Anisha Verghese

Colonially imposed taxonomies of gender, and sexual orientation have led to the replacement and elision of alternative ways of understanding sexuality. In the late-nineteenth century, the emerging Indian middle class—formed through the intersection of colonialism, missionary colonial Christianity, the aspiration for a democratic state and a developing capitalist economy—sought to emulate colonial ideas of modernity and respectability.[1] They, therefore, increasingly reshaped their own notions of intimacy, morality, conjugal life and gender practices to match those of their colonisers. Spurred by class dynamics and politics, the ‘middle-class,’ which comprised of upper-caste Hindus, high-born Muslims, wealthy Indian Christians, Sikhs and others, strove to distinguish their class-identity by mirroring colonial notions of sexual morality and echoed sentiments of shock and revulsion when discussing sexual deviance and the ‘immoral’ social practices of Hijra communities.[2]

The classificatory authority of the colonial matrix of power has narrowed the scope and understanding of gender. Jessica Hinchy writes of several factors that made the Hijra community an ungovernable population to the British. One such aspect was that their gender expression did not fit binary gender categories. It undermined classification and, in turn, legibility in terms of the Indian population. For instance, in the census of 1871 in colonial India, there were only two gender categories. While the colonial officials viewed Hijras as men, they self-identified as female, and therefore both ‘male’ and ‘female’ Hijras were recorded. Religious and ancient texts in Hinduism have several references to sexual ambiguity, androgyny and fluid gender roles. For instance, the composite androgynous form of the Ardhanarishvara embodies both deities Shiva and his consort Parvati or Shakti, symbolising the union of the male and female principles of Purusha and Prakriti. While queer sexualities have been accorded a place in Hinduism, it is also known to be deeply patriarchal and casteist. The current moral legitimacy and hegemony of heterosexuality is a result of the complex confluent layering of colonial encounters, historical influences, multiple religious faiths and socio-cultural factors.

Shiva Ardhanarishvara, Chola period, 11th century. Government Museum, Chennai.

Several laws in India were inherited from the colonial period. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code is one such law whose formation dates back to 1861 in British ruled India. It was modelled after England’s Buggery Act of 1533, which was the country’s first civil sodomy law. But while homosexuality was decriminalised in Britain in the 1960s, under Section 377 in India, one could be imprisoned for ten years to life and was liable to pay a fine for “unnatural offences” that were considered “against the order of nature.”[3] Part of the section essentially criminalised consensual sex between adults of the same sex. The judicial action surrounding this section of the law oscillated precariously between the High court and the Supreme Court and between support and opposition. On 6th September 2018, a proud moment for the judicial system, the Indian Supreme Court deemed part of this draconian law unconstitutional, and homosexuality was finally decriminalised.

Ironically, several religious leaders from diverse faiths with chronically irreconcilable views expressed solidarity in response to the abrogation of Section 377 and stated that it was against Indian tradition, culture, scriptures and nature itself. The violent domination of heterosexual normativity pushes nonnormative sexual minorities to the fringes of society.

This homophobic and transphobic law has often been used to harass transgenders and strip them of their rights, in particular, the Hijra community. Both historically and presently, Hijras are the most publicly visible queer community in India. They are MTF transsexuals, recognised by the Supreme Court as persons of the ‘third gender.’[4] The Hindi/Urdu word Hijra refers to a ‘hermaphrodite’ or a eunuch or intersex and transgender peoples, but this alone would constitute a reductionist translation, as there are hosts of cultural traditions associated with the community as well. Known alternatively as Hijdas, Aravanis, Kinnars, Jogappas or Thirunangais, in Hindu mythology, Lord Rama is said to have granted them the power to confer blessings on auspicious occasions, and hence their traditional occupation involves singing and dancing, usually at marriages or at the blessing of a new-born child. They receive customary gifts as well as cash for these ritual performances. Their historical and contemporary reality, however, differ radically from their traditional standing in the scriptures. Shunned, harassed, abused or disowned by their families and peers, they flee to Hijra communities in search of acceptance. The work of Tejal Shah reclaims such marginalised identities.

Born in 1979, Shah graduated with a bachelor’s degree in photography from RMIT University, Melbourne and a Master’s in Fine Arts from Bard College, NY. Their range of media includes photography, video, performance and installation. With a marked and personal interest in the LGBTQ+ community, their work is largely based on their own experiences of being queer in India. They tackle problematic assumptions of sexuality and dismantle formulaic narratives that are introduced, articulated and standardised in Indian culture through forms like cinema and art history. By employing irony, fantasy and articulating alternative desires in their work, Shah attempts to vocalise suppressed and marginalised voices.

