beholding matter or is it just a medium for another purpose? What does matter mean to you?

CH: I wish I could approach work by letting matter speak. Instead I think I circle around matter until I’m convinced of its reality. Every object I make is labored over, and labored over until it feels settled enough to be convincingly of the landscape. I unconsciously obey the rules of geology. My process is a constant layering of material. An accumulation of surfaces until the object becomes believably terrestrial. It is through this labor that I am able to learn from material. The layering can be exhausting, I fixate on every centimeter of my work, and continuously fail to achieve the truth of the material. Sometimes I want to zoom out of a project, and let what is be, but I am determined to push through it. To take something to the point of replication, but a replication of my own interpretation. A shift between earth-like matter, and surfaces that are decidedly unknown. It is an attempt to intricately collapse terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. To transcend a sense of separation. Through this process I indulge the complexity of matter. Deep down I think what I truly want my work to be is an extension of the landscape, something worthy of surrounding yourself with.

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

GM: Do you like the associations that someone interested in art might have with earth, entropy, decay? I was reading recently Storr’s writing in the exhibition ‘Destroy The Picture’ that suggests postwar European abstraction (where we have a lot of dirt and earth) was less interested in the clean ‘opticality’ of modernism and more interested in tactility and the abject, perhaps to do with a psychological working out of some kind of cultural memory. We seem to be revisiting troubled spaces and materials. Does any of this strike a chord with you?

CH: I do appreciate these associations. I am fascinated by the traceable lineage of all things to an evolutionary tenor. We are privileged to look back, and have the capacity to understand some of what makes us who we are. I often think of the Makapansgat Pebble, and the individual who collected it. I imagine they felt the same sense of wonderment I have felt when I’ve collected tokens from the landscape. I am familiar with this moment. The wholeness of plucking a stone from the riverbed, washing its surface, and feeling delighted to see yourself in that stone.

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

Looking back at the turmoil of postwar Europe, I believe there is an argument to be made for the individuals who witnessed to the devastation of the first two world wars, having seen something of themselves in the material of the earth. To think of the dirt and soil beneath our feet as both the giver of life, and the state of our next becoming. In a way these associations are the most honest. Everything we are, everything we will become is of the earth.

Soil is the mirror image of our society. When the materials of the earth are incorporated into art, the work becomes suffused with the history of humanity, the current cultural condition, and the deeper much more abstract history of geology which exists on an entirely different timescale than we exist on. There is an undeniable realness to it. A tactile reminder of the ability for materials collected from places, to be a part of places outside the object. It allows objects to drift, to be of a place while simultaneously elsewhere. Dirt is a carrier of meaning.

Given the current state of world affairs, it makes sense to me that artists would be looking back, asking ourselves how we got here, and how humanity allowed itself to become this? I know I certainly am. Dirt is a stabilizer. It exists beneath our feet reminding us of the tangibility of ground. It creates a place for contemplation. And still implores viewers to focus on what is real. It appeals to me in it’s ability to prove the existence of unseen territories, and to remind us that what happens on one side of the ecosystem affects the other, in the same way that what happens to one part of humanity also affects the other. We are deeply connected. When you consider the existence of soil being one of the only things that guarantees our survival you see just how connected we really are. We wouldn’t be alive without dirt.

Unknowable Terrain, Mixed Media, 2016. Photo by David Hunter Hale.

Carli Holcomb was born in 1991 in Wyoming and currently resides in Richmond Virginia. She received her BFA from the University of Wyoming in 2013 and her MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University in 2016.

Upon completing her graduate degree, Carli was an Artist-in-Residence at Quirk Hotel and Gallery, which garnered her a mention in The New York Times. Her work can be seen on the cover of the 2016 Metalsmith Magazine, Exhibition in Print, Shifting Sites. Carli’s work has been shown in multiple solo and group exhibitions. Carli has a forthcoming solo exhibition at the Visual Arts Center of Richmond, Virginia, titled After Dark. Her recent shows include PaperMakers, a group show at LIGHT Art+Design in Chapel Hill North Carolina (2017), a solo show at Quirk Hotel and Gallery, Black Moon (2016), Volume (2017) at LIGHT Art + Design, Volume (2016) at Quirk Gallery, and her solo show Unknowable Terrain (2016) at the Depot Gallery in Richmond Virginia.

Greg Minissale is an art historian with wide ranging interests in critical theory, psychology and postcolonial studies. He is author of Framing Consciousness in Art: Transcultural Perspectives (Rodopi: 2009) and The Psychology of Contemporary Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). Greg is currently senior lecturer in contemporary art and theory at the University of Auckland.