Jayne Wilkinson

“You can’t send a postcard from the bottom of the sea.”

– Allan Sekula, Ship of Fools / The Dockers’ Museum

“The conditions that obtained when life had not yet emerged from the oceans have not subsequently changed a great deal for the cells of the human body, bathed by the primordial wave which continues to flow in the arteries. Our blood in fact has a chemical composition analogous to that of the sea of our origins, from which the first living cells and the first multicellular beings derived the oxygen and the other elements necessary to life. … The sea where living creatures were at one time immersed is now enclosed within their bodies.”

– Italo Calvino, Blood, Sea

ASYLUM AT SEA

The sea swallows its most determined travelers and consumes even its most assured navigators. Historically, the looming threat of injury or death during long journeys at sea was a subject with rich associations and narratives. Sea shanties and maritime myths about the bravery of seafarers attest to the dangers of navigating oceanic spaces and the fearlessness required to face the threat of disappearance at sea. Yet for so many the threats of disappearance are not poetic concerns but political ones. In the contemporary moment, such threats are all too apparent, as thousands fleeing civil war, military rule and dictatorship–in Syria and elsewhere–are faced with the decision to risk the perils of traveling by sea in the hopes of reaching more stable living conditions.[1] For centuries, the Mediterranean was a place around which populations grew rapidly, since proximity to the sea was necessary for survival: for fishing, for access to arable land, for transportation and trade and, eventually, for the expansion of empires. The waters united civilizations as much as pitting them against each other. Now a reversal has occurred, and the Mediterranean has become the most heavily militarized and surveilled sea in the world. It is not a space that unites civilizations but is the space of the contemporary border par excellence: a physically diffuse space defined not by laws per se but by a “legal regime whose precise code can be constantly reconstructed by political intent.”[2] As walled states become increasingly common, the openness of the sea and its apparent accessibility acts as a mirage, a smokescreen for a border that is almost completely impenetrable and for which one must risk their life to cross.

The images of such crossings that make their way into the media are compelling, at times shocking. In tiny boats people are crammed together, often with little in the way of supplies, navigation or safety equipment, in order to traverse a most uninhabitable space. The expansiveness of the sea’s horizon, that screen that lends itself so easily to ideals of romance and adventure is, in the current moment at least, replaced by images of the sea as dangerous, fraught and ultimately lethal. Drought, war, famine and political turmoil have, for years, been driving refugees from across the Middle East and Northern Africa into precarious vessels and out onto the Mediterranean. But this crisis was often inaccurately considered to be one of migration, and it wasn’t until recently that the language shifted towards the recognition of the dire and urgent needs of refugees in flight.

In tandem with a sharp increase in fear mongering, and the closing of borders in attempts to regulate movement and flow, the circulation of horrific images has mobilized global concern. In particular, the body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on the shore in Bodrum, Turkey, was shocking enough to catalyze corporate media to not only report on the story, but also to question the rationale for publishing such a photograph. Within the discourse of images of war and atrocity, and in the long history of photographic images that show horrors, this singular image finds its place. Debates around how images function to politicize us or elicit a compassionate response have been engaged widely for decades, because of course what is made visible to us does not always catalyze a response. Judith Butler famously articulated that it is not the image but the frame that delimits what is perceivable, and therefore what can be considered a grievable life.[3] It is through what we don’t see, in what is not visible in an image, through what is excluded by the frame, that regimes of state power are enacted. For every image of a body there are bodies unrepresented, bodies beneath, below and outside the frame, that aren’t named and cannot be grieved. In two radically different types of aesthetic projects, Hajra Waheed’s Asylum in the Sea and Forensic Oceanography’s Liquid Traces, we find artists addressing questions of migration and disappearance at sea, and the politics of visibility in the wide-open and seemingly lawless spaces of the ocean.