Irony is inherently problematic to define but it is broadly understood as an incongruity between expectation and outcome or between literal and intended meaning. From the perspective of literature and linguistics, it is identified as a literary device or a trope. With the communication of verbal irony, the tone or manner of delivery, prior knowledge of the speaker’s character and the topic of discussion, might provide clues to the presence of irony. Applying irony to the phenomenological experience of the visual arts is undeniably more challenging as one cannot fall back on the conventions of a coded language to ensure its communication. Its inference therefore is just as complex.

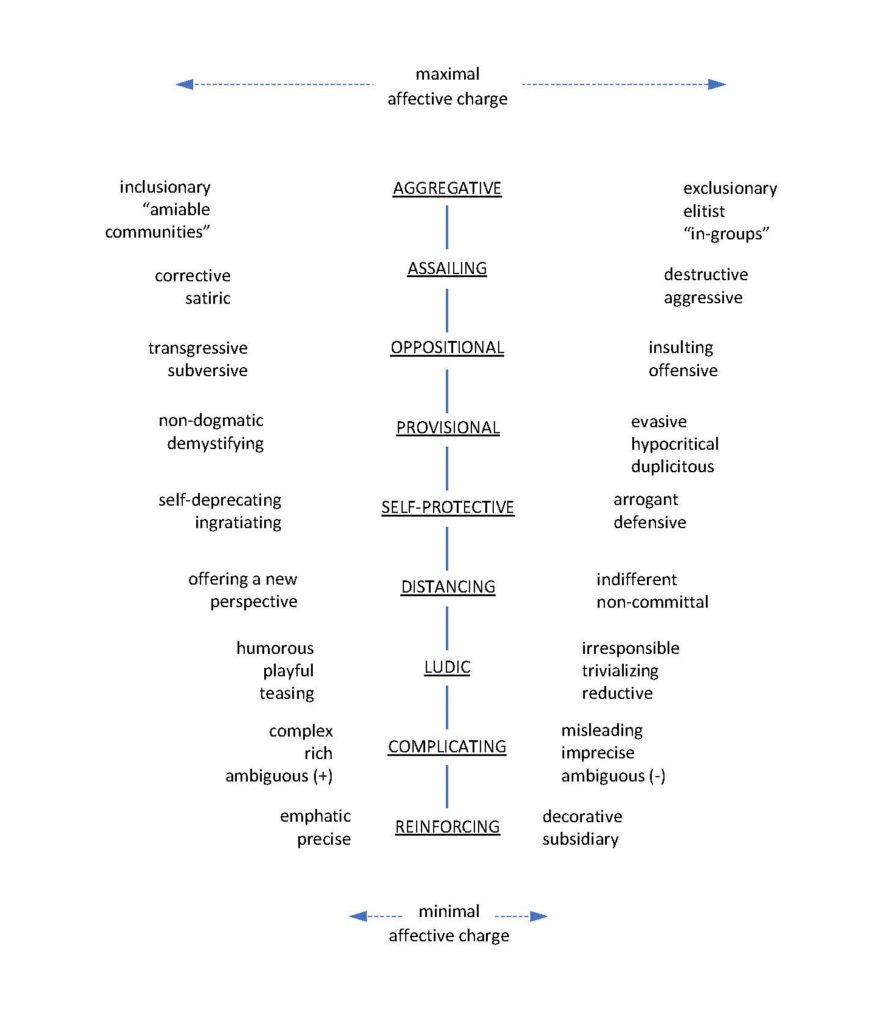

Diagrammatic table based on Linda Hutcheon’s schema of the functions of irony published in Irony’s Edge: The Theory and Politics of Irony, page 47.

As Canadian scholar Linda Hutcheon implies, interpreters of irony are not merely passive receivers of the ironist’s message. The communication of irony is also dependent on the eye of its beholder.[5] This puts us on unstable ground and suggests that the communication of irony is not always guaranteed, making it to some extent discriminatory, elitist and exclusive. Viewed in a negative sense, it can be exclusionary, limiting its performance for only those who are accustomed to it, but such an irony includes as well creating a collaboration, a community or complicity between the ironist and the interpreting audience.[6] This ‘aggregative’ function of irony, that Hutcheon identifies in her diagrammatic table of the functions of irony, could prove useful especially in the context of asymmetrically coded power for instance.[7] It could prove inclusive in its representation of a marginalised, underprivileged, disadvantaged cultural group and be used as a positive, effective tool of the minority who have been perennially excluded from the conversation.

