Christopher Smith

When I became aware of the appointment of AJAMU as curator for Visual AIDS 2016, I was delighted at the opportunity to interview, or rather have a conversation with, him. During the course of my doctoral research I was offered full access to a then ‘un-categorized’ archive of materials donated by AJAMU and Topher Campbell as part of the ruckus! collection housed at the London Metropolitan Archives.

My first encounter with AJAMU’s work was through my engagement with a photographic essay entitled Miss Tissue and the re-invention of the pussy tongue (that’s cock for all you unenlightened children)[1] in the anthology The Eight Technologies of Otherness edited by Sue Golding. Elated, I bought the book not certain of the journeys it would conjure.

The essay was compiled under the rubric of ‘skin’ as a technology of otherness. How did this artist see the importance of self-representation and portraiture as a means to augment the prevailing norms of representation of/by Black gay men and masculinity at the time of that work? I pondered. In the artist’s statement that accompanies the images, AJAMU makes a profound claim about notions of embodiment and the enactment of queered Black femininities and the meaning of S/M practices for Black queer individuals. Such provocations I hold onto as revolutionary.

It was a treat to have a diasporic dialogue with AJAMU on matters that we might not speak of enough, such as the relationship between HIV activism and artistic practice, but most importantly the role of the archive for queer people of colour.

Given our inability to meet in person, the following interview is a compendium of various correspondences via email—before, during and after his residency as curator for Visual AIDS 2016.

Because I wished we were in Brixton, however, I began with the following question regarding his earlier work.

C.G. Smith: Was there a risk in making this intervention in the realm of representation, and if so, was it ever of concern to you?

AJAMU: To use an old rallying cry ‘the personal is political’ and self-representation is a form of empowerment. For too often the history, experience and achievements of Black British born queers do not appear in their rightful place, in records of our lives, history books, film, photography and I would argue that we are omitted from the social and cultural history of Black experiences and from within the wider LGBT community. Too often when a story is told, it is told by someone else. So for me as an artist, curator and activist it’s important that I tell my own stories through photography—to echo Gordon Parks, photography is my weapon of choice.

My images around SM, the politics of play, the rituals are in part exploring pleasures that are on the margins of Black and queer experiences. I feel while we are locked into the straightjacket of identity politics, most of our discussions around sexuality have forgotten to talk about sex, the dirt, the grit, the smells, and the sensual. And there appears to be little dialogue on other forms of sexual practices such as Brown (Scatology), Rainbow showers (Emetophillia), Handballing (Fisting).

I am interested in those people who, while maybe ‘out’ around their sexuality, are still isolated around their sexual practices. The images are not self-portrait in the sense that the images are not of me. The images do draw upon my own experiences in exploring Kink, SM as my alter ego Master Aaab.

AJAMU, Untitled #8, 1997, Silver gelatin print. Photo Essay.

All work includes an element of risk, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Risk for me can come in the form of working through ideas, including ones own identity, fantasies within public spaces. I am not necessarily interested in work that is trying to resolve anything but its how you play with and against binary thinking, holding apparent tensions or to put it another way, how do you articulate more nuanced experiences? I think there can be a danger of asking an artist what the work is about as images can not always capture some of the thinking—I see some of the images I created years ago as I do not think about the content but more about the feeling I was trying to convey, the technical aspects and the same image can evoke a whole range of emotions at different moments in time.

CGS: In one of your current projects, Fierce: Portraits of Young Black Queers, you continue this pursuit of representing Black queer lives, what made you decide to focus on Black queer youth?

