Micah Malone

Since consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption…. The less toil there is, the more time and strength is left for artistic creativity. -E.F. Schumacher

The title of this essay comes from the great economist E.F.Schumacher’s book “Small is Beautiful.” A champion of appropriately sized operations and technologies, Schumacher wanted business and economies to be something more meaningful than a continual reach for “bigger and better.” Schumacher wrote eloquently about small, nimble, pragmatic and adaptive business models that could be the backbone of any healthy economy and reinforce a healthy and happy work force. This same logic might be applied to today’s contemporary artist, who at times seems to parallel that of the large-scale capitalist, perpetually scaling up in size, overhead and space, with the caveat that it is “more accessible” to mainstream citizens than other smaller, more austere projects.

It should not be surprising to say that when artists gain notoriety, access to more funding follows. This simple statement may at first seem like a banal reality, however, the transformation from unassuming beginnings that include low cost and innovative production methods, to artistic enterprises spending exorbitant amounts of money in development, production and maintenance is a story that should not be taken for granted. I do not trace this trajectory to evoke a cynical mistrust of expensively produced artwork, but question how much, if at all, more advanced production methods have complemented or expanded on earlier, more distinct efforts.

As funding for large scale projects begin to parallel the economies of Financial Investment groups, the autonomy of art and it distinction from other disciplines begins to blur. While “interdisciplinary” practice has become a hallmark of contemporary art, to retain a certain amount of autonomy remains the most productive way to allow for the most pressing questions about the nature of art.

My case studies involve established artists who occupy an unsuspecting relationship to the “market.” Which is to say, they are often left out of the conversation, as most critics and historians prefer more tangible examples – Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami and Damien Hirst – to speak about an artist’s relationship to economies. With so much attention paid to emulating mainstream industrial processes, other’s contributions are left out of the discussion simply because they do not represent a blatant link with consumer culture. If parodies (or realities) of factory operations dominate the dialog, then humble, skeptical and otherwise subversive practices get marginalized for their poetic and complicit desire to sell and show works of art in surprisingly new ways.

Chris Burden

As was widely reported, in March, 2009 Chris Burden’s Beverly Hills exhibition at Gagosian Gallery was cancelled due to an economic catastrophe involving high level financer Allen Stanford. The gallery reported that the SEC froze 100 kilos of gold bullions bought by the gallery for Burden’s exhibition while it investigated the improprieties of Stanford Financial Group, the parent company for Stanford Coins and Bullion who originally sold the bullion to Gagosian. Allen Stanford and his former top aides James Davis and Laura Pendergest-Holt are accused of selling fraudulent certificates of deposit issued by Stanford’s offshore bank and then of bribing regulators and accountants to ignore the allegations[1]. It should be noted that Gagosian is NOT complicit in any of Stanford’s illegal activities, they are simply experiencing the reverberations of his fall. Whether the bullion eventually gets delivered is beside the point, however, that Chris Burden and Gagosian Gallery are caught up in today’s toxic economic climate while producing a commercial art exhibition is noteworthy. Stanford’s arrest and the investigation of his assets have delayed one of art’s most notorious figures, but more interesting, it sheds light on the artist’s working process, one that has slowly inverted over the years.

This is not the first time Burden has incorporated gold bullion into his work. “Tower of Power” (1985) consists of 100 one-kilo pure gold bricks arranged in a pile on a marble base, with various matchstick men looking up at it. First shown in Hartford, CT at the Wadsworth Atheneum and later in Vienna, the gold was originally borrowed from a Rhode Island bank for the duration of the exhibition, at about 6% interest, according to the LA Times (who was quoting the Wall Street Journal)[2]. Worth about $1 million at the time, a Wadsworth curator told the Chicago Tribune: “We would hope the visitor to this exhibition can go beyond the thrill of the glitter, and what better way to illuminate the perception of art solely in terms of economic value than in a $1 million work in gold.”[3]

For the cancelled exhibition “One Ton, One Kilo”, Gagosian’s press release stated it would have paired a historical work with a new one. Safe to say that Burden’s plan was to include some permutation of “Tower of Power” with something that weighs “One Ton”, perhaps a wry juxtaposition between an abstraction of value found in gold and the weight of economic catastrophe America finds itself in.