You too can touch the moon—Yashoda with Krishna, from the Hijra Fantasy Series, Digital photograph on archival paper, 38 x 58 inches, 2006, Edition of 8 + 2 AP. Image Credit: Courtesy of the Artist and Project 88.

The Hijra Fantasy series of 2006 by Shah sheds light on culturally and chronically repressed desires; it emerged from their activist work and close association with the Hijra community of Bangalore and Mumbai. “You Too Can Touch the Moon—Yashoda with Krishna” features a transgender woman named Malini and illustrates her desire to be a mother. Displaying parodic interpictoriality, the photograph draws its reference from Hindu mythology and the popular imagery of the divine mother, Yashoda with the infant Lord Krishna. Parodying a painting from the 1890s by the celebrated artist Raja Ravi Varma, the work queers a classical image of mother and child, thus displaying the OPPOSITIONAL function of irony through its subversion. In order to establish context, let us first examine the rhetorical premise of Shah’s work and the factors surrounding its production.

Raja Ravi Varma, Yasoda with Krishna, c.1890s.

Born in 1848 to an aristocratic family, Ravi Varma learnt how to paint in the Indian tradition from a palace artist and in the oil painting technique from a visiting European artist. Known as the ‘Father of Modern Indian Art,’ he is renowned for his expertise in Western academic realism which he adapted to traditional Indian themes. His work appropriated imagery from a wide variety of sources such as photographs from theatre productions and art journals from England, Germany and France; even his knowledge of human anatomy was primarily from European prints and art books.[8] He then decontextualised the imagery by using it to illustrate classical Indian mythology, history and religious stories. Thus, the figures do not necessarily resemble the temple idols fashioned as per Hindu scriptures or their classical sculptural traditions.

Shah elaborates on their choice of the Ravi Varma painting as a rhetoric premise for the photograph:

The reason I choose Varma’s painting as a reference point of departure is because it is an uncontested fact—and an irony of history—that the problematic utopian vision infusing these paintings became emblematic of colonial India’s fraught modernity. This photo-fantasy of Malini is clearly meant to function as a perverse “queering” of Ravi Varma’s mythological pictures, and of the colonial history that produced them.[9]

Applying the ‘echoic mention’ theory of Dan Sperber and Deidre Wilson (1981) to word-based and wordless visual irony found in photography, Biljana Scott indicates that, “An echoic mention without attendant attitude qualifies as simple allusion, homage or inter-textuality rather than irony.”[10] The queering of a sanctified Indian religious painting brings about a shift in perspective; we hear its ironic tone of voice and note the irreverence and subversion in the attitudinal change.

Several taboos surrounding sexual expression and desire in India originate from colonial rule and the laws formed to enforce Victorian ideas of sexual morality. Colonial law sought to ingrain an order of succession based on patrilineal descent and procreative sexualities. The gender-diverse identity of the Hijras and their sexual practices posed a challenge to colonial efforts. Their feminine sartorial choices, asking for alms, and their animated performances in public spaces undermined colonial efforts to discipline and spatially control them. The language of ‘pollution’, ‘contamination’, ‘contagion’, ‘filth’ and ‘disease’ characterises colonial accounts of Hijras and served to stigmatise and further their social exclusion.[11]

Two dusky, earthly characters replace the divine, fair-skinned figures of Ravi Varma’s portrait—Malini masquerades as Yashoda, and the young boy plays the role of Lord Krishna. Racism and colourism (discrimination based on skin colour) was prevalent in British India, where lighter skin tones gained privilege in education and employment; and the caste system further reinforced its dissemination. Light skin is associated with privilege and high status, while dark skin is associated with socially and economically disadvantaged persons. The shot features Malini commanding the child’s attention as she points toward a moon in the background. She looks regal, bejewelled and draped in a red sari—usually considered prerogatives of the upper class—performing the ideal mother figure with ease. Yashoda is symbolic of the epitome of motherly love and affection, a role that mainstream society would vehemently deem unfit for a Hijra. Notions of motherhood are not trans-inclusive, and the biological determinism of the maternal instinct immediately proscribes its presence in a transwoman.

