Jennifer Rabin

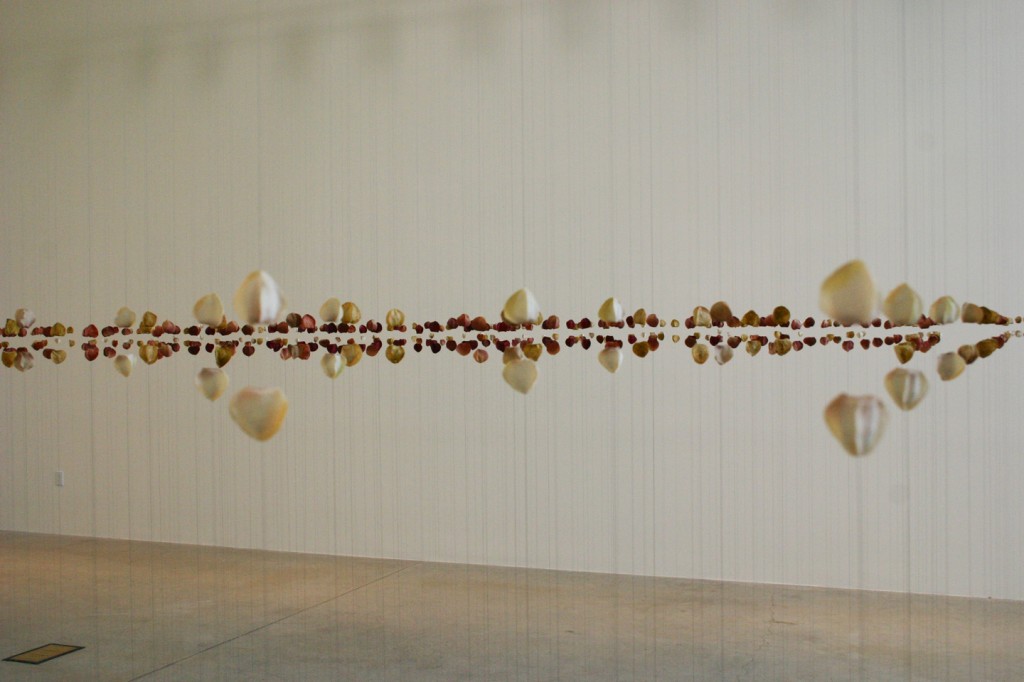

Crystal Schenk, Artifacts of Memory, 2012. Magnets, wire, silk flower petals. All images courtesy of Cris Moss.

Walking into the Linfield Gallery, where Crystal Schenk’s Artifacts of Memory is installed, is a disorienting experience. It is difficult to make sense of what you are seeing. At first, the eye is drawn across the gallery by two horizontal lines of pod-like structures—the top row hung from the ceiling and the bottom row suspended above the floor with near-invisible wire. As you let your eyes adjust, you realize that what appeared to be a two-dimensional line of pods is in fact a three-dimensional haze that fills the gallery.

Schenk, an American sculptor and installation artist, lost her mother to suicide in 2004. She made Artifacts to represent the overwhelming grief she experienced in the wake of her mother’s death. For an artist, there is perhaps no greater challenge than to embody an emotion, to give voice to the ineffable, to bring form to the formless. With Artifacts, Schenk accomplishes this in a number of ways.

In the beginning, grief is sharp, savage, violent. The pods start red at the center, like a wound, and are tightly arranged, unnavigable. If you follow them outward toward the edges of the installation, they become sporadic, fading to pinkish orange and then to white, drained of their lifeblood. Anyone who has experienced a profound loss knows that grief is not linear, that it can feel more like a cloud of heartbreak through which you can move in any direction, backward or forward, up or down, often not knowing where you are headed or where you have been.

Each pod conceals a magnet, which generates an attraction between it and the pod above or below, holding them together. The magnetic field is another nonlinear force, so it is appropriate that the artist chose this as the organizing principle for the work. Were you to hold your hand between a pair of pods, the magnetic field would pass around it, undisturbed, just as pain and grief can dodge anything you put in front of them, always to come back around. It is interesting to note that although the magnets are powerful, there is a tenuous connection between them. According to Schenk, if the pods were positioned any closer together, the magnets would snap together, ripping the wires from the ground where they are tethered. Any farther apart, and the wires would fall slack without enough force to hold them up.

This is one of many references to memory. In conceiving this work, which was first exhibited on a smaller scale for Schenk’s graduate thesis in 2007, the artist studied neuroscience to learn how memories are processed and stored. She wanted to understand how a memory, which once felt so urgent, so immediate, could later recede to the edge of her recollection, how a connection that was strong enough to rip her from her tether could later fall slack in her mind. In this way, Artifacts is a reflection of how both grief and memory are transformed by time.