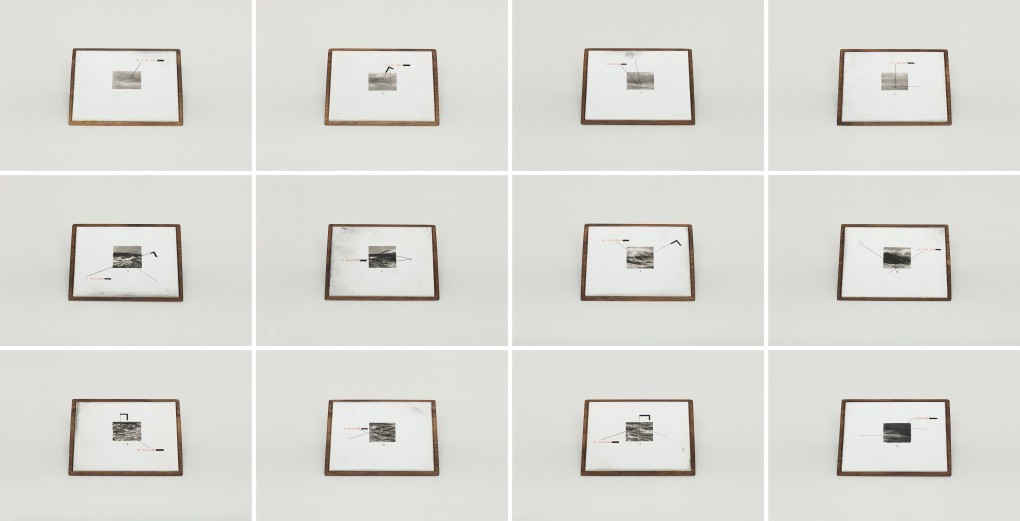

Hajra Waheed, Asylum in the Sea 1-12/24, 2015. Gouache, Graphite, Cut Photograph & Dry Transfer on Masonite & Wood. 11.4 x 14 x 6.4 cm. Photo Credit: Maxime Boisvert

DISAPPEARED, UNHEARD

The premise for Hajra Waheed’s exhibition Asylum in the Sea, presented at the Darling Foundry (Montréal) in the spring of 2015, is disappearance, in the guise of both the bodies absorbed into the sea and never seen again and the parallel dispersal of signals into the atmosphere, calls for help that never reach a receiver. The main installation consists of twenty-four small works on paper, mounted on triangular wooden frames set atop vertical supports. The front side of each of work contains monochrome fields of tiny grey dots. Resembling the visual static of old television sets, and similarly contained within a wooden frame, these mini-screens reveal no imagery, try as you might to find something within the swirling, shifting patterns of dots. They are muted screens, their abilities to send or receive image-signals interrupted by so much static. On the opposite side, only visible once the viewer has moved into and through the space, are fragments of photographs of the ocean’s surfaces, waves and clouds, collaged onto small grids. Lightly drawn onto the grids are GPS coordinates, diagrams, circles and arrows – all attempts to pinpoint specific sites in the vast, often horizonless images of the wavy surfaces of the sea. But these are futile attempts at indexing a site within an all-encompassing space. GPS coordinates give us the possibility of a location, the possibility of rescue, but the rolling, ever-changing surface of the water makes locating a fixed site impossible.

Hajra Waheed, Asylum in the Sea 1-24, 2015. Gouache, Graphite, Cut Photograph & Dry Transfer on Masonite & Wood. 11.4 x 14 x 6.4 cm. Installation View – Darling Foundry, Montreal. Photo Credit: Maxime Boisvert

Hajra Waheed, Asylum in the Sea 9/24, 2015. Gouache, Graphite, Cut Photograph & Dry Transfer on Masonite & Wood. 11.4 x 14 x 6.4 cm. Detail of Installation View – Darling Foundry, Montreal. Photo Credit: Maxime Boisvert

Reading these image collages closely, as the viewer is forced to do, creates an intimacy that is in complete opposition to the vast, repetitive surfaces of the sea. The strained intimate experience of looking for clues, of trying to decipher small marks and small images, is in contrast with the turbulent, oceanic spaces called up in the viewer’s imagination. The lost signal, the signal emitted but never received, here becomes a symbol of the unattainable. Though titled asylum in the sea, no such thing is possible. This is a world that swallows human life. It is a world whose surface is a screen–an untenable, boundless screen–that projects the allure of possibility with the simultaneous threat of disappearance.