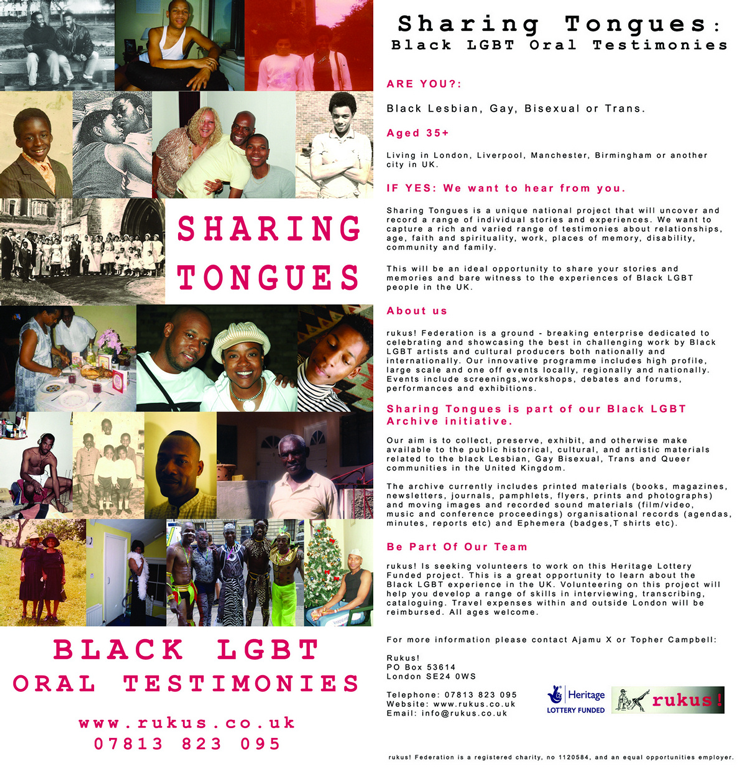

AJAMU: Fierce came on the back of another project called Sharing Tongues an oral history project which captured the testimonies of Black LGBT people over the age of 45, the eldest being 83 years old—the 50 + age group of those born in the early 1960’s in the UK would roughly be called a first generation of Black British born, and those of us who identify as LGBT would then be seen as a first Black British born ‘out’ generation. The sitters in Fierce are all roughly the same ages as my eldest nieces and nephews, so I wanted to create work around a cross-generational dialogue …the queer scene is bound up in ageism, so once you reach 45 + you’re seen as an elder (lol).

CGS: I’m getting to that age… (sshh) lol.

Sharing Tongues Flyer (front and back matter), 2008.

AJAMU: Fierce: Portraits of Young Black Queers was a continued development of my work in wanting to create a celebratory and aspirational lens in which to look at Black queer experiences outside the gaze of an oppression based narrative. There are very few spaces in which to have cross generational dialogues and I wanted to create a body of work on artists, activists, cultural producers who are to large extent a second generation of Black British born and also a second generation of ‘out’ Black British born. The last decade has seen major cultural shifts around social media and photography. We have seen many long-standing photographic companies shut down, many independent darkrooms have closed, so Fierce was also my return to nineteenth century traditional processes in particular platinum prints, and I wanted to insert Young Black queers into the tradition of the medium.

CGS: As the curator for Visual AIDS 2016, (in New York City) what initially intrigued you to take on this project?

AJAMU: Over the years I have worked with various archives, one of my favorites being The Ron G. Becker Collection, Syracuse University in which I explored Black and brown bodies in the context of side show performers and freak shows. In addition to this, I am the co-founder of the rukus! Black LGBT Archive, which collects and makes available materials relating to our lived experiences here in the UK.

The Visual AIDS archive is a unique archive that includes the work of artists who are HIV + and some are no longer with us. There is no such archive here in the UK as arts and HIV work are poles apart. So I wanted to engage with an archive that does not have a demarcation line between arts, HIV/ AIDS, and social activism. I also like coming across artists I have not heard of before as the archive provides that.

CGS: On the matter of Black queer image making and how it might serve as an intervention to current regimes of representation…

AJAMU: Too often we start a dialogue on our multiple and intersectional experiences from a position enacted in relation to an oppression based narrative, which by and large is circular. I don’t always find this helpful or always exciting, and this is not to dismiss peoples’ lived experiences. However, I am always interested in where the radical, independent, counter-cultural voices are.

AJAMU, Martez Smith: Community Organizer, HIV Advocate, 2016, Digital photograph.

CGS: Certainly. And what is to be done in our current moment? And I use the term ‘current’ loosely…

AJAMU: I don’t look towards the mainstream, including our own Black and LGBT mainstream for representation. I am far more interested in the work that is produced, and generated outside of formal structures and more likely to appear ‘below’ the mainstream radar within the arts and cultural sector.