In contrast to his work of the past decade, Burden’s early performances were surprisingly disciplined in their reductive qualities. Rarely did they require much material or produce any thereafter. Never were they documented or performed in obvious sensational ways, instead, the concept of the act itself carried the emotional and mythical weight. In “Shoot” (1971), perhaps Burden’s most infamous work, Burden was shot with a 22-caliber rifle from 5 yards away inside a Santa Ana Gallery. While Burden could have easily produced a spectacle for the event, the sole documentation is a grainy super 8 film lasting about 8 seconds. Those allowed to witness the event were the people making it happen: The artist, the shooter, the photographer and the gallery owner. In short, the theatricality involved in this piece does not spawn from Burden’s working methods, but in his conception of the work. The paring down of the elements that allow viewers access to his action feed directly into work’s ultimate strength: Burden successfully portrays what it feels like to be shot.

Burden’s overtly theatrical content (he was shot!) serves a perfect counterbalance to his modest, minimal and disciplined approach. “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb” (1979) is a masterpiece of economic logic and aesthetic restraint. In 1979, the Soviet Union had positioned 50,000 highly sophisticated tanks to stand guard along Western and Eastern Europe. The United States maintained only 10,000, thus, to account for and fully visualize this numerical imbalance Burden created “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb.” The installation of the work is simple enough: 50,000 nickels are arranged on the floor and 50,000 matches rest on top of these nickels and point West. Financially, the piece can be produced with just a few dollars for some wooden matches, as they are the only material costs to produce the work. Assuming someone is available to front the money for the nickels – a huge assumption – the nickels are borrowed from a bank and then liquidated upon the exhibition’s conclusion. This in itself can save hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of decades by avoiding storage costs (the piece is owned by MCA San Diego). Despite the almost unfathomable politically charged content, Burden’s approach is dry and calibrated, pragmatic in its ability to materialize and de-materialize the many elements.

Burden has not maintained this modest approach in years since, in fact, in might be argued that he has inverted his working process. For “The Flying Steamroller” (1996) a twelve-ton steamroller is attached to a pivoting arm with a counterbalance weight. The steamroller is driven around a circle with the pivoting arm at the same time a hydraulic piston is activated and pushes the beam from which the steamroller is suspended, causing the steamroller to lift off the ground and “fly.” An enormous amount of resources are expended for what is a very simple concept. The poetry of seeing a giant construction machine fly evokes the so-called dictum of “useless” art, by way of ironic juxtaposition. Instead of maximizing his limited resources for incomprehensible concepts, Burden has utilized vast resources (engineering and design teams, construction workers, grant writers, public funding, private donations, etc.) for more “whimsical” results.

The legal freeze on the bullion poses an interesting problem that poignantly addresses Burden’s graduation to larger, and more expensive projects. The acquisition of gold from a Rhode Island bank shares the same strategy of “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb,” in that both borrow currency for display. Someone to guarantee that currency is all that is needed. However, assuring 50,000 nickels and 3.3 million dollars in gold bullion require different scales of economies, and speak volumes about the growth and financial embrace of Burden’s practice. Gagosian Gallery (and presumably Burden) deciding to purchase the gold this time – or at least attempting to – erases the poetic and inventive borrowing that occurred between the bank and the institution in previous installments. It also put an onus on the gallery and/or collector to maintain the safekeeping of that gold, whereas before the bank took responsibility (it is what they do, afterall). Yet, even with all these resources the exhibition was canceled (or delayed) and millions of dollars frozen, and Beverly Hills Gagosian sat empty. It pays to be ephemeral.

Olafur Eliasson and Zumtobel Starbrick © Olafur Eliasson and Zumtobel, Photo: Jens Zieh

Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson certainly has experience with large-scale projects. His “Weather Project” (2003) in Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, along with his “New York City Waterfalls” (2008), are two of most discussed projects of the last decade, not to mention some of the most expensive[4]. Like most entrepreneurs, Eliasson has embraced diverse forms of output. In particular, his latest work packages his light and space experiments into a mass-produced modular component.

I first saw the ad for Eliasson’s “Starbrick” while leafing through Artforum’s December 2009 issue. The ad itself struck me as slightly out of place, as it wasn’t promoting an exhibition per se, only a mysterious star shaped light, seemingly sponsored by Zumtobel, who I later learned is an innovative LED manufacturer aiming to establish, “lighting standards into luminaire designs.” A visit to “Starbrick’s” website is something of a marvel in product promotion. The copy throughout the site is minimal, technical, yet focused and confident and made to appeal to both a contemporary art audience and a broader one. The photos effectively document and illustrate the many possible outcomes when assembled: “cloud-like structures as well as multiple basic architectural elements such as walls, whether freestanding or integrated into an overall structure, suspended ceilings, columns of all shapes, sizes and volumes.” As with all things modular, the installations are almost endless in their multiplicity and imply a myriad of options for purchasing. In fact, Eliasson says the stackable units are “generous” and, “makes it possible for people to buy a lamp system that can be related to its surroundings.” It is difficult to imagine a moment when high-end product development and conceptual art were more palpably linked.