Incongruity or paradox are central to the concept of irony. German philosopher and literary critic Friedrich Schlegel articulates, “Irony is the form of paradox,” suggesting that it is one of irony’s defining attributes.[12] Shah evokes the paradoxical hierarchies present in the intersectionality between colour, class, caste and gender in their photograph; the ironic contrast made dramatically apparent in comparison with its rhetorical premise. The ironic juxtapositioning of Malini with the character of Yashoda, the divine mother, prompts the audience to delve into the relationship between the two seemingly incongruous elements that warrant the irony. A Hijra as a mother figure to a little boy presents itself as ironic for multiple reasons. An understanding of the cultural nuances relating to Hijra communities is essential to locating ironic intent.

The significance of the castration ritual that some sects of Hijras undergo is associated with renouncing pleasure and sexuality and achieving the elevated position of a religious ascetic. This renunciation is said to imbue them with the power to confer fertility on couples seeking to conceive, thus echoing the attributes of their patron goddess Bahuchara Mata who is the Hindu goddess of both chastity and fertility. Most hijras are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and as castration or sex reassignment surgeries are expensive, several hijras become sex workers in order to support themselves and their transformations. Although the Supreme Court has directed the government to provide equal opportunity to Hijra communities, attempts have been tokenistic and have not manifested into tangible economic and social reforms addressing access to education, employment or healthcare, property inheritance and adoption laws. The Transgender Persons Bill of 2019 provides a recent example where Courts have ignored bill amendments that trans communities have asked for and have retained transphobic actions like ‘medical certification’ to grant ‘third gender’ identity. Therefore, begging and sex work become the only available options to Hijra communities, and they are thus ironically associated with both asceticism and eroticism.

One of the pervasive colonial narratives regarding Hijras typecasts them as kidnappers of young male children and alleges that they forcibly castrated young boys and adults in order to increase their fold. Intending to reduce and eventually exterminate Hijras, the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871 facilitated this very purpose. The law painted certain tribes and entire communities as hereditary criminals based on their religion and the history of their caste occupations. Consequently, Hijras, their livelihood, bodies, economic and domestic arrangements came under great scrutiny and policing.

The illustration of Malini’s desire invalidates the colonial stereotype and subverts normative gender fundamentalism. Despite the shot visibly resembling a studio set up—with painted backdrop, carpeted ground, furniture and drapery—there seems to be a very genuine moment of the interaction between mother and son that Shah has captured, which normalises an otherwise unlikely probability of a Hijra being a mother to a boy child. How strange that the gendered identity of the flesh and body that holds love for an unparented child is considered of more import than the love itself that it stores and transmits. An interesting detail is that Yashoda is not Krishna’s biological mother as his birth parents had to give him up on account of his uncle, who planned to slaughter him based on a prophecy. This narrative of Yashodha as an adoptive mother presents itself as an underlying ironic congruence and adds yet another layer regarding the biological essentialism of motherhood, which is a patriarchal oppression on women in general but doubly affects transwomen such as Malini.

The presence of irony does not simply signal the opposite of what is being articulated but simultaneously expresses multiple sides of a tension, thus creating a dynamic space for oscillating perceptions and incompatibilities to co-exist. It is important to note, however, that through the ironic mimesis of the Ravi Varma painting, notions of class, caste privilege as well as heteronormative gender are regrettably still present. Hutcheon flags this limitation of irony and cautions that ironising authoritative discourse runs the danger of misreading, of misapprehension in the communicative space between the ironist’s intention and the interpretation of the audience.[13] Therefore, it might inadvertently serve to reify the very constructs that it seeks to subvert.

However, an audience equipped to recognise the irony of the piece might savour a deep understanding of the layers of subversion or transgression as it destabilises heteronormative univocalism. Viewed through the analytic lens of its irony, we encounter in one image the merged identities of mother, prostitute and asexual ascetic, along with the complex associations between pleasure, desire, impotence and procreation. By offering alternative perceptions to the dominant narrative, irony enables us to question not just content but also helps recognise the ability of a voice or an artistic position to generate multivocal subject positions.

Addressing similar issues of cultural, gender and sexual identity, Yuki Kihara, an interdisciplinary artist and independent curator, employs photography, performance, dance, video and installation in her artistic practice. Of Japanese and Samoan heritage, Kihara identifies as fa’afafine, which is a term that refers to a third gender in Samoan society. Kihara explains:

Fa’afafine are an Indigenous queer minority in Samoan culture known to be gifted in the spirit of more than one gender, or “third gender”; the term is also used broadly to describe those who are, in the Western context, lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, intersexed, or queer. Fa’afafine also translates as “in the manner of a woman,” and is often applied to biological males with feminine characteristics…[14]

Working from both a historical and contemporary perspective, Kihara’s work primarily destabilises the presence of an overarching Eurocentric perspective. Often inspired by Samoan postcolonial history, her body of work undermines colonial ideology and challenges standardised forms of representation of non-western peoples.