I think there has to be a point of clarification on what is meant by our current moment, who is this ‘ours,’ what location are we talking from—does this moment coincide with other moments across time, space, Diaspora?

My focus for this residency did come out of my focus on young Black queers. However for this project I wanted to work with sitters who identify as QTIPOC. Some of the sitters were outside of my frame of reference, and I do not necessarily want to identity their ethnicity here. Yet, this is what such a residency brings. It’s an opportunity to meet more of the diverse, inspirational queers that cut across our community.

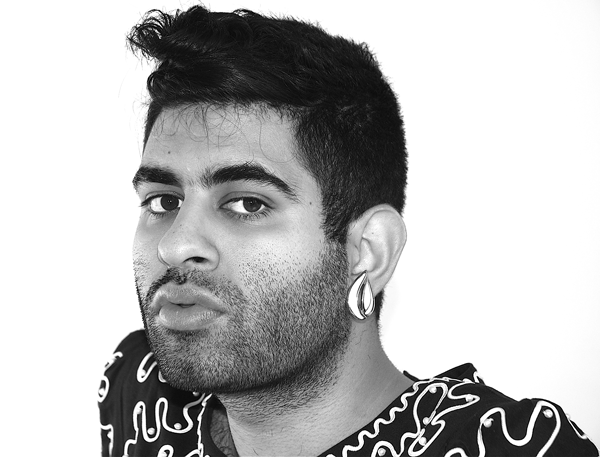

AJAMU, Alok Vaid-Menon: Performance Artist, Community Organizer, 2016, Digital photograph.

CGS: For the residency you articulated that the goal was ‘to develop an international Trans-Atlantic dialogue on archival activism, HIV and AIDS Activism and social justice within [your] arts based creative practice.’ How do you see this dialogue taking shape and subsequently continuing after the residency?

AJAMU: The residency was a starting point for a longer discussion. My first task was to photograph and film some of the current movers and shakers with the view of just listening to what their testimonies were. It is my intention to come back to develop a Fierce: NYC using the template from Fierce, which was created in London. It is my intention over the next few months to sit with all the filmed interviews and the footage that just documented everything and see where it leads me.

CGS: I’m wondering if you could elaborate on the ‘Suitcase under the bed’ workshop that was held during your residency.

AJAMU: ‘Suitcase under the bed’ was borne out of my own curiosity of what artists, activists, cultural producers and others keep in relation to their work and/or to any of their experiences. It was an opportunity for people just to share their personal narratives and hear each other’s testimonies. I am far more interested in offering the space to articulate the more nuanced experiences, the more tactile, the ephemera, the materiality, the sensual than these big clunky terms like ‘politics,’ ‘community,’ ‘identity,’ ‘representation’ allow us.

CGS: Unable to make it to NYC, I was inspired when AJAMU sent a link to the archive in the making, shortly after the end of his residency in early April. Understanding the role of representing and preserving Black queer oral histories, AJAMU’s residency marks a shift in the manner in which said lives are spoken about, and documented. It can be viewed here:

https://www.visualaids.org/blog/detail/video-interviews-from-ajamus-archiving-activists-project

Upon viewing the samples of interviews borne of the residency, a distinct and necessary counter-narrative appears. That is, the role of archival practices, and how we ensure that there is a more robust collection of material to provide a more nuanced history of HIV/AIDS. The history of Black women’s relationship to HIV, (either as impacted by, or living with) is often told in a protracted manner, or not at all. We need only recall the manner in which discourses of Black men on the ‘down low’ and how the experiences of Black women become framed and magnified as a consequence of non-disclosure either of sexual-orientation or HIV status (Thanks Oprah and J.L. King, smh). Such cultural moments result in a denial of the complicated manner in which Black lives are affected by HIV, and the necessary ability to narrativize and document perspectives about the matter that do not adhere to a discourse of containment often guised as ‘prevention.’ Art enables us to offer provocations regarding this matter. So I posited this question to AJAMU.

CGS: In our dialogues you mentioned that you were ‘inspired by meeting Kia Labeija in particular, and her work on being a woman, a Black woman, a visual artist and her work on HIV/AIDS—these are the narratives I want to hear and engage with.’ What struck you about her important interventions in relation to art and HIV?

