Marissa Lee Benedict and David Rueter

setting the ________

Behind closed eyes, I walk across the floor. I imagine how its surface subtly changes level, gently rising here—and there, forming a shallow, worn divot underfoot. Toes, or perhaps a kneecap, might unexpectedly brush against the low, rough remains of what was once a stone wall, demarcating the perimeter of the space. Even in the projected dark, behind closed eyes, the room’s dimensions are small enough that they might be mapped quickly by random movements; or by a brief series of methodical sweeps. Bending down, my fingertips feel a latticework of shallow crevices: a million, small grooves fanning out, grid-like, in all directions. With the beating sun on my back, even the coolness of my shadofw feels eradicated as each of the flat shapes radiates the latent, insulated heat of rock. Somehow, the pitted smoothness of the surface suggests to my touch that this place, now exposed, might have been something once enclosed.

Photograph of a Roman mosaic tile floor at the ruins of Empúries (Spain). Image credit: Marissa Lee Benedict

Photograph of a Roman mosaic tile floor at the ruins of Empúries (Spain). Image credit: Marissa Lee Benedict

My eyes open. Visual access to this site suddenly advances a number of distinctions. The sea of small edges, which when underfoot held together as a single surface, becomes partitioned by acts of reading and writing, pictorial and linguistic. In English, the latticework becomes named “tiles”; in Latin, tesserae. Within this visual register, it might be noted how the floor, a Roman mosaic, would have likely been conceived as both surface pattern and structure, built as it is point by point. Warm terracotta pieces rough-in the body of the design, punctuated by white pieces that, through calculated proximities, offer up various images and referents: the airy diamond mesh at the center of the motif lies, like a throw rug, atop a field of bright white flowers with button black centers; the wildflowers dart around and under the imprecise walls of the curling and waving square border as it meanders carefully, symmetrically, with respect to the room’s rectangular dimensions—except for the fact that the entire design is offset from the back wall of the room, leaving a noticeable u-shaped ________.

As we write this description, we take note of the Roman design’s game of representation, which functions at once as an image of a thing and as the thing itself. The floor pattern, easily interpreted as a drawing of a stack of carpets, seamlessly folds and collapses exterior referents and interior space, melding hard and soft surfaces. Whether part of this same game, or the start of another, it appears the mosaic’s anonymous author placed a clear conceptual distinction between the central pictorial space and the space of that ________, which—now that the floor is empty—weighs down the margins like an overly large header or footer on a page of stone. Looking more closely at the ________, the petals of the wildflower motif noticeably dissolve into its ground, passing under the meandros to transfigure into white noise, or a drift of snowy, fine lint, settling, quietly, under a bed.

We first encountered the mosaic while wandering the exposed, dry clifftops of the ruins of Empúries, a Greek port city with a later Roman addition located in what is now the northern, interior coast of the Catalonia region of Spain. We were told, through musical interludes and a trained voice with a slight British accent, that this kind of ________ is common to domestic Roman tile work across the former empire. Inlaid floors of this kind were at once narrative and functional, employing pictorial space, as well as its absence, to stage the occupation, placement, and orientation of a room’s inhabitants, the direction of their gaze, and the position of their furniture (the mobile elements of the room, translating from mobilis in Latin, or muebles in Spanish, as literally “moveables”). The floor holds a grammar of social and conceptual function that is often found in technical forms of inscription: inscription that directs itself towards certain specifications or outputs; inscription that expands and crawls through spatial and temporal languages to transpose, guide, direct, manage, and dictate the form and disposition of the objects, forces, materials, social patterns, architectures, or disciplines to which it is turned; inscription that functions as a visual program. As stone drawing and foundation, the mosaic floor at once pictures and enacts a linguistic choreography as a domestic architectural program written at 1:1 scale on the very floor it programs. The voids of such inscriptions can be as descriptive as the imagistic spaces, in that acting along more singular vectors (such as dimension or orientation), such spaces describe their own standards, conditions, or parameters. The ________ness of the mosaic floor, then, might be read as describing its own psychological dimensions, self-narrating its prevalent desires for undergirding, receding, and maintaining its own sub-visibility.