Fa’a fafine: In the Manner of a Woman, a series from 2004-5, evokes the manner of the nineteenth and early twentieth-century colonial ethnographic photography. Consisting of a series of seven photographic portraits meticulously staged in a studio environment, Kihara performs as the principal subject of these images, bringing forth for deliberation stereotyped images of Pacific Islanders and the fraught history of Western representations of the Pacific. Echoing and ironising the manner of ethnographic and commercial photography by the likes of New Zealand photographers Thomas Andrew (1855-1939), Alfred John Tattersall (1866-1951) and Alfred Henry Burton (1834-1914), Kihara mimics their exoticist, eroticist and primitivist tones through her sepia-toned images of carefully posed figures, sometimes partially nude and adorned with stereotypical cultural accessories.

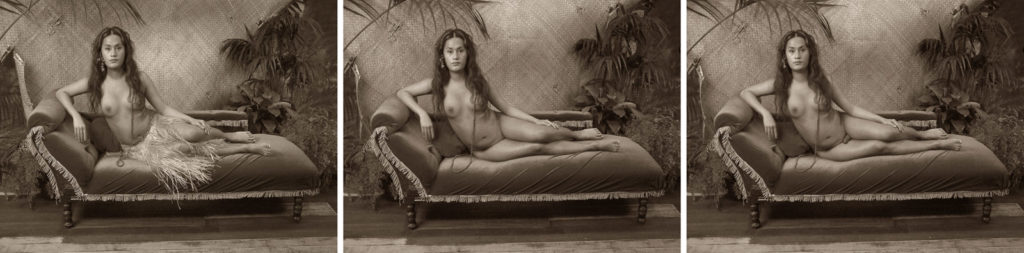

Yuki Kihara, Fa’afafine; In the Manner of a Woman (2004/05) triptych; c-print, images 600 x 800 mm each. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries Dunedin and Queenstown, Aotearoa New Zealand.

Kihara’s triptych of sepia-tinted photographs, bearing the same title as the series, uses her own body to disrupt the dusky maiden trope found in colonial portraiture as well as to challenge the Western notion of a gender binary. Re-enacting exoticised and sexualised representations of Samoan women, the first image features Kihara partially clothed in a grass skirt, bare-breasted and reclining on a plush tasselled Victorian chaise lounge, with her body fully turned towards the viewer. The ʻie toga, which is a woven mat of significant cultural value in Samoa, is positioned as a backdrop and forms a curious contrast to the Victorian furniture. Framing the scene on either side are lush tropical foliage. Kihara becomes but one more of the exotic objects she is accompanied by; her long hair is loose and cascades over her shoulder in waves while she stares directly back at her viewer.

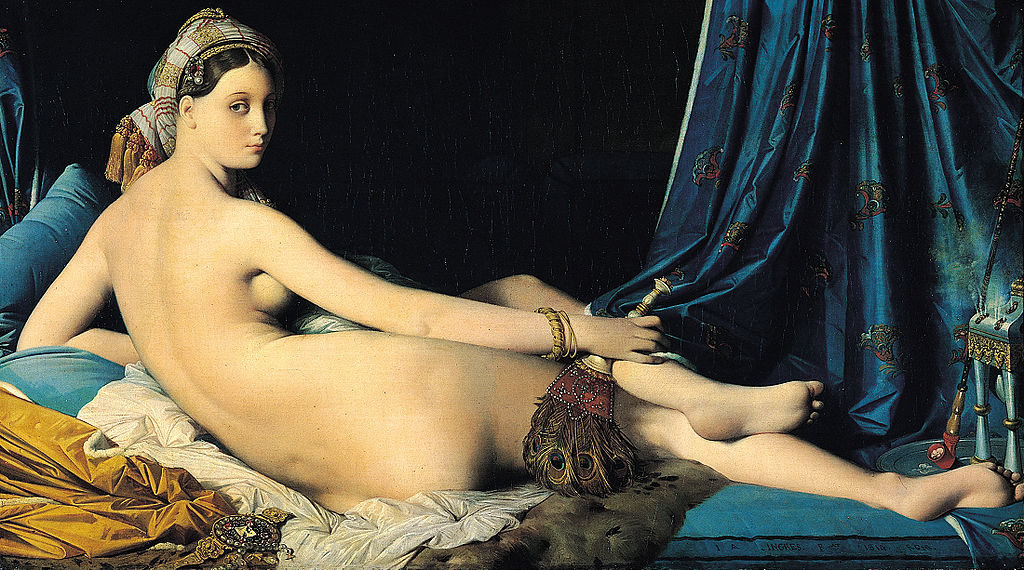

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814.

