Zoe Beloff

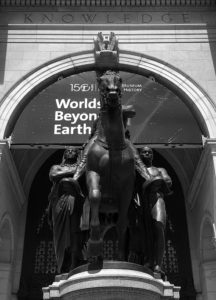

Zoe Beloff, The Theodore Roosevelt Statue, 2020, iphone photographs. Images courtesy of the artist.

Setting the Stage

Arriving at the main entrance of the American Museum of Natural History one is confronted by a great bronze statue. On a pedestal mounted on a monumental staircase stands Teddy Roosevelt on horseback, armed with pistols and flanked by two figures, a Native American and a Black man, allegorical representations of America and Africa. It was constructed in nineteen forty. Roosevelt’s father was a founder of the Museum. Below, a group of white men wearing MAGA hats are unfurling American flags. The statue, long seen as controversial is now officially to be removed. Its fate remains uncertain. These men are here to stage a protest, advocating for the statue and for themselves. They speak of white genocide. I arrived to document the statue for my own purposes and am completely unprepared when they welcome me to their cause. Instinctively, without thinking, I start screaming, “You make me ashamed! Bigots!”. I am hysterical, trembling with rage, beside myself. They call me a Communist. One young man yells back, “You think all lives matter but mine!”. And I, confronted by men, who in my eyes might have been Brown Shirts in another era, had no reply. Later I think back, if only he could have heard himself. I sensed fear masquerading as anger, that of a scared child, terrified of being abandoned. It is no wonder that he sought to take shelter under a great white man. More than ever this exchange brings home to me the power of the statue as wish image.

Reading the Statue

The statue is a scene staged at a specific place that tells a story, that is also an allegory. The place is the entrance to the Museum above which the word, knowledge is carved in stone. Thus, what we see before us takes on the aura of truth as immutable as the stone itself. Behind the statue is a banner proclaiming Worlds Beyond Earth, the last exhibition before the pandemic shut the museum down. This is a museum that above all traffics in time, in all its multiple registers, from cosmological time, to geological time to evolutionary time on our planet. And it is in this register that the statue invites us to read it as an evolutionary pyramid. The great white man at its apex supported by indigenous men flanking his horse. Teddy takes on the trappings of all white men, marching into the future, an allegorical figure of imperial power, call it, mastery over nature, represented here as figures, that once would have been labelled ‘savages’, marching into the future, complicit in his enterprise.

Only today, the Museum must confront a new kind of time, the revolutionary time that demands social change now. Today, all over the country, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, people are calling for statues to be torn down. I agree with the calls for confederate generals to be ground into gravel. Yet, here at the Museum, beyond the twin poles of domination and demolition, elevation and erasure, I propose transformation, out of the ruins of the Theodore Roosevelt monument, the creation of something new, a dialectical image, history reimagined. Let us not erase the past but make visible the struggle towards equality.

The Gaze

Well, why shouldn’t this monument be melted down in the scrap of history? What could possibly be redeemed? My first clue is in their gaze. The gaze of America and Africa is introspective, brooding. These figures are presented as thinking beings. It is at this moment that I glimpse something that one might call a potential that transcends the clichéd representation of the ‘noble savage’ that surely weighs heavily on them. But how can we create the conditions for this potential to come into its own?

The philosopher Walter Benjamin, wrote that the task of materialist historian is to bring to light history that has been suppressed.

In blasting an object out of the past… he recognizes a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past… The only historian capable of fanning the spark of hope in the past is the one who is firmly convinced that even the dead with not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious. And this enemy has never ceased to be victorious.[1]

The enemy, he writes, is the one who sides with the victors of history, that is the dominant culture. As he puts it, all documents of culture are at the same time documents of barbarism. The materialist historian must “brush history against the grain”. That is, I believe they must make this barbarism visible. We do not know their names of the dead, but it is to them that our new constellation of figures must be dedicated. As Benjamin puts it, “It is more difficult to honor the memory of the anonymous than that of famous people. The historical construction must be dedicated to the anonymous.”

For a split second two gazes meet, that of the materialist historian and the statues Africa and America. Benjamin puts it poetically, “Articulating the past historically means recognizing those elements of the past which come together in a constellation of a single moment…. In drawing itself together in the moment – in the dialectical image – the past becomes part of humanity’s involuntary memory.”[2] But how can we even begin to articulate this?

No Pedestals!

For two gazes to meet, each person must confront the other from a position of equality, both able to look each other in the eye. Therefore, I believe that all statues must be removed from their pedestals. The expression, to put someone or something on a pedestal explains why. No one should be in a position to look down on someone else. Not only must the pedestal be dismantled but Teddy must be unseated from his horse, which is of course simply animal as pedestal, so that he too is brought down to earth to level with his companions.

It will not be easy to sever Teddy from his steed, and from the allegorical figures that prop him up. Most likely a blow torch will have to be used. All will bear deep scars and burn marks. But that is as it should be. Their scars must not be erased, they are history inscribed on their flesh. Now all four figures lie on the sidewalk in ruins, Teddy awkward, bow legged, still reaching for his pistol. The figures of African and America, imperfect phantasms of western imagination, yet something that they stand for still deserves our attention.

It so happens that in the center of Moscow is a park where there is a graveyard of Soviet statues, some busts, some full-length statues of varying scales all huddled together. As one walks among them, they seem more than a little ridiculous, the wind has truly been blown out of their sails. But this is not enough. From the ruins of the old, something new must be created, another allegory.