Reservations for “Starbrick” are made starting January 2010 and shipping begins in February, presumably to anyone with 2,450.00 Euro (roughly $3,465 dollars). As with all forms of art that collaborate with outside industries (such as Murakami Prada bags), it isn’t clear how this gesture should be read. Does selling the work online and so non-exclusively effectively change its meaning? Domesticating the work certainly seems like the clear goal, however, a recent installation suggests “Starbrick” need not stay at home. For his solo exhibition “Your Chance Encounter” at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, Eliasson used hundreds of “Starbrick” units to “challenge the visitor’s sense of movement and orientation.”[5]

Eliasson’s desire to market “Starbrick” for homes as well as the museum implies the ultimate fate of “Starbrick,” (i.e. its future value as both commodity and fodder for academics) is determined by who ultimately uses the work. I applaud the idea that consumers and connoisseurs alike can determine the course of the work by way of how and who consumes it, in and out of the art world. Its fluid use-value may also be its most perverse feature, in that it is indiscriminate as art or design.

“Starbrick” is an object that is not only a lamp and a component used for larger, more substantial museum installations, but lives and circulates as an image, pictured in the promotional campaign online and in print. The strong arm of design hovers above this item, refereeing its slippery position in the world like a maneuverable datum. Mediation is so dominant that it can almost be thought of as the primary industry, reminding me of the polemic mantra by Bruce Mau in which he argues that in today’s environment, “the only way to build real equity is to add value: to wrap intelligence and culture around the product. The apparent product, the object attached to the transaction, is not the actual product at all. The real product has become culture and intelligence.”[6]

In many ways, Eliasson has entered into a Modernist argument about the role of art and design that has been waged since the later part of the 19th century. Whether it be Adolf Loos’ insistence on sleek “natural” forms (while simultaneously denigrating ornament), the elevation of the utilitarian stemming from the Bauhaus, or Donald Judd’s awkward “visible reasonableness”, more often than all of these paradigms insist on outlining objective limits and distinctions between “use-value” and “art-value.” The value of finding these limits, to paraphrase Hal Foster, is to give the “designed subject” some “running room” that allows, “for the making of a liberal kind of subjectivity and culture.[7]” What is missing in Eliasson’s project is the conceptual space for a subject to construct their own experience, to craft and imagine their own position within an overly designed environment, something Eliasson accomplished in earlier works.

In his first solo museum exhibition at the ICA Boston (while it was still in the old firehouse) in 2000, Eliasson presented an installation in which a pool of water was built with 2 x 4s, plywood, plastic and other common building materials. Seeing the underside of this humble ramshackle structure as you climbed the stairs was an integral part in experiencing the work. The temporal quality of the structure made one approach the viewpoint at the top of the stairs with some trepidation and excitement. Reaching the top of the stairs enabled viewers to gaze upon a darkened room-sized pool that reflected a hanging swirl of neon that hung above the water. The calming beauty of the artificial reflection was only intensified by the temporal, unfinished quality of its fabrication. One could easily visualize the work’s dismantling upon the exhibition’s closing, only to concentrate again on the calming neon and water and forget one is inside a gallery, which is itself inside of a museum. To imagine both the work’s construction and completion through their time spent was an integral idea that gave the exhibition’s title: “Your Only Real Thing is Time.”

To imagine a dismantling of a “Starbrick” installation, one dismantles a finished complete component, a unit, all the while masking the work and labor that created it: A draftsman, a host of engineers, a graphic designer, a copywriter, a technical writer to draft the instructions, not to mention the tooling and shipping teams to manage the fabrication and subsequent distribution. Contrary to this expansive team, the works at “Your Only Real Thing is Time” were likely executed with a few drawings and a host of arthandlers to execute them. It is tempting to see the transformation of modest, yet ambitious carpentry, to industrial production as one of advancement. After all, the complicated injection-molded polycarbonate components and LED lighting that control the majority of Eliasson’s work now is certainly something to marvel at. However, to say it advances his ideas in more meaningful ways is questionable.

What this project attests to is the desire for a seamless convergence of industrial design, product promotion and art discourse. This is not advancement so much as art becoming regressively indistinct. There is a value at which a functional object can get flattened into the world of signs, becoming too valuable too carry on its function (Original Bauhaus furniture comes to mind), a space where social value ultimately replaces use value. With “Starbrick,” Eliasson wants all these values at once: The social value of art along with the use-value of good design represented in a pictorial sign that can navigate through all realms of culture. He attempts to circumvent what gives each of those disciplines real value: the running room and scope for debate for others to ultimately decide what it means.