Trudging up the steep grade of concrete I am losing moisture fast. It’s too dry for sweat to accumulate, or even bead—let alone drip—down my back or lip. The hills of San Marcos, California, are a golden Mediterranean hue, with the dry grasses of their chaparral oddly perforated at regular intervals by green blazes of manicured lawn. My body is awkward here—an odd, walking figure silhouetted against a sea of concrete ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s. Cars glide smoothly past on the compacted, heat-soaked asphalt. They violently, yet mercifully, provide a momentary wall of breeze that is accompanied by a wave of sound that rips through the otherwise still air. Opaque gazes emanate from behind shade-darkened windows. The traffic lights change and I cross the river of pavement to scramble up a vertical embankment of loose granite rocks and heavy sandy earth that rims the gutted hillside. The embankment overlooks an expanse of carved squares. The slope is undergoing a leveling—a forced scraping and pushing necessary to accept the future army of standardized housing units that will follow. These ________s, or ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s, as they are at once what is being templated and what will remain residual from this process of templating, appear as if drafted across a sheet of vellum by one of those thin, flexible, steel architectural stencils; drafted and then violently pressed and stretched (the temp- in “template”), or cut (tem-), into the land. To someone who has never seen these ________ or ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s before, they might all look the same. And for the most part they are. Yet, within the sameness of this technical surfacing, this violent preparation of the ground, subtle distinctions can be read in the soil itself as it resists, crumbles, and falls away from the voids being inscribed upon it—minor variations on sedimented compositions of temporal chance.

I am reminded by these ________ and ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s of an array of motel carpet samples laid out for months by my father in the garage of our rental house sometime between the years 1993 and 1997. From what I can remember, he was contracted by Motel 6, a budget hotel chain somewhere in the Orange County region, to source the best, most cost-effective, stain-hiding, flame-resistant carpet for a major renovation and remodel of the property. In my memory, these carpet ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s possessed a vital key to our family’s sustained economic well being, and thus were to be carefully observed. Personally taking it upon himself to test the advertised qualities and technical claims of each carpet sample he acquired, I see my father, illuminated by a wash of southwestern yellow sunlight through the crack of a partially lifted garage door, surrounded by curls of smoke from cigarettes that he is putting out, one by one, crushing them into the carpet ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s. Examining these burns late into the evening, attended by the incessant flickering of moth wings under the overhead fluorescent lights, he would record the scarred differences left by each burn mark, searching through the melted and charred fibers to find those that erased themselves best within the packed low-relief of the looped or woven plastic piles.

Figured as a massive accumulation of institutional and spatial programs, the world of built and unbuilt things can be read as the yield of a series of templates, templates which inevitably fade into the background while persisting in their effects. Templates draw out, cut into, cordon off, extrude, shape, mold, or push through, coalescing matter into form. A template, as a technology, implies a rewriting, and emptying, of what will be pushed through it, projecting, Janus-like, a ________ness both backwards and forwards. Behind is the ________ness of “raw” materials, forms, and concepts; and forward, post-processing, is an embedded ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻ness of disambiguation, parameterization, or standardization for circulation and consumption. Doubling down on a logic of normalization, any irregularities inherent to the “raw” material were never meaningful, and if they were, they are no longer.

Such template logics pattern the landscape of North America. Flying across the western United States, the sea of frozen ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻s stretching across the land look like tesserae in some enormous, inlaid mosaic floor. Calculated and divided according to the Public Land Survey System (PLSS), or Rectangular Survey System, these ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻s have been processing “formlesness,” into “form” for over two hundred years, beginning with the official decree of the US Land Ordinance of 1785. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, the newly created US federal government ________ed, claimed, and processed, through the world’s first nationwide cadastral survey, the lands inhabited by indigenous peoples into own-able, occupiable, and forcefully defended bundles and parcels, standardized in 6×6 grids within one-square-mile sections, inscribed and mobilized through codified standards and templates in service of urbanization, settlement of war debt, and westward expansion.

A century and a half before the PLSS, British colonial frameworks of property pressed themselves, overtly, as a choreography of ________ness, into this land. Early colonists including John Winthrop[1] appealed to ancient legal precedent for British claims to ownership of New World lands, employing the Roman legal concepts of res nullius, dominium, and vacuum domicilium in arguing that the absence of permanent agricultural settlements, plantations, or colonies meant that land was claimable by whomever “improved” it or, as John Locke later described the territory, the “vacant place of America.”[2] Writing as English colonization accelerated in the late 17th century, Locke refines Winthrop’s defense of raw appropriation into a theory of labor and foundation of civic virtue, arguing that the “wild woods and uncultivated waste of America, left to nature” can be fed into the template pattern of a Devonshire farm, which through private enclosure and management can in fact increase the “common stock of mankind,” perhaps by a factor of “a hundred to one.”[3] Unlike the British liberal order, this appropriated world would be built from the ground up, not from the shards of monarchy or any pre-existing culture, but from an influx of settler households in an ever-expanding matrix of private squares of fenced property, projected into the future as a new kind of civil society. Centuries later, Robert Smithson would walk through the suburbs of Passaic, New Jersey, describing and recording encounters with the persistent afterimage of these template logics, these legal frameworks of ________ness. He writes “Passaic seems full of “holes”… and those holes in a sense are the monumental vacancies that define, without trying, the memory-traces of an abandoned set of futures…” Near the end of the piece he cryptically asks: “Has Passaic replaced Rome as The Eternal City?”[4]

touching the ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎

Grasped tightly in a fist, we imagine the small lump of metal warming quickly in the clutched darkness of an enclosed palm. Without looking at it, but slightly cracking open fingers to turn the object round and round, over and back, the tiny lump offers to the touch a varying series of contours: smooth rolling edges wrap around the pebble-like form; on one side, fingertips might catch on, or a pinky might press into, indents like deep geometric furrows; the other side feels covered with slightly textured bumps, suggesting an ultra-low relief pressed or etched into the object, the highs and lows too far apart and irregular to be text.