In contrast to the historical traumas of loss at sea, the oceans are now accumulating, at alarming rates, enormous currents of plastics and refuse; they have become the twenty-first century’s dumping grounds for industrial economies around the globe. Oceanic use value has shifted, and continues to morph as the world’s oceans are increasingly networked spaces, maintaining the connectivity of global capital through the high-speed internet connections provided by underwater fibre optic cables. Despite these omnipresent uses, what Waheed’s installation poignantly reminds us of is the precarity of life at sea, for certainly the contemporary condition is one of migration and movement. She draws attention to the failures of distress signals, their inability to reach a target that could connect with the distressed subject. The beauty of these delicate, intimate installations suggest a kind of romanticization, but the poetics of representation and the consumption of beauty, myth and adventure are offset by the almost tombstone-like supports, suggesting the marking of time and a memorialization within the space that beauty fails. The works refuse a visual representation of the trauma of drowning at sea, the trauma of a capsized vessel, allowing instead the critical component of this work to be its address of visibility. The open seas may not be visually available to most people, but through contemporary communications technology, we do have the ability to map the seas in real time. It is an unfortunate irony that this ability does not necessarily implore us to help those who need it.[4] Although the Mediterranean heaves with electromagnetic signals–and many of those crossing its surface towards Europe are armed with cell phones, GPS systems, and other tracking devices–if no one is listening, the signals disappear into the ether.

DIAGRAMMING BODIES

The oceans have always been full of bodies, full of classes of people whose lives were deemed disposable by those in power.[5] Indeed, the act of disposal that the vastness of the sea allows for is what made the slave trade and the middle passage possible. Theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff argues that, contrary to Foucault’s suggestion that biopower was a modern invention, “the very need to produce and accumulate life was itself engendered in the Atlantic world by the assemblages of chattel slavery. Slavery’s modernity formed a cosmography in which the space of the living was divided from that of the dead by the sea, a place of simultaneous life and birth.”[6] So too, in current geopolitics, is the sea a space that simultaneously provides and destroys, that promises passage and a place of escape but, in its churning waves and restless surfaces, annihilates those bodies unprotected by state power.

