Lena Pozdnyakova

Western art actually has two avant-garde histories: one of artlike art and the other of lifelike art. They’ve been lumped together as parts of a succession of movements fervently committed to innovation, but they represent fundamentally contrasting philosophies of reality […]. Simplistically put, artlike art holds that art is separate from life and everything else, whereas lifelike art holds that art is connected to life and everything else. In other words, there is art at the service of art and art as the service of life.[1]

–Allan Kaprow

Thought Bubble#1:

DUAL NATURE

In the 21st-century art world, manifestations of socially-engaged art are hardly a surprising event. With the form gaining prominence in the late 20th century, socially-oriented works have now received wide public acceptance and have grown into diverse collaborative practices that involve artists, various institutions, and the public.

Contemporary expressions of socially-engaged practice often involve a large pool of participants and take a broad range of forms: conceptual works that imply social commentary, activist enactments, humanitarian projects, pedagogical and cross-disciplinary social practices. Timeframes for these experiences vary drastically. Some of the works include long-term scripted scenarios and incorporate complex production schemes involving large institutions and diverse participant groups. Other pieces are short-term events and exist in real-time and are independent from institutional support. A distinct feature that unites many of these works is the intention to raise awareness and promote inclusion and equity by politically and socially engaged artistic acts.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Allan Kaprow envisioned the transition towards art at life’s service with the emergence of lifelike art, a term coined by the artist. For Allan Kaprow, the expansion of the art practice meant the inclusion of non-art environments and activities.

Despite Kaprow’s hopeful ideas, the lifelike feature of socially-engaged practices has revealed several controversial issues embedded in the idea—specifically, its relationship with institutions, its public, and the art market. Among the problematic issues embedded in expanded socially-engaged art, we can list the institutionalization of emancipatory experiences, commodification of democratic and free-speech expressions, objectification of the artist’s and participant’s body. It is hard to argue that, despite the popularization of socially-engaged practices and artists’ intentions to bring good to many in real-time interaction, many of the socially-engaged projects showcased in cultural institutions feel like coordinated, set-up, short-term performances and, frankly, are far from providing the authentic and lasting experience of events outside the museum.

We might ask why it feels this way.

Thought Bubble#2:

BLURRED LINE

In Artificial Hells, Claire Bishop provides us with a broad survey of participatory works from modernism onwards, pointing to the gradual expansion of art towards a more inclusive form of engagement. According to Shannon Jackson’s account, the definitive “social turn” in participatory art gained its strength only towards the end of the 20th century[2], when, due to the growing interest in socially-engaged artistic practice and its effects, the art world opened up to include humanitarian and community-driven activities. With this expansion, critical polemics in the field surrounding these expanded engagements addressed one particular issue embedded in socially-engaged art practice—its intention to blur the line between art and life in involving stakeholders outside of the art world.

To address the difficulty in defining the boundary between life and art, since the 1990s, art historians and critics have offered a new vocabulary of terms. These terms included Nicolas Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics,”[3] Nina Felshin’s “activist art”[4], Suzanne Lacy’s “new genre public art” 11, Tom Finkelpearl’s “dialogue-based public art”[5] projects, Grant Kester’s “dialogical art”[6] and Miwon Kwon “site-specific” art[7]. Notably, these terms emphasize the relational aspect of the work and point us to the importance of public domain and shared environment.

In her book “One Place After The Other,” Miwon Kwon specifies the role of the site and offers a genealogy of socially-engaged art, where the transition that expands the field to include non-art environments and stakeholders is set precisely in artists’ critical approach to site as a component of the artwork.[8]

She suggests that socially engaged practices have gradually developed from the institutional critique works that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s.

An illustrative example that shows this transition is a series of works by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who, since the late 1960s, is approaching art as a form of maintenance, with early works manifested as institutional critique. As part of her piece “Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside” (1973), Ukeles has scrubbed the museum’s outdoor staircase, raising gendered issues and redefining the artist’s role with its relation to the art world’s protocols and settings.

Employing maintenance work as a form of performance during the 1970s, she explored the notion of the body, collective culture, and service. With her durational approach to the production of works, she soon became involved in the New York Department of Sanitation’s public service, where she worked for more than 30 years as an artist-in-residence.

Without ascribing to the concept of lifelike art, or The Happening, Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s work emphasized a similar concept—an expression that connects life activities and art, which she called “Life Instinct.”[9] In her 1969 “Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Proposal for an Exhibition “CARE,” she positions the act of service to the foreground and defines her maintenance work outside of the art world to be the expression of art. By doing this, she opened up new environments and roles for artistic practice. In her later works, she merges life with art practice by serving on the sanitation service’s daily routes as part of her art practice.