AJAMU: I am inspired by Kia’s narrative for all the reasons stated: her being a woman, a Black woman, a visual artist whose work includes beautifully constructed self-portraits and her work on HIV/AIDS. Usually when we hear or see work on artistic practice in relation to HIV/AIDS it is by the usual white gay suspects (artists whose work I admire incidentally) so Black and brown narratives are always sidestepped. When I think about some of the sisters here in the UK who were involved in the late 80s with groups like BHAN (Black HIV/AIDS Network) and who were HIV+ and mothers. I do not recall seeing their children being present at the events, nor did I have a notion that their children were HIV positive or negative. What Kia’s narrative highlighted is my own blind spot and how we have to continue to drill down into many of our narratives we may take as a given.

Myself, understanding our engagement as an ongoing conversation, I inquired about the legacy of Black Feminism for many Black queer activists, artists and cultural producers. AJAMU offers the following inspiring frame to imagine a different future.

AJAMU: The sitters I have worked with articulate a whole range of positions and not just Black feminist ones. Since there are many Black feminisms operating simultaneously in regards to politics, geography, class, age, this makes it more challenging to give a clear answer. I am sure there are differences between first wave, second wave and maybe in the age of social media and new technologies a third wave of Black feminisms.

AJAMU, Seyi Adebanjo: Media Artist, Social Justice Activist, 2016, Digital photograph.

Each person I came into contact with was memorable in the sense of the range of conversations we had, connecting, sharing our testimonies laughing, playing. Including those people I met outside of the residency. If all those conversations were recorded it would have been awesome for the archive.

However, for me and one of my own personal missions around archival activism: how we think about archives is not what we go to but it’s what we bring with us. How do we bring ideas of pleasure, passions into archival work? How are we archiving always, placing archiving in the middle of all our social movement work?

CGS: In my engagements both as researcher of Black queer cultural production, and friend of AJAMU I am reminded of the ‘here and there’ of Black queer diasporic lives (to echo Jafari Sinclaire Allen).[2] I receive a note ‘Happy Queer Year’ on New Year’s Eve. Each year, I smile and I understand most importantly that the imagination is our best armor to thrive. It is for this reason that I close this interview with an inspirational provocation from AJAMU.

AJAMU: One of my favorite quotes that I try to inhabit around this work is by bell hooks:

‘surely our desire for radical social change is intimately linked with our desire to experience pleasure, erotic fulfilment, and a host of other passions.’[3]

[1] AJAMU. ‘Miss Tissue and the reinvention of the pussy-tongue (that’s cock for all you unenlightened children), in Golding, Sue (ed.). The Eight Technologies of Otherness (London: Routledge, 1997), 165-171.

[2] Allen, Jafari S. ‘Black/Queer/Diaspora at the Current Conjuncture’, GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, 18: 2-3, 2012, 211-248.

[3] hooks, bell. Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies (New York: Routledge, 1996), 29.

AJAMU is one of the leading historians concerning Black LGBT history in the UK. He has worked with a cross section of community organizations within the HIV/AIDS sector in the role of Black Gay Men’s Outreach worker, trainer and workshop designer for Gay Men Fighting AIDS (GMFA), as a freelance consultant, photographer and tutor, creating images for safer sex campaigns, as well as flyers and posters in relation to activism and social justice. As an independent archival curator, he is the co-founder of rukus! Federation. rukus! Federation is a non-profit organization known for its long-standing and successful program of community based work with Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans artists and cultural producers. The award winning rukus! Black LGBT Archive, launched in 2005, generates, collects, preserves and makes available to the public, historical, cultural and artistic materials relating to our lived experience in the UK.

Christopher Smith (aka C.G. Smith) is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Social Justice Education, OISE/ University of Toronto. His current project Apprehending Black Queer Diasporas: Transnational Circuits and Emplacements, examines circuits of political and cultural exchange that have shaped configurations of Black queer community formations in three global cities. By centering the phenomenon of Black Pride festivals as a counter narrative, this project highlights the complexity of LGBT equality and human rights pursuits in our current era through a queer diasporic lens.