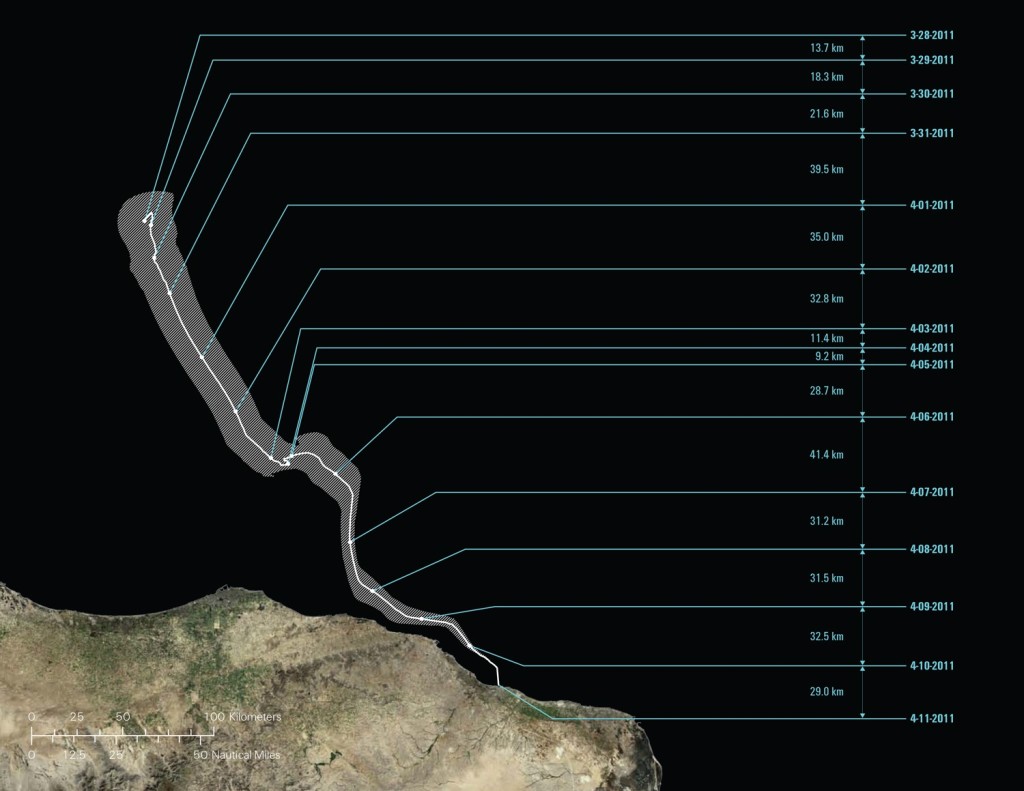

The schematic, diagrammatic video visualization Liquid Traces: The Left-to-Die Boat Case by the Forensic Oceanography research group, attempts to account for the precise details of such a potentially unknowable, unaccountable incident. The project traces the case of a boat of migrants in which sixty-three people lost their lives while drifting, for fourteen days, in the waters off the shores of Libya, and well within the NATO maritime surveillance area.[7] At the time the boat began its journey, leaving the port of Tripoli in the dark of night on March 27, 2011, Libya was in the throes of the political uprising that would eventually overthrow Col. Muammar Gaddafi and his government. NATO had just announced its military intervention. As a result of the political situation, not only were there many more attempts being made to leave Libya by boat for Europe, but the central sea had become one of the most intensely surveilled waterways in the world. By culling many forms of data–geospatial, meteorological, testimonial, military–and recombining and overlaying different data sets, the report provides a narrative of the chain of events that challenges the official story (at the time) that the NATO states did not know about the distress signal and could therefore not intervene or send aid.[8] What Hiller and Pezzano, the project’s lead researchers, were able to do as a result of the extant surveillance data, was to reclaim the space of the ocean for testimony, evidence, and ultimately justice for those who were, intentionally or otherwise, disappeared at sea. Their goal wasn’t only accountability however, but visibility, an attempt to bring attention to the systemic and ongoing deaths of refugees at sea.[9] As the refugee crisis in many regions of the Mediterranean continues to grow, the persistent work of visualizing these narratives remains critical.

From the Left-to-Die Boat Case. Drift model providing hourly positions of the vessel. The drift trajectory was reconstructed by analyzing data on winds and currents collected by buoys in the Strait of Sicily. Over time, the margin of error in the drifting vessel’s track decreases linearly as it is constrained by the known position of landing. http://www.forensic-architecture.org/case/left-die-boat/