Aesthetically, there is a nod to the work of British artist Cornelia Parker. In her installation Mass (Colder Darker Matter) (1997), Parker takes the charred remnants of a church that was struck by lightning and suspends them from the ceiling of the gallery, the larger pieces hanging densely at the center, splinters hovering toward the edges as if in mid explosion. In Subconscious of a Monument (2005), chunks of desiccated clay excavated from underneath the Tower of Pisa dangle from wire inches above the floor, creating a stratum that is equal parts matter and air.

Parker and Schenk play with space in a similar way, but while Parker’s work centers on the material, Artifacts deals in the intangible. If Parker translates the physical into the emotional, Schenk does the opposite.

Crystal Schenk, Artifacts of Memory (detail), 2012. Magnets, wire, silk flower petals.

By exploring the intersection of nature, science, and art, Schenk creates a phenomenological experience that transcends all three. The pods, made from silk flower petals, acknowledge the natural world. It is easy to imagine that one day they will crack open, as seedpods do in nature, to release their contents, and from death will come new life.

Shift your focus to the space between each pair of pods and you will discover how the artist marries science and wonder. The gap is an allusion to the synaptic cleft between neurons in the brain where impulses of love, joy, fear, and loss are communicated, where memories are made. The viewer isn’t meant to make this connection; it is esoteric information, a product of Schenk’s research that provides another layer of subtext for the work. What the viewer can perceive, however, is the feeling created by almost two inches of negative space that goes back into infinity. Schenk hung all of the pods so that the gap falls precisely at her eye height, a subtle way she references her own body and brings herself into the work. Only by standing at her eye line, in her metaphorical shoes, can we stare down into the vast plane of nothingness. Doing so elicits a visceral reaction—the brain and the body have no way to contextualize such emptiness—and this is where the work comes to life in a way that defies explanation.

It is worthwhile to view the installation from multiple vantage points. Crouch down, and you loose the plane of empty space. There is only a mass of pods above you, like raindrops in suspended animation about to fall. Climb onto the wooden step that the artist has put against the wall for this purpose, and you feel like a passenger in a plane that has finally broken through the clouds to where the sun is shining. The heaviness that felt so inescapable on the ground is now beneath you, behind you, a memory.

The installation is hung in the shape of a boat, an allusion to Charon, the ferryman from Greek mythology who brought souls across the river Styx into the afterlife. It was his vessel that took the artist’s mother beyond the world of the living and into the hazy realm of memory, and which transports the viewer of Artifacts of Memory to the other side of grief.

There is an overwhelming desire to enter into the installation, to slalom the wires, to run your hands through the empty space between pods, to be engulfed. But we are kept at a distance. We can walk around the piece, we can see the boundaries of it, but we cannot get inside. The artist shares her grief with us, but keeps us on its periphery, allowing us the space to contemplate our own relationship to grief, which would be impossible were we fully immersed in her experience. In this way, Schenk achieves true communion with her viewer, a chance to marvel at our shared humanity.

Crystal Schenk, Artifacts of Memory, 2012. Magnets, wire, silk flower petals.

Artifacts of Memory, is on display at Linfield Gallery, McMinnville, Oregon from April 2 – May 5, 2012.

Jennifer Rabin received her MFA in creative writing in 2008 and has recently finished her first book, Places They Have Never Been, a memoir about a long-distance marriage. Her work has appeared in Harvard Review, Nerve, Bitch, and The Rumpus. Currently a student of sculpture, she is delighted to be able to combine her two loves by writing about art. She lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and their mutt.

www.jenniferrabin.com

Crystal Schenk primarily makes sculpture and sculptural installations, which address issues of physical and mental health/illness, memory, heritage, and social constructs. Much of her subject matter is drawn from her family history. She has a labor-intensive and detail-oriented way of working, in which craftsmanship and material choices play a large role. In 2006, she received the International Sculpture Center’s Outstanding Student Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award. Her work has been published in Sculpture and Craft: magazines and was exhibited in the Oregon based biennial, Portland2010. Schenk is represented by art-st-urban in Switzerland, which awarded her with the institution’s first Emerging Sculptor Award in 2009. She recently gave a TEDx talk at Concordia University and is currently working on a public commission for Division Street in Portland, Oregon with her frequent collaborator Shelby Davis.

Crystal has a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (99′) and an MFA from Portland State University (2007). www.crystalschenk.com