Socially-engaged works in the late 20th century, according to Kwon, engaged with larger institutions and diverse stakeholders. This shift further blended the boundary between the non-art activities and art practices. An example that demonstrates this change is the “Culture in Action” program, organized by the Sculpture Chicago Organization. The program rejected conventional art formats and instead commissioned artists to work with communities through political marches and workshops.

Kwon’s narrative on the development of the form emphasizes the site’s critical role. Within the artwork, the project’s environment becomes an inherent part of the piece and often frames all the other elements, including settings, artists role, and the audience’s experience.

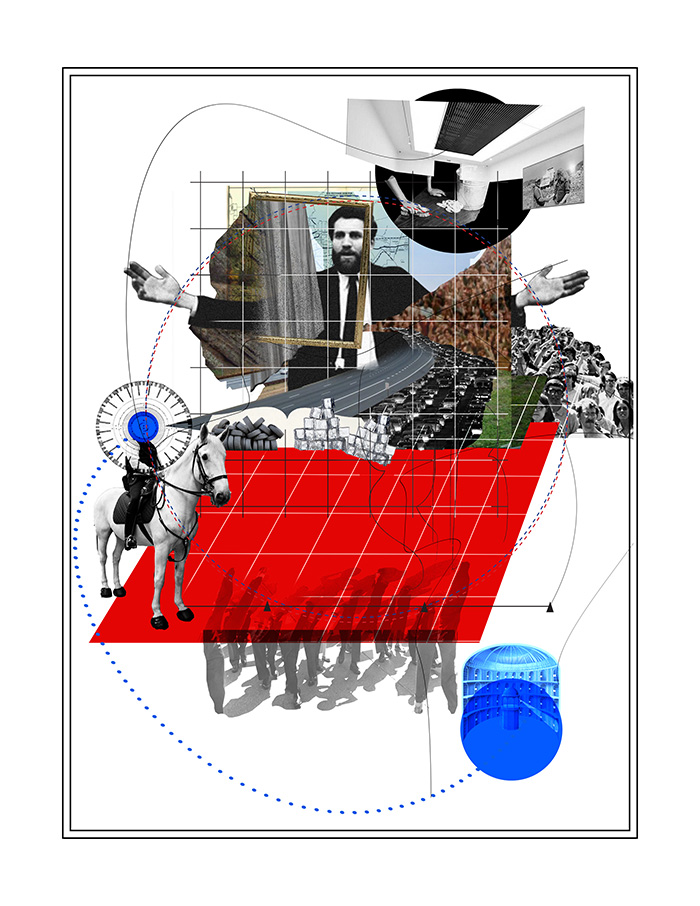

To further illustrate the site’s critical role in lifelike art within a more contemporary context, we can review two contrasting works from Tania Bruguera—Tatlin’s Whisper #5 at Tate Modern Turbine Hall and her residency project in New York with Immigration Movement International.

The first piece incorporates elements of impromptu lifelike performance with surveillance of the public as the core element in work. During the event, the audience was surveilled by two mounted policemen patrolling the Turbine Hall. The confrontation of the mounted police and the public signified the conflicts from past years. For the artist, this referred to the larger collective memory of traumatic historical events that involve police enforcement and power manifestation. The work’s essential element was that the audience was unaware of the performance taking place, believing that the surveillance was a real-time event.

In contrast to Tatlin’s Whisper, Bruguera’s earlier work that addressed the immigration issues incorporated her moving in with a group of illegal immigrants in a small apartment in Queens. Her residency with five people and six of their children part of a year-long lifelike art piece as part of Immigration Movement International.

While examined pieces differ in their execution, one can sense that the closer the work comes to the renowned cultural institution in its performance and execution—the more evident its connection to the art world and the less authentic it is as a life event.

With the key overlapping features presented in mentioned above works, the critical trait—participatory component set in real-time and real-life environments conveying the authenticity of lived experience—tracks its origins back to Kaprow’s idea of lifelike art as an extension of art as a service of life.

Thought Bubble#3:

ORIGINAL IDEA

Inspired by the political, social, and cultural activism in the 1950s and 1960s in the US, Allan Kaprow theorized on the importance of non-conventional and open-ended artistic engagements, interactive and durational in execution.

Kaprow summarized these ideas in by the term The Happening. He defined it as it follows:

…an assemblage of events performed or perceived in more than one time and place. Its material environments may be constructed, taken over directly from what is available, or altered slightly, just as its activities may be invented or commonplace. A Happening, unlike a stage play, may occur at a supermarket, driving along a highway, under a pile of rags, and in a friend’s kitchen, either at once or sequentially. If sequentially, time may extend to more than a year. The Happening is performed according to plan but without rehearsal, audience, or repetition. It is art but seems closer to life.[10]

Therefore, in Kaprow’s work, we can see two things: the first is that the intention has to be a departure from institutions such as museums and galleries, and second, it was to be as real as possible, aka “lifelike art.” For Kaprow, Happenings were a form that creates spontaneous action with aleatory outcomes. Kaprow’s Happenings were usually performed by amateurs and friends, with common materials used in uncommon ways and sites.