Kihara’s languid pose conjures instant associations with the art historical tradition of the reclining nude as seen in a host of European artists from Giorgione and Titian to Manet and more. A more analogous comparison, perhaps, would be the orientalised odalisques of Ingres and Delacroix that are featured alongside plush fabrics and exotic props such as a peacock feather duster. In the first image, Kihara assumes the stereotype of the dusky maiden.[15] In Kihara’s image, she explicitly performs the style and setting of ethnographic photographs where the tradition of stereotyped female sexuality is conjoined with the notion of the primitive female as unchartered territory, untouched but familiar and inviting, primed for sexual conquest. The colonised woman is doubly ‘Othered,’ with reference to both man and the European ideal.

The second image of the triptych is identical except that the grass skirt is conspicuously missing leaving Kihara completely undressed. The paradoxical connotations of the trope of ‘nakedness,’ as seen in ethnographic portraiture when compared to its presence in the ‘nude’ of Victorian art, are rich with irony. Historian Philippa Levine observes the curious inconsistencies and slippages between the ‘nudity’ of high art and ancient Greek statues and the ‘nakedness’ of the colonial native photographed without clothes.[16] While a native’s lack of clothing is equated with crude primitiveness, a ‘savage’ nature, the lack of evolutionary ‘progress’ and immoral sexual allure, the European nude of high art often symbolises innocence. The irony is conspicuous in that while the nude woman in art was once seen as the epitome of pure femininity, the semi-clad, ‘naked’ native woman corrupted through her sexuality. The aesthetic and the scientific domain, curiously free of the moral constraints that Christianity imposed, allowed the male viewer to uninhibitedly indulge his sexual desires. Through the pervasive mediums of painting and photography, fantasies were circulated as reality.

The concoction of male voyeurism and the Occidental, colonial gaze are directed towards the native female body with the arrogant assumption of its openness to Western penetration; vacuously absent, is a consideration of reciprocity. A compelling irony presents itself with the third triptych, richer still when seen in conjunction to this egotistical sexual assumption. Kihara, still positioned as the dusky maiden, reveals her penis, which was deliberately concealed in the previous image so as to make her body appear as female. The expectations of the Western colonial heterosexual male libidinous gaze are ironised. The display of not just her body but also her sex and her identity as fa’afafine in this context engenders multi-layered discussion. Her performance is not just of culturally constructed identity but is also a performative simulation of diverse gender identities. This transgresses Western binary notions of sexuality and differentiated gender roles while also parodying and disturbing the naturalisation of the dusky maiden archetype. The subversion is achieved in the OPPOSITIONAL function of irony, as Kihara both conforms to and confronts the ethnic and gender stereotype, undermining it from within.

Judith Butler, who first propounded the theory of the performativity of gender, observed that gendered identities are formed through repetitive acts or a series of performances that are naturalised over time to constitute the ‘idea’ of a woman or man. This ‘naturalisation’ establishes the foundation of the concept of an ‘original,’ which Kihara’s triptych parodies and ironises, while also highlighting the substantial part that role-playing occupies in the construction of gender identity. Butler neatly summarises the nature of parody and the concept of originality—“the parodic repetition of “the original” . . . reveals the original to be nothing other than a parody of the idea of the natural and original.”[17] Gender identity is therefore formed through a series of social and political acts that constantly shift and evolve based on a repetition of behavioural performances that become identifiable as queer, transgender, woman or man. Kihara uses the integral role-playing aspect of gender to highlight difference and subversively, to eliminate polarity.

Butler is of the opinion that “there are norms into which we are born—gendered, racial, national—that decide what kind of subject we can be, but in being those subjects, in occupying and inhabiting those norms, in incorporating and performing them, we make use of local options to rearticulate them in order to revise their power.”[18] Cultural codes typically prescribe the gender one is expected to perform. In Samoa, the influence of Christian missionaries and colonial governments altered native gender roles and relations. Crimes Ordinance 1961, an act that criminalised males ‘impersonating’ females in public spaces, demonstrates the effect of colonial laws on traditional Samoan structures of gender. The law could be used specifically to target fa’afafine.[19] While fa’afafine identify as a third gender and have specific roles in Samoan family and culture, they are often conflated with Western understandings of sexual groups and are categorised using Western sexual terminologies such as ‘transgender’ or ‘homosexual.’