Opening our imagined hand, and bringing the object up to our eye, we see it is a coin, but one that is resolutely pre-modern. The malleable look and feel of the metal suggests it is precious. Dug up in the region that is now modern-day Turkey, the lump is a Lydian Stater, circa 500-650 BCE. Formed most often with a lion and bull motif on one side, and a single or double ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎ on the other, Lydian coins are to date the earliest known examples of a standardized, government-issued currency, authorized by a king. The strangely modern geometric marks, on what numismatists call the “reverse” side, are left by the die used to strike the coin’s form, and speak to an evidentiary memory specific to metal—with its material structure that remembers where it has been cut, bent, or broken, right up until it is melted and recast to form a new, pristine ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎. Opposite the relief of the kingdom’s symbols, these “incuse squares” record the physical act of pressing raw material, through a template, into the realm of the semiotic.

Photograph of a Lydian Stater, minted circa 500 BCE, photo courtesy of the Classical Numismatic Group, Inc, https://www.cngcoins.com/

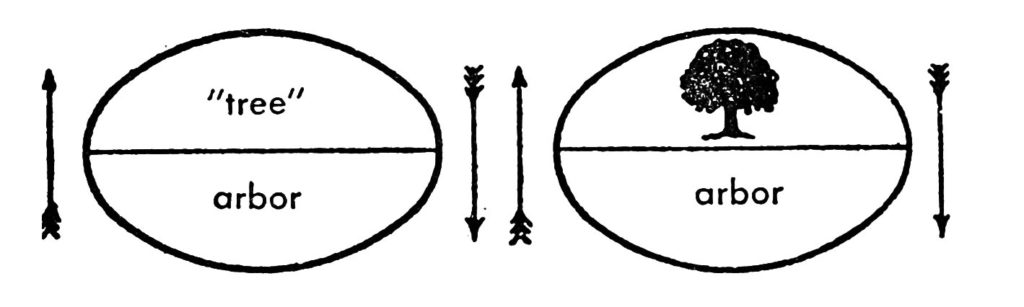

In his effort to “prove that language is only a system of pure values”, isolated from the realm of the tangible and material, Ferdinand de Saussure enlists a metaphor relating to coinage. After summoning a peculiar image of “the air in contact with a sheet of water” as a way of imagining the two-sided relation of sound to thought, he moves on to another metaphor for the value of words in distinction from their materiality:

In addition, it is impossible for sound alone, a material element, to belong to language. It is only a secondary thing, substance to be put to use. All our conventional values have the characteristic of not being confused with the tangible element which supports them. For instance, it is not the metal in a piece of money that fixes its value. A coin nominally worth five francs may contain less than half its worth of silver. Its value will vary according to the amount stamped upon it and according to its use inside or outside a political boundary. This is even more true of the linguistic signifier, which is not phonic but incorporeal—constituted not by its material substance but by the differences that separate its sound-image from all others.[5]

Such a (mostly) pure symbolic relation could be said to hold for the silver five-franc coin, but this was not always the case for the currencies that preceded it. Later studies on Lydian and other early currencies suggest that the materiality of coinage was an essential feature of its value (understood both as semantic role and value as currency), which fueled what would become a “military-coinage-slavery complex.”[6] In this telling, coins were originally used to assemble and pay armies for the purpose of foreign conquest, which yielded bullion for minting more coins, as well as well as the ability to enslave foreigners and put them to work mining additional quantities of precious metals. Such a complex semio-material system, uniting symbol with the practice of violence as an organizing principle of society, points in a very different direction than where Saussure wants to aim. Purity, in either the moral or the intangible sense of the term, can only be claimed through a ________ing of this history of coin metal. Projecting this ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎ing forward is also necessary for this claim of symbolic purity. Saussure himself admits that currency’s value varies not just according to arbitrary denomination, but also “according to its use inside or outside a political boundary,” which can be nothing other than the innumerable concrete ways that money organizes the essential matters of life and death in French society and beyond. This aspect of the coin’s value does not reappear in his analysis of language.