Fluids and Eat are good examples of these ideas put in place.

In Fluids, Kaprow brings in ‘sub-contractors,’ people not directly related to the art world, to participate in an event. With the collective action of building from ‘ice’ that was literally about to melt, Kaprow expressed the critique of both the art market and urban development taking place in Los Angeles at the time.

Another famous example of direct commentary about the art world is Kaprow’s Eat. The happening took place in dimly lit caves, equipped with food and drinks for the audience. The atmosphere was the critical element– the darkness of the cave, sounds of ticking metronomes set to the rhythm of the human heart created the distance between the gallery’s traditional settings or the museum and the viewer. In Kaprow’s view, this distance was that gap between the art and life that he aspired to allow for the audience’s experience.

Often, the performances were not closely directed by Kaprow, and instead, they were acted out by way of a simple script and documented mostly in still black and white photos; not many videos or film depictions can be found even though it would have been available at the time. Kaprow often expressed his views against lifelike art commodification and proposed it to be an emancipatory project that will change an artist’s role in society.

In sharp contrast to minimalist sculpture and abstract painting of his contemporaries, his works’ intentional lack of control brought Kaprow a renowned reputation and broadened Happening’s exposure within the art world. Working from the acclaimed artist and pedagogue position, Kaprow himself had naturally set a path for institutionalization of The Happening as an expression of his idea for the lifelike art.

Thought Bubble#4:

POINTS OF FRICTION

While in Kaprow’s terms, lifelike art incorporates contents of everyday life, with its events and participants, shifting the performative interaction towards places and occasions of everyday life, art historians and critics have defined a set of controversial issues embedded in the idea.

In her essay, “Happenings: an art of radical juxtaposition,” Susan Sontag points us to the role of participants and audiences in Kaprow’s works and reads it as “material objects.”[11] Bodies, situations, and lifelike moments during the reenacted lifelike practices or emancipatory practices shown within art institutions’ walls become components of abstraction or conception in itself. By reading the event as “assemblage,” we get the sense that Kaprow exerted a certain form of bodily discipline despite his efforts to obscure his authorship.

In this sense, treated as anonymous and collective forms, bodies of participants resemble the notion of Foucauldian “docile bodies.”

“A Spring Happening” (1964) is one example of the extreme forms of interaction in Kaprow’s Happenings. During this happening, the participants were standing in narrow tunnels and were exposed to quickly flashing lights and unpleasant to ear sounds. During these performances, people would often leave the room triggered by the sound and overwhelmed with the unpleasant experience.

In her critique of relational aesthetics, Claire Bishop outlines the importance of attention to the roles inhabited by participants in art events.[12] She states that while sharing the experience, the audience’s ideals may differ from that of an artist, therefore setting an uneven assemblage of intentions within the socially-oriented event.

A further problem, or perhaps an obstacle to this notion of free and open-ended experience, appears when we turn to the present day, where Happening-like performances have become a norm. Rather than an everyday life filled with unexpected aesthetic experiences, artists such as Tino Sehgal, Tania Bruguera, Ai Wei Wei do works specifically for institutional settings, often in the same institutions that produce reenactments of famous performances from the 1960s. Hal Foster calls this phenomena “zombie time.”[13] In the chapter “In Praise of Actuality,” published in Bad New Days, he raises the problem of displaced time represented in reenacted performances from the 1960s and 1970s. “Not quite alive, not quite dead, these reenactments have introduced a zombie time into these institutions.”[14]

Thought Bubble#5:

ART EXPANDED TO EMBRACE LIFE

As we have seen, Kaprow’s works have unraveled a particular entanglement of two opposite notions embedded in the attempt of merging life and art—an emancipatory side (critical and liberating) and a biopolitical aspect as the subjection of the public to power (functioning as a mode of bodily control by an institution, author, or the market).

It is clear that pitfalls within the participatory aspect in socially-engaged art practices, arguably, underline the dichotomy embedded in what Kaprow’s lifelike art concept attempted to put in a system: an openness and aspiration to expand beyond the art world to rethink strategies for redefining and reentering public space through collective action, while also ascribe the engagement to the distinct field of art.

Kaprow’s works and ideas, as a departing point for this discussion, have been firmly set in the politically and socially charged 1960s, when the artist’s emancipatory role in society and culture was central to his ideology and writings. The participants for him “were not professionals or performers, but “disseminators of ideas.”[15] Therefore, despite the various ways that Kaprow’s work is recuperated into the art world’s material and institutional power, at the time of Happenings’ emergence, his work effectively pushed back against these structures, widening our consideration of artistic experience and inspiring other artists for free and open-ended practices that paved the way for socially-engaged projects as we know them today.

