Meagan Marsh Pine

Meagan Marsh Pine: Thanks for meeting Jaysen, would you mind starting off by briefly describing your practice?

Jaysen Hohlen: I am an artist, writer and curator. My artistic practice deals with housing and gay cultural geographies, particularly cruising landscapes of the past and present. A large part of a cruising present has to do with housing and digital and informational systems. The most prominent and potent example being the advent and globalization of Grindr. When I was first making this work, I was unsettled by the ways these digital platforms cut through urban geographies, such as whole neighborhoods and residential areas, to directly link private sexual spaces. I’ve also done archival research with an emphasis on pre-Stonewall, as there is relatively little didactic or concrete information on this time. Gay neighborhoods have also shifted from being a demographic that is displaced to being a catalyst for urban renewal efforts in recent decades.

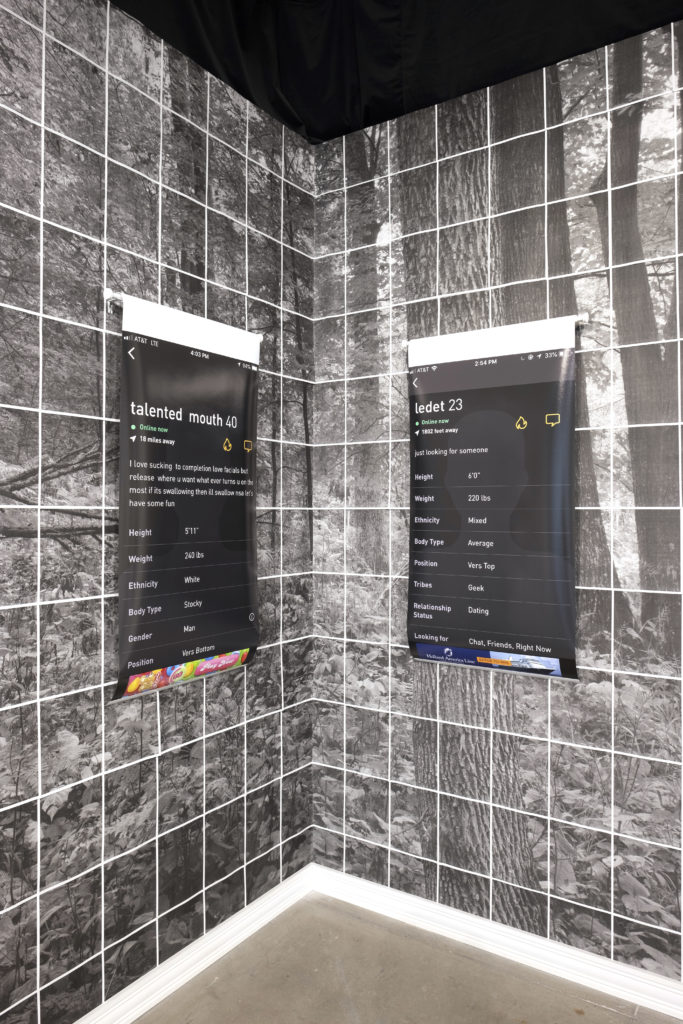

Installation View: Bounded, 2019. Katherine E. Nash Gallery. Various wheatpasted inkjet prints. Prints 50″ x 40″.

MMP: When first looking at your work, one may be struck with how you weave together images and materials from multiple sources and locations. Would you mind talking about that?

JH: My work is about multiple points of contact; institutional, historic, cultural, geographic. I want to visualize how the personal and social, public and private– shape each other. I shift between formal photographic images, archival materials, screenshots, building materials, and performance. I often let the research materialize through my process of making things. I throw a bunch of things on the wall and see what sticks. What stays is usually a good indicator for what materials are dynamic to the conversation.

Bounded Detail: talented mouth and looking for someone, 2019. Grindr screenshots archival inkjet prints, curtain rod, finishing trim, and laser prints. Prints 34″ x 24″.

MMP: Do you view your work as an exploration of identity or an act of resistance? Why or why not?