In an interview with Katerina M. Teaiwa, Kihara observes with concern that fa’afafine expression is regrettably singularly and stereotypically associated with drag.[20] While noting the importance of the performative and subversive aspects of drag, which she admits is very much an important part of the fa’afafine community, Kihara wishes for people to look beyond just this one flamboyant aspect.[21] Pulling away from simplified Western assimilations of this indigenous gender identity, Kihara draws attention to Faleaitu (house of spirits) or traditional Samoan comedic theatre, where elements of cross-dressing are used to present social and political satire. The skits address issues that are usually considered cultural taboos and use parody, irony and satire to critique the dominant norms of society. Performing anthropological stereotypes, Kihara’s aesthetic drama induces alterity into the mimesis of a mimetic medium and confronts the problematic stereotype. Acknowledging the influence of faleaitu in the subversive play embodied in her series, Kihara’s performative contestation challenges not just the colonial gaze but also reified heterosexist notions of gender.

Influenced by Samoan poet and novelist Albert Wendt’s conceptualisation of the Samoan concept of ‘va’ or space, Kihara employs it not only in her practice but also draws upon it to articulate her mixed ethnic background and her identity as fa’afafine—as occupying the va between men and women. Written in the context of the relationship of va to Samoan tatau (tattoo), Wendt in his paper Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body (1996), elaborates:

Important to the Samoan view of reality is the concept of Va or Wa in Maori and Japanese. Va is the space between, the betweenness, not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together in the Unity-that-is-All, the space that is context, giving meaning to things. The meanings change as the relationships/the contexts change.[22]

While the West conceptualises space as empty, in the pan-Polynesian concept of va, space is generative. It forms associations, links and connects rather than isolates. Tongan scholars ‘Okusitino Mahina and Tēvita O Ka’ili have additionally discussed the socio-spatial relations of va. Ka’ili writes, “Va (or wa) points to a specific notion of space, namely, space between two or more points.”[23] These points could be construed as people, places or things. This is reminiscent in a way of the interactive, interstitial space between fixed identities that Homi Bhabha believes can hold difference unaccompanied by hierarchy: a space for the articulation of cultural hybridity. Wendt, however, is wary of the term ‘hybrid,’ preferring the term ‘blend’ instead, as he feels the former is entangled with the notion of purity.[24] Wendt declares that the term “‘Hybrid’ no matter how theorists, like Homi Bhabha, have tried to make it post-colonial still smacks of the racist colonial.”[25] For Wendt, va is a communal space of negotiation. Kihara perceptively notes, “I am interracial, intercultural, and intergendered. I am not a clashing point but a meeting point where all these factors meet and have a dialogue, and the artwork is an outcome of it.”[26] And with irony at play at every stage of her series, she reveals the protean and multi-faceted nature of the fa’afafine postcolonial body.

[1] Surinder S. Jodhka and Aseem Prakash, “The Indian Middle Class: Emerging Cultures of Politics and Economics,” (KAS International Reports, 2011): 45.

[2] Jessica Hinchy, Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India: The Hijra, c.1850-1900 (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 85.

[4] A landmark ruling in 2014 by the Indian Supreme Court recognised transgender peoples as the ‘third gender,’ thus acknowledging a separate legal category.

[5] Linda Hutcheon, Irony’s Edge: The Theory and Politics of Irony (London; New York: Routledge, 1994), 118.

[6] Hutcheon, Irony’s Edge, 54.

[7] In further writing, I apply Hutcheon’s functions of irony to my analysis of the artworks. I refer to Hutcheon’s table using capital letters to signify the descriptors while ‘bold’ signifies the functions on either side.

[8] Partha Mitter, “Mechanical Reproduction and the World of the Colonial Artist,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 36, no. 1–2 (February 2002): 7-8.

[9] “You Too Can Touch the Moon—Yashoda with Krishna,” Tejal Shah, Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/tejal-shah.

[10] Biljana Scott, “Picturing Irony: The Subversive Power of Photography,” Visual Communication 3, no. 1 (2004): 52.

[11] Hinchy, Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India, 46-50.