Excerpted diagram from Course in General Linguistics (1916), Ferdinand de Saussure

In this way Saussure’s semiology, which subtends late 20th-century notions of the self-reflexivity of language, and whose imprint can be found in much contemporary art and art theory, as well as in language-based artificial intelligence, can be approached through a critique of the projection of ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎ness. Through Saussure’s conspicuous exclusion of concerns relating to reference and referent in what he calls the material world, as opposed to the realm of the purely symbolic — concerns that bring in the situated and specific ways in which people and institutions use words to coordinate everyday life, as well as the ways that concepts and languages evolve through exercise in the world—a curious picture emerges of a language without a world, material culture, or even people. In this rarefied space, “nobody uses language; on the contrary, language uses and responds to itself. ‘Our’ bodies appear, but only as part of the general ‘web of signs’”[7]. A similar ________ing and ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎ing of words flows into contemporary linguistic research in machine learning, which has made it possible to quantify the precise value, in the Saussurean sense, of every word (in any language) within a framework of 300 emergent dimensions. From this vantage point words like “body,” “energy,” “metal,” and “violence” register as fungible tokens in a web of pure relation, always ready to be exchanged and revalued by the agents of a digital marketplace.

There are, of course, other ways to think, speak, write, and build than through the logic of the template. Signification could be thought of as a touch—a footstep, a caress, a wounding blow—emanating from love, fear, hatred, curiosity, greed, or any other human situation, an imprint of thought and action, on something shared, emerging through iterations of encounters with others. The touch perturbs, it relates itself to past touches both similar and different, as it continues or upsets a tradition. There is no use for emptiness in this idea. Nothing must be ________ before it can be touched, nothing must be presumed identical to anything else, as each touch continually transforms life in an ongoing cycle.

A thousand and some years after the Roman floor of Empúries was laid, the demarcated ________s and ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s are expanded to horizons of the past and future, across architectures and objects, and through language based technologies such as artificial intelligence and the blockchain. For some, the ________ are seen as an expression of a universal logic of function; of a simplicity of form that can circulate without reference to context or specificity; a universal language of reason and progress and production of knowledge; a rationalism and liberalism projected by free speech, free markets, and the imperial projects of democracy. The discourse of the ________ does not want to see its parameters as parameters, but rather as the conditions of freedom. These projections of the ________ desire to host, while at the same time foreclosing on ambiguities, as they are only able to speak within a certain, unambiguous, highly specified register. The movement between projecting the ________ and filling the ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎s is a vacuum that desires to draw everything into this register.

What tensions can we find in the conditions frozen by and into this ◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻ness? Descriptive languages—visual, oral, or strangely written—that remain foreign to the logic of the ________, can open it, within the space of an encounter, to becoming something else. Something other than the substrate of an intended use; something that cracks according to unknown built-in contours; or perhaps something that refuses its purpose and stubbornly maintains its “pre-form” nature, even as its environment seems to demand its adaptation. There is a terrain to which things are bound, and this is not the horizon of possibility, but the well from which the human energy of potential can spring. Not in the rupture or decisive action of an arbitrary imprint, but from tracing and cultivating and molding received forms.

[1] Winthrop, John. “Winthrop Family Papers.” Papers of the Winthrop Family – Massachusetts Historical Society, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.masshist.org/publications/winthrop/index.php/view/PWF02d080.

[2] Anthony Pagden. Lords Of All Worlds: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France c. 1500-c. 1800. Yale University Press, 1995.

[3] John Locke. “The Project Gutenberg eBook of Second Treatise of Government,” April 22, 2003 [eBook #7370], https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7370/7370-h/7370-h.htm

[4] Robert Smithson. “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey,” 1967, https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/tour-monuments-passaic-new-jersey.

[5] Ferdinand de Saussure et al. Course in General Linguistics. Columbia University Press, 2011.

[6] David Graeber. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Random House Inc, 2012.

[7] Toril Moi. Revolution of the Ordinary: Literary Studies after Wittgenstein, Austin, and Cavell. The University Of Chicago Press, 2017.

Marissa Lee Benedict and David Rueter’s site-adapted videos, sculptures, and drawings intercept objects and processes that extend beyond one’s peripheral vision. Often working with architectural or infrastructural elements hidden in plain sight, the duo lodges materiality, voice, intimacy, and at times their own bodies, into the heart of abstract and technologically-produced spaces, where such things seem legible only as objects. Troubling contemporary vocabularies of scale, representation, and abstraction with historical specificities, Benedict and Rueter pace into and out of exhibition sites, dragging with them fiber optic cables, misused industrial water bottle preforms, abjected modernist diagrams, and pieces of salvaged flooring. In its circulation, their work accumulates and adjusts as it encounters institutional logics, frictional proximities, hearsay, and fragments of collective imagination. Benedict and Rueter live and work between the United States and Amsterdam, Netherlands.