JH: There is a tendency to aim for the heroics in gay identity. The gay rights movement in the US loves to tote around a repressive hypothesis of sexuality, an orgin that traces back to a cultural understanding of the Stonewall Riots in 1969. To a degree, there is some truth to the argument, but as many queer theorists have pointed out, from Jasbir Puar to Jack Halberstam, there’s a more nefarious sexual politics at play. We have seen the mainstream gay rights movement’s version of progress in a post-Stonewall era; between military accessibility from the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, rights to sexual privacy through Lawrence and Garner v. Texas and the legalization of gay marriage through Obergefell v. Hodges. In turn, we have seen these politics be mobilized for U.S imperial expansion, as outlined in Puar’s Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times, and her more recent work The Right to Main: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Gay rights discourses are now very much a part of the barometer of a liberal state, which the U.S has used to justify their intervention, or absence of. Paur’s analysis threads this through Isreali occupation of the Palestianian West Bank, but it has since been applied elsewhere, i.e. the Netherlands and other parts of Northern Europe. Moreover, these punitive rights come at a high cost, mostly in terms of sexual and cultural homogeneity. I try to shed these grand narratives of resistance for that reason.

MMP: Is there a particular project, or thread in your work that you can point to for this?

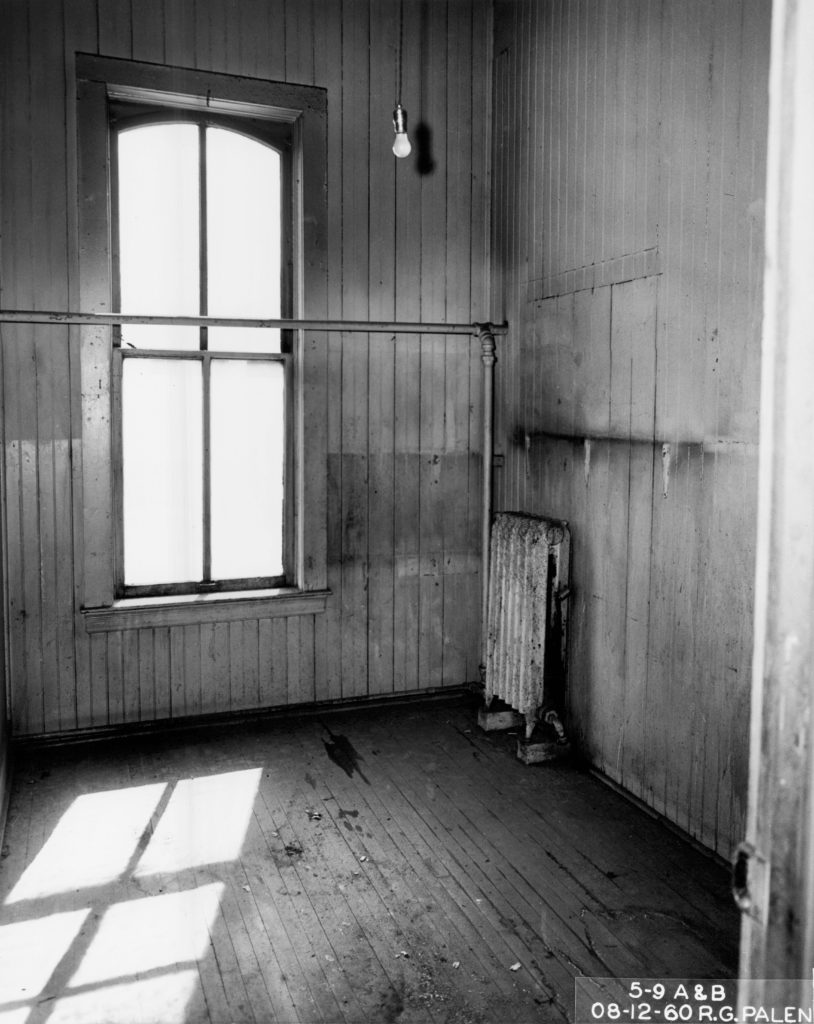

Pioneer Hotel Demolition, 1960 accessed in 2019. Archival inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the Hennepin County Library’s Special Collections.

JH: My research of the cubicle hotels in Minneapolis’ Gateway District is a good example of this. For background, the Gateway District went under federally-funded urban renewal effort in the 1950s and 1960s, which leveled over 90% of the buildings in a 22-square block of downtown Minneapolis. At the time, the district was framed as a skid-row. This was in part due to the population that inhabited the district; sex workers, Black and Indigenous people, gays, and migrant labors. I came across the district as Minneapolis’ first gay neighborhood. When I was doing archival research, I stumbled on these gorgeous images of the hotels. The cubicle hotels, also called single-occupant or tenement housing, mainly housed migrant workers beginning at the turn of 20th century. They usually worked the railroads, or in the lumber industry.