Montage

The method I propose is montage. Filmmakers and photographers pioneered the idea cutting up reactionary old images to create radical new meanings. I am thinking of Esther Shub, one of the first filmmakers to use archival footage against itself, taking films of Czarist Russia, breaking them down into shots and then reediting them critically in The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927). In Germany John Heartfield used the same technique in his anti-fascist photomontages. The figures of the Roosevelt monument are characters in a drama that must be reimagined and restaged in a new tableau, one that both bears the scars of the old regime and invites us to imagine history differently. Inspired by Benjamin, let us, as he describe it, festively enact history.

Benjamin understood montage as political demystification. He was particularly interested in Heartfield’s photomontage German Natural History. Here we see the three stages of evolution of the Death’s Head Moth, that is also the transition from the caterpillar politicians of the Weimar Republic to the Hitler moth. The image is captioned “Metamorphosis”. This word takes on three meanings; one from nature, the stages of an insect, one from history, the transition from Hindenberg to Hitler and the last from myth, showing that just as the metamorphosis of human into animal and visa-versa belongs to myth and fairytale, so too historical progress is equally a fantasy.

Both Benjamin and Adorno thought that one should employ nature and history as dialectically opposed concepts, one critiquing the other. While the statue at the museum collapses history and nature into each other so that Teddy is presented as the pinnacle of the evolutionary chain, Heartfield’s image deliberately takes this apart showing that there is nothing natural about historical progress it is just fantasy. Society does not just evolve into something better, higher.[3]

Re-staging history

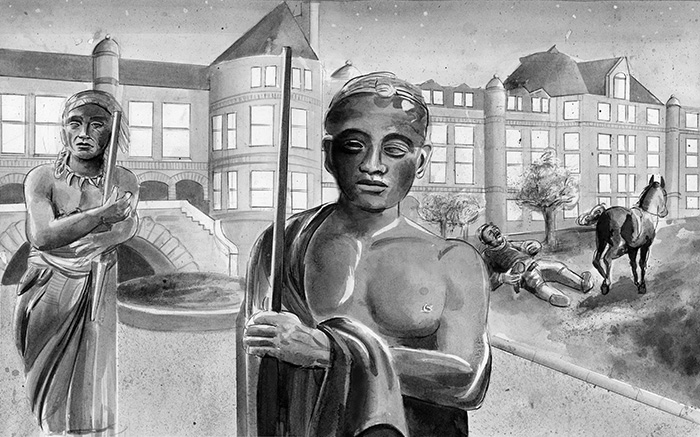

How might these elements, Teddy, Africa, America and horse be reconfigured to create an allegory for our time? The pedestal dismantled, I propose that the figures are moved from the front of the museum to the side entrance on seventy seventh street. Africa and America will be the first to greet us. Standing almost on the street, they are ready to walk out into our world, armed with spear and rifle yes, but their pensive gaze, reminds us what a difficult journey still lies ahead. It seems to me that thinking, pondering what will yet transpire is the proper attitude we must take. Action is nothing without thought. Cut out from their attachment to the rest of the statue rough scaring on their left and right sides, they bear the wounds that history has inscribed with such violence on their bodies. At the same time, these scars of separation reveal work, the work of liberation.

Some ways off, in the park that surrounds the museum, Teddy lies on the ground, as though he was thrown to the ground by his horse, who, finally free, trots away. Consigned to irrelevance, all bombast and bow-legs, Teddy looks ludicrous. This staging of a gag from a slapstick comedy is perhaps the most subversive element. Power would rather disappear from view than be made to look ridiculous. Benjamin understood very well the revolutionary power of humor in which cracks and fissures abruptly opened up in the status quo.

Zoe Beloff, The Dreamers of History, 2020, ink on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

I don’t think there is anything sacred about statues, art is just stuff, material culture that can be used for purposes good and bad. As Benjamin makes clear, monuments are all too often documents of barbarism. But he understood the power of allegory and the importance of ruins as emblem. Let us imagine a dialectical image in which this relic of imperialism is something like fossil from the past and by deliberately hastening its ruin, project the future into the present in which the figures of Black and Indigenous people welcome us to a world that is changing.

[1] Benjamin, Walter Selected Writings, Volume 4, 1938-1940 (Belknap Press Harvard, 2006) p 391

[3] For a detailed analysis of Benjamin and Adorno’s thinking on the dialectical relationship between history and nature see Buck-Morss, Susan The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts London, England) p 60

Zoe Beloff is an artist and filmmaker based in New York. Her projects often involve a range of media including films, drawings and archival documents organized around a theme.

Both thematically and formally Beloff draws timelines between past and present helping us to imagine a future against the grain of reactionary ideology. She aims to make radical art that educates, entertains, and provokes discussion. Most importantly, she believes protest should be vibrant, humorous and colorful, a carnival of resistance to light the way in dark times. Zoe’s work has been featured in international exhibitions and screenings; venues include the Whitney Museum Biennales 1997 and 2002, Site Santa Fe, the M HKA museum in Antwerp, and the Pompidou Center in Paris. She particularly enjoys working in alternative venues that are open to the community for events and conversations. These have included in New York City; The Coney Island Museum, Participant, Momenta and The James Gallery at the CUNY Graduate Center. She has been awarded fellowships from The Graham Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, The Foundation for Contemporary Arts, The Radcliffe Institute at Harvard and the New York Foundation for the Arts. She is a professor at Queens College CUNY.