[12] Friedrich Schlegel, Lucinde and the Fragments, trans. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), 149.

[13] Hutcheon, Irony’s Edge, 14-15.

[14] Yuki Kihara, “First Impressions: Paul Gauguin,” in Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey, (Munich; London; New York: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in association with DelMonico Books/ Prestel, 2018), 170. Kihara also asserts that in her view, the term Fa’afafine developed in response to colonialism and Western methods of categorisation to differentiate those outside the status quo of the Western cisgender binary.

[15] Only to later disrupt its gendered assumption.

[16] Philippa Levine, “States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination,” Victorian Studies 50, no. 2 (Winter, 2008): 216.

[17] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), 41.

[18] Vasu Reddy and Judith Butler, “Troubling Genders, Subverting Identities: Interview with Judith Butler,” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 62 (2004): 117.

[19] The Independent State of Samoa decriminalised this law with a new legislation that came into effect on 1st May 2013.

[20] Katerina M. Teaiwa, “An Interview with Interdisciplinary Artist Shigeyuki Kihara,” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, no. 27 (November 2011), para. 6, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue27/kihara.htm.

[21] As Butler notes ironically in Bodies That Matter, “it seems, drag is a site of a certain ambivalence, one which reflects the more general situation of being implicated in the regimes of power by which one is constituted and, hence, of being implicated in the very regimes of power that one opposes.” Page 85. While drag may be used subversively to destabilise heterosexual gender norms, it could paradoxically also risk rival application in the maintenance of those very norms. Such runs the risk of an ironic medium.

[22] Albert Wendt, “Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body,” NZEPC, http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/authors/wendt/tatauing.asp.

[23] Tēvita O Ka’ili, “Tauhi Vā: Nurturing Tongan Sociospatial Ties in Maui and Beyond,” The Contemporary Pacific 17, no. 1 (2005): 89.

[24] With reference to the postcolonial body, Wendt describes it as a body that is coming into being, defining itself, amongst and in conjunction with outside influences that are absorbed and incorporated into the blend of its own image.

[25] Wendt, “Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body.”

[26] Wolf quotes Kihara in “Shigeyuki Kihara’s Fa’a Fafine,” 32.

Bibliography

Brooklyn Museum. “You Too Can Touch the Moon—Yashoda with Krishna.” Tejal Shah. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/tejal-shah.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. New York: Routledge, 1993.

—. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Hinchy, Jessica. Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India: The Hijra, c. 1850-1900. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Hutcheon, Linda. Irony’s Edge: The Theory and Politics of Irony. London; New York: Routledge, 1994.

Jodhka, Surinder S., and Aseem Prakash. “The Indian Middle Class: Emerging Cultures of Politics and Economics” (KAS International Reports, 2011).

Ka’ili, Tēvita O. “Tauhi Vā: Nurturing Tongan Sociospatial Ties in Maui and Beyond.” The Contemporary Pacific 17, no. 1 (2005): 83-114.

Kihara, Yuki. “First Impressions: Paul Gauguin.” In Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey. Munich; London; New York: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in association with DelMonico Books/ Prestel, 2018.

Levine, Philippa. “States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination.” Victorian Studies 50, no. 2 (Winter, 2008): 189-219.

Mitter, Partha. “Mechanical Reproduction and the World of the Colonial Artist.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 36, no. 1–2 (February 2002): 1–32.

Reddy, Vasu and Judith Butler. “Troubling Genders, Subverting Identities: Interview with Judith Butler.” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 62 (2004): 115–123.

Schlegel, Friedrich. Lucinde and the Fragments. Translated by Peter Firchow. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

Scott, Biljana. “Picturing Irony: The Subversive Power of Photography.” Visual Communication 3, no. 1 (2004): 31–59.

Teaiwa, Katerina M. “An Interview with Interdisciplinary Artist Shigeyuki Kihara.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, no. 27 (2011). http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue27/kihara.htm.

Wendt, Albert. “Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body.” NZEPC. Originally published in Span 42-43 (April 1996): 15-29. http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/authors/wendt/tatauing.asp.

Wolf, Erika. “Shigeyuki Kihara’s Fa’a Fafine; In a Manner of a Woman: The Photographic Theater of Cross-cultural Encounter.” Pacific Arts 10, no. S (2010): 23-33.

Anisha Verghese is in the final stages of her PhD at the University of Auckland in Art History. Her research explores global contemporary art subversions of colonial legacies and the role of irony in these critical dispositions.