Chicken Wire Ceiling at the Pioneer Hotel, 1960 accessed in 2019. Archival inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the Hennepin County Library’s Special Collections.

I was excited because I was making these formal images of single-family homes as an aesthetic of the normative teleology of the gay rights movement, or homonormativity. In the images there were different politics of privacy and sexuality at play, or more accurately, the traces of those politics. The 8 foot by 8 foot rooms were made of plywood and had a drop ceiling of chicken wire, to preserve material cost. This also shaped the auditory layout of the room, meaning you could hear all your neighbors. The bathrooms were communal; open stalls and bathtubs. In their 50 year span, I feel safe in assuming there was at least some gay cruising taking place here. It would be lazy to use a repressive hypothesis; to make an assumption about the homophobic, or patriarchal violence that occured in these spaces, which is so often attributed to migrants and manual labors. I am sure that some violence occurred in these spaces, but there is also something that does not register with current liberal politics, something obsolete to the naked eye. These spaces proliferated different bodily and sexual politics.

The images do not speak to queer utopia of sorts, no documentation of extravagant sex parties, or signs of an exessive sexual culture. There is something more mundane about how these spaces were used. In interrogating the loud performative nature of queer resistance and revolution, Jack Halberstam talks about working toward the whimper rather the bang. The field of queer work is oversaturated with bang narrartives. It is expected and often required of us. In this way, my interest in the mundane ways people lived in these spaces could be interpreted as a form of resistance, but it is not my first impulse.

Cubicle Room Survey at the Pioneer Hotel, 1960 accessed in 2019, archival inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the Hennepin County Library’s Special Collections.

MMP: I was struck by your use of the word obsolete. Can you talk more about that in terms of your work?

JH: Of course. It is attached to Kadji Amin’s term Pre-Stonewall. Much of the LGBTQ+ rights discourses are predicated on the events of the Stonewall Riots of 1969. There has been a lot of theory that problematizes and contests the myth of progressive liberation post-Stonewall. Amin takes up the term to refer to modes of queer relations that can not be so easily folded in the homosexuality identity of the West. These modes of relations are often framed as bypassed, or obsolete, but are unassimilable to liberal myths of progress.

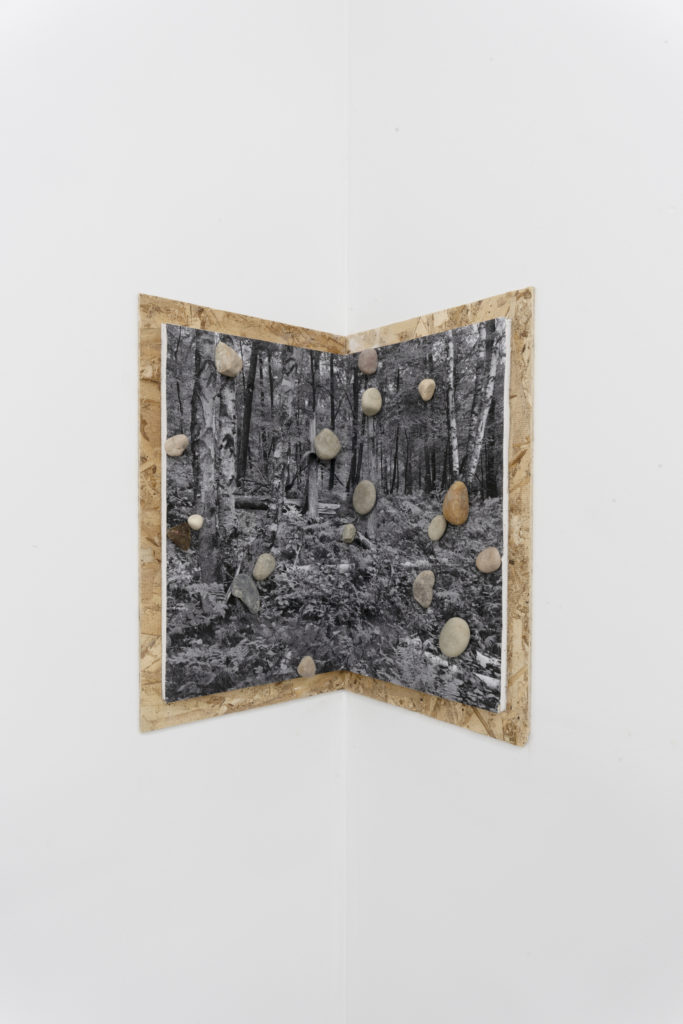

Installation View: Body Building, 2019. Second Shift Studios Curatorial Projects. Various wheatpasted inkjet prints.