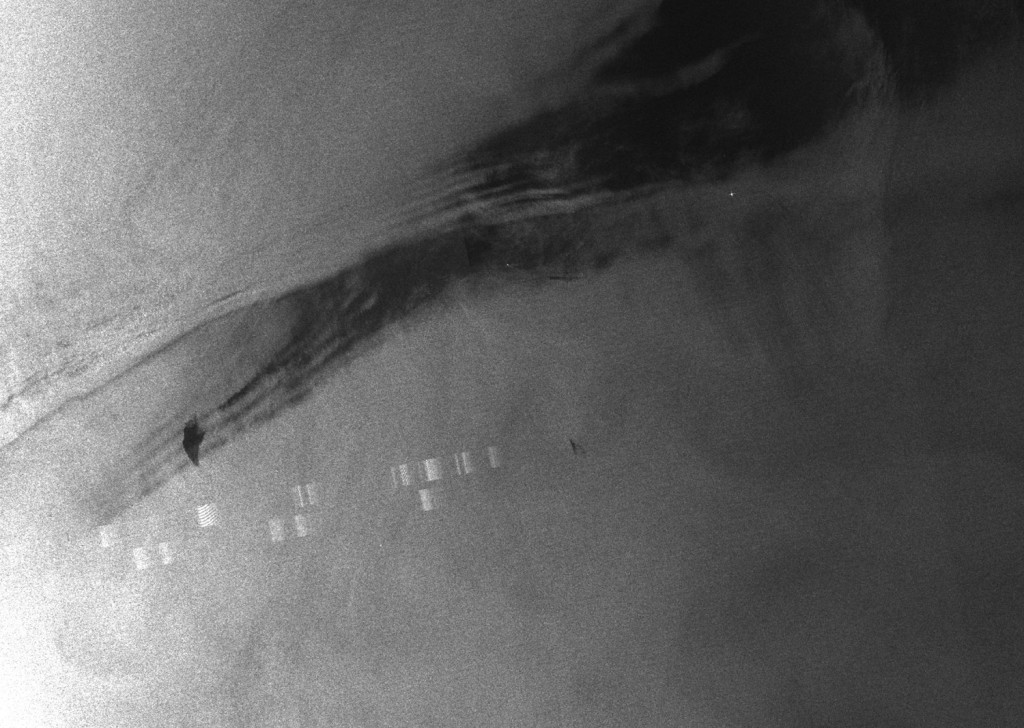

The core of Forensic Oceanography’s video lies in its use of remote sensing technology (SAR) data to determine that several very large vessels were in fact, near the location in which the boat was adrift.[10] What they term a “sensorium of data” serves to corroborate the stories of the three passengers left alive: that they were close enough to witness ships on the horizon and helicopters overhead but that, despite the technology available to military vehicles, the boat of migrants remained “unseen” and adrift on the water’s surface with no means of effective communication. What the project, as both report and video, reveals is a regime of visibility that operates to obscure rather than to make known. In their collaboration with human rights advocacy group Watch the Med, the project acknowledges that the rights to look at the sea are not universal rights. But, the rights to be visible at sea are ones civilians should have, and should not be exclusive to or contingent upon the power of military surveillance.[11]

From the Left-to-Die Boat Case. Envisat-1, March 28, 2011. Although the image reveals characteristics present on the surface of the sea – different degrees of sea roughness and currents, returns (bright pixels) indicating the presence of ships – it also shows a long band formed by regular stripes. The latter is not produced by the reflection of radar emissions from the surface of the Earth, but is a sensor-related error linked to the data transmission or to the sensor response. This distortion of the image importantly reveals the electromagnetic waves that supplement the sea’s flowing currents of water today. http://www.forensic-architecture.org/case/left-die-boat/

While the researchers undertook extensive interviews with the survivors of the atrocity, it is notable that the video itself refuses to diagram the experiences of those on board in the same way that it charts movement across the sea. Unlike the horrific images of dead or dying children and the unsanitary conditions of boat travel, here the affect of the work is maintained by its articulation of the intersections of power that operate through a refusal to see and a denial of aid. In contrast to the diagramming of bodies made to fit within the hulls of slave ships, here the infrastructure of the oppressor jettisons the body, in order to maintain national borders across a contested body of water that is only safe for some bodies, but not for all.

LOST SIGNALS

Utilizing widely divergent aesthetic strategies, Waheed’s installation and Heller and Pezzani’s case study and video project both question the politics of visibility and the precarity of life at sea. Through poetic abstraction (for Waheed) and forensic, evidentiary analysis (for Heller and Pezzani), each project articulates itself around a constellation of disappearance, displacement and lost signals; around obscurity, a lack of clarity and a directive to imagine an experience–of first traversing, then drifting, eventually being lost and drowning at sea–that is completely alien to nearly all who will encounter the works as an aesthetic experience. If art is so often about drawing on personal experience, then these works do something quite different in their demands for us to imagine spaces and experiences radically other to our own.