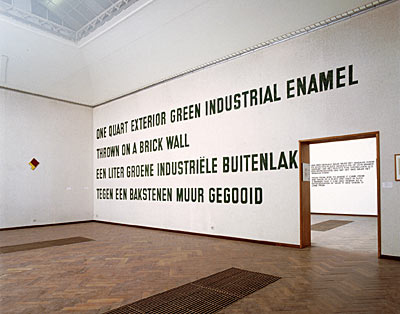

Lawrence Weiner, One Quart Exterior Green Enamel Thrown on a Brick Wall, 1968, dimensions variable, private collection, installation in Lawrence Weiner: Works From the Beginning of the Sixties Toward the End of the Eighties at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1988–89, Image courtesy of MoCA, Los Angeles

Lawrence Weiner

It is tempting to liken Eliasson’s desire for multiple contexts akin to the work of Lawrence Weiner. Both enjoy the proliferation of “venues” in which the work might be viewed. Indeed, spanning a 50 year career Weiner has produced work in sites as varied as museum walls, billboards, matchbook covers, coins, sewer covers, building façades, to name only a few. However the plethora of contexts available for Weiner differ greatly from Eliasson and point to a very different type of practice, one that is decidedly democratic.

Weiner’s art succeeds, in part, from his insistence on support from a market that is ultimately divorced from other, more mainstream economies, a continually evolving and changing market that ebbs and flows by the whim of his consumers. From his start as a painter in the early 1960s, his route involves starting with little and graduating to virtually nothing, all the while disseminating it just about everywhere.

The works that Weiner began during the early 1960s called the Propeller paintings appropriated the motif of the TV test pattern. At the time compared to Jasper John’s “Flag” paintings as well as Lichtenstein’s cartoons, reviews commonly asserted Weiner was more interested in the “idea” of a painting than an actual painting. However, viewing some of Weiner’s installation shots from his 1964 exhibition at Seth Siegelaub Fine Arts Gallery, composition, color and design were prominent. There were decisions made about the size of canvas, the scale of the propeller in relation to the canvas and how large the outlines around the propeller in each work related to the frame, not to mention his distinct color palette. These works show Weiner’s early interest in formal nuance, and show a precedent in his subsequent use of bold and decorative typefaces.

A body of work followed in which formal decisions were further limited. In each “Removal” painting, a small rectangular notch was removed from the bottom frame of the canvas. These, unlike the “Propeller” paintings, were not hand painted, but made with a spray gun and compressor, further removing any “touch” the artist might have had. In addition, Weiner gave instruction to anyone receiving the work: “The person who is receiving the painting would say what size they wanted, what color they wanted, how big a removal they wanted.”[8] This resulted in deadpan titles such as “A Painting with a Piece Removed, etc., for So-and-so” or “A Painting Done in California for So-and-so.” Donna De Salvo emphasizes this was “another means of bringing the viewer into active participation.”[9] However, it was also a way to bring the collector into active participation, a collaboration in which artist and patron could take risks together. A running dialog with his collectors must have given him confidence to take the greater risk of making an object or gesture equal to the language describing it.

“A Square Removal from a Rug in Use” (1969) is at once a sculpture but also a vehicle for information. Originally, a collector asked Weiner to realize the piece, in which he responded by literally removing a square from a rug inside the collector’s home. That particular rug was only a version of the concept and had no value in and of itself. If the collector moved, a different rug that was in use would then have a square removed. The linguistic utterance becomes as important as the act itself, and in time, Weiner found a way to sell these language-based works that may or may not be realized – or realized and then destroyed and made again later in different ways. Weiner’s infamous “Statement of Intent” guided the structure of his ensuing work:

1. The artists may construct the piece

2. The piece may be fabricated

3. The piece need not be built

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the condition of receivership.[10]

Weiner’s “Statement of Intent” carves out a particular type of market he aimed to occupy. Over the course of almost a decade – the early 60s to his statement of intent of 1968 – Weiner managed to lead a handful of collectors and patrons from propellers and collaborative removals to poignant gestures that could be materialized (or not) depending on their own whims. In Alexander Alberro’s excellent book “Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity” he refutes standard accounts of conceptual art’s desire to negate the commodity status of art. Generally speaking, none of the conceptual artists wished, or even thought possible to abolish art’s commodity status. Collector’s and dealers had to grapple with how to own these works, but Alberro states, “there was never a moment when they did not seek to market the art.”[11]Weiner’s increasingly spare and temporal works, or “art as idea,” were not exactly indictments on the art object, but an expansion of what could be bought and sold. Joe Scanlon wrote that he “critiqued the market by making commodities in forms that it did not yet know how to evaluate.”[12]