MMP: In many installations (current work, Bodybuilding, and bounded), you utilize the corner space of the gallery. Could you speak to your interest in using these edges?

JH: I remember being inspired by an Anne Carson lecture on corners a few years back, and when I was working construction, I would physically make corners from wooden studs for the rooms we were building. For me, corners are diverse in meaning, both abstractly and literally. They can imply entrapment (to be cornered), forms of control (to corner the market), indicate a specific geographic place (meet me on the corner), and even communion (our corner of the world). When exhibiting, it is about an encounter or contact, literally in gallery architecture of two walls converging, but also for material and concept.

Bounded, 2019. Grindr screenshots archival inkjet prints, curtain rod, wooden trim, and laser prints. 10′ x 10′ x 5′.

MMP: I understand from your biography that you grew up in rural Minnesota and that your father’s career has been in framing houses. How has this experience impacted your work?

JH: With most fields of theory, it helps to have a foundational understanding of its labor in all forms. For me, my understanding of housing and its development has been shaped from the bottom-up. Through working with my father, constantly moving throughout my childhood and even living through the U.S housing market crash of 2008, I cultivated a fairly unique and thorough relationship to the housing market and its laborers. In terms of global narratives, real estate and development cast a large shadow both in terms of wealth inequality and housing, but also for art spaces. Real estate constitutes roughly 60% of all global assets. This estimate includes gold, bonds and equities, but the sheer magnitude of around half of global assets existing in terms of ownership of land and the construction and renovation of buildings is hard to swallow. As a curator, I try to stay vigilant to the function that art and artists play for developers, both in terms of artwashing and in collecting. Suffice to say, my father’s career has given me the vantage to see the field a bit clearer, especially its ecology from the rural to the urban.

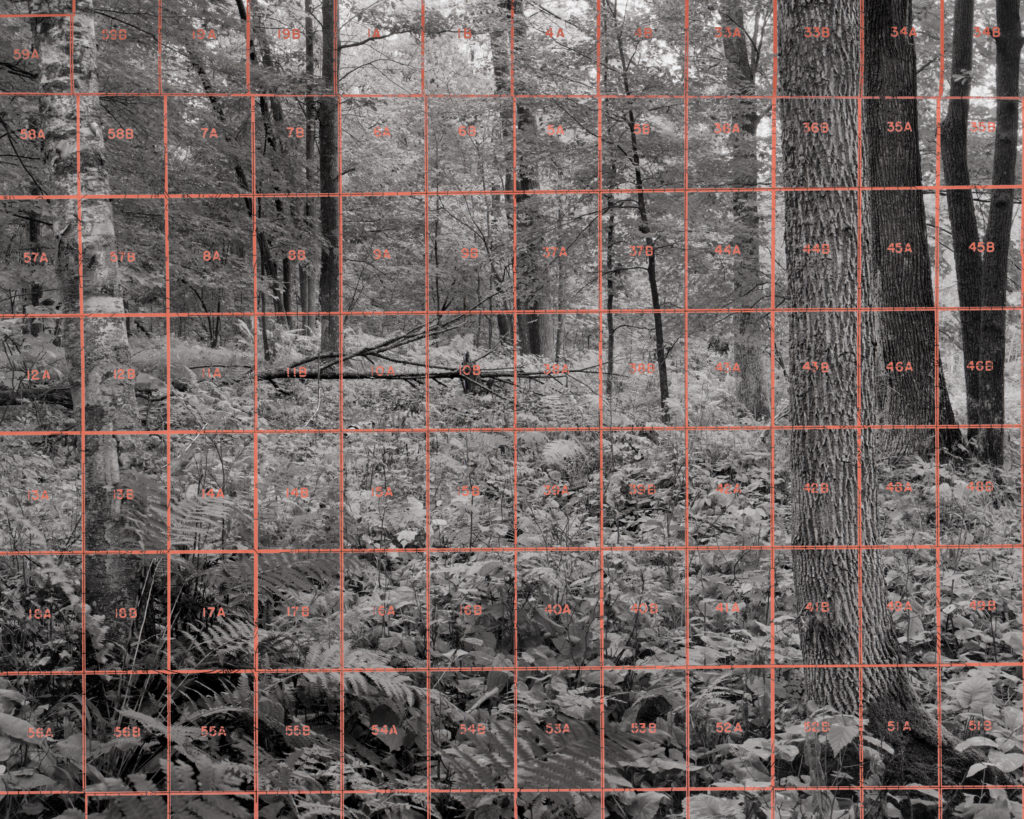

MMP: I see you revealing these ecologies in your works like Survey #3. Is there a relationship between the rural and urban you are working to uncover in relationship with the rest of your work?