While their interpretive strategies vary, the projects reveal surprisingly similar concerns. Waheed’s work requires from the viewer a commitment to interpret her poetics weighed against the knowledge of an ongoing refugee crisis, an interpretation that demands the viewer become intimate with the small scale of the paper collages, with the delicate yet disturbing imagery. The Liquid Traces video and the Left-to-die Boat Case report, might appear more didactic but they too require an interpretive leap in order to contextualize the largely abstract imagery of maps, GPS locators, data points, 3D modeling and other technical imaging devices. Both projects find themselves realized through a complex mix of the index and the aesthetic, in order to both abstract an experience of the sea and to concretize it: to diagram it, to claim it, but also to suggest its lack, its invisibility. What each project articulates is a way to counter the visual regimes of control and surveillance, through civilian monitoring and intervention into such regimes.

For a disappearance at sea to occur, it means that the systems have failed, that communication signals and aid networks have broken down. The visual static on one side of Waheed’s funerary markers is the evidence that attempts were made, but failed: the paucity of information, the lost signal, the calls unanswered, each a failure. The argument that Forensic Oceanography asserts, particularly in light of the current situation of refugees crossing the seas, is the suggestion that there is a counter-politics of looking, a way “…to exercise a ‘disobedient gaze,’ one which refuses to disclose clandestine migration but seeks to unveil instead the violence of the border regime.”[12] Unveiling the violence of such regimes of visual power through an aesthetic practice that questions what is beneath the surface, what has not been made visible, is indeed the strength of both projects.

[1] http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/refugee-crisis-record-number-of-migrants-cross-mediterranean-agency-says-1.3223784. At the time of writing, more than 430,000 refugees and migrants had crossed the Mediterranean to Europe in 2015, a record number that is more than double the total for the whole of 2014, according to the International Organization for Migration.

[2] James Bridle, “Living on the Electromagnetic Border,” Creative Time Reports, November 10, 2014. http://creativetimereports.org/2014/11/10/james-bridle-electromagnetic-border-zone/

[3]Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009) xiii.

[4] There are many NGOs at work in the Mediterranean to prevent capsized boats and loss of life of refugees. Recently the organization Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) began using drones to find and get aid to boats and people in need. http://www.moas.eu/

[5]Jenna Brager “Bodies of Water,” The New Inquiry, May 12, 2015. http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/bodies-of-water/

[6] Nicholas Mirzoeff, “The Sea and the Land: Biopower and Visuality from Slavery to Katrina,” Culture, Theory & Critique 50 (2009): 290.

[7] The complete research file prepared by Forensic Oceanography, as well as a link to the Liquid Traces video, can be found at: http://www.forensic-architecture.org/case/left-die-boat/.

[8] If states can see boats in distress they are obligated to intervene, and boats flying the flag of their country would then be required to accommodate all peoples on that boat. “Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress…” United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, December 10, 1982, Article 98 (1).

[9] Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, “Forensic Oceanography: The Deadly Drift of a Migrants’ Boat in the Central Mediterranean, 2011” in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Forensic Architecture (Berlin: Sternberg Press, March 2014): 654.

[11] Ibid., 654, and www.watchthemed.net.

[12] Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, “Liquid Traces: Investigating the Deaths of Migrants at the EU’s Maritime Frontier” in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Forensic Architecture (Berlin: Sternberg Press, March 2014): 674.

Jayne Wilkinson is a Toronto-based writer and arts administrator whose research interests focus on contemporary photographic practices and the politics of visibility and obscurity in the surveillance state. She holds an M.A. in Art History and Critical Theory from the University of British Columbia (Vancouver) and is currently the director of Prefix ICA (Toronto), and the editor/publisher of Prefix Photo magazine.