Weiner once said that his “Statement of Intent”, “presents a sculpture, but it doesn’t tell you how it should look.”[13] The fluid nature of the work never forces a subject to realize an exact image. Rather their own subjective experience, or “running room” allows them to bring alive the work in a way they see fit, including only imagining the statement. One mode of presentation first developed when the prominent collector Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo elected to have Weiner’s work installed directly on the walls of his residence. The bright typefaces and colors applied directly on walls with paint or vinyl letters have become synonymous with the artist since that time.

Flipping through the catalog of Weiner’s recent retrospect “As Far as the Eye Can See,” it was astounding to see the many ways his work has been utilized. I paused on a picture of a large private swimming pool with some pool side chairs and a table near the edge of the picture frame. The water is a beautiful pale blue and adhered to the bottom of the pool is one of Weiner’s familiar bold font types in black against a bright red background: STRETCHED AS TIGHTLY AS POSSIBLE/ (SATIN) & (PETROLEUM JELLY). Perhaps the phrase itself has been stretched as tightly as possible across the pool’s bottom, or maybe the collector simply liked the phrase and wanted a bold and theatrical presentation of it. I like to imagine all sorts of other artworks inside this unattributed residence: Large Jeff Koons sculptures, big paintings by Takashi Murakami, perhaps a Dana Schutz behind a monumental Urs Fischer. Any of the usual suspects in the contemporary art world suffice my daydream. This particular iteration of Weiner could be perfectly complementary to these works. Its large scale and dominant, yet welcoming presence makes it seem like the pool was built for it. As artists lose or gain favor over time, decisions about what to do with their giant, cumbersome works will have to be made. The same goes for Weiner, however, decisions about Weiner are never final and can be endlessly changed and re-thought. It is unclear what his work will look like in 20, 30 or 100 years, in part, because people may or may not be electing to manifest it at that point in time. However, if they elect to, they will imagine an appropriate way to materialize it, one that fits with their current tastes. Weiner’s allowance for others subjectivity permits this pleasure.

[1] The Washing Post reported on June 20th, 2009 that the Securities and Exchange Commission charged that Stanford’s operation was a Ponzi scheme — second in size only to the Bernard Madoff fraud that broke in December, 2008. The SEC alleges that up to 30,000 investors — including elderly people living off investment returns — were defrauded.

[2] Mike Boehm. “Gagosian Gallery and Chris Burden hit legal obstacle in launch of glittery show.” Los Angeles Times,March 2, 2009. “Culture Monster” online.

[3] As reported by Boehm.

[4] Carol Vogel reported for the New York Times that the initiative for the waterfalls cost $15 million. See “From a Master of Weather, 4 Waterfalls for New York”, New York Times, June, 2 2008.

[5] Starbrick/Zumtobel. http://www.starbrick.info/en/press.html. Accessed February 2010.

[6] Bruce Mau. Life Style (London: Phaidon Press, 2000).

[7] Hal Foster, Design and Crime (and other Diatribes) (London: Verso Press, 2002)

[8] Alexander Alberro, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2003), pg. 89 The quote can also be found in Lawrence Weiner, interview with Patricia Norvel, 3 June 1969, in Alexander Alberro and Patricia Norvel, eds., Recording Conceptual Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 136

[9] Donna De Salvo, “As Far as the Eye Can See,” ed. Donna De Salvo & Ann Goldstein, Lawrence Weiner: AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), pg. 65

[10] This statement is reprinted is virtually every essay on Weiner. It was first published in 1968 as part of a catalog published by Seth Sieglaub. See Barry, Huebler, Kosuth, Weiner, exh. Cat. (New York: Seth Sieglaub, 1969), n.p. It can also be found in (De Salvo, pg. 65)

[11] Alberro, pg. 4

[12] Joe Scanlon, “Modest Proposals,” Artforum (April 2008), pg. 317

[13] De Salvo, pg. 70

Micah Malone is an artist and critic based in Portland, Oregon. He graduated with his M.F.A. from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where he also helped launch the arts journal Big RED & Shiny. Currently, he serves as an Executive Editor and is on the Board of Directors in addition to writing reviews for Artforum.com. His work has been exhibited nationally at venues such as the Autzen Gallery at Portland State University, Worksound Gallery, in Portland OR, the Mills Gallery, GASP Gallery in Boston MA and the Contemporary Arts Collective in Las Vegas NV.