Survey #3, 2019. Wheatpasted archival inkjet print. 40″ x 50″.

JH: Of course! The rural and urban are very interconnected, especially in terms of housing development. In northern Minnesota, the majority of the economy is either resource extraction (industrial agriculture, mining for precious metals, oil pipelines, lumber, etc.) or tourism. Many people in the Twin Cities own cabins in northern Minnesota. There was a huge boom in people buying, building, and renovating cabins from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. My father had one of the largest backlogs in construction projects he’s had in over a decade. In turn, we have seen an increase in the gentrification of small towns. The town neighboring my parents’ is filled with million dollar lake homes that people only use for a third of the year. The population of these towns are cut in half during the winter, so the income disparity is apparent from season to season. Much of my father’s work is also dependent on these markets. It’s this kind of double bind. As far as it relates to the urban, the aesthetics of gentrification differ greatly geographically; some are more obvious like the construction of condos that never reached complete occupancy, the demolition of buildings, or the construction of highways that bifurcate neighborhoods, others have low visibility like Minneapolis’ history of racial housing segregation through redlining, corporations buying up large swaths of land, or a new upscale coffee shop or art gallery.

PAPA, 2021, particle board, drywall, wheatpasted photograph, garden rocks. 25″ x 20″ x 20″.

MMP: You were just awarded a Minnesota State Arts Board Grant, congratulations! What are your plans for continuing your work?

JH: Yes, and thank you. Earlier this year, I wrote these fragments around my father’s career and body, fascist aesthetics and daddy kink. I was interested in how masculinity functions in both labor and gay culture. I’m seeing this as a jumping off point. I am mostly looking forward to putting my head down and making some images, and seeing what other materials manifest in the work.

Bibliography

Puar, Jasbir K. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Puar, Jasbir K. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press.

Amin, Kadji. “Anachronizing the Penitentiary, Queering the History of Sexuality.” A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, Vol 19 Issue 3: People With A.I.D.S Plaza, 2016.

Carson, Anne. “A Lecture on Corners.” Lecture, Visualizing Theory from The Graduate Center, CUNY. June 11, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYiMmCLRIQ0

Sassen, Saskia. “Investment in urban land is on the rise – we need to know who owns our cities.” The Conversation, August 6, 2017. https://theconversation.com/investment-in-urban-land-is-on-the-rise-we-need-to-know-who-owns-our-cities-63485

Kaul, Greta. “With covenants, racism was written into Minneapolis housing. The scars are still visible.” MINNPOST, February 22, 2019. https://www.minnpost.com/metro/2019/02/with-covenants-racism-was-written-into-minneapolis-housing-the-scars-are-still-visible/

Jaysen Hohlen is a Minneapolis-based artist and writer whose works engage contemporary and historic gay cruising landscapes. He graduated from the University of Minnesota with a BFA in Studio Arts in 2019. Hohlen has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, including the Minnesota State Arts Board Continuous Support for Individuals and the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council’s Next Step Fund. He has given artist talks at The University of Minnesota, Minneapolis College of Art and Design and Company Projects. Hohlen has exhibited locally and internationally at Yeah Maybe, Public Functionary and The Centre for the Periphery. He co-founded and currently runs the project space PAPA.

Hohlen grew up in rural Minnesota where his father continues to frame houses and he had his first contact with the popular gay hookup app, Grindr. These experiences, along with his interest in queer theory, continue to inform his practice. His current research explores the relationships between queer sexual cultures, displacement and development of land, and digital and informational systems.

Meagan Marsh Pine is a cross-disciplinary artist. Their work investigates how landscape images have been constructed and marketed in the West and how their representations have informed western culture and attitudes.

Meagan has exhibited nationally, including Gallery 263, Soo Visual Arts Center, and the Chase Gallery. They have been included in a number of national and local publications. They were recently featured in Witness which is housed in the Museum of Modern Art’s Library. They received their BA in art and BA in journalism from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, and are currently an MFA candidate at Washington State University.