Once one understands the ambitions of Kaprow’s ideas and the social and political upheavals through which the idea of Kaprow’s lifelike art is understood [counterculture, the sexual revolution, anti-war, etc.], it becomes impossible to experience socially-engaged art of the current age in the museum and not feel a sense of loss or retreat from the real-time and real-life experience of the world outside the museum.

Unlike those revolutionary ideas of the 1960s, participatory works that are choreographed within the museums today are probably better understood as reenactments of life rather than authentic experiences happening in real-life situations.

With this in mind, I am prompted to view the current shift and departure of contemporary socially-engaged artworks further from museum sites and into real-life situations as a tremendously promising opportunity for the expansion of the field to the extent that even Kaprow hadn’t fully envisioned. And despite the set of critical problems concerning the embedded difficulties on ontological, disciplinary, and ethical levels that continue to emerge as a result of participatory art’s expansion, it seems that this departure from the confines of institution opens up room for discussion on the expansion of discursive fields that surround art production.

In this regard, Grant Kester advocates for a “cross-disciplinary art criticism”[16] for reviewing the relationship between performative practices and the social sphere. He proposes to approach participatory works that interfere with the social sphere with an expanded understanding that allows for the merging of art criticism with sociology, anthropology, and ethnography. This method may be a challenging one, but it certainly seems to be the one that can push the territory of artistic production and knowledge towards what Kaprow had identified as art “at the service of life.”[17]

In her article on reenactments of Kaprow’s works for New York Times, Jori Finkel noted “that it was no wonder that while Kaprow taught at CalArts alongside Baldessari, many of Baldessari’s students became famous artists, and many of Kaprow’s students “went on to become social workers, zen Buddhists or chiropractors.”[18] With reference to Kaprow’s lifelike art ideas and current discussion on the extension of context for socially-engaged art in the expanded field of production, Kaprow’s students, social workers, zen Buddhists, and chiropractors, may have gone further than producing art for the sake of art and perhaps have, on some fundamental level, fulfilled Kaprow’s intention of serving life as an expression of art.

[1] Allan Kaprow, “The Real Experiment,” in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley: University of California 1Press, 1993), p. 201.

[2] Shannon Jackson, What is the “social” in social practice?: comparing experiments in performance”, ed. Tracy C. Davis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p.139

[3] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasauce and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les Presses du Reel, 2002), 112-113.

[4] Suzanne Lacy, ed. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (Seattle: Bay Press, 1994), 19.

[5] Tom Finkelpearl, Dialogues in Public Art (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), x.

[6] Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 19.

[7] Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site‐Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002), 4.

[9] Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “Manifesto For Maintenace Art 1969! Proposal for an exhibition ‘Care’.”; Originally published in Jack Burnham. “Problems of Criticism.” Artforum (January 1971) 41; reprinted in Lucy Lippard. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object. New York: New York University Press, 1979: 220-221.

[10] Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 201.

[11] Susan Sontag, “Happenings: an art of radical juxtaposition”, in Against Interpretation: And Other Essays (New York: Picador, 2001), 265.

[12] Claire Bishop, Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics, in October 110 (Fall 2004), 70.

[13] Hal Foster, “In Praise of Actuality”, in Bad New Days: Art, Criticism and Emergency (London: Verso, 2015), 127.

[15] Richard Schechner and Allan Kaprow, “Extensions in Time and Space. An Interview with Allan Kaprow”, The Drama Review 12, 27 No. 3 (Spring, 1968),167.

[16] Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “A Note on Socially Engaged Art Criticism,” Field 6, Winter 2017.http://field-journal.com/issue-6/a-note-on-socially-engaged-art-criticism

[17] Allan Kaprow, “The Real Experiment,” in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley: University of California 1Press, 1993), p. 201.

[18] Jori Finkel, “Happenings Are Happening Again,” The New York Times, April 13, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/arts/design/13fink.html

Lena Pozdnyakova is an alumna of the Design Theory and Pedagogy program at the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles. She has earned a Bachelor in Architecture Degree from Sheffield University and a Masters in Architecture from DIA University of Applied Sciences. All the programs were funded with Scholarships. Currently she holds a position of Project Coordinator and Researcher at xLAB think tank in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA. Lena has previously worked in UrbanDATA Bureau (Shanghai) and in 3Gatti (Shanghai). Deciding to go further into multimedia installations, she became part of the2vvo practice, a project for interdisciplinary research. Since 2014, she has exhibited works at Bauhausfest, Unsound, CTM and Soundpedro Festivals. In 2014, she received Robert Oxman Prize, and in 2016 as part of the2vvo, Independent Projects Award by CEC Artslink. Upcoming exhibition ARCHIVE MACHINES showcases the2vvo’s “Attention Environments #1”piece at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and runs from July 30 to November 1.